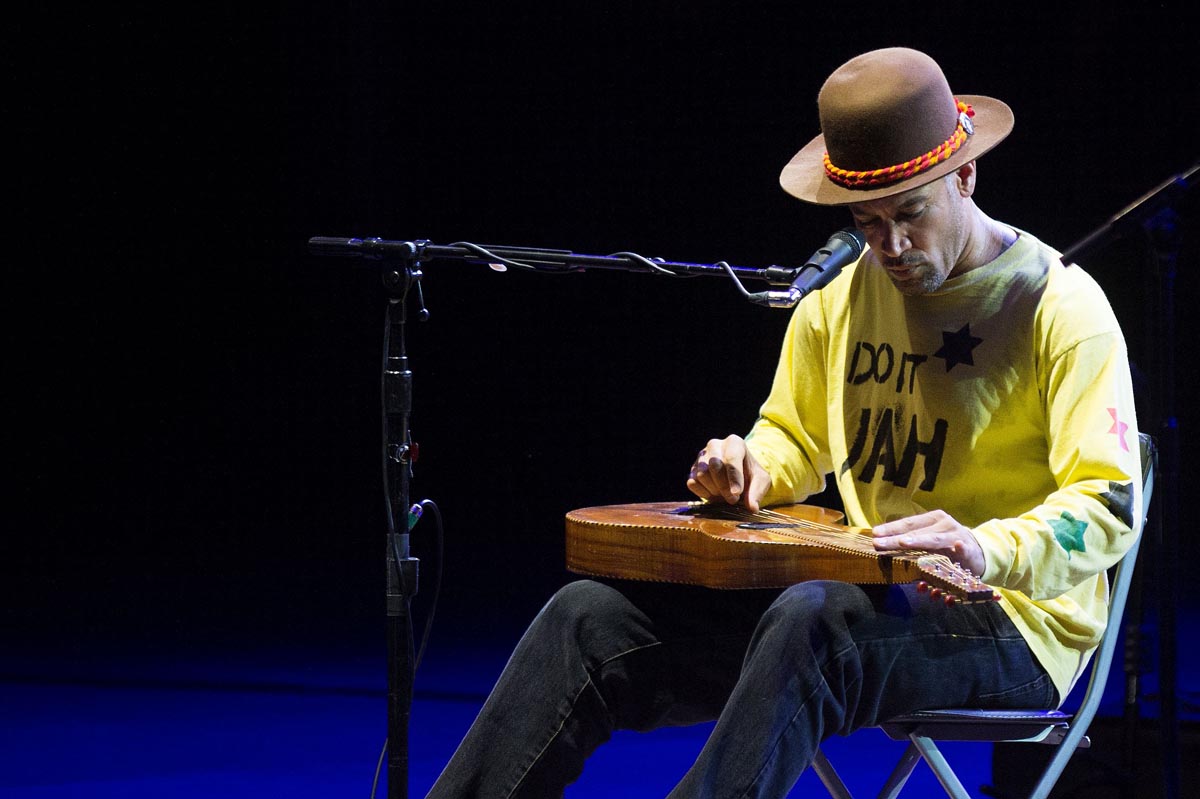

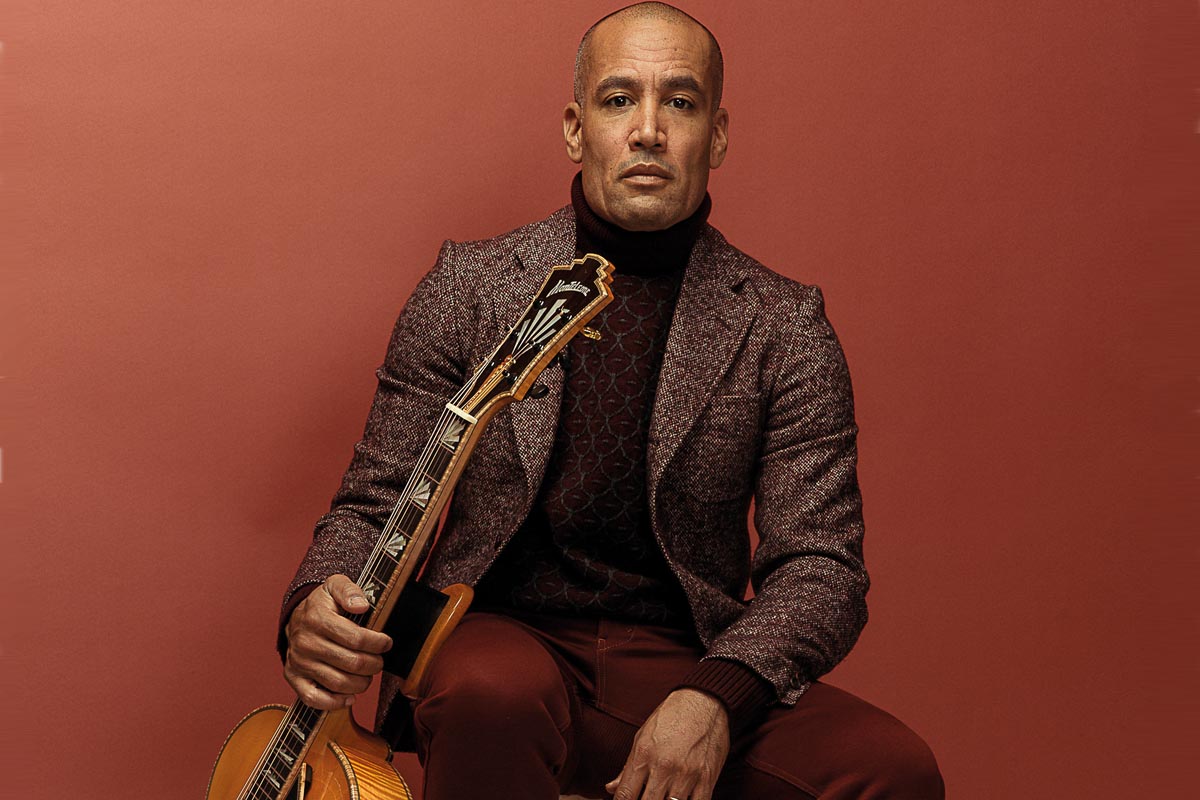

Ben Harper: “There’s a devotion that comes with a lifetime commitment to the instrument, and I hope you can hear that in the melodies”

Harper discusses the inspirations and perspiration that went into his novelistic lap-steel album, Winter Is For Lovers

Ben Harper is constantly looking for inspiration. The singer-songwriter/guitarist keeps an ever-watchful eye on his internal sonic clock for guidance on what direction to go next. That desire to dabble wherever his muse takes him has led to a variety of projects.

He’s doing everything from recording with his longtime backing band, the Innocent Criminals, and teaming up with music greats such as Blind Boys of Alabama, Charlie Musselwhite and Mavis Staples to collaborating with supergroup Fistful of Mercy (also featuring Dhani Harrison and Joseph Arthur) – and his mother, Ellen.

While the three-time Grammy winner has accomplished quite a bit as a performing musician, he remains committed to pushing the musical envelope. Recently, his internal clock told him it was time to record his first instrumental album, the 15-song Winter Is for Lovers, which came out in October.

That’s not to say his prowess on guitar – specifically slide and lap steel – has been lost on fans or himself. Rather, he wanted his guitar to be the focal point this time.

“I’ve been taking aim on this record for a long time,” Harper says. “There’s always a number of directions I can go in, but this one was raising its hand the highest. There was a certain point a year and a half ago where it was the only thing I was working on. And that’s usually a signal that when I end up focusing on a specific sound, it ends up taking over and leading the charge.”

He attributes his specially crafted Monteleone lap steel for providing the impetus for the project. In 2017, John Monteleone gave Harper the guitar, which was dubbed the “Radio City Special Deluxe,” during a visit to his guitar shop. It was the first lap steel model that Monteleone had created.

“The making and construction of that instrument kicked it into high gear, for sure, because [it] was everything I had dreamt, and more,” Harper says.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Fulfilling his vision for the album came with unique challenges, most notably not being able to hide behind his voice. Instead, he had to adjust to the “physics of just being stripped bare, under really fine-quality microphones, without a voice or drum set to hide behind.

“Having that much focus on every single note and overtone, for one song, it’s one thing. For two or three songs, it’s one thing,” he says. “But for an entire album, I had never been down that road.” In addition, he had to be realistic about how the songs would sound, which includes coming to terms with the fact that the sonics might not always be pristine.

“I’m a perfectionist, but I also like to let things be honest and raw. Not that perfection isn’t honest and raw, but you don’t want to sanitize it. So I had to find that balance between keeping it clean but keeping it rough,” Harper says. “Every once in a while, the string finds its way to muting out sooner than you’d want, or a harmonic rings out louder than you had expected in that moment.

I’m a perfectionist, but I also like to let things be honest and raw. Not that perfection isn’t honest and raw, but you don’t want to sanitize it

“And just letting it be a living, breathing sonic organism compared to actually trying to conform it into being a sonic robot was important to me because not everything needed to be quantized and aligned. And there’s no click track. There’s no roadmap. It’s really just me sitting down with my instrument.

“If I had been playing solo guitar for the last 27 years, then this would be something that was routine to me. But while I do solo work in my sets every so often, that’s different than doing it for a lifetime. And there’s a responsibility that comes with being that stripped down. It leaves you with no choice but to be fully exposed.”

Lap Steel Influence

As he focused solely on guitar for Winter Is for Lovers, Harper found freedom to move unopposed between his many influences, showcasing his wealth of musical knowledge. Flamenco, classical, Hawaiian and blues are some of the textures that can be heard on the set, which journeys around the globe with titles such as Joshua Tree and Istanbul.

“I’m hoping that 10 years from now someone will come along and say, ‘Oh, that’s its own style. That’s its own sound.’ It’s influenced by, but it’s none of the above, kind of thing,” he says. “That’s the dream… Hopefully, it’s unconventional enough to define itself, but we’ll see. We’re all just lazy, though, aren’t we? Because we all want to say, ‘Well, it’s connected to this, or connected to that, or connected to the other.’ But none of us are ever brave enough to say, ‘Hey, this is its own voice.’

There’s a certain amount of devotion that comes with a lifetime commitment to the instrument, and I hope you can hear that in the melodies

“But I’ve just loved the journey. My guitar is my horn. My guitar, that’s my axe, and there’s a certain amount of devotion that comes with a lifetime commitment to the instrument, and I hope you can hear that in the melodies in a way that isn’t connected to anyone but me.”

Since he was a kid in the 909 “Inland Empire” area code of southern California, Harper has written music with that unrelenting curiosity. In addition to his mother’s diverse record collection, he found inspiration anytime he’d step foot in the Claremont Folk Music Center, which his family owns.

In 1958, Harper’s grandparents, Charles and Dorothy Chase, opened the instrument shop and expanded it over the years to foster music education in the community. His mother Ellen later took over as manager of the store and, recently, Harper bought the store to ensure it stayed in the family.

For many years, Harper’s grandmother – who he calls the “musical matriarch” of the family – helped dictate the daily soundtrack heard in the store.

“There’d be debates between the employees, which were all family, and my mom, and myself as a youth, and my grandfather,” Harper says. “We’d all challenge, we tried to get my grandmother to play different music, and she would, but she truly ruled over the record player in that music store. And it was our good fortune, my mom’s and mine, that she had impeccable taste.”

My grandmother was committed to American music before it had an A on the end. Before blues, folk, roots and outlaw country was Americana, it was just American roots music

That repertoire included blues, folk, Hawaiian-based music and other forms of roots music. Harper recalls hearing Reverend Gary Davis, Mississippi John Hurt, Blind Willie Johnson and Robert Johnson for the first time in the store.

“My grandmother was committed to American music before it had an A on the end,” Harper says. “Before blues, folk, roots and outlaw country was Americana, it was just American roots music. And my grandmother was committed to it. She was committed to playing it and she was committed to being a fan of it. So, Grandma Dot, Dorothy Chase, would play it.”

The store also hosted a diverse selection of traveling musicians, which gave Harper a chance to examine their playing from only feet away and – in some cases – meet the artists and help string their guitars.

Doc Watson, John Fahey, Ry Cooder, Leonard Cohen, Taj Mahal, David Lindley and Jackson Browne are just some of the names that set foot in the shops. Pedal steel players, such as the late Chris Darrow of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, especially piqued young Ben’s interest.

“Pedal steel players, in the middle of their route, when they’re headed out Route 66 from LA to Chicago, would stop in my family’s music store, pull their semis as close as they could get and walk the rest of the way, come in and play a pedal steel,” he says. “[I thought,] ‘Wow, that’s special. And I don’t even play pedal steel.’ It’s the sound, the textures, that hit me early.” So much so that he eventually decided to get his own – sort of.

His grandfather offered his Weissenborn lap steel, but with a catch – he had to buy it or work it off. His family couldn’t afford to just give away instruments. So, back in the late Eighties, the teenaged Harper slowly worked off the $500 needed to obtain the guitar.

“If you wanted an instrument from the family, you had to either buy it or work it off,” Harper says. “I remember working it off in my family’s music store for my first Weissenborn, which I still have.”

Harper has since obtained other guitar brands, including a signature lap steel made by Billy Asher, an aluminum lap steel by an Italian company called Noah – and his Monteleone. He’s found each guitar has its own personality and a “subtlety of tone.” Some have subtle differences on the top end and low end. Certain songs require a specific lap steel.

It’s fascinating what the different tone bars will give you – the different radius on the different tone bars

“It’s fascinating what the different tone bars will give you – the different radius on the different tone bars,” he says. “At a certain point, the subtle differences are glaring. And that was one thing about this record – the subtle shifts.

“If I didn’t come back and sit in the same chair position with my instrument the next time I played, it would sound different. So there was an exactness and precision that went into just the sonics, never mind the playing, but the sonics as well as the playing. So that was a trip, just having to really focus.

“And then the different steel. I’ve got lap steel bars that are made of glass, I’ve got them made of ceramic, I’ve got them made of steel-coated brass. And the different brass are different in density because they have a different zinc content. So the different weights of the bars played a role in the tone and texture. Finding all of that, finding the final absolute sound we wanted to set sail with. There was a lot that went into it.”

He attributes Taj Mahal and Darrow for helping with this learning curve. He fondly recalls Darrow teaching him how to play his song Whipping Boy on lap steel. Harper eventually covered the song for his debut album, 1994’s Welcome to the Cruel World.

“Getting to sit down with Chris Darrow and have him teach me note for note, that has played a bigger role in where I am today than anything,” Harper says. “Having him teach you one of his songs, that’s pretty much as good as it gets. From the perspective of someone who is learning, and up and coming, and trying to commit themselves to an instrument, the fact that he heard something in me that deemed worthy to teach me that song was a special moment.”

Learning to play lap steel is an ongoing life venture, he says. “I admit it, because it still informs me in such different ways,” he says. “I want to go to one of those steel guitar summits. I want to go sit and watch some unorthodox steel guitar music. There’s a summit in North Carolina with all steel guitar the entire weekend.

“I got advice early on from John Lee Hooker,” he continues. “John Lee Hooker had a connection with my guitar playing and said, ‘Do more of that. Just focus on your guitar – and your guitar playing.’ He was an early supporter of my guitar playing and said, ‘Make sure you keep doing that, because that’s something different.’ I was like, ‘Okay, right on, Mr. Hooker.’”

Life’s Journey

After reading David Foster Wallace’s 1996 novel, Infinite Jest, which combined a series of short stories to create a bigger narrative, Harper realized he could have a similar narrative structure with the ideas he was coming up with.

“Infinite Jest, as far as structure, played a major role in how I ended up being able to weave and tie this record together and transform it into one single piece of music, the way David Foster Wallace did,” Harper says. “The fact that I was working on that record at the same time as I was reading that book made it clear that it was time to take a more brave outlook at how I was bringing this record to life. Had I not been reading the book, I think it would’ve been a different record.”

Harper decided to name the songs on the album after geographic locations because “most of them were written on the road.”

For example, London was influenced by British guitar players, such as Richard Thompson, Nick Drake, John Martyn and Jimmy Page. Meanwhile, Paris was inspired by the blissful feeling of a walk in a park in the French city, buoyed by Harper’s meditative slide guitar.

“Being a traveling musician around the world you’ve got to pick up on the resonance and the frequencies of the places you go,” Harper says. “I just love the fact that it’s come to pass as I was able to live it and explore and [use my] experience in making a record like this.”

One reason the album works, Harper says, is his recording engineer Sheldon Gomberg. While it might have been tempting to simply hit record, Gomberg kept him focused.

“I needed Sheldon because I was just doing numerous takes, and we were really fishing for the magic take,” he says. “And Sheldon would keep me, and prevent me, from getting in my own way in that department so that I didn’t go overboard in making it too clean. He provided me a platform in which to keep it raw.

I’m curious where I go from here as far as instrumental recordings. I love doing it, and it’s been a growing and learning experience for me

“He kept reminding me, ‘It’s okay. It’s okay that it has the immediacy of it being raw and in someone’s living room.’… I was glad that I was able to leave that to Sheldon. I was just able to focus on playing and enjoy. I had a lot of joy in this record. Every moment of recording this record felt great.”

Harper doesn’t know yet where he’ll go with his next album but wouldn’t be surprised if he made another instrumental album at some point.

“I’m curious where I go from here as far as instrumental recordings. I love doing it, and it’s been a growing and learning experience for me,” he says. “So, it could be just the embarkment point, or this record could be that journey and I move away from it. But I’m going to be curious to see what calls out creatively in the future for instrumental records and recording with just the guitar. I hope it’s the beginning of something.”

- Ben Harper's new album, Winter Is for Lovers, is out now via Anti.

Josh is a freelance journalist who has spent the past dozen or so years interviewing musicians for a variety of publications, including Guitar World, GRAMMY.com, SPIN, Chicago Sun-Times, MTV News, Rolling Stone and American Songwriter. He credits his father for getting him into music. He's been interested in discovering new bands ever since his father gave him a list of artists to look into. A favorite story his father told him is when he skipped a high school track meet to see Jimi Hendrix in concert. For his part, seeing one of his favorite guitarists – Mike Campbell – feet away from him during a Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers concert is a special moment he’ll always cherish.