Billy Bragg: “Most of my chord shapes are fists. It’s just the way I play – I’m hanging on for dear life”

Billy Bragg is a punk-powered agitator turned historian of early rock ’n’ roll. We joined him to talk about his new album and discuss why Lonnie Donegan ain’t no joke…

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

While some artists found it difficult to pick up a guitar during the national lockdowns of 2020, Billy Bragg was making his first album in eight years, entitled The Million Things That Never Happened. He’s always been one of the most distinctive, unflinching yet compassionate voices in rock.

Emerging from the busking scene, songs like A New England from his 1983 debut album, Life’s Riot With Spy Vs Spy, confirmed him as a laureate of the London streets with an unvarnished ‘chop and clang’ style on guitar that matched the energy and honesty of his lyrics.

His main squeeze back then was a rare Burns Steer semi-acoustic that’s still by his side today – along with a cherished collection of National Resonators and Gibson flat-tops that partly reflects Billy’s interest in old-school country music and Americana, an influence that has grown like a wildwood flower in his music since the 1998 album with Wilco, Mermaid Avenue, which saw Bragg set previously unpublished Woody Guthrie lyrics to music for the first time.

In fact, charting the connections between Americana, youth politics and the nascent British rock ’n’ roll scene of the 50s became a bit of a mission for Billy, inspiring him to write the book Roots, Radicals And Rockers: How Skiffle Changed The World, published in 2017.

We joined Billy among his books and guitars to talk about his new album, go-to instruments and learn why, without Lonnie Donegan, there would have been no British Invasion of the 60s.

What spurred you to make The Million Things That Never Happened?

“Well, I got round to thinking about making an album. And after the second lockdown, I thought, ‘Wow, this could just go on and on and on… I really need something to focus on here.’ We’d been talking about making an album anyway, but I imagined I would spend a year on the road, trying out songs in soundchecks, which is my usual MO – but, of course, that didn’t happen.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“So I got in touch with Romeo Stodart, and Dave Izumi who owns a studio down in Eastbourne [Echo Zoom Studios]. And in between the lockdowns I went to see them, and we sussed it out and it all looked great and everything. We booked some time in December – and, of course, that wasn’t possible, either, but Dave and Romeo are in a bubble so they could work in the studio.

“So they said, ‘Well, just send us some demos.’ It’s not a way I’ve ever worked before, but it was really interesting because I had wanted to work with them, because I really like how they arrange songs. I think after making records as long as I have, always in the back of your mind is a sort of dread about unconsciously repeating yourself.

“So I thought if I worked with them, then they could take my ideas and run with them. They would have done that anyway, but [ordinarily] I would have been sitting behind them in the control room raising an arched eyebrow when they put the third Mellotron on. Whereas, with my not being there, they just did it and sent it to me and I was like, ‘Wow, that’s amazing. I really like that, let’s keep on going in that way,’ and so it worked out from there.

“I finally did get to go to the studio in April, by which time I had written some more songs, so we did do some live songs. But, basically, it was me sending them very basic guitar vocal demos, literally played through this microphone [that I’m speaking on], on to this computer and they would send me back the finished track. I thought it was a really good way to work.”

You mentioned that being on the road was previously a reliable way to develop new material…

“Yeah, I had a song once that I was writing on the way to a gig in Brighton. This was in the old days when I didn’t have a phone to sing into – and I had to stop at two petrol stations to write down the lyrics. And when I got to the gig, I really needed a kip before the soundcheck. So I had a kip, but this song kept waking me up with more lyrics.

“I eventually got the song and I played it that night, but when I got back from the gig I went to bed, put my head on the pillow and it woke me up again with more lyrics – so I had to get out of bed and write it down. The song didn’t let me go until it had said its last bit.

Where does that come from? I have no idea how to evoke that or where that comes from, but when it happens, it’s both brilliant and annoying at the same time. It’s, like, ‘Okay, I’ve got it, leave me alone…’ But, you know, there is no one way to write a song – any way that gets the song written is a good way to write a song.”

There’s a lovely strand of country music and American folk to your sound on the new album. Where did that come from?

“It’s a very interesting one. I think it’s where the craft of songwriting is still appreciated, so that’s a good place for me to be. Obviously, my connection with Joe Henry brings me into that arena, but mostly I think it was Mermaid Avenue that pitched me out of what I was before and into what I have become since.

“At the time, that was more usually defined as ‘old country’, but now it’s become Americana and that’s great. The Americana Music Association has actually invited me to their awards a couple of times now.

“The first time I went, I was giving an award and the second time I went I was getting an award. But the first time, I said, ‘Just so I know what we’re talking about, what exactly is Americana?’ And they explained it to me as being any music that’s inspired or based on the roots music of America. And I was like, ‘What, you mean like skiffle?’ And they were all like, ‘What’s skiffle?’

“It was over dinner and we had this long conversation, and that’s how I ended up writing a book about skiffle. I realised that there was a huge gap in knowledge about it – particularly for the Americans who loved The Beatles and all that. If they don’t know about skiffle, they’ve kind of missed the [most important influence].

Skiffle is absolutely crucial because it’s the thing that introduced the guitar into British pop music

“And skiffle is absolutely crucial because it’s the thing that introduced the guitar into British pop music. Beforehand, no British singers played a guitar. But after that, the guitar became the symbol of why they were different from their parent’s generation.

“It’s a revolutionary culture, skiffle, because it took the means of production away from the big songwriting conglomerates, the Tin Pan Alley guys, and gave it to kids in the street who could then connect with someone like Lead Belly or Woody Guthrie and, from that, make their own music. It’s a really, really crucial period and the guitar is absolutely dead centre in it.”

So many iconic guitarists idolised Lonnie Donegan when they were growing up…

“Yes. Well, when I was interviewing people for the book, Van Morrison said to me, ‘The thing was all those guys who wanted to be Elvis, but you can’t be Elvis if you’re from Britain.’ Another thing that inspired me to write the book was when we played Glastonbury with The Blokes. The Stones were on later, so we rehearsed Dead Flowers.

“We really enjoyed doing it so we kept it in the set – our festival set, anyway – and I would introduce it by talking about how the Brits invented Americana, talking about Donegan, you know.

“When I said his name, every time I said it, wherever I was in the UK, there were audible sniggers from the audience and it really annoyed me. It really annoyed me. I thought, ‘This is wrong because when you talk to someone like John Peel or Van Morrison, they’d tell you that something incredible happened to them when they heard Rock Island Line… So that’s how I ended up banging out the book.”

There was a kind of a feedback loop, wasn’t there, between British teenagers listening to American blues records in the late 50s and early 60s, assimilating that sound into skiffle, before going on to make it big in the States themselves during the British Invasion…

“Exactly, it happened in a really weird way… One old guy who had been a skiffler said to me that the average skiffle kid [in 1950s Britain] felt they had more in common with African-American musicians than they did with their own dads. Which is amazing when you think about it, isn’t it?

“Then when the BBC wouldn’t play Rock Around The Clock the skifflers were like, ‘You know, you’ve rationed everything. You’ve rationed food. You’ve rationed clothes. You’ve rationed sweets. You’re not going to ration rock ’n’ roll. If you won’t play Rock Around The Clock, if you won’t play this new music, we’re going to play it ourselves.’

We still live in the world that they created in the 60s, don’t we, really?

“So the numbers of shitty Czechoslovakian guitars that they sold in 1957 [as skiffle took off] went from 5,000 a year to 250,000 a year. Divide that by five and that’s how many bands there were: 50,000 bands and nowhere to play because there were no clubs – so they were in school halls, they were in scout huts… but they were everywhere.

“It was a playground craze, you know? That invention of the teenager in the UK didn’t come over [to Britain from somewhere else] – that was a watershed. That generation was a watershed generation. And we still live in their world, you know. We still live in the world that they created in the 60s, don’t we, really?”

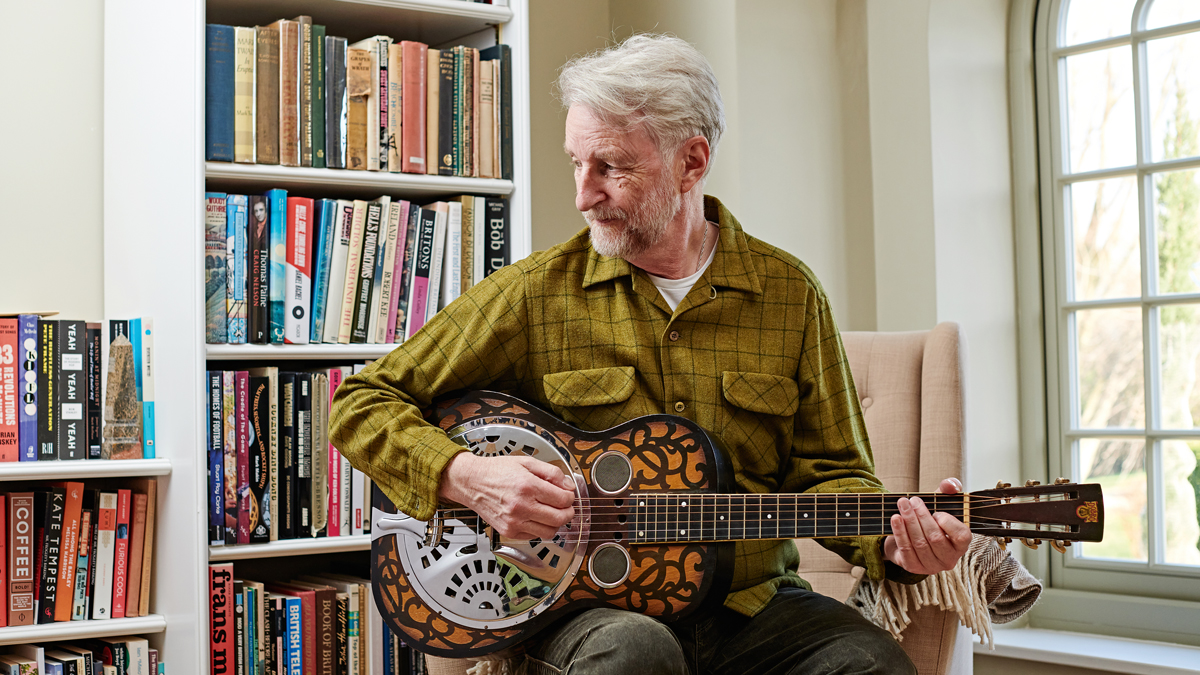

What are your go-to guitars at the moment?

“I have a Gibson LG-1 that I’ve had sitting in my office for a long time. I mean, that’s been around for ages. I took it to the Mermaid Avenue sessions, actually, so that’s what I’m playing on Mermaid Avenue. My son borrows that now – it kind of disappears off, so I’ve got a Gibson J-45 acoustic propped up against the chair over there.

“My partner bought me this stool with a little cutout in it, so it can actually function as a guitar stand as well. You can sit on it, play the gig and then put the guitar up against it. And she inscribed one of my lyrics around the top of it, which is even lovelier. So I have that over there in the corner at the moment with the Gibson.”

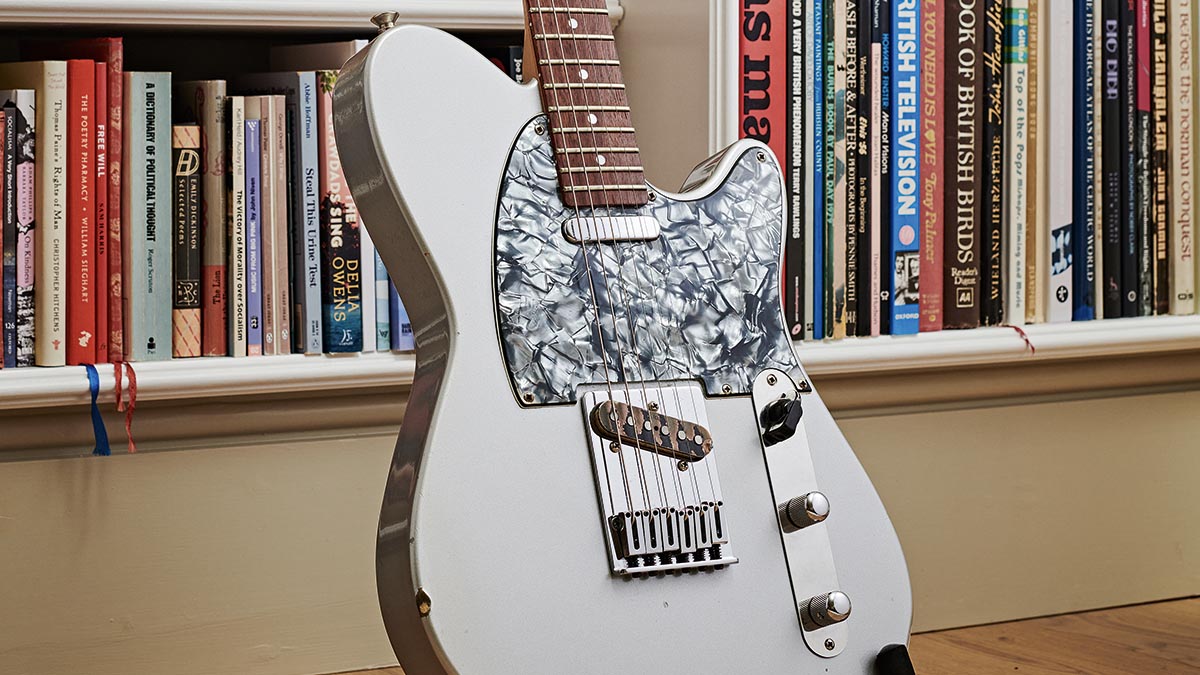

Billy’s rare Burns Steer from the early 80s, which is effectively a prototype that got sold into the trade by Jim Burns.

The steel plate on the guitar’s top is an integral part of its sound, Billy says. Later Burns London reissues featured a lighter plastic plate instead.

The logos of rare, original Steers say only ‘Burns’, rather than ‘Burns London’.

You used to play a green Burns Steer a lot early in your career – do you still use that?

“Yes, I do. I take it out on the road with me sometimes. Before the lockdown, I was doing these three-night stands where I was playing songs from my first three albums… The Burns Steer really came into its own on that.

“I wasn’t using it so much by the time of the second three albums – with Workers Playtime [1988], I was thinking more like I was a soul singer then, so I was using a really nice 1965 black Telecaster, which I’ve still got, but I don’t really play any more – it needs setting up. But I still get the Burns out and it still takes everyone’s head off when I do that!

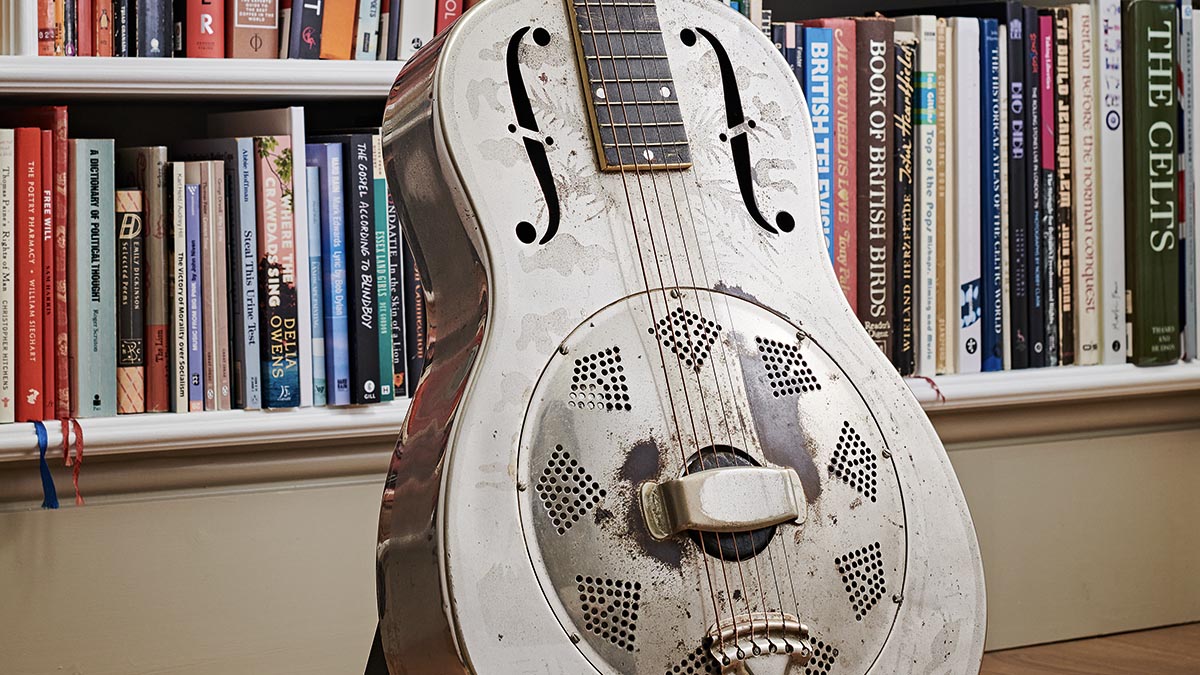

Billy’s National Style ‘O’ resonator, in Variation 2 spec, serial no S788, which dates from 1930.

What appear to be clouds and palm fronds are still visible around the f-holes. Such designs varied tremendously in Nationals of the era, but the differences have been documented by historians and serve to pin down their exact age and type.

Patina and playwear on the vintage National, which has loads of character.

“I was very lucky to get that guitar because I don’t think they ever went into [mainstream] production. All the ones I’ve seen – and I’ve seen pictures of about eight or nine of them – are all different. A guy who used to work at Burns got in touch with me and told me he had made my guitar.

“He had sent it up to London with Jim Burns, to a [trade] fair, and thought he was going to get it back because he made it for himself, really – but it didn’t come back. We worked out the timing of that and it was about a week before I saw it in a guitar shop in Hammersmith and bought it. It’s definitely that one because it has the same serial number. So there aren’t loads of them out there if I lose this one.”

The Steer looks part-electric, part-acoustic in design. Is it chambered?

“It is chambered, yes – the soundhole has bits going off from it. It’s not hollow-bodied, though, it’s quite heavy, and I think a lot of it is to do with the metal plate across the front. That’s a stainless-steel plate.

“When they did the reissue they put a plastic plate on there instead and I’m not sure it was the same [sonically]. Burns London very kindly gave me one and I got a plate made up and put it on there just to give it that little bit more. Because there is something about the Burns originals that have that [steel plate] on the top there – it’s not quite what they used to call ‘Wild Dog’, but it’s a sound all of its own, you know?

“That’s important because I don’t use any pedals. All I have is an inline tuner. I’m a philistine in that sense, in that I believe it’s all here [in the hands and guitar] rather than all down there… I understand why people use pedals and they amaze me, but when I come out at festivals and I’ve just got a tuner, roadies look at me like, ‘Are you taking the piss?’”

So no effects – but do you use a lot of guitars on stage?

“I’m really basic when I go out on tour. I’m basically using two guitars in between an electric and an acoustic. My go-to acoustic is a Montana J-45 [Standard]. I’m not hugely precious about guitars on the road, though. I’ve got some lovely old 1930s Nationals – that’s my fetish, I suppose you could say. I took one of them to the Mermaid Avenue sessions, but I don’t take them out on the road.

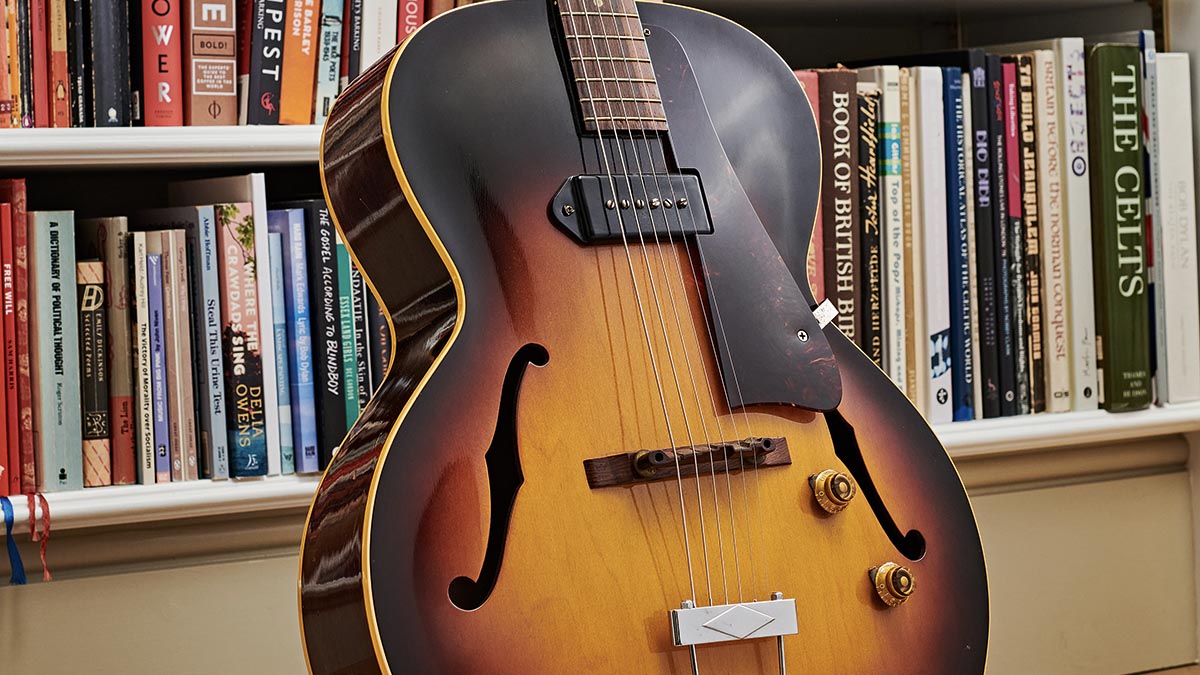

“I’ve also got a really nice electric guitar made by a guy named Jim Dyson. He’s an Australian guitar maker. He doesn’t make guitars any more, but he made really, really great pickups.

“When I was touring with Billy Bragg & The Blokes, I had Lu Edmonds and Ben Mandelson with me who used to play in 3 Mustaphas 3. They played kind of world music instruments and they really liked Jim’s pickups. So he came to a show in Melbourne with a load of pickups, but also he brought this guitar that he calls a Tone Deluxe TV.

“I’m not sure he made many of these, either, but it’s quite light. It’s like a Telecaster but with an extra click on it, an extra [pickup selector] position on it. But most importantly – and this is absolutely crucial for me – it stays in tune no matter what you do to it.

“My style has been referred to as ‘chop and clang’ and I quite like that. It comes from thinking of the guitar as a percussion instrument rather than as a purely melodic instrument… it’s about punctuation, almost. The rhythm is going in my head and I’m trying to click it in there to fit around the words I’m singing at the same time.

“As a result of that I’m giving the guitar a lot of stick. Most of my chord shapes are fists. If you give me a lightly strung guitar I’m going to pull it out of tune all the time. It’s just the way I play; I’m hanging on for dear life as we’re going through the song. So I need something that’s going to stay in tune – and the Dyson you can put it in a 747 back from Australia and it won’t go out of tune in the hold, you know? That’s the ideal Billy Bragg guitar.”

- The Million Things That Never Happened by Billy Bragg is out now on Cooking Vinyl.

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.