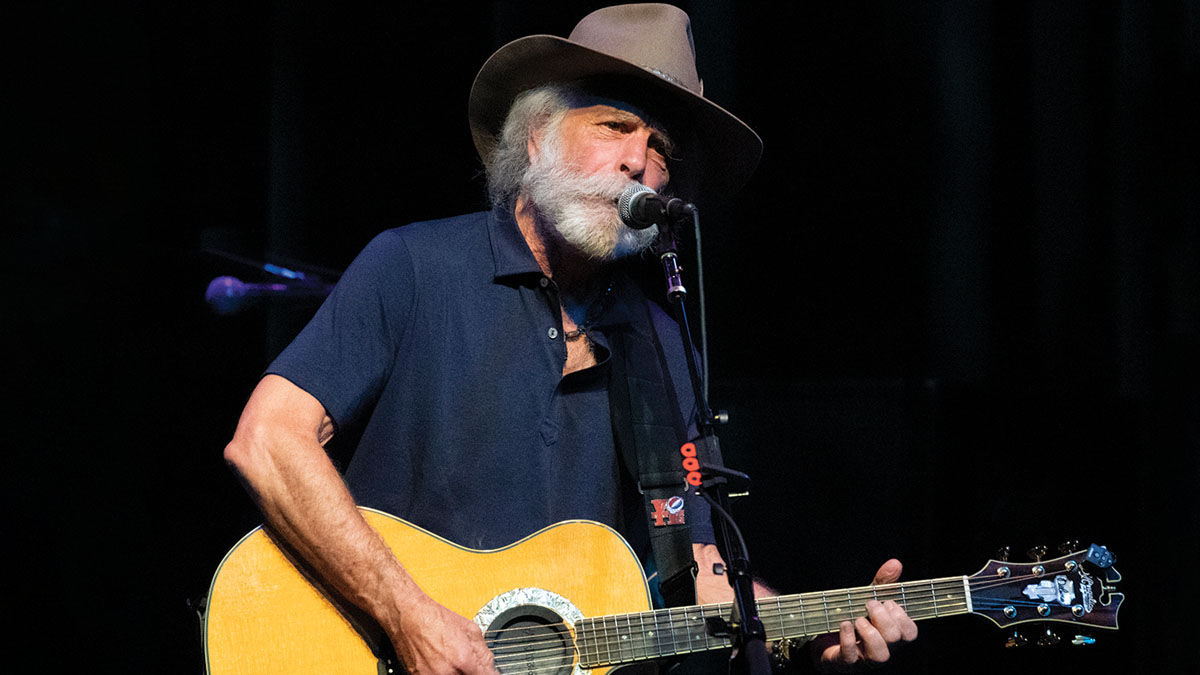

Bob Weir: “I’ve pretty much abandoned signal processing. The guitar itself has such variety to offer and it’s so much more elemental”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

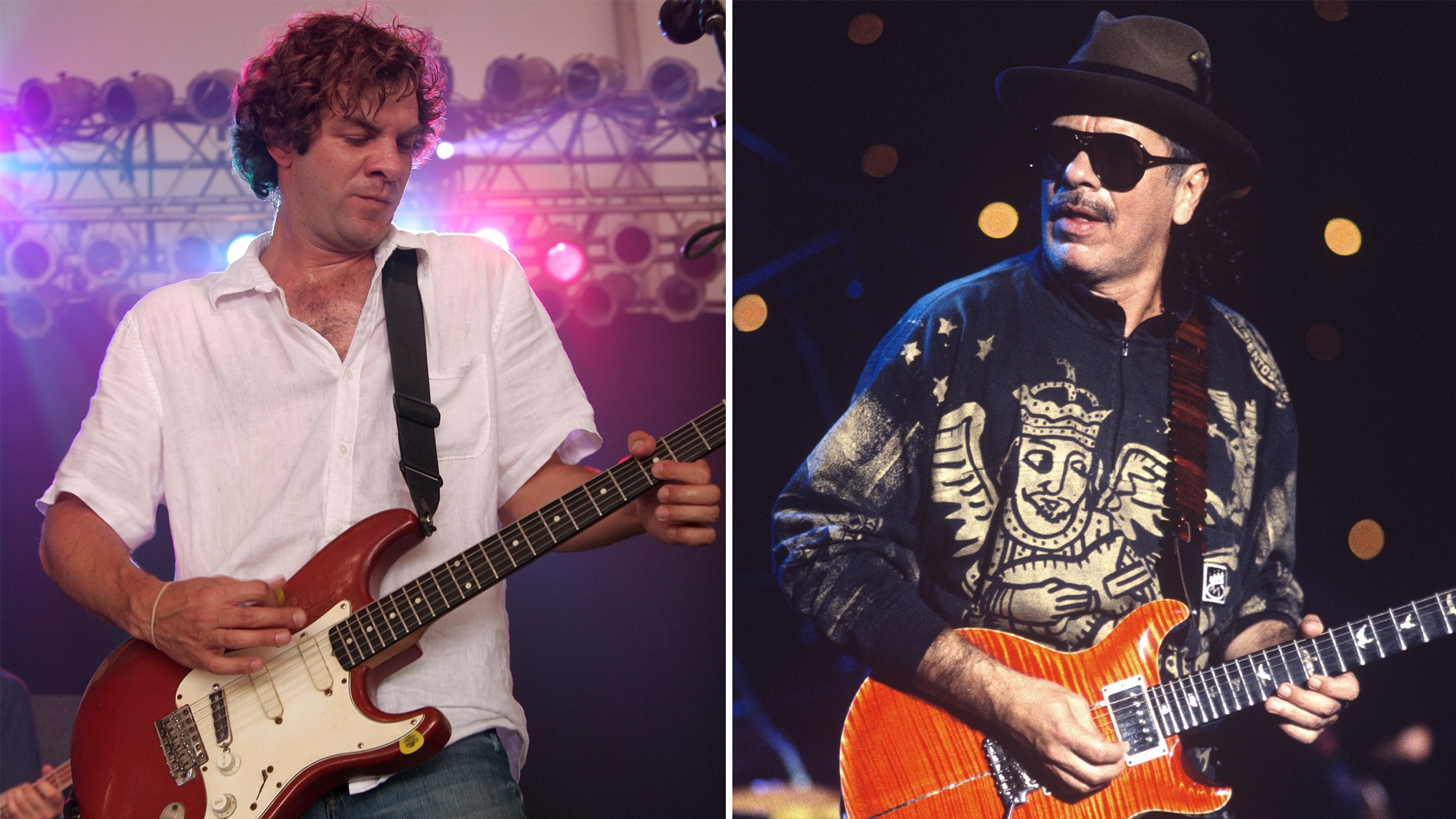

Bob Weir is ridiculously busy at age 74. The founding member and rhythm guitarist of the Grateful Dead now spends his summers touring stadiums with Dead & Company, the group that also features Dead drummers Bill Kreutzmann and Mickey Hart, guitarist John Mayer, bassist Oteil Burbridge and pianist Jeff Chimenti.

Since 2018, he’s also toured with Bobby Weir and Wolf Bros, a group that began as a trio with bassist Don Was – best known as a producer of the Rolling Stones, Bonnie Raitt, Bob Dylan and many others – and Primus drummer Jay Lane, a longtime Weir collaborator. The band has slowly expanded into a 10-piece juggernaut.

They are captured on their first album, Live in Colorado, which features highlights from a 2021 tour of the Centennial State, which represented their first live performances in front of an audience in almost a year, due to the pandemic.

It’s a very strong collection of Dead and Weir tunes, all of which take on a different form in the group, with his distinctive rhythm playing and vocals center stage atop slinky, swirling textures. In October, the group will play four shows with the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington, D.C., performing a concerto of mostly Grateful Dead music, something they’re still hammering out onstage and off.

Weir also has been working with Taj Mahal on a stage musical about Negro League baseball icon Satchel Paige, as well as an opera and a memoir. He’s also become an unlikely workout icon, posting his daily exercise routines on social media to the delight of fans. We caught up with him on the phone as he was preparing for Wolf Bros’ spring tour.

Your endless activity is inspiring, and the familiar songs on the new live album sound totally renewed. How did Bobby Weir and Wolf Bros come about?

“I started a little trio, the Wolf Bros, and it’s become a… I guess the word is dectet. There’s 10 of us! It can operate in various configurations from three to 10. And now I’m working with a symphony orchestra, which God knows is fairly rewarding. It took a lifetime to crowbar the door open to do all this stuff, and here it is – all the stuff that makes life worth living.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I woke up one morning with this dream in my head; I was playing in a trio with Don and Jay. I just rolled over, picked up the phone and called Don and asked him if he wanted to do this and he said sure. As the band has grown, parts of our show still focus on the trio because we really can do something.”

It took a lifetime to crowbar the door open to do all this stuff, and here it is – all the stuff that makes life worth living

Then you added pianist Jeff Chimenti, who you’ve played with for years, and pedal steel player Greg Leisz, an absolute master as a soloist and at chordal coloring. How did he come into your orbit?

“Don suggested we give him a try. I halfway grew up on country music, so I’ve always had a soft spot in my heart for pedal steel. The instrument is pretty much relegated to country music, but it’s capable of so much more than that. I think you should find it everywhere, but it’s so complicated and there are so few pedal steel players. We don’t have Greg all the time. Sometimes we use Barry Sless, who’s also great.”

Then you added the horn section and some strings. Is this all in preparation for playing with the orchestra?

“Sort of. We still gotta workshop this, but we selected the guys to tour with us with the idea that they’d develop a library of riffs they would then use to lead their instrumental groupings; the violinist would lead the violins and feed them a line, for instance.

“We have about six months to figure out exactly how we’re going to do this. They’ll be reading, but the section leader will be improvising; we’ll be feeding them lines to play and they’ll never be interpreted the same.”

Is this an effort to merge the symphonic tradition with your love of improvisation?

“Yeah, that’s what we’re up to. The rehearsals we’ve had with the Marin and Stanford Symphony orchestras have been pretty amazing. It works. Bach was famous for making enormous classical pieces out of folk tunes, which is more or less what we’re up to here with Grateful Dead songs. We’re taking music that’s drawn from the folk traditions and bringing them to full classical orchestration.”

20 years ago, when I was interviewing you for Guitar World, you said, “I never had too much of an idea of what I’m doing.” Do you still feel that way about your playing?

“I think that through dogged persistence, I’ve found ways to pull an awful lot of variety out of the sounds an electric guitar can produce. I feel like I’m starting to get a handle on how to bring it all together and make music.

“I’ve discovered that certain configurations of instrument design and pickup design will give me a broader spectrum to work with, so I’ve pretty much abandoned signal processing. The guitar itself has such variety to offer and it’s so much more elemental. I don’t use delays or envelope filters much anymore because the guitar itself tells me all I want to hear.”

You’ve talked before about how much your style developed by playing with Jerry Garcia and Phil Lesh, who had such distinct approaches to their instruments. [Dead & Company bassist] Oteil [Burbridge] and John [Mayer] are very different players. Do you continue to evolve playing with different people, or do they have to fit in with you at this point?

“No, no. We fit in together as best we can, which is essential to our kind of music. We just find the center and go for that. The adaptation has gone both ways. When Oteil is at his best for our music is when he’s framing the songs with a bass line that some of them really have never had, because Phil was playing lead bass – a different deal. Some of those songs never really had a traditional bass line. Oteil is able to find that, and I think the songs are thankful and have grown from that.”

People think we can’t wait to get on stage. I want to play, yes, but those last few steps on stage are like walking into a torture chamber every time

Live in Colorado is a great example of how you can play the same catalog differently in different settings. One great example is your riff that kicks off Big River, which is quite different from the type of thing you usually play.

“Yeah. It’s more of a traditional lead guitar riff that I found, but it’s actually something I got from what Jerry used to play on the song, and then it sat with me for a couple of decades after he checked out. It’s my interpretation of that. All this comes from our mutual understanding of what Johnny Cash really wanted with that song.”

Are there other songs where Jerry’s stuff seeped into you and came out without you really consciously doing it?

“That was actually happening even when Jerry was still alive. Like the riff that I do in Wharf Rat, which I think I pulled out of Jerry’s psyche one day when we were rehearsing. When I got that right, I could click with it and he started answering and started framing that, so I stuck with it, and it’s stayed with the song for five decades now.”

You’ve said you still have stage fright, which seems amazing. You’ve probably performed in front of as many people as anyone ever has. Can you describe that?

“It’s the anticipation, the time before walking out. There is a moment onstage when I think, ‘Thank God, I’m out of here.’ I can forget myself, leave the building and let the characters in the songs have my body, my spirit and everything else. I can take a breather and not have to worry about it. As far as the size of the crowd, a living room is the toughest for me. Oftentimes the larger the crowd, the way easier it is for me.”

It’s less personal. I’ve heard Jerry had stage fright, too.

“Oh yeah. And you could make the case that that’s what killed him, because he used those drugs to dull the stage fright, to dull the pain of it, because it physically hurt. We talked about it a fair bit. We compared notes on how we dealt with stage fright. It wasn’t an ongoing conversation, because there wasn’t much new to add to it after the first six months that I’d known him.

“After we realized we were in the same boat, there wasn’t much more to say about it, but we would sometimes give each other looks that said, ‘It’s okay, I got past it. How are you doing?’”

Gregg Allman also had stage fright, and to look from the outside it’s impossible to imagine that could be possible for the three of you.

“People think we can’t wait to get on stage. I want to play, yes, but those last few steps on stage are like walking into a torture chamber every time. It’s not easy.”

- Live in Colorado is out now via Third Man.

Alan Paul is the author of four books, including Brothers and Sisters: The Allman Brothers Band and the Inside Story of the Album That Defined '70s as well as Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan and One Way Out: The Inside Story of the Allman Brothers Band – both of which were both New York Times bestsellers – and Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, a memoir about raising a family in Beijing and forming a Chinese blues band that toured the nation. He’s been associated with Guitar World for 30 years, serving as managing editor from 1991 to 1996. He plays in two bands: Big in China and Friends of the Brothers (with Guitar World’s Andy Aledort).