Brandon Kinney Talks Songwriting and Getting His Start in Nashville

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When Brandon Kinney arrived in Nashville 20 years ago, he knew he wanted to work in the music industry. What he didn’t know was that he would find his niche crafting songs for other artists, and he certainly didn’t expect to become one of Music Row’s most in-demand songwriters.

It was a long, slow road from student at Belmont University to publishing deals with Sony ATV, Love Monkey Music and Tom-Leis Music.

Along the way, Kinney worked day jobs, made inroads via colleagues who were already signed and even signed a recording contract as a solo artist. In 2005, Lonestar gave him his first hit when they recorded “You’re Like Coming Home.” His phone started ringing, and in 2009, “Boots On,” a co-write with Randy Houser, became BMI’s second-most-performed song of the year.

Since then, Kinney has been on a winning streak, landing cuts and writing hits for numerous country artists — Randy Travis, Willie Nelson, Jake Owen and Luke Bryan are a few of the names who have recorded his songs. In 2012, “Outta My Head” became a hit for Craig Campbell and was the second-longest-charting song in Billboard history, holding steady for 54 weeks.

Kinney was at the Sony offices for a writing appointment when he took some time to discuss songwriting, Nashville then and now, and what he has learned since signing his first deal.

GUITAR WORLD: What attracted you to the guitar, and when did you begin writing songs?

My dad bought me an electric guitar, but we traded it in for an acoustic pretty quick because, starting out, I wasn’t as much into playing licks or lead parts, and I thought that’s all the electric guitar was for. I said, “I’m going to get an acoustic so I can actually play a song.” I didn’t know anything about playing guitar.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

My interest in music was probably infused in me from birth, because my parents used to turn the radio to a country station and put it in my room by the crib, so that when they had friends over I wouldn’t wake up because I could deal with the noise. They said I was dancing all the time when the radio came on. I just loved music. My mom played piano in church and she would get me up to sing at evening services.

I was playing football, loving football, and I was also into bicycles. I got a head injury from a bicycle accident and it put me out of football completely at the start of my eighth-grade year. My dad played guitar a little bit when he was a kid, and he showed me how to play “Wipeout.” I was bummed out because I couldn’t play football anymore, so he said, “Why don’t we get you a guitar?” We got a guitar and I stayed in my room for hours every day.

That’s all I wanted to do. That probably went on for a month and a half before I started getting interested in writing. I looked at the credits on Paul Overstreet’s record and noticed that there were other writers on there with him. One night, around 1:30, I couldn’t sleep, and this lyric and melody popped into my head. I got up and wrote it in about 30 minutes. I didn’t have a recorder because I wasn’t planning on writing anything. I was not prepared. I was afraid I might forget it, so I played it about a thousand times. I stayed up until probably 3 or 4 in the morning trying to remember it. The next morning I played it again and I played it for both of my parents. They loved it. And I got a recorder.

Were you attracted more to lyrics or melodies, or was there a difference?

I’ve never separated the two. I loved song lyrics, but I looked at it as a whole thing. I wasn’t focused on just writing a good lyric. I wrote what came from the heart the first time, and I thought, That rhymes and that’s cool. But there was no focus primarily on one or the other. To me, it was one vehicle.

When did it become obvious that it was time to move to Nashville?

My dad always encouraged me to be an artist. He thought I needed to be up there like George Strait! I didn’t do much in high school to let people know that I was even interested in music, besides playing in church. I went to Jacksonville Junior College in Jacksonville, Texas. I played a talent show there and people seemed to be into it. I put my guitar away for a while and didn’t write because I’m so one-track-minded that I couldn’t make my grades and write songs and play guitar at the same time. I thought I maybe wanted to be a pilot or an engineer. It was always in the back of my mind that I wanted to sing and write songs, but I didn’t understand that you can get a publishing deal and write songs for somebody else to record. I hadn’t gotten that far in the process.

When I went to Belmont [Kinney relocated to Nashville in 1994], I was thinking more about sitting at a console and recording, because I’m not a great guitar player. I play enough to sing my songs. I got here and I started meeting other people who wrote songs. I took publishing classes and I realized you can actually do this for a living. That’s when I started leaning toward it as a career. I was just doing it because I loved it and I got a little attention! It was fun. I wanted to be an artist, too, but there are too many talented singers here that can’t get it going and I didn’t want to fall into that, so I focused on writing.

When I graduated, I started plugging songs for a company out of San Antonio. I did that for a year and half. I didn’t get my first writing deal until 2001. Between 1997 and 2001, I drove a Coca-Cola truck and worked for a cell phone company to make ends meet. It allowed me to come to Music Row and do some writing with my buddies. One of them that I had gone to college with had gotten a publishing deal, so he could do demos and they were pitching his songs. I was able to keep my foot in that door until I signed my first deal and was able to quit my day job.

What was the music scene like in Nashville when you arrived?

It was rocking! Garth Brooks was there and country music was hotter than it had ever been. It was a money-making machine. They were signing all kinds of artists, a lot of songwriters had deals, and it seemed there weren’t any hard times at all, but then again, I was still in school, so I wasn’t in the middle of it. It was still somewhat hard to get in, but I got my internships, and nearly every act seemed to be doing good and selling millions of records. Around 1997 or 1998, it started slowing down. I remember people saying, “It’s about to make a turn. It’s going to be coming back to traditional pretty soon.” I think some of them are still saying that. It was a good time to come in. It’s still good times; sales are picking up for some artists. But I don’t think we’ll ever see it like the early ’90s again.

Has downloading affected country music the way it has affected other genres?

That has been part of the problem. It has affected a lot of people. One of my buddies had 6 million plays on Pandora and he got under $600 for all of those plays. There’s Pandora and downloading, and they’re starting to find ways to monitor that, but you still have the pirates and all of that stuff going on where they’re getting it for free, and legitimate companies are not paying what they should.

You toured after releasing your album. What did you learn from performing live and how have those lessons helped you as a songwriter?

I opened for Sara Evans, so her crowd was a little tamer. She played a lot of theaters, so there were a lot of women and the boyfriends of the girls that wanted to be there. I thought that it was going to be a disaster, because my music was more for the beer-drinking crowd with a weird sense of humor. I put songs on my record that nobody else wanted to cut because they were afraid to cut them, and rightfully so! In that situation I learned that you can’t judge the crowd and say, “They’re not going to like this.” You’ve got to throw it out there and see what happens. They like to have a good time. You can’t play ballad after ballad, and tearjerker after tearjerker, because people come there to escape their normal life and you don’t want to bring them down. So I tried to keep it upbeat, keep them laughing, and keep them feeling good.

When I write for other artists, I’m picturing them onstage and thinking, What is going to get the crowd into this? It’s not just the lyrics or the melody; sometimes it’s the production, so when I produce a demo that my publishing company is going to pitch to an artist, I think, What’s going to get the crowd fired up? What’s going to make the artist feel cool and look cool? That’s pretty much what I pulled from touring. What was good about being onstage is that I got to witness what worked and what didn’t, but at the same time, every artist is different. There are artists who can sing ballad after ballad, but they’re not singing to 18- to 25-year-olds who are drinking beer and wearing bikini tops. It’s probably an older crowd. If you’re writing for an artist who gets their sales from that audience, then you play it safer and you write deeper stuff. But when somebody’s drunk, they don’t want to get too deep.

At what point did you feel that you “got it” as a songwriter — that you understood the craft and had the material to take to audiences?

I’ve always had an idea, but in the past four years I feel more confident than I’ve ever felt. I feel like this is my time. Before, especially when I was in my artist deal, I was writing a lot of funny songs. People loved them, but nobody would record them because they were a little bit too quirky, and they were afraid that listeners would going to get tired of hearing them. I’ve dialed in a little bit more in the past four years. That’s a long time to wait, but I’ve hit and missed since 2001. I’ve been more consistent in dialing in what I want to say. I never really cared before. I just said, “Well, this sounds like a hit,” or “I’m just going to write my song and not worry about it.” Now it’s “What do these guys want?” I’ve buckled down more and I’ve grown a lot as a writer. They say that the best way to get good is to write with someone who’s better than you, and I’ve tried to do a lot of that and learn from them.

Your songs have positive, upbeat lyrics and melodies. Are you happy by nature, or are happy songs just more radio-friendly?

I’ve always been that way. Any time I’ve tried to write a “downer” song, it brought me down and I said, “Screw it, I just want to go home.” I like to have fun. I was raised around goofy people. Everybody was always cracking jokes and having a good time. We had our serious moments, but I always seemed to thrive a little bit more when I could laugh or get to rocking. I enjoyed Merle Haggard and all that stuff, I listen to that too, but I don’t want to listen to downer songs all the time. When I write, if I’m going to sit here for six or seven hours, I can't sit here depressed, trying to find out what this song needs.

“Outta My Head” was kind of a sad song, but it was still upbeat, it had some passion to it, and it was fun to write. As long as I’m having fun in the writing session, I think I write a better song, and that’s why I stick with those topics. I have my share of leaving songs and all that, but it’s rare that I ever write a song where I’m sitting at the house, on the couch and drinking, because I know that an artist is not going to want to self-loathe all the way through the song. Nobody wants to do that in front of a crowd unless it’s a killer song. If it’s a killer idea, I’ll do it because I get excited about it, but most of the time I like to keep it upbeat.

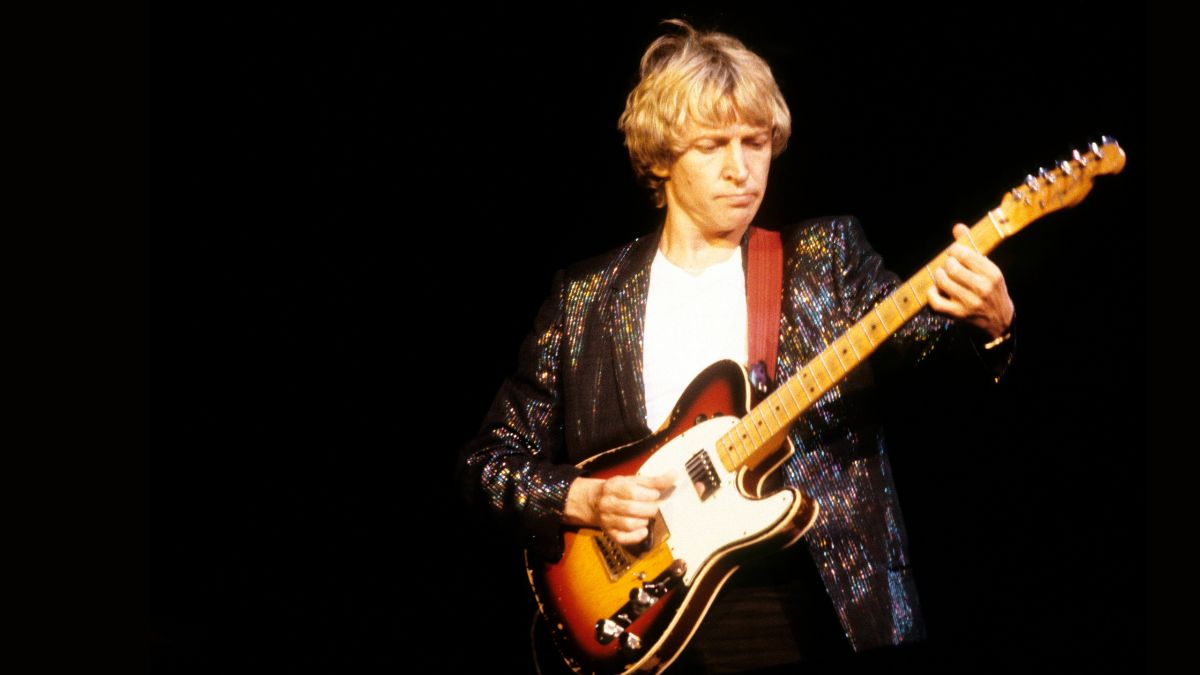

Photo: Stephen Gilbert

Read more of Brandon Kinney’s interview here

— Alison Richter

Alison Richter interviews artists, producers, engineers and other music industry professionals for print and online publications. Read more of her interviews right here.

Alison Richter is a seasoned journalist who interviews musicians, producers, engineers, and other industry professionals, and covers mental health issues for GuitarWorld.com. Writing credits include a wide range of publications, including GuitarWorld.com, MusicRadar.com, Bass Player, TNAG Connoisseur, Reverb, Music Industry News, Acoustic, Drummer, Guitar.com, Gearphoria, She Shreds, Guitar Girl, and Collectible Guitar.