Buzz Osborne: “Why does every metalhead who picks up an acoustic end up sounding like f**king James Taylor?!”

The Melvins' King Buzzo on his new acoustic album with Trevor Dunn, what he looks for in a bassist, and the key to his devastating live tone

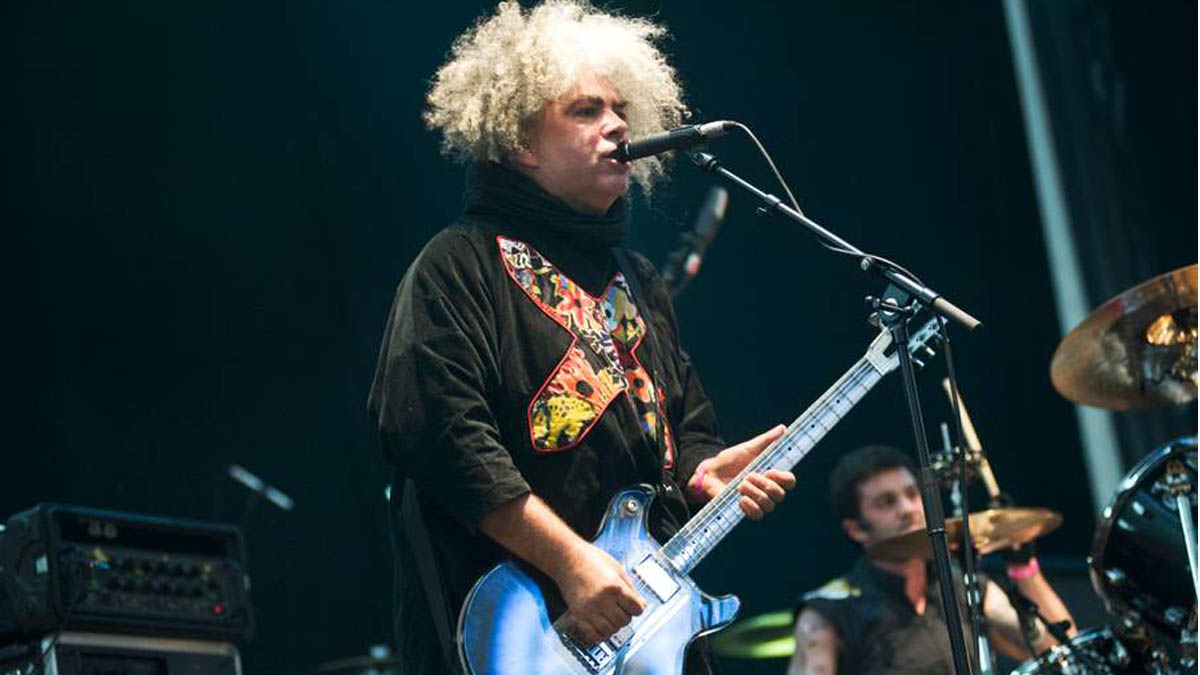

Buzz Osborne, aka King Buzzo, the indefatigable guitarist and vocalist of the Melvins, prolific, restlessly creative and hitherto a frequent flyer, is facing up to a year with no shows. And he's finding that pretty weird.

He has the record, Gift Of Sacrifice, out Friday (August 14) through Ipecac – an album of shifting moods, cinematic atmospheres, acoustic guitar, modular synth and Osborne's wry humor, recorded with bassist and long-term Melvins/Fantômas collaborator Trevor Dunn. There are just no shows where he can perform it. At least not yet.

“I’ve played live shows every year for at least 35 years,” he says. “We generally do 80 to 120 shows a year, so if I don’t do 80 shows this year that’s a really, really odd thing.”

As Osborne explains, this project with Trevor Dunn came out of plans to tour together, and one thing led to another. But even with the music industry in a fitful, enforced pause, it is inconceivable that Osborne will approach the act of making music and performing it any differently, that he will do anything but keep on keeping on.

You could adapt any of our songs and play them on the acoustic guitar, no trouble

In the broad-ranging conversation that follows, he assures us more music is in the pipeline, the Melvins will be animated in due course. He talks gear, tone and the interpersonal politics of collaboration, and the importance of a three-position toggle switch to his live sound.

But Gift Of Sacrifice being a predominantly acoustic album, so perhaps it's best to start there, and maybe we'll find out how Osborne can write unplugged and still maintain his edge where others have lost theirs.

What is the appeal of writing on acoustic? Is it the immediacy?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“No, more like a guitar is a guitar to me. Every guitar has different songs in it. I’ll write a different song on each guitar; every guitar I have, I play a little different. The guitar is different and that means the music in each of them is different.

"You never know what you are gonna get out of it. You could adapt any of our songs and play them on the acoustic guitar, no trouble. I have a little practice amp that I sit and play through, and I definitely write a different kind of thing than I would when I play through an acoustic, but by and large it doesn’t make a lot of difference. The thing that makes the biggest amount of difference is the tunings.”

What tunings are you using?

“A couple of tunings I came up with myself. And then lately, not just on this but on other things I have been writing, Open E and Open G tunings.”

It’s a good way of getting past the familiar and being led by the fingers.

“Yeah, it definitely puts you in a different perspective as far as, what you would automatically play doesn’t sound the same. And that’s cool.”

We often talk about the test of a good song being if it holds up on acoustic, but sometimes the acoustic can kill the song, because it brings out this outpouring of sentiment.

“Y’know, I haven’t had that trouble, but I have noticed exactly what you are saying. I always called it a James Taylor thing. Why does every metalhead or punk-rocker who picks up an acoustic end up sounding like fucking James Taylor?! It doesn’t make any sense to me. That’s okay. I generally don’t have any interest in those sorts of things so I have made a conscious effort to stay clear of it.”

How far along was the writing when Trevor came onboard?

“Well, it was over a year ago. I had most of the record written and recorded, and I had said that, in 2020, I planned on a big acoustic tour, a big tour of Europe, on acoustic, like I had done before, and I wanted him along. And he said that would be great, we’d go out and tour together, and at the very beginning it would be him playing and then me playing, and then maybe we would do a couple of things together.

Why does every metalhead or punk rocker who picks up an acoustic ends up sounding like f**king James Taylor!?

“I said, ‘Well why don’t you come out and we can record a few things and maybe put out a tour EP so we could have something to sell?’ He agreed, came out to LA, and I got the idea that, on this EP, I’d put on one of the songs that was going to be on the album anyway, so let’s have you play on this, and he did it, recorded it, and it came out really good.

“And I was like, ‘Well why don’t you try it on this other song? [Laughs] And why don’t you try it on this other song?’ And he just ended up playing on the vast majority of the record, which is why it is King Buzzo with Trevor Dunn rather than a King Buzzo/Trevor Dunn record – it’s because I had most of it done. But that’s how it happened.”

That's the best way...

“I’m kind of an accidentalist. I am not stupid enough to not take advantage of a good thing when I hear it, so I knew that his bass was adding a quality to it that wasn’t there and I had already wanted the combination of acoustic and modular synth.

The best kind of playing is playing that you don’t have to think about, you are on cruise control and zooming through it

"With the addition of the bass, my wife said that we had created something that she had never heard before… So that was cool! That’s really more than you can hope for.”

The atmosphere very cinematic. It’s got a Jonny Greenwood/PTA film score vibe. Was that the intention?

“The only thing I told Trevor was that I wanted him to overplay. Overplay on everything, with the idea that, if I told him to overplay, what I am really telling him is to play with as much freedom as he wants. I knew he wouldn’t overplay, but I wanted him to not feel like he was hindered at all, which is what I was really looking for. And he did it! It couldn’t have been better.”

What do you look for in a bassist?

“A fearlessness, a peculiarity that is more than just playing what the root note is. I am not afraid to trust musicians to do their work, and it has been my experience that if I approach songs that I have written with that attitude towards the musicians who are playing on them I end up with a better product. That’s it.

“I’ll be much happier with what I end up with than if I have tried to tell them exactly what to play – which, for most songwriters, that’s a mistake. It’s a mistake. They should probably adopt more of an attitude that you might not know everything, that these guys can make it better.”

The only thing I told Trevor was that I wanted him to overplay. Overplay on everything

The risk of thinking you know it all is you tend to miss the happy accidents, the good ideas.

“That’s it. It’s too bad. I have been in that situation before and it is not much fun. But that sort of stuff is arbitrary. I think it’s better. I don’t know if you do, but whatever. Too many people get hung up on this idea that, ‘I am the songwriter.’ Great, good for you! Should we call you maestro? Whatever!

"Or they get really, really defensive because they are worried about how they are going to split up the publishing. ‘Well if you write something, you might want money.’ So then we are really not working on music here, are we?”

The best artists never sweat that stuff, calling in the union if the bassist plays triangle on a section.

“I don’t like people telling me what to do, generally. There might be a few things with the bass player where I’d say, ‘Well that’s not exactly what we are playing. Here’s the real part.’ And I think they appreciate that, and they can build off of that.

“There's lots of stuff, especially with somebody like Steven McDonald who we play with now, that they are playing differently to what’s on the records and I do not care. It sounds great and I would rather just leave it. The records are merely suggestions of what could happen.”

Does it change your playing when you work with different bassists?

“Sure. Yeah, no doubt. A band is just that. It’s a band. I try to let things become something that is not already there. That’s the best thing. The best kind of playing is playing that you don’t have to think about, you are on cruise control and zooming through it, and it just feels like it is effortless and weightless. And the time just goes by, quickly!

"I always say the best shows I play are the shows I don’t remember. They were so effortless and I didn’t even have to think about it at all. And the ones I remember are the ones that I had to struggle, that I had to worry over, a lot, for whatever reason. That is never satisfying or fun but it happens.”

Tell us about the modular synth you have on the record.

“A buddy of mine from Atlanta helped me put it all together a few years ago, and I used everything that was on there. I don’t know the exact names – but I bought a case! And then I was like, ‘I wanna fill this case with stuff and then that is what I am going to use.’ I am not going to buy any more.

"There’s a whole bunch of different stuff – drums that you can completely terminate the sound in and turn it from one thing into another. The thing is, even if you take a picture of the exact settings, and the exact way that you wired it, it is never the same thing twice, so you can’t replicate stuff that you just did.

"You can come close to some degree but by and large it doesn’t really work, so you never know what you are going to get. If you have something good, you’d better be able to record it!”

That’s good though. It fits with your ethos. Just go with it, follow your nose…

“Well I have a few things with it that I will know that will work but it is never the same. It is always a new game, a new gamble, a new fun thing. That’s cool.”

What acoustics were you playing on the record?

“This record I was playing two Blueridge acoustics that I have. I used a Gibson acoustic that the engineer had, and I used a [Harmony F-70] Buck Owens American.”

Not to send you back through the memory hole, but a while back we put together a feature on the best metal guitar tones of all time, and we had Boris on it - can you remember how you got that tone?

“I don’t remember exactly but I think it might have been a [ProCo] Rat pedal through a Sunn Beta Lead amp, into a 4x12 and a 2x15 cabinet, probably mic’d close, closely on each speaker cabinet, and then I probably had a mic set up about six feet in front of it… Probably. Maybe a slight bit of delay on it.”

Are the 15-inch speaker cabs a standard part of your rig?

“Yeah, I’ve used those for a long time. Lately I have just been using Barefaced cabinets - a guy from Brighton [England] makes them, and I am using two bass cabinets for guitar. They both have two 12-inch speakers in them. But I might switch over to 2x12s and 2x15s again, maybe.

“I really like the Barefaced cabinets. I have been using Hilbish amps. Live, I am using the guitars from the Electrical Guitar company, some of them are Travis Bean hybrids – they’ll have wood and aluminum. And some will have a Plexiglas body and an aluminum neck.

“I also came up with two pedals with the Hilbish company. I came up with a Pessimiser pedal, which is a distortion box that also has a 3-band EQ in it, which is really rare, and a compression pedal.”

Your signal always sounds pretty dry. Have you ever been one for reverbs?

“Well you plug your guitar into any room and it’s gonna have reverb no matter what. Live, I’ll use a bit of delay on some stuff but not a huge amount. The Pessimiser distortion box, I’ll have on all the time, and the [Compressimiser] compressor I’ll switch on and off during the songs depending on how much go I want. Most of my sound comes from my guitar.”

Rolling the volume and tone back?

"I have my guitars, even the Travis Beans, set up like Les Pauls, which means that you have three different volume settings on the [pickup] switch. Three different volume settings on the switch means you have full blast, which is on the rear pickups, half-blast, or a little over half-blast, on both pickups.

"If I go just to the front pickup, it is a much lower sound, almost a clean sound, just with the switch you’ll have three different things right there, which is an enormous part of my playing – all because of how the Les Pauls are set up. The guitars I use live are always set up like Les Pauls. The switch is such an integral part of the way I play. I can’t get away from it."

We are a loud rock band; that’s what we do, and so I think that’s a big part of it. The drums are loud. The bass players always play loud, so I gotta keep up

Those dynamics are so wide. It’s onboard EQ and boost.

“Yeah, I’ll have it set up during a show so that the middle position will be loud without feedback, the high position to be as wild as it’s gonna get, and the other to be clean, so I don’t turn distortion boxes on and off during the show. I’ll leave them on. The only thing I am turning on and off is either the delay or the compressor, or I might have another effects box in there that I call the special effects box, which could be a wide variety of a bunch of different pedals that I’ll switch out.”

We all need a Friday night option on the pedalboard.

“Lately I’ve been using a Hilbish fuzz box. Sometimes I’ll use something called the Pitch Fork - the Electro-Harmonix Pitch Fork - and sometimes I will have a Blue Box [MXR Octave Fuzz] in there.”

How would you describe your relationship with volume?

“I still like playing loud guitar. It’s fun. I only really play loud guitar when we play live, or rehearse. That’s it. I don’t play loud guitar at home. That’s ridiculous. Also, if I am writing songs I am not playing some full-blast amp.

“The gear I have used over the years has changed a bit but my overall sensibility to it all hasn’t. We are a loud rock band; that’s what we do, and so I think that’s a big part of it. The drums are loud. The bass players always play loud, so I gotta keep up.”

You need that stage volume?

“It doesn’t bother me. Live, I don’t run stuff through the monitors. All I have in my monitors – no matter how big the stage is – is vocals. I don’t want drums in the monitor. We don’t have a drum stage, a drum riser, because I like to feel the drums through the stage.

“I like to have the drummer on the same level as I am at. I think it is much, much better to play that way, and so I have gotten to the point where I don’t need the drums in the monitor, or bass in the monitor. All I want is the vocals. I sure don’t need the guitar in the monitor.

Are you gonna screw the audience because the monitors are not right? Nobody cares. Do your job and stop being a baby

“Once you dumb your sound down that much and you get to the point where you can make that work – any situation that comes up, you’re gonna be okay. Somebody said to me, and I can’t remember who it was, a long, long, long time ago, when I was first starting to play, 'If you are going to play live, you are going to have to learn to listen.' That’s it. And the meaning is: don’t rely on the monitors.

“If you are relying on that stuff, at some point, some day, it’s all going to go to shit and then what are you going to do? Quit? You still have to play the show. It doesn’t make any difference. Are you gonna screw the audience because the monitors are not right? Nobody cares. Do your job and stop being a baby.”

Right. And you can't underplay the importance of the ability to listen.

“Yeah, and if you are really having trouble just turn around and look. You can see those guys playing – I never have any trouble hearing them. And our drummer, our drummer plays fantastically loud. 'You want kick and snare in the monitors?’ No! A lot of monitor engineers can’t believe it. All I want is the three vocals. ‘And kick and snare?’ No!

“Monitor engineers are used to people being pissy. I heard about this really prominent band, where the drummer wanted this massive drum mix, all changing for every fucking song. ‘Bring the bass up here. Bring it up for the solo here.’ What are you talking about!? Are you really going to let your performance rely on something so ridiculous. Learn to listen. Play with these guys. That’s all you have to do.”

Presumably, you’ve got heaps of music in the pipeline. If it all goes to shit and you don’t have tours, will you keep writing?

“I record stuff all the time, demo ideas, various things, but beyond that we have lots of stuff in the works, so it’s all good.”

Going back to Gift Of Sacrifice. It is inherently cinematic. Now, you’ve contributed the odd song here and there to movie soundtracks. Would you do a whole score?

“I would be hesitant but I wouldn’t be completely against it. We did a record a few years ago called A Walk With Love And Death, a double album, and one of the albums was more of a regular Melvins album and the other was a soundtrack for a movie that didn’t exist.

“We just made a soundtrack like we were making a soundtrack for a movie. Then, me and this buddy of mine from Atlanta, cut it down to 33 minutes after we put the record out, and made a movie to go along with the soundtrack.”

Why would you be hesitant?

“I’m not sure how well I would do with someone telling me what they wanted and what they didn’t want. I’m not good at going out there and selling myself to these people. We’ve written and recorded more than 500 songs. You really can’t just find something in there?”

- King Buzzo with Trevor Dunn's Gift Of Sacrifice is out August 14th, available to pre-order now.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to publications including Guitar World, MusicRadar and Total Guitar. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.