“I tried it fingerstyle, and that didn't work. As a joke, somebody said, ‘Why don't you try slap bass?’ Everyone was laughing. Then we went back and listened to it…” Chris Wolstenholme switched up his tone and technique on Muse’s The Resistance

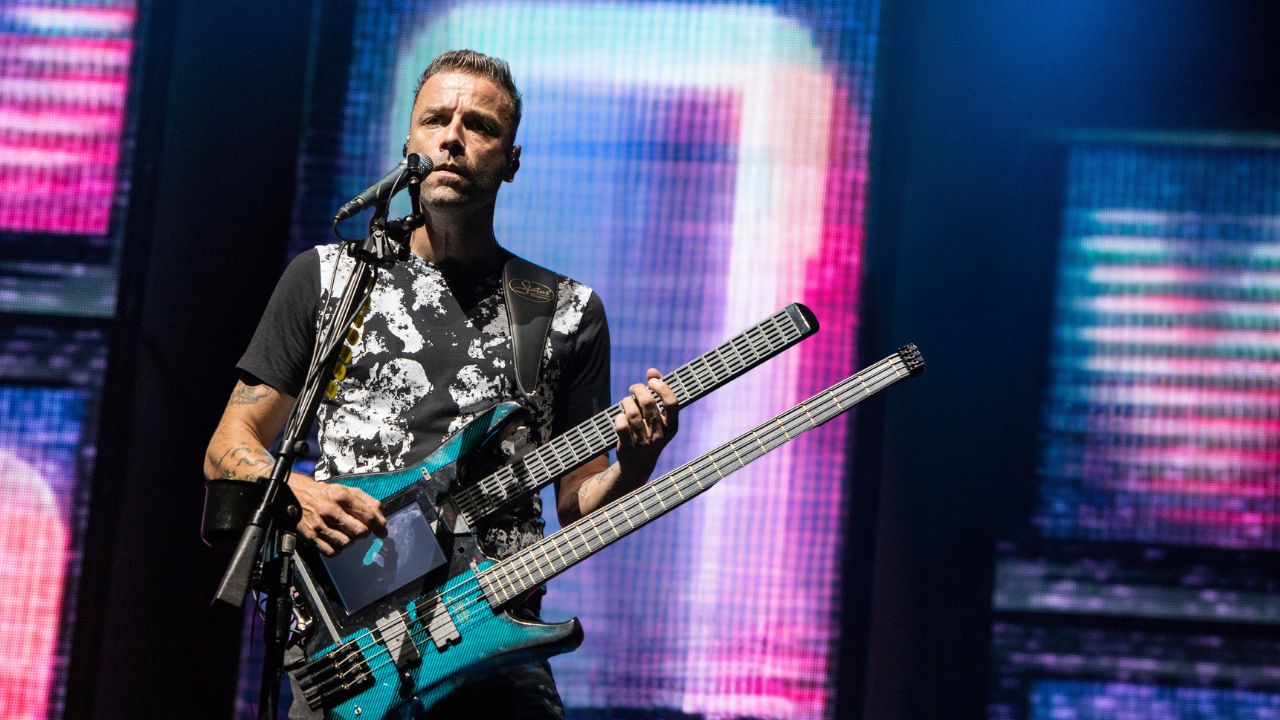

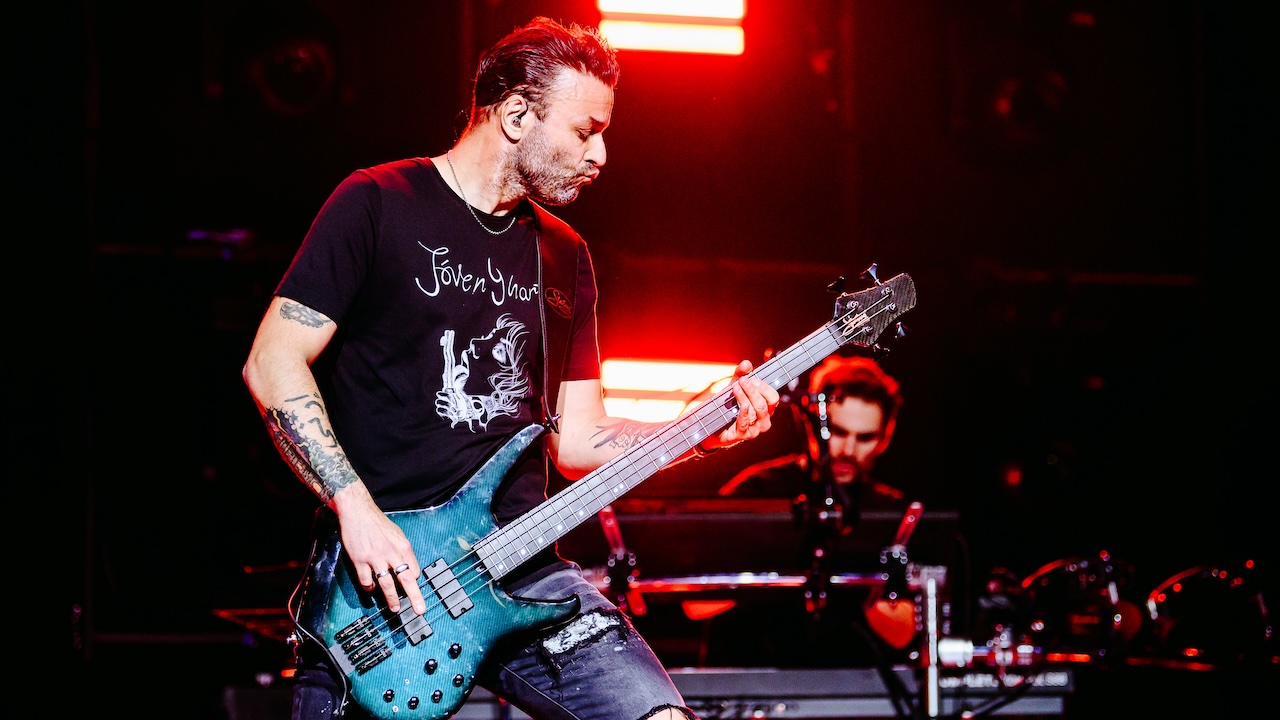

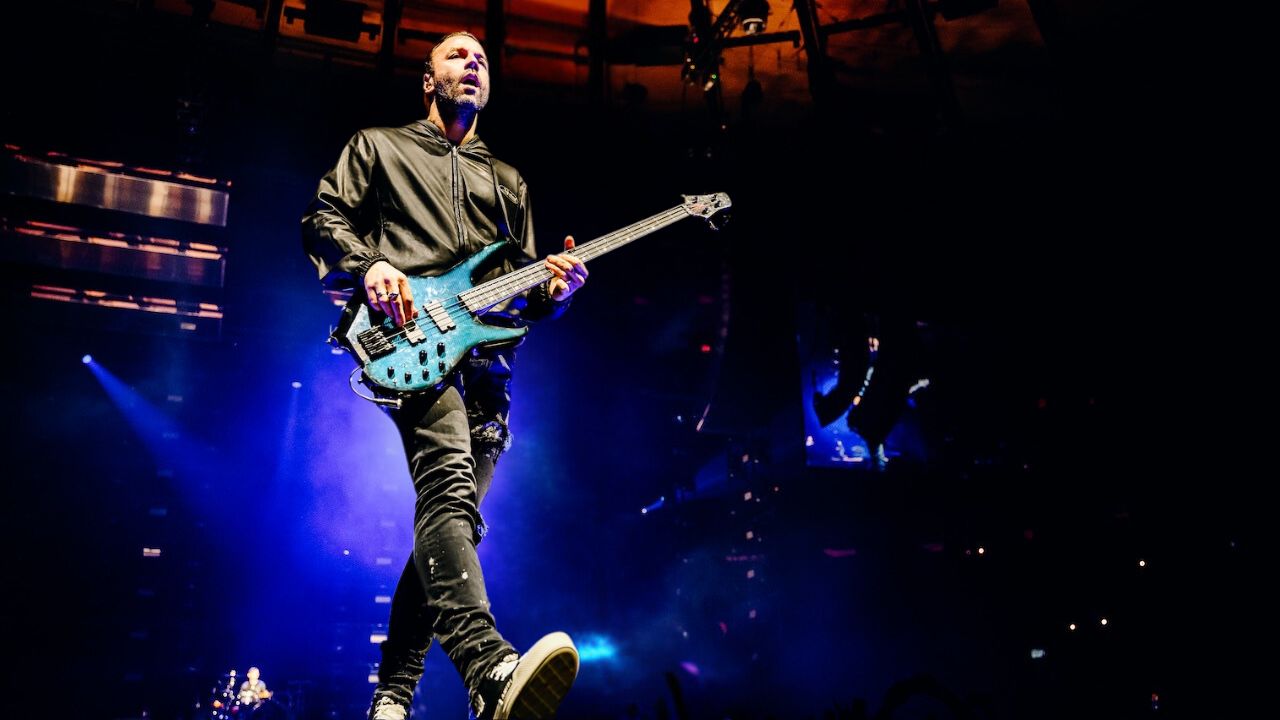

Monstrous tones (and a massive signal chain) are just part of Chris Wolstenholme’s bass evolution with Muse

Since forming in 1994, Muse have gone on to scour the heights of rock stardom. Fusing everything from rock, prog, indie, classical and electronica, the trio of Matt Bellamy, Chris Wolstenholme and Dominic Howard create a musical landscape that’s daring, complex, sophisticated and exciting, delivered in a way that remains accessible to us all.

Since starting out, bassist Chris Wolstenholme has taken to the stage with a host of different basses including a Warwick, a Pedulla Rapture, a Zon Sonus, a Fender Jazz and a Rickenbacker 4003. Yet Muse’s 2006 release, The Resistance, featured the biggest variety of basses he’d ever used to record an album.

“I think I used a different bass on every track!” Wolstenholme told Bass Player. “I bought an old ’73 Jazz Bass that I used and I’ve got this embarrassing ‘80s Status headless bass that looks awful but sounds brilliant, so I used that on a couple of tracks as well.

“I also used my Pedulla on a few tracks and I played a few Gibson basses, like the Gibson Grabber and a Gibson Ripper. The songs on that album are so varied that it kind of required a different tone for each track.”

Amp-wise, Wolstenholme was still an avid user of Marshall amps, but in the studio he mixed things up a little more.

“For most of the clean bass sounds I actually used an Ampeg SVT Vintage reissue. I’ve always felt that Marshalls are great for the really heavy stuff, very consistent, and obviously live they are great. But in the studio I wanted to have something with a little more character to it.

“I used the Ampeg for a few songs and an old ‘70s Orange bass head as well. I’ve got so much going through my amps with octavers and distortion pedals that they take a real hammering and you need something that can stand up to it.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

As for the rest of his signal chain, he explained: “A lot depends on what Matt is doing. You don't want the guitars and the distortion of the bass to become one. You want them to be separate. And that's a very hard thing to do, because you need a bass pedal that doesn't work in the same frequencies as the guitar.”

“Sometimes you hear a great bass sound… and then as soon as the guitar comes in, it's kind of swallowed up. The important thing is to make sure those guitar frequencies don't clash, and that they both stand up in their own way.”

“Matt has a lot of weird stuff going on as well – he's got four different heads and several different distortion pedals, all of which sound completely different. So I'll try a number of different pedals, and work out which one fits better where you can still hear it amongst the guitars.”

In pulling it off live, how does Wolstenholme keep up? “My bass tech does it all live now, which is great because a lot of the time I'm singing as well. So it's nice to not worry about that side of things; there are so many pedal changes, I kind of found myself tied to the pedalboard the whole gig.”

After so many years at the low-end, what wisdom does Wolstenholme have to offer the world of bass? “Listen to as many types of music as you can. A lot of people pigeonhole the bass, particularly in rock music, but there's a lot to learn about basslines from things like classical music and jazz.

“You don't have to be a total geek about it – it's just nice to acknowledge things outside of your comfort zone, because if you want to improve as a musician in general, you need to be educated by different types of music. There's only so much you can learn from listening to rock bands.”

We asked Wolstenholme to name his favorite bass tones from The Resistance.

Uprising

“That song was influenced quite a lot by British electronica. We wanted to create that kind of synth-y sound, without using synthesizers. With a lot of basslines in the past, we combined distorted basses with synths to create a new-sounding thing, but we made a decision that the rhythm section had to be real, so we came up with a bass sound that almost sounded like a synth, but wasn’t.”

Unnatural Selection

“We just wanted it to be fat as fuck! Even though it's a heavy track, when you strip it back to the guitars themselves, they're not really overdriven. They're sort of more crunchy. So we knew that the power of that song had to come from the bass. It was a case of just switching all the amps on, and switching both Big Muff pedals on, and both Animatos, and seeing what came out of it.”

Wolstenholme tunes down not just the E string (to D) but also the A to G for a rocking unison riff that flies off the fingers once you get the hang of the open G.

“I think I originally played it with just the drop D, but I like to play riffs like that with open strings as much as possible. I get a much nicer sustain doing that, rather than struggling higher up the fingerboard. So I tuned the A to G and the E to D. And you suddenly realize it's a hell of a lot easier to play.”

Undisclosed Desires

“Because we were going more R&B, we thought we'd go for a real chubby, plectrum-y bass sound. So we tried that and it didn't work. I tried playing it fingerstyle, and that didn't work. And then just as a joke, somebody said, ‘Why don't you just try playing slap bass?’ So I did.

“Initially everyone was laughing their asses off. Then we went back and listened to it, and we thought, ‘If we make the sound edgy enough, it could actually sound cool.’ So we put a Hematoma pedal on it. I had a slight, top-endy distortion to crunch it up a little. The danger with slap bass is if you go for that super-clean, twangy bass sound, it ends up sounding like Level 42. So we just dirtied it up.”

I Belong To You

“The wah/synth is actually an acoustic/electric bass with the Akai Deep Impact pedal. We took a DI from it, and we mic’d it as well. I think that song had a kind of comical sound to it, and we wanted to push that a bit further.

“We tried loads of stuff, and we tried electric basses with synth pedals, and nothing seemed to sit right with the piano. So we had this cheap, semi-acoustic bass that was just sitting around the studio. I'd not played it for years. It sounded quite unusual, because you don't associate acoustic/ electric basses with synths.”

Nick Wells was the Editor of Bass Guitar magazine from 2009 to 2011, before making strides into the world of Artist Relations with Sheldon Dingwall and Dingwall Guitars. He's also the producer of bass-centric documentaries, Walking the Changes and Beneath the Bassline, as well as Production Manager and Artist Liaison for ScottsBassLessons. In his free time, you'll find him jumping around his bedroom to Kool & The Gang while hammering the life out of his P-Bass.