Dave Grohl: ”We were doing the things we’re not supposed to do. The galloping flange guitar... the Abba beat!”

Early-'80s David Bowie, Eye of the Tiger, single coils? Here's how the Foo Fighters got “weird” for Medicine at Midnight

“It was the Foo Fighters’ 25th anniversary, so it was going to be a big year,” Dave Grohl says. “We thought, it’d be great to make an album, our 10th studio album, and I started planning around that – ‘Let’s circle the planet!

“Let’s release this documentary thing that we’ve made! Let’s do these van tours! We’ll play the same cities 25 years to the date that we did on our first-ever tour… and in the same van we did the tour in!’ Just all this shit, you know? Basically coming up with this world-domination-celebration thing.”

Spoiler alert: 2020 did not work out the way anyone – Grohl and the Foo Fighters included – had planned. Which is why the singer and guitarist, rather than telling this story to Guitar World from the back of a beat-up van in some far-flung locale (that van tour, scheduled to begin last April, was cancelled as the world went into COVID-19 shutdown) is, like everyone else, at home, talking about his aborted world domination plot over – what else? – Zoom.

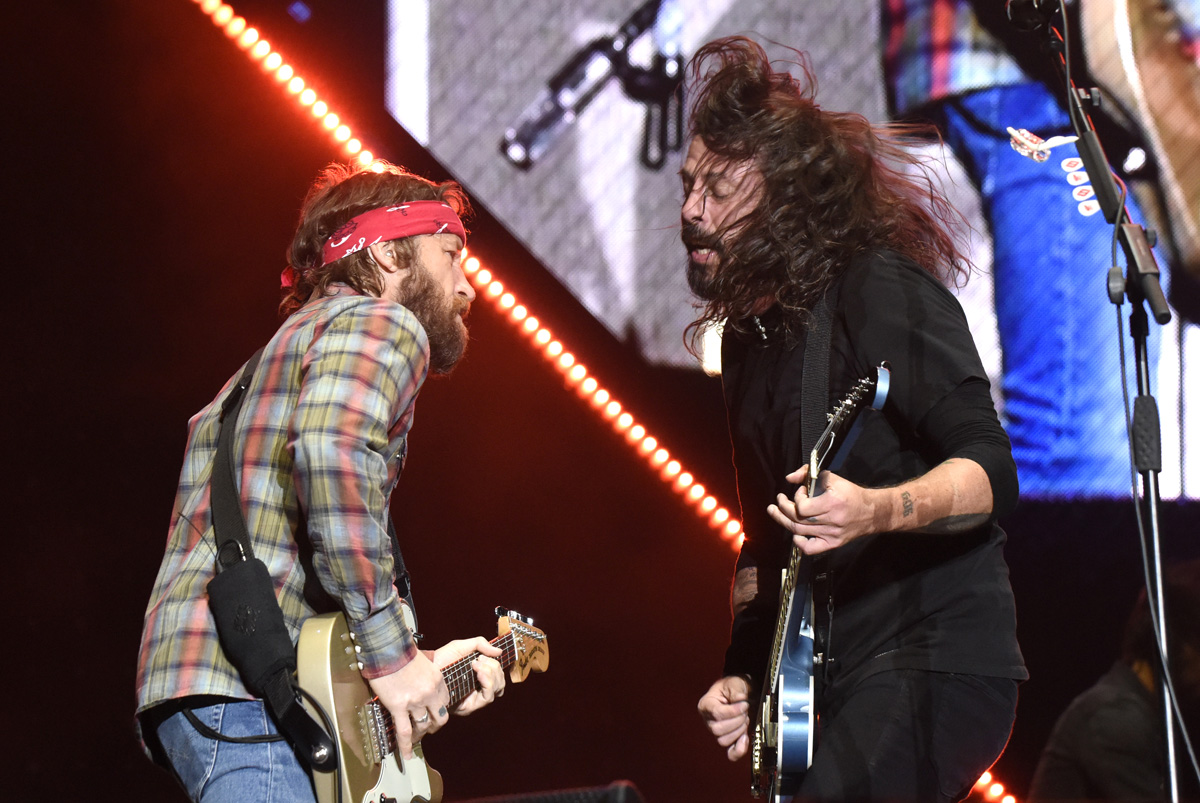

And when our narrative is enriched with brand new anecdotes courtesy of Dave’s Foo Fighters co-guitarist, Chris Shiflett? That interview takes place over Zoom as well, with Shiflett safely confined in his home.

The final piece of the Foos guitar triumvirate, Pat Smear, meanwhile, is clearly not taking any chances. He speaks with GW via a crackly cellphone connection from the east coast of Canada, where he’s holed up, he reports, “in the snow in a little cabin deep in the woods, with no mail delivery or garbage pickup.”

“He’s turned into a Canadian frontiersman,” Shiflett says with a laugh. 2020, to say the least, was weird. But while the Foos didn’t get to spend the year circling the planet delighting fans, they did manage to get some real work done.

For starters, Grohl finished his documentary, What Drives Us, which finds him exploring the psychology behind why musicians drop everything to spend their lives traveling in, yes, a van, to bring their music to people. And the Foo Fighters – which is rounded out by drummer Taylor Hawkins, bassist Nate Mendel and keyboardist Rami Jaffee – recorded that celebratory 10th studio album.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

It’s called Medicine at Midnight, and it’s a killer. It’s also unlike anything you’ve heard from the band before. Sure, there are all the Foos trademarks – indelible riff-rockers (Cloudspotter, Holding Poison), tightly coiled ragers (No Son of Mine), soaring ballads (Waiting on a War) and hooks (Making a Fire) upon hooks (Medicine at Midnight) upon hooks (Love Dies Young).

But there’s also something else going on: an adherence to groove and atmosphere – and a very particular sort of early-'80s-pop-rock-new-wave-dance groove and atmosphere – that lays out a fresh sonic and stylistic launching pad for these songs.

I wanted to be sure we didn’t make Learn to Fly again. Or Best of You again. Or My Hero again. We’ve done those already. If we want to be a band for another 25 years, then we have to be able to find something new

Dave Grohl

You hear it in the slinky, heavily syncopated rhythms of the album’s first single, Shame Shame, and you hear it even more in the bubbly, synthy riffs that power Love Dies Young.

And you hear it maybe the most in the sultry, heated funk of the title track, which nods heavily to David Bowie’s 1983 pop-exotica classic Let’s Dance in sound and style – and even the guitar solo, which finds Shiflett paying tribute to Stevie Ray Vaughan’s bluesy work in the Bowie original.

“I’m sort of aping Albert King through the lens of Stevie Ray,” Shiflett says of his lead work on Medicine at Midnight. “I even said to our producer, Greg Kurstin, ‘We might want to mix these licks up a bit, because it’s really a homage.”

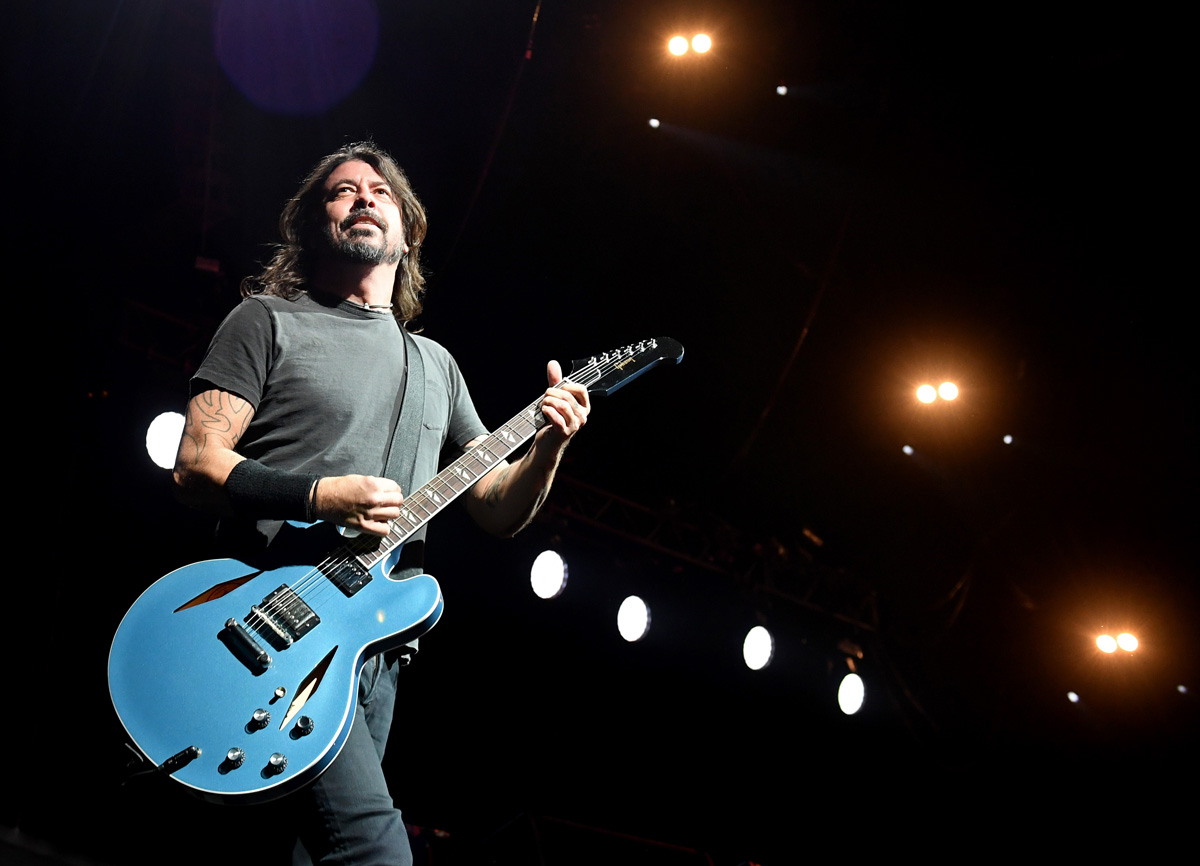

He laughs. “But, hey, that’s rock ‘n’ roll!” Shiflett approached the Medicine at Midnight solo not only from a unique perspective playing-wise, but also in his choice of guitar.

“The Foo Fighters are generally a humbucker kind of group,” he says. “I remember a few years ago I showed up at something we were doing with a Strat and Dave looked at me and said, ‘Now there’s something I never thought I’d see in my band!’

“Because we don’t really do the single-coil thing. But for Medicine at Midnight’ that’s where we wanted to go. So I grabbed one of my Strats and worked out the solo stuff and it was really fun. And I love that about our band – that we still have these moments of getting to jump into things we’ve never tried before.”

Grohl lays it out in more general terms. “After 25 years, and now we’re making our 10th record, I wanted to be sure we didn’t make Learn to Fly again. Or Best of You again. Or My Hero again. We’ve done those already. If we want to be a band for another 25 years, then we have to be able to find something new. So the greatest reference I had for this record was everything we’ve done in the past. And it was, ‘Let’s not do that.’”

Or, as Smear puts it, “We just said, ‘Fuck it, let’s get weird on this one.’”

That weirdness began, in a way, much like past Foo Fighters records have begun – although that process is somewhat weird in and of itself. After coming off a 16-month world tour in support of their 2017 album, Concrete and Gold, the idea was, as it often is with the Foo Fighters, to take a break.

“We kind of work this cycle where we’ll go into the studio and make a record, then we run around playing clubs and doing promo for a couple of months, and then we release the record and tour for a year and a half,” Grohl says. “By the time we’re finished with that cycle, we’re all exhausted and we promise ourselves we’ll never put each other through that fucking hell ever again.”

He laughs. “I say it every fucking time. You should ask my wife. She’s like, ‘I hear it every time – I’m exhausted. I’m never doing this again. This is the last record, blah, blah, blah.’”

“We always claim we’re going to take this break and then… we miss it,” Smear says. “We miss each other, we miss making music together.”

“So within two and a half weeks, I’m demoing shit and sending it to the band,” Grohl continues. Smear concurs. “It’s never more than a few months after we’re home that we’ll get a group text from Dave saying, ‘Hey, I’ve been writing songs…’ Then it’s on.”

The Foos began recording Medicine at Midnight before the pandemic hit. But whereas in the past they’ve tracked at various facilities, including the band’s own Studio 606 and, for Concrete and Gold, EastWest, located in the heart of Hollywood, this time they took a different approach, taking up residence in a 1940s-era home in Encino, California, not far from Grohl’s own house.

“The weird thing is, I actually lived in that house 10 years ago,” Grohl says. “I was going through a remodel at the time and needed a place close by to move into while my house was completely bulldozed. This place looks kind of like an old mansion, with these big iron gates out front.

“It sounds beautiful, but really it’s a dilapidated, rundown, spooky old house in the middle of Encino. Amazing neighborhood, though – you can jump some fences and go be in Slash’s yard, or walk six houses up and there’s Steve Vai’s place. Within, like, 75 yards, there’s all this guitar-hero wizardry. It’s insane.”

As for how the non-traditional environment affected the recording process, Shiflett says, “it was a really different vibe than Concrete and Gold. That record was made at a beautiful, classic studio with multiple rooms, so you have that thing where, you know, one day you walk in and Lady Gaga is sitting on the couch in the lounge or whatever.

“But this time, because you’re in a house, you remove all the sort of Hollywood entertainment elements of it. Which was great. You’d show up in the morning and, depending on where we were in the recording process, you might be working or you might just be hanging out in the kitchen, drinking coffee and shooting the shit. It was real laid back.”

But if the band members themselves were relaxed, the house itself had a fair amount of activity happening. “I started demoing things there by myself around June of 2019, and it felt creepy,” Grohl says. “But I thought, well, you can creep yourself out if you’re alone in an old house at night recording rock songs.

“But then as we moved in, weird little things would happen here and there, whether it was guitars being detuned, settings moving around on the board or shit happening in the Pro Tools session that wasn’t supposed to happen.”

“It was a bit of an oddball house,” Shiflett acknowledges. “It has that look that’s sort of like it’s being reclaimed by the mountainside, and everything’s cracked and the pool is nasty and there’s vines everywhere. It had a vibe.”

“Beyond that, there was this feeling that you were either being followed or being watched all the time,” Grohl goes on. “And when more than one person is feeling that way but they don’t tell each other, and then all of a sudden everyone starts confessing, ‘Oh, this room in the house? This room is fucked up.’ Or, ‘That stairway? That stairway’s fucked up.’ When it all starts coming out you’re just like, ‘Oh my God…’”

Even Smear, who asserts that he “doesn’t really believe in magic and that kind of stuff,” admits, when pressed, that “there was a lot of odd and creepy goings-on happening.”

We intended on making a record that was short and sweet, because it’s inspired by a certain type of album that we all loved when we were young. Like an '80s Bowie record – tight, full of grooves, lots of melodies

Dave Grohl

“So we recorded nine songs and got the fuck outta there!” Grohl says with a laugh. In fact, at just nine songs and 37 minutes, Medicine at Midnight is the Foo Fighters’ most concise full-length to date. But not because they were trying to flee from supernatural forces.

Rather, Grohl says, “we intended on making a record that was short and sweet, because it’s inspired by a certain type of album that we all loved when we were young. Like an '80s Bowie record – tight, full of grooves, lots of melodies, that’s it. Let’s go.”

While the band ultimately traveled a very specific stylistic road, that intention wasn’t set in stone right from the beginning. “There were a few things that got recorded that didn’t see the light of day,” Shiflett confirms.

“It was a bunch of songs and they were all great and they were all very ‘Foo Fighters,’” Smear says. But then, he continues, “we did Shame Shame, and that just changed the direction of the whole process.”

Indeed, Shame Shame, built on a stark, repeating five-note figure that is adorned with handclaps, keyboard accents and other sonic ephemera, is among the biggest stylistic departures on Medicine at Midnight, and maybe even within the entire Foo Fighters catalog.

“It was the first left turn,” Grohl says. “And it’s such a simple riff. When I did the demo I had that rhythm, and then I overdubbed this hand-clapping thing over it. Then we put the drums in a stairway, which sounded so fucking killer. Did more overdubs.

”Now all of a sudden it was a groove that we had never done before. And not only that, it had this tone and dynamic that we had never really gotten into. That really inspired us to start loosening the reins and just let shit fucking happen.”

This change in attitude and approach resulted in songs such as the closing track, Love Dies Young, which, according to Grohl, started out as a “strummy sort of song we’ve done a million times.” But that’s not where it wound up.

“Taylor [Hawkins] was like, ‘What drum beat should we do? How about a 16th-note thing?’” Grohl recalls. “And I went, ‘Fuck that! What about an Abba side-high-hat-disco thing? We’ve never messed with that before!’ And then the guitar riff turned into a Keep Yourself Alive type of thing.”

Of course, one man’s Queen is another man’s… um, Survivor? “The galloping rhythm part that I did in that song, it’s like Eye of the Tiger, ” Shiflett says, bringing the musical references back around to the early Eighties. “It was almost like a joke. But we listened back to it and we were like, ‘Hmm… that actually sounds pretty good!’”

That wasn’t the only Eighties guitar reference Shiflett brought to the song. “I was also hearing General Public,” he says. “You remember the guitar sound in Tenderness? That twang? Well, I went for that same sort of Gretsch-y thing.”

We were just sitting on the couch laughing because we’re doing the things we’re not supposed to do. At the end of the day, we had something we’d never done before

Dave Grohl

“Each instrument we put on, we were just sitting on the couch laughing because we’re doing the things we’re not supposed to do,” Grohl says. “We’re not supposed to do the galloping flange guitar! We’re not supposed to do the Abba beat! But we’re just like, ‘Fuck, load it up, man!’ And then at the end of the day, we had something we’d never done before.”

But no matter where a song ultimately ended up, for Grohl it generally always started in the same place – with the rhythm. “I basically wrote all of these songs on an acoustic guitar,” he says. “As a drummer, when you’re jamming with someone, you watch their hand and the accent of the way they strum their guitar.

“And what I do is I base the groove on the way a person strums a guitar – if the ‘up’ is harder than the ‘down,’ if the ‘down’ is harder than the ‘up,’ if there’s focus on the lower strings… I don’t read music so I don’t know the proper terms for any of this shit, but I watch someone’s feel on the guitar and I base what I’m doing on the drums from that.

“So if I’m sitting on the couch doing this whole thing by myself,” he continues, “I’m already clicking my teeth when I’m playing and I know, ‘Okay, here’s the groove of the song and here’s the accent. And this is the feel.’ So a lot of the songs began with a specific feel more than a specific riff. It’d start with a kind of rhythmic foundation and then I’d go from there.”

Screaming bloody murder and playing as many notes as you can, that’s fun. But to me, the complicated puzzle of braiding those things together in a way that seems simple is the greatest challenge

Dave Grohl

As for that other key component of the Foo Fighters sound – the melody? “To me, that’s the most important part of a song,” Grohl says. “And that comes from growing up with Beatles records and sitting down with a chord book, trying to understand why those harmonies do what they do and why the melody moves the way it does and why the composition and arrangement is like this.

“That’s the Rubik’s Cube, right? Screaming bloody murder and playing as many notes as you can, that’s fun. But to me, the complicated puzzle of braiding those things together in a way that seems simple is the greatest challenge. It’s like, ‘Okay, great, I’ve got a groove – that’s cool. I’ve got riffs – that’s cool. But none of it’s going to work unless there’s a fucking melody.’ And then you realize nobody’s going to care about any of it unless you’ve got a lyric. So now you add your words. It’s like baking a cake backwards.”

To continue a metaphor, that cake also requires a few additional ingredients – chief among them, gear. And on Medicine at Midnight, the guys used a lot of gear. “As is usually the case with making a Foo Fighters record, everybody brings in their special stuff,” Shiflett says. “So we had a room full of our favorite guitars and everybody’s favorite amps.”

In Shiflett’s case, that meant several Master Built versions of his signature Fender Telecaster Deluxe, as well as various Strats and Teles and a ’57 Les Paul Gold Top with “old PAFs.” Amplifiers, he says, included a vintage tweed Fender Champ and Vibrolux, the latter loaded with a Celestion Greenback speaker, as well as a recent hand-wired Vox AC15 that he calls his “magic, go-to” amp.

I’d be lying if I tried to say what amp went on what song, because you’re just kind of putting stuff together and trying different sounds

Chris Shiflett

“And then one of our crew dudes brought some old Marshalls, an old Park head,” Shiflett adds. “And there was also some really weird stuff that I wasn’t even familiar with, like a kooky, regional amp that was made for harmonica players.

“I’d be lying if I tried to say what amp went on what song, because you’re just kind of putting stuff together and trying different sounds and trying to add to things that are on the track already,” he continues. “A big part of it is just finding something that sits where it needs to sit. And that’s going to be through combinations of different guitars, different amps, different pedals. Like, I remember we used Greg’s old space echo a lot, which I loved. It was like instant Clash when you plugged that in.”

Adds Grohl, “There was a bedroom full of these things and it just came down to us deciding where we wanted to go sonically. And then we would blend different amps together – my guitar tech, Ali, brought in a lot of cool shit that we had over at [Studio] 606.

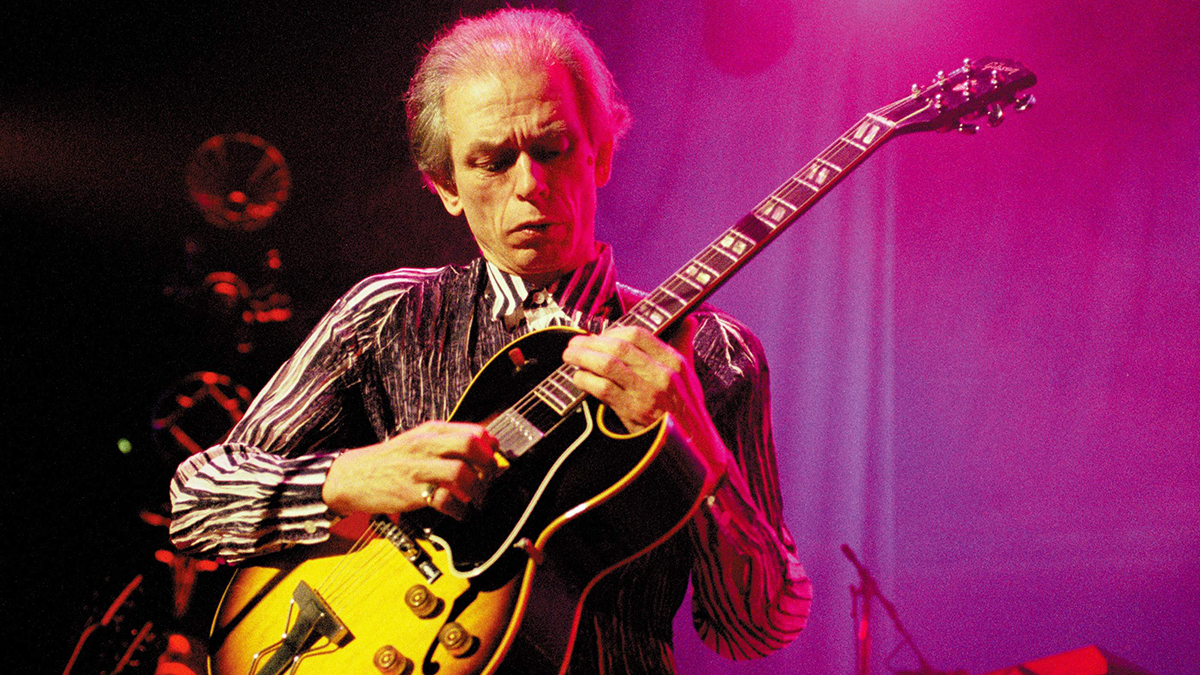

“As for guitars, for the most part I relied on my Trinis [his Gibson Trini Lopez models] – I had my number one, which is an old red one, and then a Pelham Blue one. I prefer Trinis because I feel they’re more dynamic than most guitars.

“And a lot of it has to do with that tailpiece that almost rings like a snare – it gives the guitar a percussive element that, depending on what you do with your hands, you can bring it up and down almost as if it were a drum.”

For the most part I relied on my Trinis. I prefer Trinis because I feel they’re more dynamic than most guitars. And a lot of it has to do with that tailpiece that almost rings like a snare

Dave Grohl

He continues, “But, you know, I also had an old ’73 Tele that I was using. Because it’s all just a process – ‘How do you hear the sound? What do you think it should be?’ And you say, ‘I think I need something that cuts, and has a little top end to it.’ Okay, cool. My tech runs off, he comes back, puts the Tele in my lap and we’re off.”

As for Smear? “I tended to just play whatever guitar I felt like playing that day,” he says simply. “Pat collects guitars – don’t be fooled!” Grohl says with a laugh. “That dude has hundreds of fucking guitars!”

Indeed, Smear acknowledges that he’s “more of a guitar guy than I am an amp guy, so I kind of don’t really pay attention too much to amps. I’ll say, ‘Oh, I like the way this guitar sounds with that amp. By the way… what was that amp?’”

Nobody’s a real technical diva in this band. We still operate on the level of, like, a weekend fucking keg party band

Dave Grohl

As far as his guitars on Medicine at Midnight, Smear will at least acknowledge that there was a “wobbly” Gibson SG in the mix. “You know how SGs can have a tendency to be very wobbly?” he asks. “Well, I have this one SG that’s particularly wobbly, and I put light strings on so it would be extra, super-wobbly.

“I remember putting that on a couple of things because I wanted that warble. But other than that, it was just, ‘I feel like using this here.’ Or somebody would say, ‘Hey, play something with P-90s there.’ We’re not that organized, it’s just kind of, ‘That’s right there. Let’s use it.’”

At the end of the day, all three guitarists affirm it’s all about just getting a good sound and then going for it.

“Nobody’s a real technical diva in this band,” Grohl says. “To this day, we’re perfectly comfortable just grabbing a bunch of combos and putting them in the back of a truck and taking them to a pizza place and plugging them in and playing. We still operate on the level of, like, a weekend fucking keg party band.”

That said, in 2020 there were, of course, no weekend keg parties – or, for that matter, 50,000-fan-strong stadium rock spectacles – to be had. Which certainly put a dent in the Foo Fighters’ plans as far as releasing and touring behind what Smear characterizes as a “happy, fun party record.”

Says Grohl, “As time went by, I wondered not only when, but how we would release the album, knowing that a big part of the Foo Fighters world, the touring and the shows, was taken away.” And in fact, Medicine at Midnight was delayed from its original release date, which was scheduled earlier in 2020.

“Everything ground to a halt,” Shiflett says, “and plans kept getting pushed further and further back. But then at a certain point I remember Dave just kind of putting his foot down and saying, ‘No, we have to get this record out and start doing stuff.’”

“I was like, ‘Okay… I guess we’re just going to release a new record,’” Grohl says. “Because it became clear that there was no use waiting for things to go back to normal. It just wasn’t going to happen anytime soon.”

Interestingly, after an extended period apart (“I went seven months without seeing Taylor Hawkins – that has just never happened in 20-whatever years!” Grohl says with mock outrage), when the band got back together, “we were really learning the new songs for the first time,” Shiflett says. “Because we didn’t do any pre-production or anything going into the record. But it was cool to come back to it with fresh ears and be like, ‘It still sounds really good!’”

That said, adds Smear, “From the first rehearsals for the livestream show [in November the Foo Fighters performed a benefit concert, sans audience, from the Roxy Theatre in Hollywood], it was immediately ‘home.’ And I’ll tell you, even the livestream – which, before we did it, it seemed like, ‘Oh, this is so weird, we’re gonna play a concert for roadies and cameramen?’ – I can’t tell you what a fun show it was. I don’t remember the last time I had that much fun playing!”

Despite how much they enjoyed jumping around on a stage for a few cameramen and roadies, the Foos are steadfast in their determination to eventually bring Medicine at Midnight’s considerable grooves to life onstage, in front of thousands of sweaty, dancing fans.

“As soon as we get the green light, we’ll hit it,” Shiflett says. Until then? Well, the idea of unleashing a “party” record during a pandemic maybe isn’t as incongruous as it might sound.

“To be honest, one of the things that really inspired me was this drum battle that I was having with this 10-year-old girl in England [Grohl and the 10-year-old, Nandi Bushell, struck up a competitive friendship that went viral on social media],” he says.

“What I realized during this funny exchange, which we were posting online, was that it was making people happy in a time when you open up your computer and you’re just waiting for the bad news. Or you pick up your phone and someone’s texting you and you’re just waiting for the bad news.

When we made it I imagined a stadium full of people bouncing around and dancing their asses off to it. Now maybe it’s one person in their living room with a bottle of Crown Royal on a fucking Thursday night

Dave Grohl

“But this thing that was happening with Nandi served one purpose, which was to bring people joy and happiness at a time when there’s a great shortage of joy and happiness. And at some point I thought, okay, well, isn’t that what music is supposed to do? So what are we waiting for? We wrote this music for people to hear – they should hear it if they want to.”

Grohl laughs. “And sure, when we made it I imagined a stadium full of people bouncing around and dancing their asses off to it. Now maybe it’s one person in their living room with a bottle of Crown Royal on a fucking Thursday night. So what? It’s time!”

Rich is the co-author of the best-selling Nöthin' But a Good Time: The Uncensored History of the '80s Hard Rock Explosion. He is also a recording and performing musician, and a former editor of Guitar World magazine and executive editor of Guitar Aficionado magazine. He has authored several additional books, among them Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, the companion to the documentary of the same name.