“I think Metallica thought that I knew who they were. I didn’t. They thought I was in awe of them – not true… it wasn’t enjoyable”: Whiskey in the Jar was the hardest song Thin Lizzy’s Eric Bell ever tackled, and he didn't enjoy playing it with Metallica

In a wide-ranging conversation with GW, Bell also acknowledges that he could never have returned to Phil Lynott’s band after an infamous onstage meltdown in 1973 – but at least he apologized to his beloved Strat for his behavior that night...

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When it comes to Thin Lizzy, there’s guitar heroics to spare – Scott Gorham and Brian Robertson as heard on Jailbreak (1976), Gary Moore on Black Rose: A Rock Legend (1979), or Snowy White on Chinatown (1980).

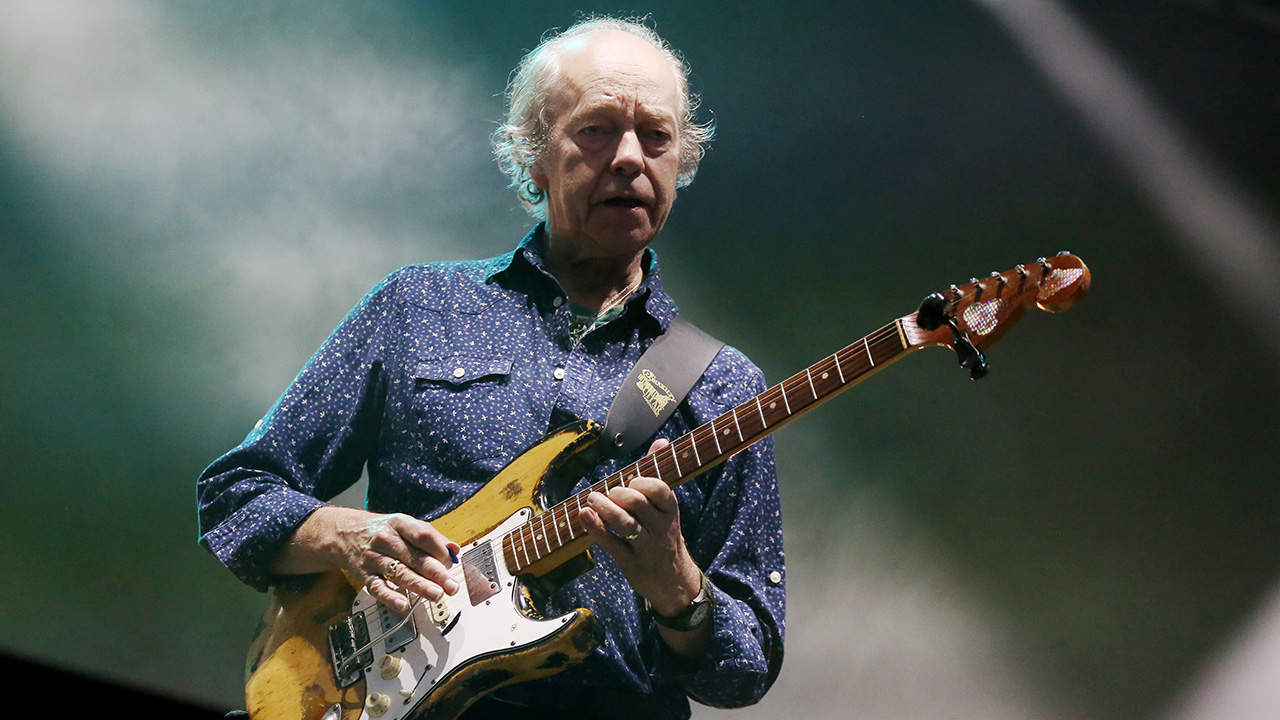

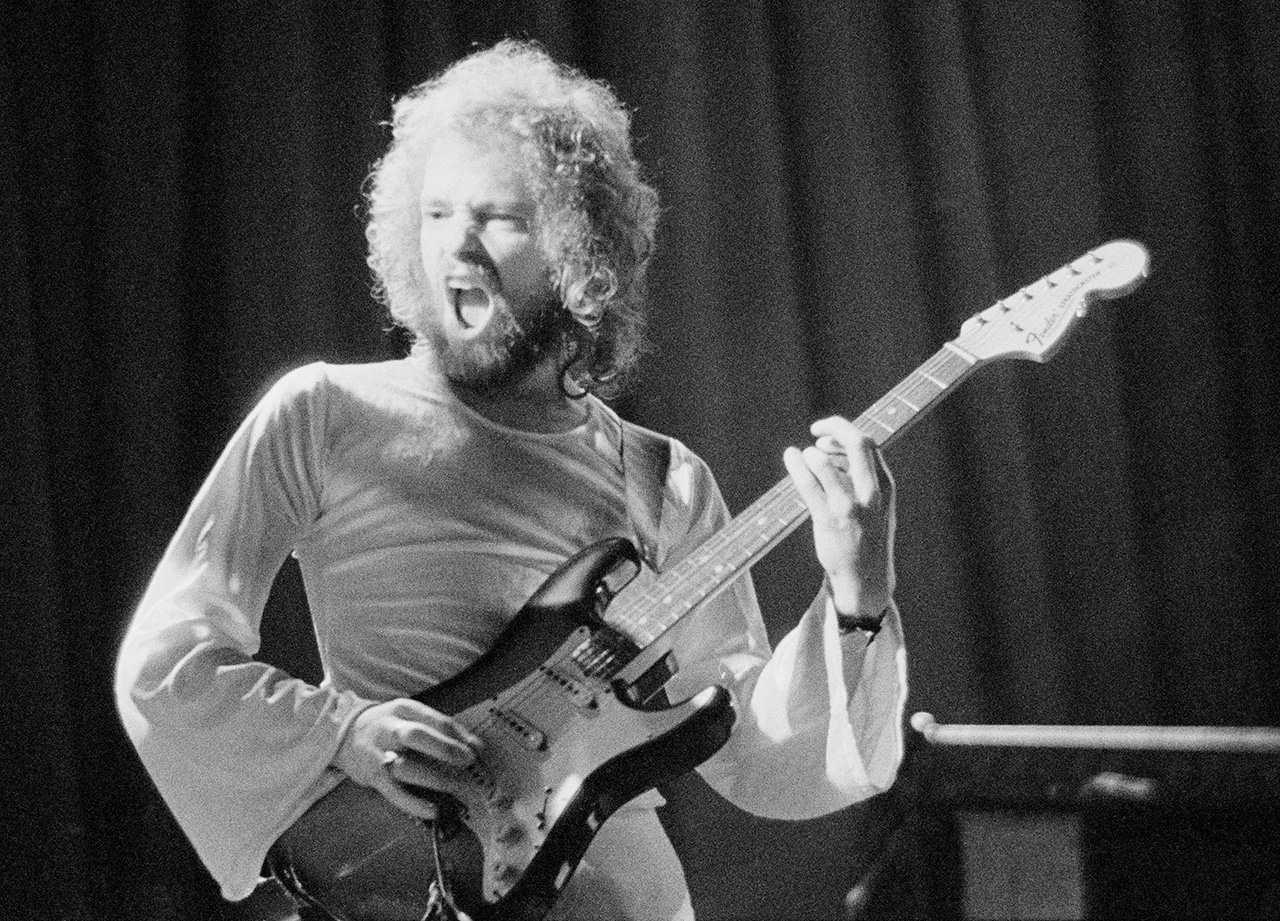

But when the Irish band were a folksy blues three-piece, it was Eric Bell who defined Thin Lizzy on their 1971 self-titled debut, Shades of a Blue Orphanage (1972), and Vagabonds of the Western World (1973).

He proved to be a consummate songsmith with licks for days. He also provided unforgettable tone, demonstrated on iconic tracks like The Rocker and Whiskey in the Jar – the latter covered by Metallica on Garage Inc. (1998).

But Bell was hampered by drugs and alcohol. During a New Year’s Eve show in Dublin in 1973, he stopped the show, threw his Strat in the air, tipped over his amps and then collapsed. He quit the band the next day, ushering in Thin Lizzy’s hard rock-based era.

He’d clean up enough to later play alongside Hendrix alumni Noel Redding before embarking on a solo career, and took the stage with old bandmate Phil Lynott one last time in 1983 (documented on Life) – but didn’t stay in touch.

Asked if he regrets how things ended, Bell says: “I did at first, but the passing of time has changed my mind. If I’d stayed, I’d be dead, like fucking hundreds of other musicians. It got to a point where I was smoking dope and drinking while recording and playing live. I had to stop.”

He continues: “I was up at night, thinking, ‘Eric, the gig is done. No one more’ – but it got out of hand. I had huge bottles of whiskey, Guinness, dope and cocaine everywhere. I had to walk away. I have no regrets.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

What inspired you to pick up the guitar?

“Seeing a cheap acoustic guitar in a local shop window. I was just a boy – I passed this window, and there it was. It looked sharp and was hanging there. I liked the look of it – it seemed like the sort of thing I could have fun with.”

Was that cheap acoustic your first guitar?

“No. I got my first guitar at around 12 as a Christmas present. It was plastic but very well made. It was half the size of an ordinary guitar and had six nylon strings of different colors.

“It may have been plastic, but it was more than a toy – it was my guitar. I remember picking it up and playing it for the first time… I’d forgotten all about it until right now. I wish I still had it.”

What was your local music scene like growing up in Belfast?

“Belfast was always behind England. England always had this and that, and we’d look across the water, saying, ‘When are we gonna get some of that?’ There wasn’t much happening in Belfast, but many people were into music.

“The blues made its way over, along with Van Morrison’s stuff from when he was with Them. Van was an Irish guy and one of the few with good records, so he was very influential as far as music and style went.”

You eventually joined Them in late 1966. How did that happen?

“Van returned to Belfast and the lineup began to shuffle. One day I was in a music shop and Van walked in; everybody stopped talking. It was total silence. Van looked at me, saying, ‘Can you come round tonight and play guitar?’ I was nearly speechless. Here was this legend speaking to me and wanting me to play guitar. So I went over there that night, got my guitar out, and we jammed.”

Do you remember the guitar you brought?

“Before I got my Strat, I had a Gibson ES-330 as my main guitar. I loved that guitar; it was beautiful. But, I always wanted a Strat. While I was with Them we played a gig one night in Ireland, and the supporting act had a Strat. After having more than a few drinks, I traded their guitarist for it.

“I loved my Gibson – but the Strat was the type of instrument you couldn’t really bluff on. I played differently with the Gibson. I loved the sustain I got with the Strat and how I could get a certain type of distortion and breakup.

“I also just liked the look of it. I remember seeing Hank Marvin of the Shadows playing a Strat; and Hank Marvin was, to me, the first guitar hero in Great Britain. He’d jump up there with that pink Strat. So I had to have a Strat of my own.”

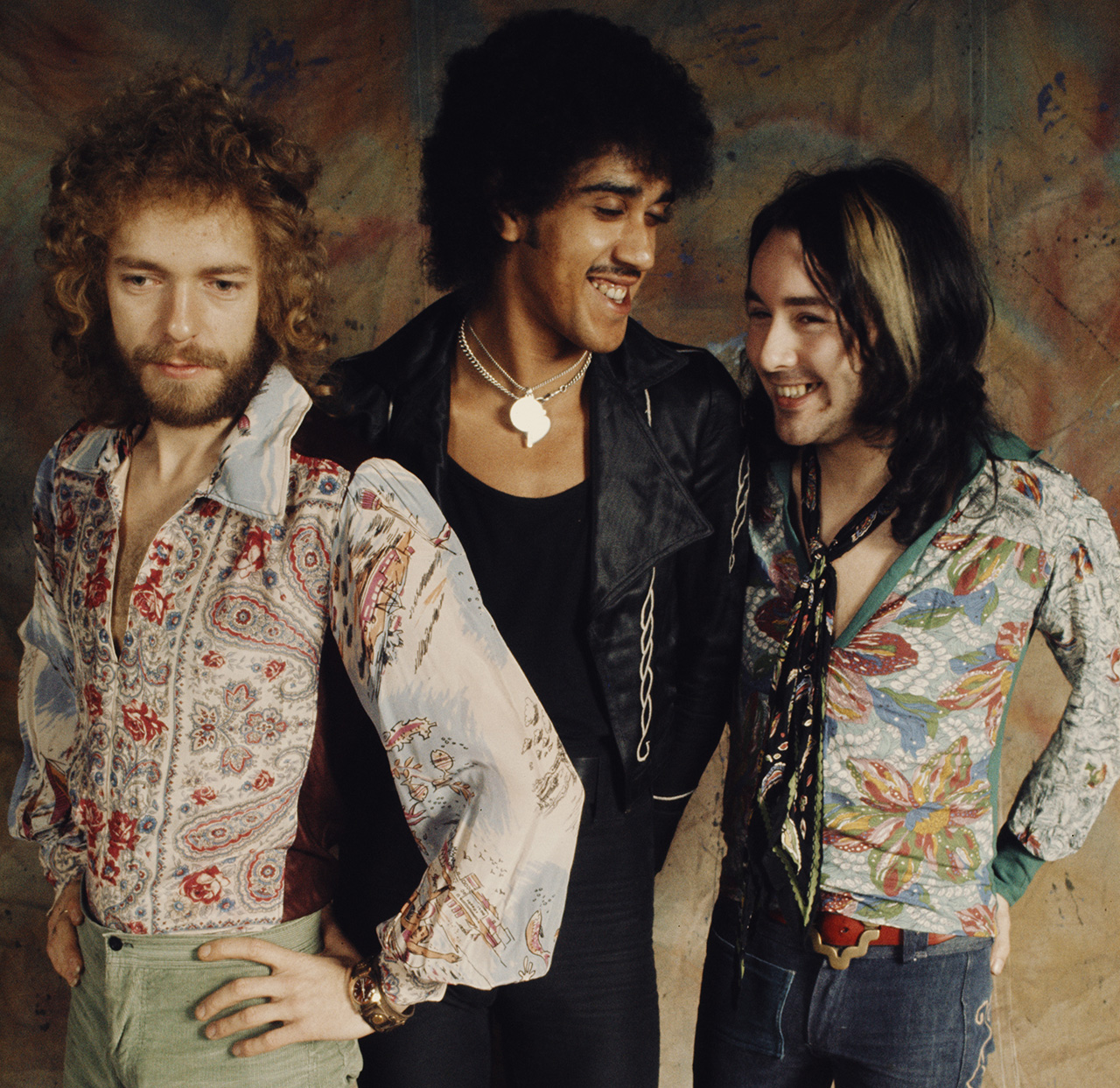

How did you meet Phil Lynott and form Thin Lizzy?

“I was at a club amid my first LSD trip. There was this band playing which had Phil as the singer, though he wasn’t playing bass. I was sitting there watching and the LSD began to kick in – but I could tell Phil was special. He had these impressive vocal chops and great charisma. I thought to myself, ‘Man, if only I could find a guy like that.’

“So when they took a break, Phil went to the dressing room and I followed him. He said, ‘Can I help you?’ I said, ‘I’m looking to form a three-piece band.’ At this point, the acid kicked in again, and I was laughing at everything I saw around the room.

“Phil looked at me like I’d just escaped an asylum and asked, ‘Are you okay?’ I said, ‘It’s my first trip on acid,’ and we kept talking. He told me about a drummer called Brian Downey, and he said to go to the Zodiac Club and find him there.

“As I was leaving, Phil said, ‘I want to play bass, and I want to write my own songs.’ I said, ‘Yeah? Okay – quit your band.’ From there we met for a rehearsal; it was very shaky, but I knew there was something there, and we stuck with it.”

What was it like working with Phil on the first Thin Lizzy record?

“We took a lot of risks. I’d only known Phil for about six weeks then; I remember sitting in the pub and he said, ‘Fancy getting a house together to work on music?’ Many bands were doing that, and we figured it was easier than going into a rehearsal space. We got this space in Dublin, and many of the earliest Thin Lizzy songs were written there.”

After Thin Lizzy, the band moved from Ireland to London for Shades of a Blue Orphanage. Why?

“We’d begun to cause some waves around Ireland. We went from having no one at gigs to having a huge line out the door. I took it for granted, but we kept getting bigger. Our manager said to us, ‘There’s nothing more here for you – you’ve got to move to London.’

“So we went, and started playing six nights a week. But no one knew who we were. We might have been huge in Ireland, but in London we were nobodies. We started from the bottom all over again, and that’s when we went in to do the second record.

“The thing was that we didn’t have enough songs, and since we were working so hard, we didn’t have time to arrange things. The second record was literally made up on the spot.”

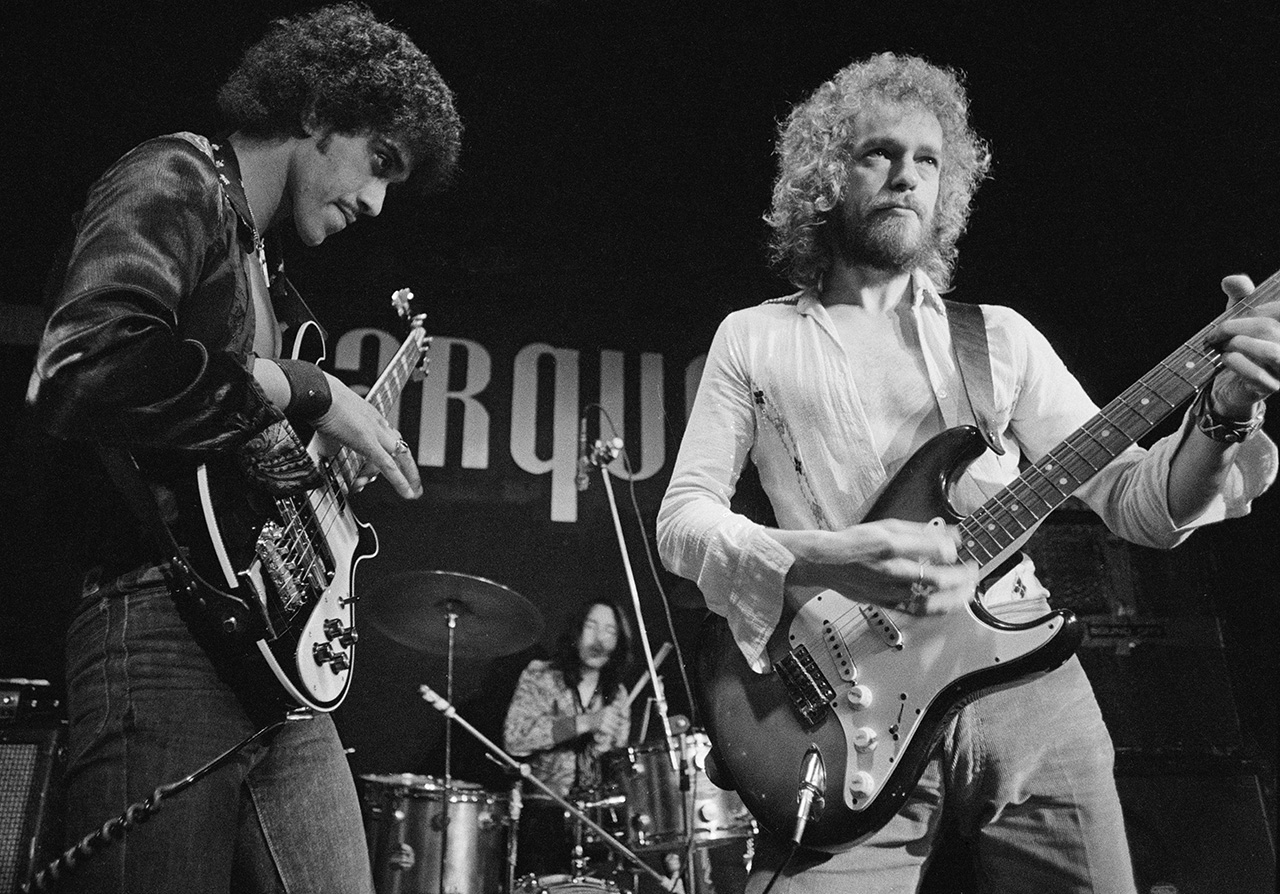

Vagabonds of the Western World seemed more thought-out. Tell me about recording Whiskey in the Jar.

“That was the hardest piece of music I’ve ever worked on in my life. We’d been messing with it in rehearsal. But I thought, ‘This isn’t blues. It’s not funk. It’s not jazz. It’s an Irish folk song – and I don’t know how to approach it.’”

How did you end up working up the iconic guitar solo?

“It was unreal. I’d get up each morning, go to the guitar – and couldn’t think of anything. It went on for weeks, then Phil started calling: ‘We need this done!’

“One night we played in Wales, and while driving home I was sitting in the back seat. I went into this dreamlike state and started thinking about Irish pipes. I said, ‘Right, forget about the guitar. Let’s run with this.’

“I heard Irish pipes in my brain, and the solo started forming in my mind. I’d never thought that way before. Once I’d gotten into the song and the solo was underway, I hit it hard as it was happening. It was just one of those special moments where every note worked. It was very unusual.”

What gear did you use?

“I had a very strange setup. When I got to London, I had a Vox AC30, but it went missing. I was trying a lot of different amps, and I ended up trying a Vox with two PA speakers. I tried a Hiwatt and a Marshall but I didn’t like them.

“Our manager got me this transistor amp, and when I plugged it in Phil said, ‘There’s no valves!’ It had a treble booster that I paired with this echo chamber. I plugged the Strat in, cranked the volume to the edge, and off I went.”

Vagabonds of the Western World showed promise, but it all came crashing down during the band’s New Year’s Eve show in ’73.

“A lot had happened by that point. I was only in my 20s, and we’d ended up in London, which I hated. I couldn’t handle it being so different from Ireland. I went down a slippery slope of drinking and drugs, and we were hardly making any real money.

I could barely raise my arms, let alone play the guitar. I couldn't get it together, and even though we were used to playing stoned, this was different

“I’d be held up in my attic apartment all alone when we weren’t gigging. It was fucking horrible. I wasn’t looking after myself – I’d be drinking, taking Valium, and other drugs. By the time we got to the New Year’s Eve show – which was part of an Irish tour – I was like a zombie. I had no idea what I was doing.

“So we get into Belfast, our hometown, and I’m on a lot of drugs before the show at Queen’s University. It was sold out, and I drank half a bottle of whiskey to calm down.

“Then It was time to go on – and I couldn’t do it. Drinking all the whiskey had me feeling like a giant was smothering me; I could barely raise my arms, let alone play the guitar. I couldn't get it together, and even though we were used to playing stoned, this was different.

“I said, ‘Eric, you should not be doing this gig. You’re not capable.’ So Phil and Brian launched into the set, and by the third song, I was gone. This voice in my head said, ‘Get out of here. Leave this situation, or you’ll be dead.’

“Then the voice said, ‘Throw the guitar in the air, kick the speaker over, and fucking get out.’ Before I knew what I was doing, I saw my guitar in the air in slow motion, and I went and pushed my amp over.

“People thought it was an act, but I collapsed under the stage. And the crew ran over, yelling, ‘Get back out there!’ But I said, ‘No, I’ve had it. I’ve left the band.’”

Did they try to talk you into staying?

“The following day our manager phoned me up, saying, ‘What the fuck is going on?’ I said, ‘Listen, I’ve left the band.’ He said, ‘You can’t. You’re halfway through this tour.’

“I said, ‘I’m just not there. I’m not capable.’ At one point they might have taken me to a clinic to dry out; but he said, ‘Okay. That’s your last word?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ Then he said, ‘Right. I’m getting Gary Moore,’ and he hung up. That was it.”

Did Phil call you after Brian Robertson left Thin Lizzy in the late ‘70s?

“No. Phil didn’t want me to rejoin because he didn’t trust that I wouldn’t do what I’d done again, which I got. He also wanted guys with long, flowing locks who could jump around. I didn’t fit that image. I was a fucking musician, not a gymnast.

“I mostly stood there and wasn’t concerned about being a good-looking bloke. For Phil, if they could play blues scales at full volume while looking good, that was all he wanted.”

Did you agree with the direction that Phil took Thin Lizzy?

“It was a different band. With me there was a lot of acoustic stuff and folk-inspired songs that were bluesy and psychedelic. But Phil leaned on harder stuff with Brian and Scott Gorham in the band.

“Don’t get me wrong – those albums were excellent, just not how it might have been. Thin Lizzy became a superb band, just a completely different one than I was in.”

You did return for their 1983 show, along with all Thin Lizzy's other guitarists, save for Snowy White.

“All I remember are the walls of Marshall amps. I’d never seen anything like it. I walked in and there was this massive wall of amps, and Phil said, ‘I want to do The Rocker.’

“So, we did the soundcheck, and at one point I stopped playing – and nobody noticed. There were so many guitars, and it was just deafening. I couldn’t escape it; I thought, ‘Man, I am not into this.’ I felt like crying; it was a real take-no-prisoners deal.”

In 1999, Metallica called you to perform Whiskey in the Jar in Dublin. Did that catch you off guard?

“I didn’t know anything about Metallica. Not a thing. I’m not into that type of music. So when someone told me they’d recorded Whiskey in the Jar I was like, ‘Oh, who are they?’

“And then they asked me to do the gig, which was chaos. I don’t know why they called me. I think the impression they had was that I knew who they were. I didn’t. They thought I was in awe of them – not true.

“One of the roadies drove me to their hotel, and I stood in the hall waiting. And one by one, they came down, shook my hand, and they expected me to be impressed. But I didn’t know who they were, I’d never heard their music, and I wasn’t bothered. That took them by surprise.”

There was no chemistry… I’m hearing Whiskey in the Jar in F, which was very odd. My brain wasn’t into it. I just played it my way, and we went our separate ways

What was the experience of playing with them like?

“It wasn’t enjoyable. There was no chemistry. They tuned a whole step down, which is typical for them. I, however, didn’t. So now I’m hearing Whiskey in the Jar in F, which was very odd. From that point forward, my brain wasn’t into it. I just played it my way, and we went our separate ways.”

Do you still have the Strat you tossed into the air during your final show with Thin Lizzy in 1973?

“I do! I have other guitars, but my main one is the same Strat I used with Thin Lizzy. I’ve had it for about 50 years, and I play it daily. I call it Old Faithful because it never lets me down.

“I had a drunken conversation with it one night where I said, ‘I’m sorry I threw you up in the air in Belfast. Can you please forgive me?’ I believe it has.”

- Keep up to date with Bell and his Eric Bell Trio via Facebook.

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.