“Interviewers were telling me that I started the whole glam rock, hair metal scene. I said, ‘What? Don’t blame me for that!’” Drugs, guitars, triumph and tragedy – the inside story of Hanoi Rocks

40 years ago – after moving to London to invent the movement that would inspire a million L.A. bands – Finnish upstarts Hanoi Rocks self-destructed. This is their story

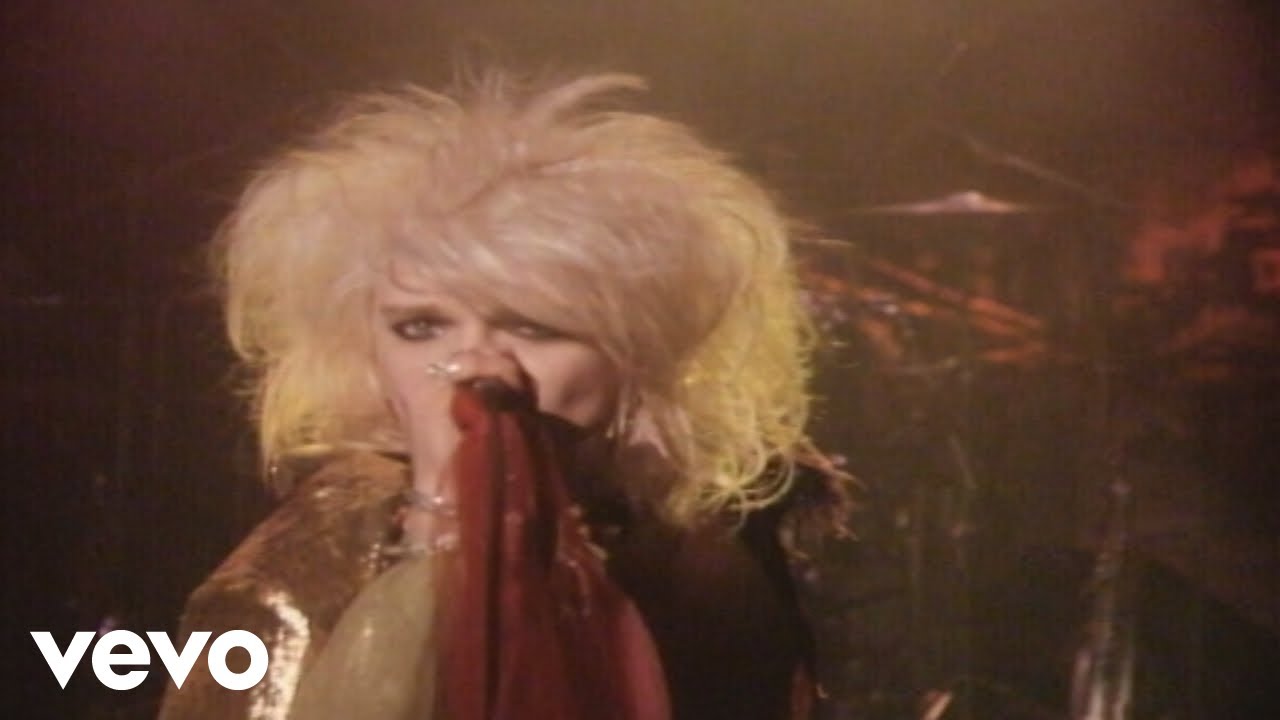

![Hanoi Rocks' Andy McCoy [left] and Michael Monroe. Monroe wears a bright gold jacket and has blonde, '80s rock-sized hair. McCoy is cradling a black Gibson Firebird and weats a wide-brimmed hat.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/98AkCWXe6Q87uhPDBaybQd.jpg)

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Are Hanoi Rocks the most underrated rock band of all time? The Finnish rockers had everything – anthemic songs, an unrivaled live show and a killer guitarist in Andy McCoy. And then there was singer Michael Monroe, the most charismatic, photogenic frontperson, male or female, since Elvis Presley.

Taking their cue from the New York Dolls and Johnny Thunders’ Heartbreakers, cut through with the snotty attitude of classic U.K. punk, they distilled their own uniquely potent brand of sleaze-fueled, take-no-prisoners rock ’n’ roll.

Hanoi Rocks’ live show reminded you of why you got into music – the adrenaline rush of loud electric guitars through a wall of Marshalls set to stun, and a frontman who had the audience in the palm of his hands.

A Hanoi Rocks show was an event. No matter the size of the venue or the crowd, the band delivered every night as if their existence depended on it. Monroe was in perpetual motion, McCoy pulled off every move in the guitar-hero playbook, and rhythm guitarist Nasty Suicide and bassist Sami Yaffa managed to hold their own. Drummer Razzle was so busy, he looked like a blur.

Unfortunately, tragedy knocked the band sideways when Razzle was killed in a crash in 1984 while a passenger in Mötley Crüe vocalist Vince Neil’s car. Although the band continued for a few months, relationships frayed and decayed until they finally fractured. The band split up the following year.

Monroe and McCoy each had firm ideas on what a band should be.

“Nothing I was doing prior to the band was really where I wanted to be musically,” Monroe says. “I didn’t really have a musical partner who shared my vision until I met Andy. Once we met, we knew what sort of band we wanted to have, even before we formed Hanoi. It was a couple of years before we got together in the same band; I guess we shared a dream.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“He told me about Aerosmith, but I wasn’t that familiar with them. I got Get Your Wings after that. I thought Steven Tyler and Joe Perry were a little like Robert Plant and Jimmy Page, where the focus was mainly on those two guys.

“Someone like the New York Dolls, who I really liked, was different, though – everybody in the band was a strong individual, in contribution and appearance, and I always thought that was what a band should be like. I thought it would be really cool to have a band where everyone was equally interesting.”

![Hanoi Rocks in 1984 [L-R]: Nasty Suicide, Sami Yaffa, Andy McCoy, Mike Monroe, Razzle](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/fZLfuSA6ymimVL483Yq6jn.jpg)

Criminally under-appreciated nowadays, Hanoi Rocks were hugely influential on the U.S. metal scene in the early ’80s – musically and visually.

“There wasn’t really much happening when we first got to America in 1983,” Monroe says. “It was kind of a post-new wave era. There wasn’t any real scene going on. When I went back, after I started my solo career a few years later, interviewers would be telling me that I started the whole glam rock, hair metal scene.

“I remember saying, ‘What? Don’t blame me for that!’ Anyway, we were always a hat band, not a hair band. [Laughs] I think it was funny when all of a sudden people were looking like me. I was always anti-fashion, thinking everyone should have their own style, not all look like a template.”

Hanoi Rocks defied categorization, mixing influences ranging from ’50s rock ’n’ roll through classic rock, punk and metal. “Anything from Little Richard to the Stones and the Ramones,” Monroe says. “We felt like we could play anything – we even had a calypso song.”

Anything from Little Richard to the Stones and the Ramones. We felt like we could play anything – we even had a calypso song

Prior to forming Hanoi, McCoy had been in Briard, releasing the first-ever Finnish punk single, I Really Hate Ya, in 1977. Having built a rep prior to teaming up with Monroe, McCoy always had a sense that Hanoi was his band, causing an undercurrent of tension that’d rise to the surface sporadically and ultimately bring the band to its knees.

Hanoi’s mission was plain from day one; they wanted to break out of Finland and into the U.K. and U.S. markets, writing and singing in English. They also adopted English-sounding names – Matti Fagerholm became Michael Monroe, Antti Hulkko morphed into Andy McCoy, Yaffa changed his surname from Takamaki and Jan Stenfors became Nasty Suicide.

“We wanted to get out of Finland as quickly as possible,” Monroe says. “For rock ’n’ roll, English is the only language, really.”

The first step to breaking out of Finland was a move to Stockholm, Sweden. As Monroe recalls, there was more than musical ambition that drove the move.

It was getting dangerous to be in Finland looking the way we did. Stockholm was just a ferry ride away, and over there it was an entirely different scene

“In Finland, in the late ’70s and early ’80s, there was a weird resurgence of ’50s style. We called them James Deans. They were racist motherfuckers, and they’d beat up anybody with long hair. It was getting dangerous to be in Finland looking the way we did. Stockholm was just a ferry ride away, and over there it was an entirely different scene.

“I never wanted to become a famous band in Finland anyway, as I didn’t want to get stuck there. We knew we could get gigs in Sweden, and we saw it as a stepping stone to moving to London. No band ever thought of leaving Finland before us, so I guess we paved the way.”

But once in Stockholm, the band found themselves struggling to make ends meet. “We were basically homeless,” Monroe says. “Andy had a rich girlfriend, so he lived with her, but the rest of us were living rough, maybe getting a few nights with some girl or whatever.”

“We were literally living on the street and sleeping in the rehearsal room for a while,” Yaffa adds. “It was quite a rough time. We ended up living with refugees from Afghanistan.”

Back to Monroe: “We had very little money and we were always starving. It felt like us against the world. We felt like we were all part of a gang, though I guess Andy wasn’t really a part of that. The music was all that mattered to us, giving 2,000 percent every show. It was like an all-out attack when we went on stage.”

The move to Sweden paid off, with the band being given the opportunity to record their first album – Bangkok Shocks, Saigon Shakes, Hanoi Rocks – in 1981. An instant classic, featuring perennial favorites Tragedy, Lost in the City and Don’t Never Leave Me, it was the band’s ticket to England.

Although initially only available as an import, the U.K. music press was enthusiastic and Hanoi toured relentlessly up and down the U.K., moving to London in 1982.

A second album, Oriental Beat, followed within months and again delivered the goods, featuring Hanoi classics such as Motorvatin’ and the title track. The band was riding high in the U.K. by this time, so much so that their Finnish record company released a cash-in compilation of outtakes and demos, Self-Destruction Blues, to give the band their second album of the year.

Hanoi were unhappy at the record company’s move – but not because of any concerns about running out of new material. McCoy was a prolific songwriter, but he was always reluctant to share credits with the rest of the band, regardless of their contribution.

I’d always been frustrated by the writing process. Andy would write everything and would insist he wanted it a certain way

Michael Monroe

Monroe: “I’d always been frustrated by the writing process. Andy would write everything and would insist he wanted it a certain way. I wasn’t always convinced he was right, and I’d have a lot of ideas. I think they improved the songs, but I’d have to fight for them, and I never got any credit for what I added. It was my own choice, and I wasn’t worrying about publishing and shit back then.”

That changed when the band released their fourth album, Back to Mystery City, in 1983. Widely considered by fans to be their best work, it marked a major step up in terms of songwriting and production.

As Monroe says: “By the time of this album, I’d started to assert that I wanted to have a lot more input. Andy would come up with great ideas, but they’d be unfocused in terms of the finished song, and I’d work hard at structuring and arranging things so that they made sense, making the most of what Andy had come up with. I learned a lot about arranging from [Dead Boys vocalist] Stiv Bators, who was a great friend of mine.”

Mystery City was the first album to feature new drummer Razzle, aka Nicholas Dingley. “Me and Andy were very much on the creative side," says Monroe, ”and Sami and Nasty were very much the soldiers, and you need guys like that in the band; they’re all part of the team.

“If everybody is fighting to get songs on the record and trying to get their own material into the show, you end up like the Eagles. [Laughs] You have to split, because everybody wants to do their own thing. Too many creative people. When Razzle joined the band, he made the chemistry complete – he was perfect.”

McCoy’s take on the band’s contributions was markedly different. In a 1981 interview with U.K. rock publication Sounds, he said that, apart from Monroe, the rest of the band were just background musicians and relatively unimportant.

It was a view he maintained years later when interviewed for the definitive band biography, Hanoi Rocks: All Those Wasted Years, which was recently republished by Cleopatra Records.

The success of the album attracted attention in the U.S., leading to CBS signing the band and setting them up with producer Bob Ezrin. As a fan of his work with Alice Cooper, it was the perfect combination for Monroe. Although there were high expectations from their first major label, Monroe wasn’t fazed.

“I didn’t feel the pressure,” he says. “I was just excited, particularly with Bob on board. Everyone was so fucked up then anyway that we wouldn’t have even been aware of pressure. Andy might have been the exception, as he was feeling under duress to come up with material. Smack was a big thing for the band in ’84, though, and that was messing with everything.”

“I was really excited,” Yaffa adds. “I got [to see] Alice Cooper when I was a kid; [bassist] Dennis Dunaway was one of my biggest heroes.”

During the prep for what was to become the band’s fifth album, Two Steps from the Move, things weren’t going well in the Hanoi camp, however.

“Bob was exactly what we needed,” Monroe says. “The morale of the band was terrible. We’d rehearse, do half a song and then someone would say, ‘Let’s go to the pub.’ I wasn’t really a drinker then, so it was a bit frustrating. Bob saw us live and then told our management he wanted to meet me first.

“That annoyed Andy. He said, ‘Why you? I’m the writer?’ [Laughs] Bob had a whole lot of great tips for the live show and my performance – things I took on board to refine the way I performed on stage.

“He said, ‘We have one problem, but I’m sure I can handle it.’ I said, ‘What, Andy?’ He laughed and said yeah, but [Andy] reminded him of [guitarist] Glen Buxton from the Alice Cooper band, and he knew how to deal with him.”

McCoy was undoubtedly the factor that frequently served to unsettle the band’s dynamics. A vocal advocate of his own abilities as a songwriter and a guitarist, the problem was that he was usually right.

Often to be seen wielding a range of cool vintage semi-acoustic Gibsons, McCoy could peel off face-melting solos at will. Unafraid to mix genres, McCoy could happily take an unexpected detour from classic blues-based rifferry into flamenco-flavored stylings before slipping seamlessly into classic Delta blues – all within the same lead break.

Ezrin remembers that McCoy could run though up to nine takes of a song, with each solo taking a different approach – and each one a potential keeper.

The album’s basic tracks were recorded in New York City in February 1984, although pre-production work started in Toronto the month before, where the rest of the album would be completed.

Ezrin knocked the band into shape, insisting on an intensive rehearsal schedule, which managed to pull them back, temporarily, from the brink of self-destruction. McCoy was persuaded to share writing duties with one of his heroes, Ian Hunter.

Hunter had been lined up to produce Mystery City but had been unable to fit it into his schedule. His contributions added an increased maturity to the writing, enabling the band to record their most mainstream, commercially appealing album.

“I think it showed how much we evolved as a band,” Monroe says. “We went up to the next level without losing anything. Ezrin was really important in helping refine everything. He was very hands-on.”

When CBS heard Two Steps, they insisted the band needed a hit single and therefore needed to record another song.

“The label wanted a single – they didn’t like the record,” Monroe says. “We were on tour, and we’d been playing the Creedence Clearwater Revival Albert Hall album [1980’s The Concert, recorded in 1970] in the tour van, so we decided to pick one of the songs from that. We went for Up Around the Bend. It was that or Bad Moon Rising.

“We did it in one day in London, and Bob came over for it; he sings one of the harmony vocals. It did well for us and scored us our biggest hit single.”

“I always felt Two Steps sounded too American – too polished and not enough sleaze,” McCoy offers. “Mystery City was my favorite Hanoi album.”

We did some shows where Nasty and I were so sick on stage we could barely stand. It got to the stage where people started calling us the suicide twins

Andy McCoy

The release was delayed until the fall of 1984. In the meantime, the band toured the world, generating hysteria in Japan along the way. Although they appeared to be finally breaking through internationally, relations within the band were becoming tense.

Substance abuse was the root of most of the problems, though McCoy’s dictatorial attitude didn’t help. McCoy remembers that he and Suicide had developed a “serious smack habit” to the point that it was compromising their ability to deliver on stage.

“We did some shows where Nasty and I were so sick on stage we could barely stand,” he says. “It got to the stage where people started calling us the suicide twins.” During the summer, Hanoi met Mötley Crüe, who were playing in London and struck up what was to become a fateful friendship.

On the back of Two Steps selling 40,000 copies in the U.S. in its first week, November 1984 saw the band kicking off their first American tour. Their previous albums had been available only as expensive imports in the States, but they’d already built a strong following, and the relentless exposure they’d been getting on MTV since the release of Up Around the Bend had helped ratchet up their profile.

Duff McKagan and Izzy Stradlin were regulars at their shows. McKagan was quoted as saying Hanoi were one of the premier influences on Guns N’ Roses, who would go on to re-release the band’s records on their own UZI Suicide label.

Halfway through the tour, Monroe injured his foot jumping off a drum riser and a number of shows were pulled. The band relocated to L.A. while Monroe recuperated. For drummer Razzle, this was everything he’d wanted from a life in a rock band – touring the States and partying in L.A.

When Vince Neil heard that the band were in town, he invited them to a party at his house that had already been in progress for a couple of days. Monroe didn’t go, but McCoy, Yaffa and Razzle did. At one point, Neil realized they were running low on booze and said he was driving to the store to stock up.

Asking if anyone wanted to go with him, Razzle volunteered. He’d been admiring Neil’s red 1972 Ford Pantera. On the way back from picking up the beer, Neil lost control, skidding into a car coming the opposite way and wrecking the Pantera. They’d been traveling at 65 mph in a 25-mph zone. Razzle was taken to the hospital, where he died at age 24.

Neil was later found guilty of vehicular manslaughter and driving under the influence of alcohol. He paid $2.6 million in damages but spent only three weeks in jail. Razzle had a tattoo on his arm: “Too fast to live, too young to die.” Unfortunately, that turned out to be untrue.

For the rest of the band, things seemed to change with the passing of their drummer. Razzle was the glue that kept the band together. Whenever arguments broke out along factional lines, Razzle, impervious to the divide, would remind them just how lucky they were to live the life they’d dreamed of and had struggled for so many years to achieve.

Razzle’s death was the straw that broke the camel’s back

Sami Raffa

A few years older than the rest of the band, he was able to bring a different perspective to the camp. “It was a tragedy the band couldn’t recover from,” adds Monroe. “It was the beginning of the end.”

McCoy, who formally identified Razzle’s body at the hospital, has never made any secret of his own feelings about Neil’s actions, frequently voicing his anger at the events and Neil’s subsequent punishment.

The fact that Crüe released a couple of box sets titled Music to Crash Your Car To in 2003 probably didn’t help. John Corabi, who sang with Crüe in the late ’90s, has recalled that McCoy once tried to attack him, thinking he was Vince Neil, shortly after the release of the box sets.

On returning to London, discussions took place about whether to carry on or not. Within weeks, Yaffa left, having already been feeling that things were no longer the same anyway, in part due to friction with McCoy.

“Razzle’s death was the straw that broke the camel’s back,” Yaffa says. “We were already really fragile as a band because of all the drug use and [differing] personalities. We were still a very good band and if Razzle hadn’t died, who knows what would have happened, but we were also very young and we didn’t really have the ammunition to try to deal with that kind of trauma.”

With two key members down, Monroe felt it was impossible that suitable replacements could be found. Touring commitments were fulfilled with former Clash drummer Terry Chimes taking Razzle’s spot.

“We would never have found two more guys with the same spirit who were two of the best friends we ever had,” Monroe said.

“We did some auditions, but it wasn’t right. Our managers pushed us to keep going, as we were getting a certain amount per month, and when we wanted to split they asked us to hang on so everyone could get paid. I had no money anyway and it wouldn’t have maintained the integrity of the band to keep going.”

When Hanoi finally split in 1985, Monroe relocated to New York to embark upon a solo career. McCoy and Suicide formed the Cherry Bombz, a female-fronted venture that was – musically – not unlike Hanoi Rocks.

Although Hanoi never made the leap to household-name status, their influence was immense. Foo Fighters’ Chris Shiflett was active on the L.A. scene when Hanoi arrived and recalls that there was almost an overnight shift to the decadent flamboyant style the band embodied. According to Shiflett, leather and studs went out, and scarves and makeup took over. Plenty of acts were taking notes.

Monroe’s subsequent success as a solo artist has eclipsed that of his former band members. McCoy has formed a number of bands since the demise of Hanoi, though without notable success. Yaffa had spells in Jetboy and the New York Dolls before becoming a member of Monroe’s band; he’s also recorded two solo albums.

Nasty retired from the music business to work – without any sense of irony, given his years of copious substance abuse – as a pharmacist. He has been tempted out of retirement in recent times to play some sporadic shows celebrating the legacy of the band and also released a solo album, Stenfors, in 2022.

There was a short-lived reformation of Hanoi Rocks in 2001, when Monroe and McCoy convened a new lineup and recorded a couple of albums. Though well received, it was hard to refute the sense that something was missing.

Monroe looks back with pride and fondness when recalling the rollercoaster ride that was Hanoi Rocks.

We were certainly never big enough to be considered for something like the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, but I think we were a very cool band whose influence went far beyond our expectations

“We never had the sales that matched the influence we turned out to have,” he says. “I don’t worry about it; I guess we never made it to the next level. I suppose we were one of those well-kept secrets. We were certainly never big enough to be considered for something like the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, but I think we were a very cool band whose influence went far beyond our expectations.

“We were always true to ourselves – that was the most important thing to us. Rock ’n’ roll has become ever more rare now; it seems like a different world. The integrity of the band and my solo career have always been important – never sell out, always mean what you do and do it for real. It was always about making fun music; that’s what bands in the past were all about.

“Songs were made for the right reasons. Everybody had their own thing; nobody was trying to be part of a movement or something. Nobody was looking for a shortcut like TV talent shows. The music was always more important to Hanoi Rocks than the partying, whatever it looked like from the outside.”

- This article first appeared in Guitar World. Subscribe and save.

Mark is a freelance writer with particular expertise in the fields of ‘70s glam, punk, rockabilly and classic ‘50s rock and roll. He sings and plays guitar in his own musical project, Star Studded Sham, which has been described as sounding like the hits of T. Rex and Slade as played by Johnny Thunders. He had several indie hits with his band, Private Sector and has worked with a host of UK punk luminaries. Mark also presents themed radio shows for Generating Steam Heat. He has just completed his first novel, The Bulletproof Truth, and is currently working on the sequel.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.