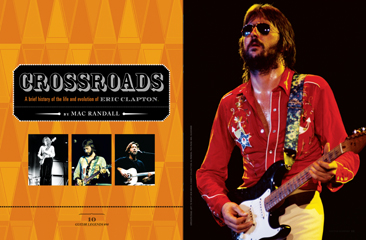

Eric Clapton: Crossroads

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A brief history of the life and evolution of Eric Clapton presented by Guitar World magazine.

“I try to find the places I’ve been before,” Eric Clapton told an interviewer in the early Nineties. “To go back and find a phrase which has a meaning, that belongs to some part of my experience, is very valuable to me because it will put me in touch with something that may involve lots of thought processes that I had forgotten, which are still quite valid.”

In this statement is the key to understanding most of Clapton’s output in the past 15 years, a period in which he’s enjoyed his greatest commercial success and highest level of mainstream fame. Having long ago proven everything he needed to as a musician—guitarists were calling him “God” when he was barely into his twenties—the Clapton of the late 20th and early 21st centuries has chosen to delve deep into his own history, reconnecting with the music, and sometimes the musicians, who inspired him in younger years. This is all a roundabout way of saying that to fully grasp the significance of what he’s doing now, you have to be aware of his past. And few pasts are more illustrious than Eric Clapton’s.

Eric Patrick Clapton was born in the southeastern English town of Ripley on March 30, 1945. He was the illegitimate son of a 16-year-old girl and a married Canadian army officer who had hightailed it back across the Atlantic before the boy was born. Clapton’s mother soon vanished from his life in a similar fashion, moving to Germany and leaving him in the care of her parents, Rose and Jack Clapp (Eric’s surname was borrowed from Rose’s first husband, Reginald Clapton). For a time, Clapton believed that his grandparents were actually his parents. When Rose and Jack revealed the truth, he became depressed, withdrawn and a poor performer in school, failing the exams that would have enabled him to progress to university.

In previous eras, a young man in Clapton’s situation would have been drafted into the armed forces. But the U.K.’s then-recent abolition of compulsory national service meant that he was free instead to enter the realm where so many sensitive youths with few career prospects ended up in the early Sixties: art college, the fabled crucible of British rock. Though Clapton had an aptitude for painting and graphic design, his interest in any kind of academics withered as music rapidly became the main focus of his life. He’d begun playing guitar in his early teens, inspired by the American blues of Big Bill Broonzy. By the age of 17, he was devoted to the instrument, and his intensive practicing interfered with his course work to such an extent that the Kingston College of Art expelled him.

Before long, Clapton had become a central figure in London’s blues subculture, playing with a number of local bands and drawing praise for his powerful guitar style. In 1963, he joined the highly regarded Yardbirds, and on the one full-length album he cut with the group, 1964’s Five Live Yardbirds, his solos bore a raw authenticity that left other Brit wannabe bluesmen in the dust. It was around this time that Clapton acquired the nickname “Slowhand,” an ironic comment on both his speedy fingerwork and the slow handclaps he’d get from audiences while replacing broken strings onstage (a frequent occurrence).

Clapton’s tenure in the Yardbirds came to a messy end after the band had a major pop hit with “For Your Love” in 1965. The blues purist in him couldn’t abide such a transparent grab for chart success. He jumped ship, to be replaced by Jeff Beck and, eventually, Jimmy Page. Clapton’s departure from the Yardbirds set the tone for the rest of his career, establishing him as restless and unwilling to commit to creative dictates that weren’t his own. His next phase, as a member of John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, would last barely a year, but during that time he helped create what is generally regarded as the greatest British blues album ever recorded and arguably the greatest white blues album of all time: 1966’s Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton. Having switched from a Fender Telecaster and Vox AC30 to a Gibson Les Paul and Marshall 1962, Clapton unleashed a scorching overdriven roar that’s considered a pinnacle of electric guitar tone to this day. He also sang for the first time on record, covering his hero Robert Johnson’s “Ramblin’ on My Mind.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

An apt title, to be sure, for by the time Blues Breakers was released, Clapton had already moved on to form Cream with bassist Jack Bruce and drummer Ginger Baker. The ultimate example of the power trio, Cream played blues rock with a psychedelic edge, a style they worked to perfection on hits like “Sunshine of Your Love,” “White Room” and a supercharged version of another Robert Johnson song, “Crossroads.” Over four albums and three U.S. tours, the band won America over with its lengthy jams, powered by Clapton’s magisterial guitar. But in May 1968, the group’s ascent came to a halt when Clapton read a scathing review of a Cream live performance in the then-new, hip magazine Rolling Stone. The article “said how boring and repetitious our performance had been,” Clapton later recalled. “And it was true! The ring of truth had just knocked me backward; I was in a restaurant and fainted. And after I woke up, I immediately decided that that was the end of the band.”

Within months, Cream was history and Clapton had formed a new band, Blind Faith, with Baker, Traffic singer/multi-instrumentalist Steve Winwood and bassist Rick Grech. Sadly, this early prototype of the supergroup quickly fell apart under the weight of outside expectations, leaving behind just one roughedged, but appealing, studio album. A subsequent tour with American roots-rockers Delaney and Bonnie spawned Clapton’s first solo record, simply titled Eric Clapton, in 1970. Although the album was successful and featured a Top 40 cover of J.J. Cale’s “After Midnight,” Clapton remained uncomfortable as a frontman. He went underground, bringing together several Delaney and Bonnie cohorts in a new configuration that would eventually be called Derek and the Dominos. Joined in the studio by another brilliant guitarist, Duane Allman, they recorded the 1970 double-disc Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs. The album sold poorly at first, in part because many didn’t realize it was Clapton’s project, but both it and its anguished title song are now acclaimed as rock masterpieces.

The heartache so palpable in Layla’s grooves was real: Clapton had fallen in love with Pattie Harrison, the wife of his best friend, ex-Beatle George Harrison. Convinced his feelings would never be requited, he took refuge in drugs. By the end of 1971, Clapton was a serious heroin addict and had dropped out of music entirely. In 1974, after a traumatic withdrawal, he re-emerged as a solo artist once and for all with 461 Ocean Boulevard, which helped introduce reggae to a wider audience via its hit version of Bob Marley’s “I Shot the Sheriff.” But Clapton’s addiction hadn’t really disappeared; it had just switched its allegiance from heroin to alcohol and would continue to dog him for years to come.

At first, the music didn’t seem to be affected. The albums he released in the late Seventies include one of his all-time best, Slowhand (1977), which boasted such evergreens as “Cocaine” and “Wonderful Tonight.” Clapton got the girl, too, marrying Pattie in 1979 with faithful friend Harrison in attendance. However, his luck ran out in the early Eighties, and life-threatening bouts with bleeding ulcers and pleurisy finally led him into rehab in 1982.

The new, clean Clapton became an even bigger star in the Eighties, but for the first time he seemed to lack confidence in his direction. The eclectic Behind the Sun (1985), produced with Phil Collins, unsettled the heads at Warner Brothers, who insisted that five tracks be scrapped and replaced with more commercial material. Uncharacteristically, Clapton caved to the label’s demands, and the finished album, along with its successor, 1986’s August (another collaboration with Collins), made longtime fans wonder where Slowhand’s edge had gone. By the end of the decade, however, Clapton had regained his self-assurance. Journeyman (1989) was his strongest studio effort in over 10 years, and his live energy was undiminished, as he demonstrated most notably with a record-breaking 1990 residency at London’s Royal Albert Hall, documented later on 24 Nights (1991).

By this time, his relationship with Pattie had dissolved, and Clapton had taken up with Italian model Lory del Santo. In August 1986, their son, Conor, was born. Tragically, in March 1991, the four-year-old fell to his death from a window of a New York apartment building. Stricken with grief, Clapton bared his feelings in the song “Tears in Heaven.” The tribute received its debut at Clapton’s 1992 appearance on MTV’s acoustic performance series Unplugged and now stands as his biggest solo hit. The Unplugged album that followed has sold more than any other Clapton disc and won six Grammy Awards, including Album of the Year.

The years since this bittersweet triumph have seen Clapton venture back and forth between the poles of tradition and experimentation. On pop-oriented albums like Pilgrim (1998) and Reptile (2001), he’s dabbled with sampling and electronic beats. Retail Therapy, his 1997 technoambient collaboration with keyboardist/ producer Simon Climie released under the name TDF, is a further testament to his interest in stretching boundaries. But these developments have been overshadowed by Clapton’s deepening engagement with his first love, the blues. In 1994, he recorded an all-blues album, From the Cradle, on which he paid tribute to many of his musical idols. Six years later, he joined forces with one of those idols, B.B. King, for a delightful album of duets, Riding with the King. And in 2004, he devoted another full disc to the classic work of Robert Johnson with the heartfelt Me and Mr. Johnson.

But the Eric Clapton of the 21st century hasn’t just been interested in returning to his blues roots; he’s also been interested in revisiting several phases of his own past, and he’s done so in ways that are surprising and unprecedented. In 2002, he reunited with John Mayall for a live performance in celebration of Mayall’s 70th birthday; it was the first time the two had played together in over 35 years. Then, in 2005, Clapton got back together with Cream bandmates Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker for a series of magical shows at the Royal Albert Hall. Highlights of the group’s four-night London stand were released on a CD and DVD, and later that same year, the trio electrified audiences at a few more shows at New York’s Madison Square Garden.

Clapton’s trip down memory lane didn’t end there. In 2006, he teamed with J.J. Cale, author of such old Clapton chestnuts as “After Midnight” and “Cocaine,” to record a laid-back set called The Road to Escondido. More recently, he toured the world with a band that included Austin guitarist Doyle Bramhall II and young slide guitar master Derek Trucks, of the Allman Brothers Band. The latter association reconnects Clapton with the spirit of the late great Duane Allman, with whom Clapton made some of his most enduring music in the early Seventies.

Why all this looking back? A remark Clapton made to the BBC in 2005 on the occasion of his 60th birthday may offer a clue: “I find I’m always looking for something to put right,” he said. “Because there’s always something that I did wrong before that I have to make amends for.” Now 62 and secure in his position as one of the greatest guitarists to ever walk the earth, Eric Clapton wants nothing more or less than to set his own personal record straight. And as he continues to do that, he makes the millions of people who love his music very happy indeed.