“I was very appreciative to be there. But when he transitioned to Let’s Dance, I wasn’t called back. I eventually squared with it, but it was painful”: George Murray on his bittersweet ride with David Bowie

The D.A.M. Trio bassist performed on a run of classic Bowie albums including Station to Station, Low and “Heroes”. He recalls nearly missing the call-up to catch a bus, meeting his replacement Carmine Rojas in an elevator (and what he nearly said), and the studio sessions that made music history

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

David Bowie’s music was decidedly mercurial, with hits that embraced glam, pop and classic rock. Within those pockets of chart-topping ecstasy lay moments of hyper-fluid experimentation, which could surprise even the staunchest Bowie supporter.

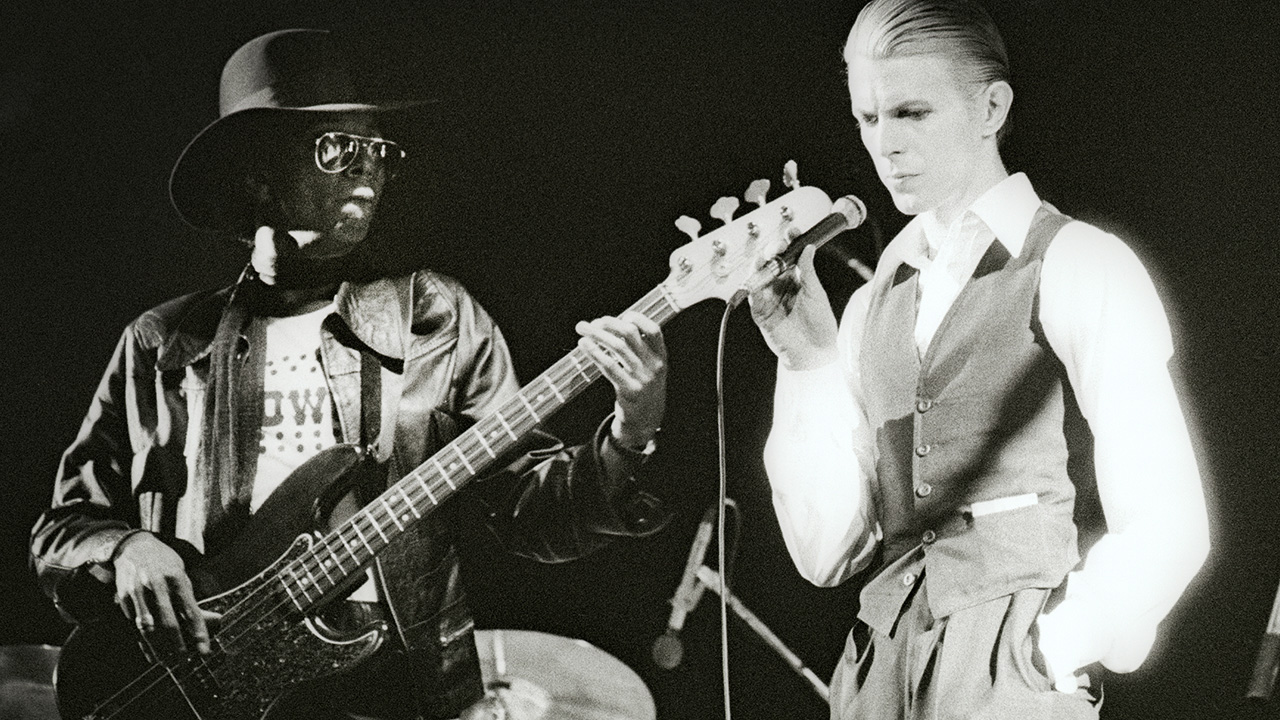

Such shifting music required the shifting of musicians, too; and one of those was George Murray, who held down the low end from 1976 to 1980. Alongside Carlos Alomar (guitars) and Dennis David (drums), Murray formed The D.A.M. Trio, who helped Bowie deliver some of his most challenging albums: Station to Station (1976), Low and “Heroes” (1977), Lodger (1979) and Scary Monsters (And Super Creeps) (1980).

Murray wasn’t called back after Scary Monsters. He wasn’t fired or decisively replaced – the phone just stopped ringing. It was a tough pill to take, and he struggled with it for a time, leading to his leaving the music business altogether by 1986.

These days, though, he’s put it behind him, and alongside his former bandmates, he’s prepping for a return to action. “Carlos and I may be doing something later on this year, showcasing the music that we recorded with David as the D.A.M. Trio,” Murray tells Bass Player. “It’s not finalized, but it’s almost finalized.

“And I’m scheduled to appear at the Bowie fan convention in Liverpool in July. I’m looking forward to the convention – though not looking forward to the flight!”

What inspired you to pick up the bass?

“In sixth and seventh grades, it was the sounds I heard on the radio. My parents would have the radio on in the car, and jazz on the radio on Saturday afternoons around the house. My uncle wanted to be an opera singer… he wasn’t successful in that, but he was a hell of an electrician!

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I was pulled in to music just as The Beatles broke, and all that music from the UK – The Dave Clark Five, The Yardbirds and John Mayall caught my ear.”

Can you remember your first bass?

“I read something from Bass Player with [Bowie’s next bassist] Carmine Rojas in January… Carmine and I have very similar backgrounds and similar histories. He wanted to be a drummer, and I wanted to be a drummer.

“My parents didn’t have enough money to afford a set of drums, even though I was able to take drum lessons. I had a rental set for a little while, which was an antique. But no matter how much snow I shoveled or lawns I cut, I wasn’t making a dent in the price tag. A bass guitar was a little bit more affordable.

“The first one I had was a Hagstrom short-scale bass. The first thing I remember being able to grasp was Purple Haze by Jimi Hendrix. I was always looking for performers who liked the kind of music I did, and when Jimi released Are You Experienced, that’s one of the main licks that I remember nailing, because it was simple. Another reason I picked up the bass was because I figured I could grasp those concepts, those notes, easier.”

Once you became more established, what did your first proper bass rig look like?

“I played the hell out of that Hagstrom for years and years and years. In college, I think, the first good bass that I got was a Fender Precision Bass. And it was a beautiful bass. It had a satin finish to it, not a gloss finish, and it had a maple neck.”

And how about amps?

“I went through several amps earlier in my career. I’ve been partial to Ampeg, though I used Acoustic and Fenders. When I showed up for the first rehearsal with David Bowie, he said, ‘What do you want to play through?’ I said, ‘An Ampeg SVT.’ So that was what I had: a straight Fender Precision and an SVT, and I recorded through that.”

How did you get the gig?

“I got a call – the same as Carmine Rojas did. But I almost missed the call that day. Around New York City I’d met Dennis Davis and Carlos Alomar, and I knew they had the Young Americans gig with David.

I looked at the experience pretty much as a live audition until I got the offer to go on tour

“We were knocking around New York City doing independent things, recording here, playing there. One day in September 1975 – a warm day – I left the house to catch a bus. I had forgotten something; I don't know what it was. As I came back I heard my father say, ‘Wait a minute, wait a minute, here he is!’

“I walked in and he handed me the phone. It was Dennis letting me know that David was looking for a bass player. He wanted to know if I’d come out to Los Angeles to work on Station to Station. I said, ‘Sure!’”

Is that when you initially met David Bowie?

“I met him at a rehearsal studio on Coalinga Boulevard, when I went to start rehearsal. I looked at it as a live audition to work with David Bowie and my friends, Carlos and Dennis. I looked at the experience pretty much as a live audition until I got the offer to go on tour.”

Working on Station to Station must have been an interesting dynamic. You guys were a rocking New York City band, while Bowie seemed to have distinctly UK sensibilities.

“It came about in a number of ways at the first rehearsal – which, I might add, is the only album we rehearsed before we went into the studio that I remember.

“David, when he came into the studio, said, ‘Hi, my name is David.’ I said, ‘I’m George,’ and we went from there. The first song he laid out for us was Golden Years, and he explained the premise behind why he wrote it.

“Many think their golden years are something they enjoy much later in life, but the idea was that your golden years are being formed in the moment you’re in. And I grabbed onto that piece of information.

“To this day, it’s still one of my favorite, if not my favorite, songs I recorded with David. That underlying rhythm just grabs you and pulls you along as it grooves.

Station to Station was one of the few times he gave me something to play. Most of the time he’d just say, ‘Here’s the changes,’ and we’d go from there

“If you listen to it closely, with Dennis’ hi-hat parts, and the way the guitars interchange with each other, you can see a little bit of what was known as the Philly groove going on underneath it.

“Then we moved on to Station to Station – I looked at it as a song with three separate parts, or three separate movements, that David had presented. We worked on all three of those parts separately but played them together. I remember it as being one full take.

“I don’t know if David had cut anything or sliced anything together as far as rhythm tracks; but just listening to it, I don’t think so. And on the first movement, David gave me that bassline to play, and we latched on to it naturally.

“That was one of the few times he gave me something to play. Most of the time he’d just say, ‘Here’s the changes,’ and we’d go from there. We kind of felt those parts out for ourselves.”

From there, you made the trio of records – Low, “Heroes” and Lodger – on which David collaborated with Brian Eno. Those records erred toward electronica, contrasting with what the band brought.

“I tell folks that it was a unique experience with all these experimental things that David was doing at that time. I kind of think he did it because he had to give these albums to RCA.

“This is just my perspective, but I think he took the opportunity to really give them the ideas and the concepts that he was interested in at that time. And his interest, I think, helped form that bond with Brian Eno. I don’t know what their history was before that.

“The electronics, mixing and experimental stuff usually came after I was gone. The rhythm tracks went down as rhythm tracks, and in that, concepts were presented, like, ‘We kind of want it to sound like this; we want it to feel like this,’ or ‘Dennis, will you play that backward?’ – which he did on a couple of things.

The surprise comes when you hear the finished product coming back at you. It took some adjustment

“But Carlos, Dennis, and I played the rhythm. We nailed it down, kept it going, and we were able to experiment within the rhythmic structure. David was happy with that; it gave him a foundation to lay on whatever else he wanted to lay on top of it, along with Brian.”

It must have been exciting for you as a young bass player to be working with Bowie and Eno during such an explorative period.

“It was, because it was different – different but exciting. All of it was exciting. It was more than I’d hoped for or even imagined up to that point.

“But the surprise comes when you put something down, and you remember it one way, and then you hear the finished product coming back at you. It took some adjustment, listening to how David used our contributions.

“The sounds were very different; that’s probably the best way that I can explain it. And you know, the albums – especially the second album, Low, that we did at the studio in France – was almost unrecognizable to us when we got it back.

“When I would play something for a friend or an associate, I would look at their reaction when they heard it. They would have a puzzled look on their faces because it wasn’t what they were used to. It was unique, introspective and far-reaching. I’m still enamored that I got to do that with him.”

You wrapped up your time with Bowie with Scary Monsters, which was a little less experimental and featured the classic Ashes to Ashes.

“No, that was kind of experimental also. The rhythm tracks were a little... I don’t want to say elusive, but they took a little thought to grab onto. By that time, I was using a different bass for recording – I had a B.C. Rich Eagle. I think they’re discontinued; I still have that bass, though.

“One of the pickups was out of phase and I was experimenting with different sounds on different tracks. Again, I was a little surprised by what the finished product was – not quite as much as Low, but I was surprised. Ashes to Ashes is one of my favorites.”

After Scary Monsters, did you keep in touch with Bowie?

“We didn't have any more contact. The last contact I remember having was when we did the Saturday Night Live performance. I think we did The Man Who Sold the World and Boys Keep Swinging. That was the last time I saw David. He did other things on small, medium and large scales.”

I found myself in the elevator with Carmine… I was tempted just to say, ‘Are you playing my parts right?’

You had such a remarkable run with him; that must have been disappointing.

“When I got the call in 1975 to work on Station to Station, I knew I was replacing somebody. I didn’t ask why; I didn't want to know. I would hear things and I just filed them away. But I kind of thought to myself, ‘Yeah, one day, I won’t be here anymore; but I don’t know when that’s going to be.’

“So for the time I was there, I was there, and I was committed. And with all the good – hardly any bad – just all the good that went along with it, I was very, very appreciative to be there.

“But when it was over, it was over. I just didn’t get called back. When he transitioned to Let’s Dance, I don’t want to say I was left behind, but I wasn’t called back. I wasn’t fired – I just wasn’t called back.

“I eventually squared with it, but it was painful. Going back to Carmine, who stepped in to replace me… David was in town, Carlos was in town, and Carmine was playing on that tour; and I had to go to their hotel, the Westwood Marquis, on the west side of Los Angeles.

“My wife at that time worked at the hotel, and I had to give her something or whatever. So I had gone up to see Carlos, and as we were coming back down to the lobby, I found myself in the elevator with Carmine and Carlos.

“I was tempted just to say, ‘Carmine, are you playing my parts right?’ But the little voice in the back of my head said, ‘George, don’t say that. It’s unprofessional and uncalled for. Just leave it be.’ And I did. I just let it be. But I had to struggle with it for years.”

What did your life look like after Bowie?

“I moved to Los Angeles in 1979. I packed up my stuff, drove over the George Washington Bridge, and I never looked back at New York. I was one of those California dreamers; I thought I would enjoy a similar degree of success in Los Angeles as I had in New York.

“People tried to convince me to stay, but I kind of made up my mind made up on it. I wasn’t able to duplicate that same degree of success in Los Angeles. I did continue in the music business for a while, but nothing panned out.

I worked in studio instrument rentals… until I had to wrestle a Hammond B3 up the stairs, and I said, ‘This ain’t happening’

“Things started to diminish; I couldn’t find a lot of work. And the work I could find I really didn’t want to do – although there were some very enjoyable moments. I had a number of jobs over that time.

“I worked in studio instrument rentals for a little while, so I was on the other side of the equipment; until I had to wrestle a Hammond B3 up the stairs with somebody, and I said, ‘This ain’t happening.’

“Then I was a delivery driver for a florist in Beverly Hills, which helped me pay the rent and work on my other projects. But I couldn’t survive on what I was making, so I started working for one of the local school districts here in 1987, the Alhambra Unified School District. I stayed there for 35 years.

“I didn’t do hardly any music. My wife at the time was the musician in the family. My participation in the music industry subsided from 1986. I hadn’t really performed until October of 2023, when I started stepping out again.”

Now you’re back out there celebrating it, how do you view your contributions to Bowie’s catalog?

“Looking back now, I realize I just so fortunate to have had that experience and been able to work with Dennis and Carlos and all the people I met along the way.

“I look at it as David taking the opportunity to say, ‘Okay, if I gotta give RCA the albums, I’m going to give them what I want to give them and not worry about anything else,’ which I think he might have done.

“I don’t know whether that was truly his motivation, but I was fortunate. I’m happy to have been part of that and am very happy now, looking back on everything.”

- Murray appears alongside Alomar at the David Bowie World Fan Convention in Liverpool, UK in July.

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.