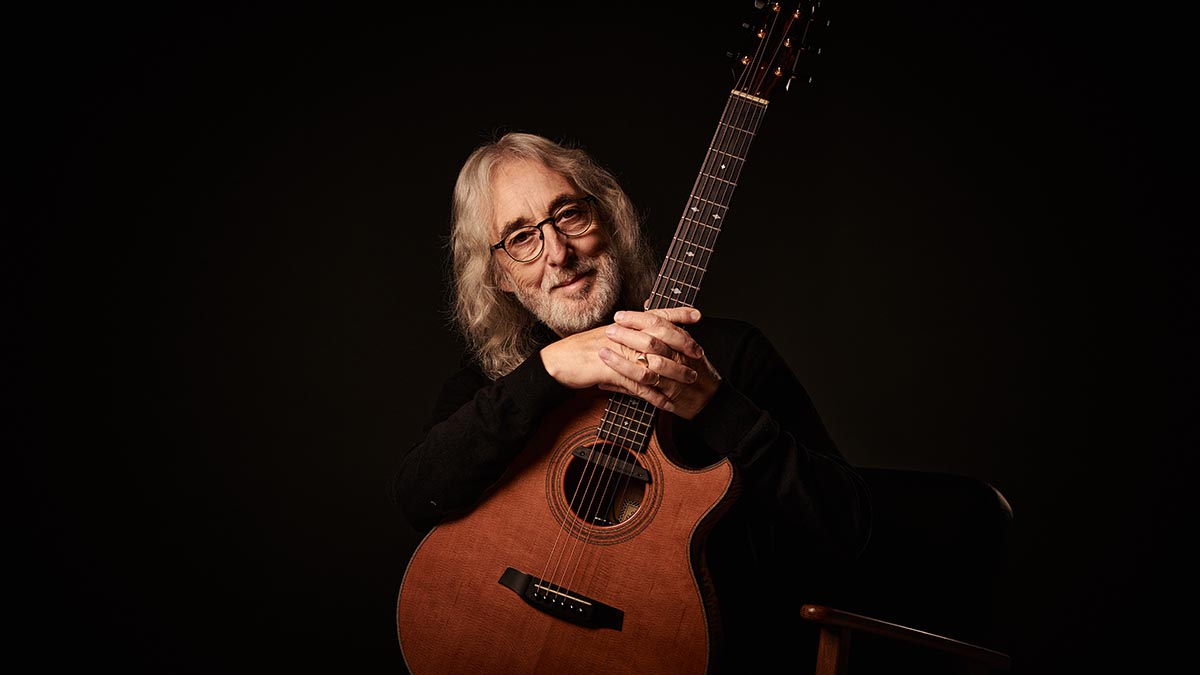

Gordon Giltrap: “All the best stuff comes when you’re not thinking about it. It just flows: you start off with a one-bar idea and then build up on that”

What is good music? What is good guitar playing? It can take a lifetime to arrive at meaningful answers, as acoustic master Gordon Giltrap reflects when we join him to discuss his powerful new album, Scattered Chapters

One of Britain’s most gifted fingerstyle guitarists, Gordon Giltrap took inspiration from the heavyweights of the ’60s folk scene, Bert Jansch and John Renbourn, before embarking on his own recording career in 1968.

Self-taught, Giltrap’s lyrical acoustic style has a joyous, universal quality that arguably even his heroes lacked and a distinctiveness that owed in part to Giltrap being a self-professed “ignoramus” when it came to standard guitar technique. After becoming a regular on the BBC’s flagship serious music show The Old Grey Whistle Test, crossover hits such as Heartsong from his 1977 album, The Perilous Journey, followed, making Giltrap a household name – to his bemusement.

“I had no idea it would be a hit record, no idea,” Gordon recalls. “But then it started selling. And next thing you know you’re on Top Of The Pops and they ring you up and they say, ‘Oh, you sold 15,000 singles today,’ and you think, ‘I don’t know these people – how come they bought my record?’

“But the next day it was 25,000 copies sold in a day. It’s very hard to get your head around the fact that suddenly you’re selling a lot of records. Suddenly, you’re known nationally, not just among the people that like guitar playing or have seen you on The Old Grey Whistle Test. Suddenly, you’re a pop star, whether you like it or not.”

But anthems such as Heartsong are only one facet of an ever-evolving body of work that today spans 28 albums and more than 50 years of music-making. Giltrap’s road through music – and life at large – has been long and, at times, marked with tragedy.

The sum of all this experience has now been distilled into his latest album, Scattered Chapters, co-written with keyboardist and arranger Paul Ward. As a tapestry of instrumental pieces, the thread that binds it together is a vivid strand of emotion, which is anchored in profound personal experiences and a rare humility.

For Giltrap, good music-making is not about handing a loudhailer to your ego but becoming open to the flow of creativity.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

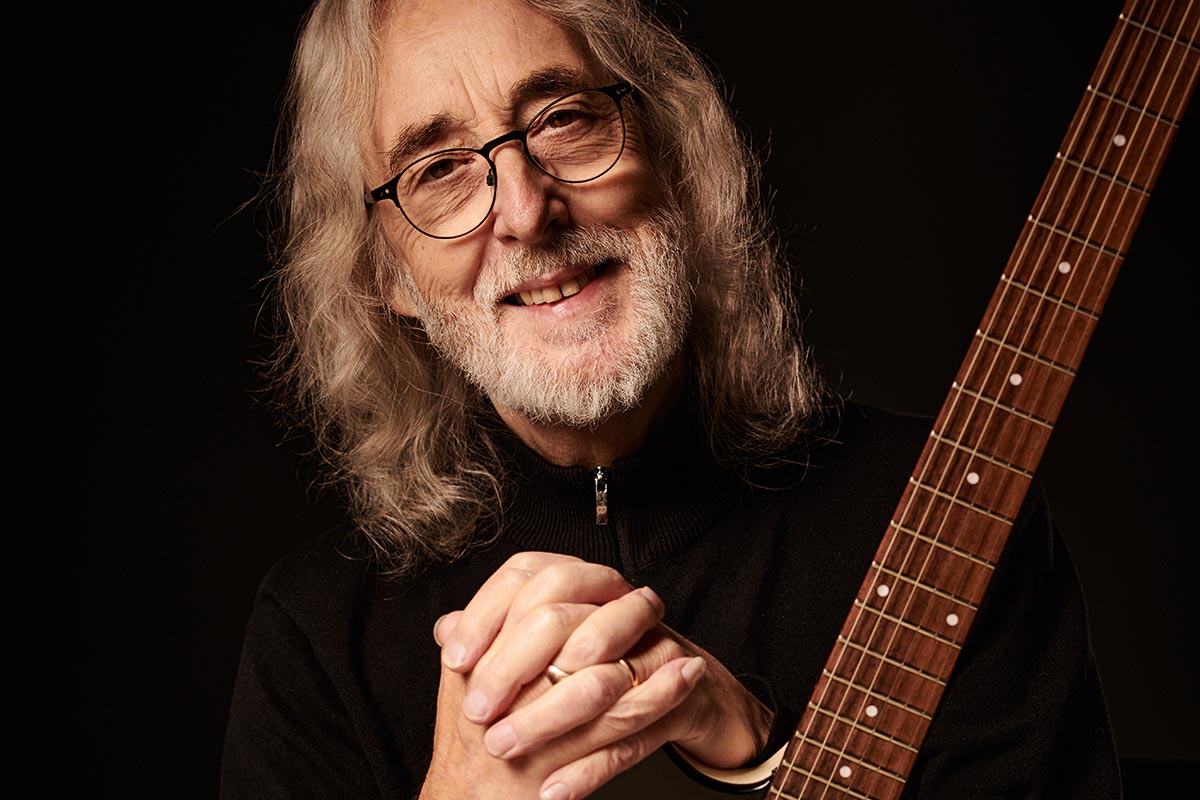

“All the best stuff comes when you’re not thinking about it,” he reflects. “And it just flows. Basically, you start off with a one-bar idea and then build up on that. And, eventually, it’s like a jigsaw puzzle: you keep putting the pieces in and then eventually you end up with a [finished] piece and then you step back from it. And you say to yourself, ‘How did I do that?’”

That simple but deceptively deep question is one Giltrap has been pondering for decades. And he’s happy to share his hard-won insights on what the art of guitar playing is really about in a wide-ranging and often philosophical conversation that begins with his new album and touches on life, death and the “absolute bollocks” that drives us to buy more guitars than we really need…

You share the limelight on the album with Paul Ward, playing a minimal role on some tracks and leading on others, yet it all hangs together beautifully.

“Well, I have an incredible relationship with Paul Ward, almost a psychic connection. All his parts were recorded in Sheffield, where he lives, but not once did we meet – everything was done by sending the tracks [via file sharing]. And then he would put on the track what he thought was right for it.

“Nine times out of 10 it was dead right. But, of course, he was using orchestral samples and one of the great masters of [arranging strings for contemporary music] was Del Newman, who I worked with on the Troubadour album. I’ve known Del since 1977, he was a genius.

“I said [to Paul], ‘Listen to what Del did on [1998’s] Troubadour, the way he mixed the strings.’ At the time, Del said he wanted to do the arrangements and produce the album because ‘I didn’t want your guitar to be buried’. So the guitar is always there and the strings are under there to complement it and I just let Paul do his thing.

“But we have this amazing relationship and the main thing that’s taken out of the equation is ego. The man doesn’t have an ego – he says, ‘Gordon, if you aren’t happy with something, tell me. I don’t have an ego, it’s not a problem. We’ve got to serve the music or serve the tune.’ And that’s how it came about.”

Through Braden’s Door is one of the standout pieces on the new album, both as a piece of guitar playing and in terms of emotional impact – what’s the backdrop to it?

“Through Braden’s Door is a very powerful piece of music. My son died in 2018. And that was a very dark, difficult period for all of us in the family. I’d lost a son. My grandson Braden had lost his father, my daughter-in-law [Karen Giltrap-Barnes] lost her husband. Karen rang me up one day…

“I’d given Braden a little three-quarter sized classical guitar and shortly after his dad had died, Braden was in his bedroom. He was just strumming the open strings and singing something – some words that had come to him. He would have been six, seven years old.

I’m a prime example of somebody who’s done everything wrong and somehow it turned out right

“And his mum was walking past the door and she said, ‘I heard Braden singing and I just looked through the crack in the door, at what he was doing.’ And in my mind I visualise that scene: if I’d been there, I would have been witnessing this little boy trying to express how he felt about losing his father. And so that’s how the piece came about.

“Now, when I first wrote it, I gave it to Paul and for some reason, he said, ‘I’m having trouble trying to write an arrangement for this.’ I listened to it again and I said to him, ‘Do you know, Paul, it’s because the piece isn’t finished. I’m going to rewrite it.’ Again – take ego out of the equation: it’s not good enough, it’s not right. So I rewrote it.”

Another captivating piece from the current album is One For Billie. What tuning is that in?

“Thank you. That was originally on the Ravens And Lullabies album [2013] with Oliver Wakeman and I’d recorded it to a click track just in case Oliver needed that, but I wasn’t happy with it because it was too rigid. I always thought, ‘One day I’m going to re-record the way it should be. With lots of space, lots of rubato, lots of emotion,’ because it was written for my wife, Hilary.

“Now, her childhood nickname is Billie and even a lot of her family members still call her Billie. So I thought we’re gonna write a piece for Hilary called One For Billie. That came about from a tuning [C G Eb F Bb D] I’d come across years before that, which I learned from a session player called Terry Johnson who was in the pit band for Blood Brothers. He said, ‘You gotta hear this tuning – it’s a Joni Mitchell tuning,’ Which it is. So I tried it and thought, ‘Oh God, this is fantastic.’ So thank you, Joni Mitchell, for that tuning.”

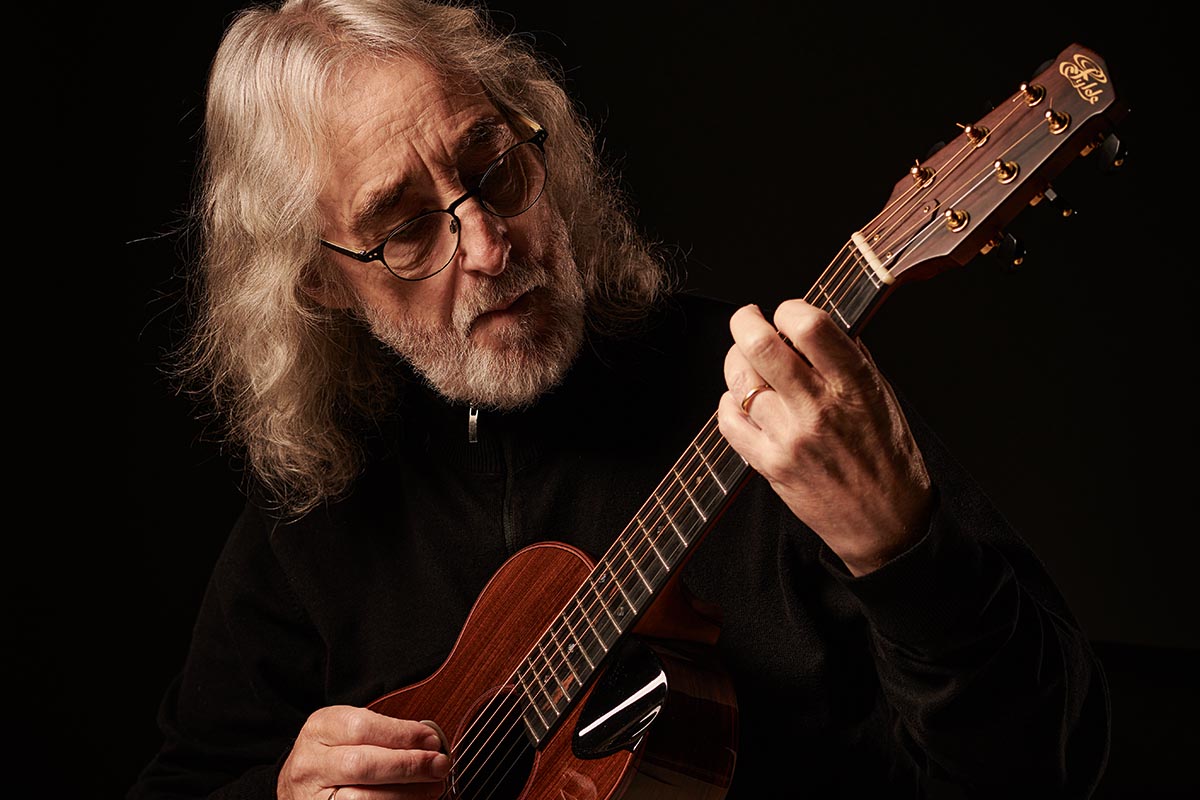

Your playing has become a benchmark for anyone aspiring to play acoustic fingerstyle – yet some aspects are unorthodox, such as your use of a pick and little finger to pluck strings. How did you develop your style?

“I’m a prime example of somebody who’s done everything wrong and somehow it turned out right. Seriously, from the word go. I look back on my life in absolute wonder, thinking, ‘How did this happen? Who is this bloke Gordon Giltrap?’ I was born with an unusual name, which I hated. But it’s a gift – two ‘Gs’, you can remember it.

“How did my parents, who were working-class folk, come up with a name like Gordon? That’s not a working-class name – I should have been maybe a Derek or an Albert or something, but I wasn’t. So I left school at 15, with no education, and I was playing the guitar from the age of 12, but then everybody else was, too, you know?

Most of the guitar players from my generation, who were born in 1947 or 1948 [or 1949] – myself, Mark Knopfler, Richard Thompson… we’re all influenced by Hank Marvin, all of us, because he was the first great guitar hero

“Most of the guitar players from my generation, who were born in 1947 or 1948 [or 1949] – myself, Mark Knopfler, Richard Thompson… we’re all influenced by Hank Marvin, all of us, because he was the first great guitar hero. And we didn’t realise it at the time, but the man was a bloody genius. He created that sound. It was in his fingers, but he also had the vision to use the right amplifier, the delay and the Strat. He owned it, that sound. So I was doing all I could to sound like Hank Marvin.

“And then I got turned on to the acoustic guitar and I was listening to Bert Jansch and John Renbourn. And wanted to be like [Bert] – I even wanted to look like him, which I did, funnily enough. But my hair was too smart to be like Bert.

“Actually, I’ll tell you a funny story. When Bert was ill in hospital I went to visit him. I’d just come from a meeting with the record company and I had a load of early photographs that they wanted to use. I was showing Bert a picture of me when I was about 18.

“And he said, ‘What’s with the hair?’ Because I was a Mod, you see? I wanted to be attractive to girls. But Bert was like Dylan. The way he looked was the way he was: that wasn’t contrived. Bert was Bert, he was totally happy within his skin; he didn’t feel the need to impress anybody. That’s what he was.

“But, anyway, I left school at 15. Tried to sound like my [acoustic] heroes. I had no idea that they used their fingers [of the right hand] to play the guitar. I was such an ignoramus because I was still using the pick, thinking, ‘How can I pluck two notes at once?’ Then the little finger crept in and I thought, ‘Well, okay, I can use that,’ and it stayed like that. And here I am at the age of 74 and it’s still like that.”

It’s all too easy for people to think of quirks in their own playing style as ‘faults’ to be pruned out rather than unique qualities.

“Yes – many years ago, I said to Ray Burley, who is a scholastic musician and a great classical player, ‘Ray, do you think I ought to learn to read the dots?’ He said, ‘Don’t do it – because what you do theoretically shouldn’t work. But it does.’ He said, ‘You’ve broken all the rules, but you do it your way and it works. And if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.’ And I think that’s relevant to a lot of people.

“They think, ‘Well, I’m a blues guitar player. I love Stevie Ray Vaughan – I want to spend my life getting the sound he does. And how did he get that sound? Well, I’ll use 13-gauge first strings and whatever else he did to get that sound.’ But you want to say, ‘No, that’s him. You’re never gonna sound like him. You’ve got to be yourself.’”

Another insecurity that guitarists can fall prey to is that they don’t believe they are ‘proper’ guitarists unless they can play with blistering dexterity, even though good feel, timing and melody usually matter more to listeners.

“Yeah, that’s a lesson of youth versus experience in a way, isn’t it? Because when we have a piece that has some complexity, some go-faster stripes, part of you wants to show off how neatly you can do it at speed.

“But some pieces, which could be played in a complex, fast way, actually breathe a bit more and sound better when you let a bit of air and space into them. So I suppose it’s a matter of taste and experience judging where to pitch it. It’s maturity, really, but it takes a long time to get to that point. It can take a lifetime, actually.

Any guitar player worth their salt would love to be able to play as well as Tommy does night after night, with that speed, with that precision. But, for me, it’s the slower pieces that he plays that mean more…

“Let’s take as a shining example the brilliant Tommy Emmanuel. Any guitar player worth their salt would love to be able to play as well as Tommy does night after night, with that speed, with that precision.

“I’m never going to be able to play like that. But, for me, it’s the slower pieces that he plays that mean more… So I’m a shining example, if you like, of somebody who can play something slower – hopefully something that’s got a bit more melodic, emotional and soulful content to it, that means something. For example, every track on this album means something, there’s a story behind it.

“But let’s take any great guitar player: no matter who they are, throughout history, they’ve not become great because they played fast. If you analyse it, why is Peter Green still revered as this great guitar player? Was Peter Green a fast guitar player? So why are these people great? Because you are touching the soul. You’re making a direct contact between you and their soul, which is a deeper level. And it’s so deep at times you can’t even put it into words.

Let’s take any great guitar player, no matter who they are, throughout history, they’ve not become great because they played fast

“Let’s take Jeff Beck: Jeff Beck can play three notes and it makes the hair on the back of your neck stand up. His sound, his tone… I mean, when the penny really dropped with me about Jeff Beck was years and years ago. My drummer at the time, Ian Mosley, gave me an album called There And Back.

“There’s a track on it called The Final Peace – just Tony Hymas on keyboards and Jeff on guitar. And that first note when he came in… it feels like you’re listening to God. And that’s what he was trying to create. Just that tone, that sound and his fingers on that fingerboard was just incredible. That’s genius. Peter Green could play just three notes like that. Because he was playing from the heart. It’s just beautiful.

The other insecurity guitarists can fall prey to is feeling that their gear isn’t good enough.

“Yes, I remember the early days of Guitarist magazine where they would interview me and I would think, ‘I saw that interview with David Gilmour and he’s surrounded by all these guitars. Now, if I’m surrounded by a lot of guitars people will think, ‘Oh, he’s successful – he’s got all those guitars. I wish I was him.’ And it’s all bollocks.

“It’s all absolute bollocks. But we’re still looking for that guitar, aren’t we? We think, ‘If I buy that guitar, I’ll be a better guitar player,’ or ‘If I buy that guitar I can write better tunes.’ Now, there’s still that within me – I mean, I’m still looking for a guitar that I can use to help me create better music. But, in actual fact, I don’t need to.”

You had a period of serious illness a few years ago – how did that affect your relationship with the guitar?

“You know, I’m very blessed. I mean, in 2015, I could have died, you know, I was diagnosed with cancer. It wasn’t till 2016 that I could have surgery, but anything can happen. I could have died under the knife, but I didn’t. I came through that. I subsequently had to have more surgery.

“For all I know, I may need to have more surgery, but you just think, ‘Well, okay, I’ll just take that as it comes’ – though that’s easier said than done because fear is a big obstacle to get over. But I had a little wonderful moment the other day when I was doing my meditation and, suddenly, I thought, ‘I’m not scared of anything.

“Whatever comes my way, I’ll deal with it.’ Because there’s nothing you can do about it. They say, ‘Everything you resist, persists.’ You can’t go against the flow of life, you can’t go against what’s going to be happening to you. You can’t avoid it, so you try to deal with it the best you can.

“But when I became ill, I lost all interest in music and I would go into my music room and I would sit there surrounded by all these guitar cases. I’d know that I’d got the finest guitars in the world in that room. I had a beautiful J-200 that Pete [Townshend] gave me when word got back to him I was poorly. And I’d always hankered after a J-200, so there I was and I thought I got a guitar that was given to me by Pete…

“In fact, within a month, I was given two guitars, one from Pete Townshend, one from Brian May – Brian gave me a beautiful little 12-string, which I’ve recorded with and I used it on one of the tracks. But I was sitting there thinking, ‘I’ve no desire to pick up anything. I’ve got no desire to play, I’ve lost all interest in music. Because the fabric of my life has just been ripped away. Somebody’s just told me that I’ve got something serious that can be life-threatening.’ So you start questioning your mortality and you get things into perspective.

When I became ill, I lost all interest in music

“But as time goes on, you start to take interest again and start playing again and thinking, ‘Will I ever get back to playing on the stage again? Will I be well enough?’ But Johnny Etheridge said to me, when I told him I was ill, ‘After you’ve had your surgeries your job is to get better. That’s your job, nothing else. Your job is to get better.’ That stuck with me because he’d had major surgery a couple of years prior to that.

“We all fall into that trap of [endlessly acquiring] guitars, you know, but they are only things… And at the end of the day, whatever guitars we buy or sell or keep, we’re only custodians of them. We’re only borrowing them – it’s like the house we live in. We only borrow it.”

How do you hope the songs on Scattered Chapters will be received, when viewed against the big picture of your life in music?

“When you know the backstory to a piece and somebody says, ‘I’m not really keen on that piece,’ I’ll say, ‘That’s fine, as a matter of opinion – but I know where it’s come from. I know what it means to me, and I know what it means to Paul.’ And that’s why this body of work is so powerful.

“I could never, ever come up with anything that can improve on this album; it’s not possible. Just like with Troubadour, it’s not possible to make a better album than that because you can’t replicate the energy and the atmosphere and the vibe of what was happening at that point in time, when you’ve got the great Del Newman conducting some of the finest musicians in the country, many of whom have passed on now…

“So when I’d done that album, I thought, ‘This is my finest album, I can’t do better.’ But then if you start going back in time to Visionary, The Perilous Journey, Fear Of The Dark… you remember the vibe in the studio at that time, where you had the finest drummer in the world playing on your tracks, Simon Phillips. So you go, ‘That was then, this is now – let’s move on.’

“There’s no way that Paul and I can make a better album than Scattered Chapters. Paul said, ‘I think the best is yet to come.’ But no, that’s not true. All we can do is the best we can do, in the future, if it’s right for that to happen and if the circumstances of life allow us to do that. Because tomorrow doesn’t exist. The future doesn’t exist.

“You can talk about it. You can plan it and you can put it in the diary. But it only happens when you get there. If you get there. But I have to tell you, every track on the new album was written from the heart. And I apply that to anybody who writes something.

“I say, ‘If you’ve written something from the heart, if you put it out there in the public domain, people are going to make a comment.’ But if you’ve written it from the heart, that’s all that matters. At the end of the day, you know where it’s come from. You don’t need to change a note of it. Because you’ve got to live with that.”

- Scattered Chapters is out now via Psychotron.

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.