All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

There was a piece piece of tape on the rehearsal studio floor where, in the past, Izzy Stradlin’s amp would have been. “And on the piece of tape,” Gilby Clarke says now, “and I’ll never forget this, it said, ‘Do you have what it takes to fill this spot?’“

Clarke had what it took. He’d walked in that fall 1991 day with a Les Paul and Marshall half-stack to audition for Guns N’Roses’ rhythm guitar spot, which Stradlin vacated following a tour leg supporting the Hollywood hard-rockers’ Use Your Illusion albums.

Clarke’s three-year tenure with the band would include GN'R’s most legendary tour and two un-legendary Guns N’ Roses albums, The Spaghetti Incident? and Live Era ‘87 - ‘93.

For such a huge band, these albums, particularly the latter, are close to being forgotten. Lost in the shuffle amid savagely brilliant debut Appetite for Destruction, controversial GN’R Lies, sprawling Use Your Illusion and mythologized/maximalist Chinese Democracy.

Still, Era is an underrated concert album that remains the band’s only official classic-era live disc. It displays why GN’R was powerful enough to (partially) reunite in 2016 and play stadiums and arenas across the world – something they’re still doing, more than 25 years after their heyday.

Punk-covers effort Spaghetti contains some feisty gems. It’s admirable that Guns followed up the grandiose Illusion twin-towers by returning to their street-band roots.

Spaghetti Incident? and Live Era were both released November 23, six years apart, Spaghetti in 1993 and Era in 1999. As far as GN’R goes, that period’s typically remembered for the band splintering to where singer Axl Rose was the lone classic-era member.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Rose’s relationship then with snake-haired guitar-hero Slash was acrimonious at best. As far as albums go, neither Spaghetti or Era are Appetite-essential. But the Guns N’ Roses story isn’t complete without them.

The middle position between the humbucking and single coil was kind of magical. On Sweet Child O’ Mine during the verses and all that, that’s always the middle

Gilby Clarke

Even amid the daring hard rock, stadiums and drama that was early Nineties GN’R, their new guitarist wasn’t on a leash.

“I was never once told what to play and not to play. Ever,” Clarke says, calling from his San Fernando Valley home studio. “But I could always tell if it didn’t work. Slash would just look over like, ‘What the hell was that?’ [Laughs] You could tell if it caught his attention in a good way or in a bad way.”

Clarke’s GN’R audition took place at Third Encore Studios in North Hollywood. Slash had called him around midnight to come in the next afternoon. The first time Clarke – as a member of GN’R – heard Rose sing with the band was onstage at Clarke’s first show with them, December 5, 1991, in Worcester.

Songs like Patience were always great to play. I loved that song the first time I ever heard it

Clarke played guitar on 16 of the 22 tracks eventually culled for Live Era. (This makes it even more dubious that he and Sorum are credited as “additional musicians.” Clarke says, “It wasn’t that funny at the time, but now it’s kind of funny.”) Clarke-era highlights on Era include razor-wire tangle on Nightrain, an explosive It’s So Easy, tribal-metallic You Could Me Mine and legitimately epic Estranged.

After getting the gig, Clarke hit the ground running. The Cleveland native was asked to learn GN’R’s entire catalog, 50 tracks, in two weeks.

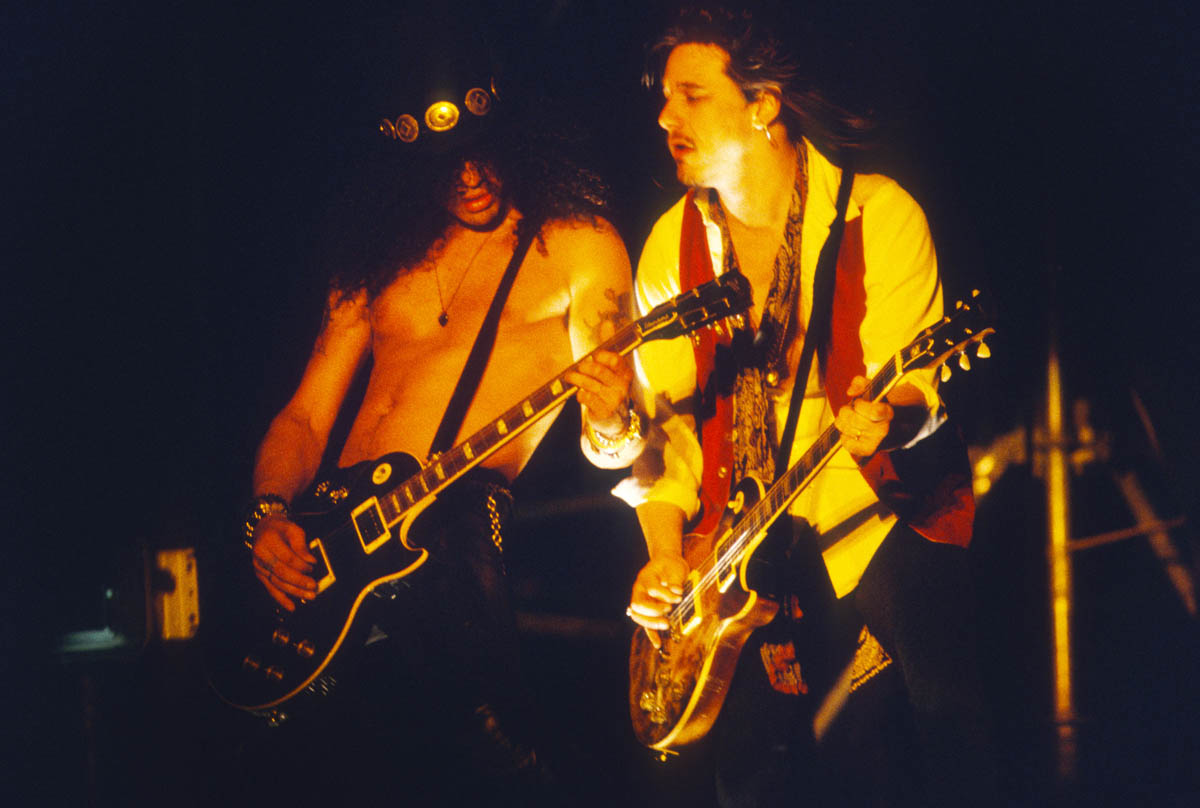

His Illusion tour guitars included a late-Seventies black Les Paul Deluxe with full-sized Seymour Duncan humbuckers, ’91 Les Paul Classic with “burnt” finish; and a couple of Telecasters, including a red Tele with a humbucker in the bridge.

“The middle position between the humbucking and single coil was kind of magical,” he says. “On Sweet Child O’ Mine during the verses and all that, that’s always the middle, songs like Don’t Cry.”

Slash’s live guitars for Era recordings included 1984, 1987 and 1992 Gibson Les Paul Standards, ’87 goldtop, ’75 Gibson EDS-1275 doubleneck, B.C. Rich Mockingbird and Guild Crossroads doubleneck.

According to Slash Paradise, his amps during this era included Marshall JCM2555 Silver Jubilee heads with EL34 tubes and Marshall 1960BV 4x12 cabinets.

I loved what Izzy and Slash did, especially on Appetite. They played off of each other. It was like an Aerosmith thing, and Aerosmith are just a louder version of the Stones

Clarke started his GN’R run using 50-watt Marshall JCM800s. About a year in, that changed. “At times Slash and I would hit a chord and I couldn’t really tell who hit it,” Clarke says with a chuckle. ”So, I switched over to Vox AC30s.”

On the road, Clarke was listening to albums by Bash & Pop, Mazzy Star and Stradlin’s solo debut, Ju Ju Hounds. He’s the first to give his GN’R predecessor credit.

“I loved what Izzy and Slash did, especially on Appetite. They played off of each other. It was like an Aerosmith thing, and Aerosmith are just a louder version of the Stones. I tried to take what Izzy started and just add to that. I don’t play with as much gain as Slash has, but I play with more gain than Izzy does.”

Of Stradlin-period recordings on Era, a stomping You’re Crazy and Some Girls-ish Used to Love Her standout. Clarke says he only listened to the album once when it was released.

“At that time, it was a little Guns N’ Roses overdose for me. But I definitely have my memories of playing those shows. Songs like Patience were always great to play. I loved that song the first time I ever heard it on MTV or whatever, and Axl always sang it well.”

He was also fond of Welcome to the Jungle, and there’s a hot, ’92 Buenos Aires version on Era, “because as soon as the riff started no matter where you were the audiences just went nuts.”

I would pick the longest songs that we weren’t singing on to go to the bathroom, because in these big arenas the bathrooms are golf cart rides away

Roberta Freeman

There were makeshift dressing rooms beneath the expansive Illusion tour stage. This is where backing vocalists Roberta Freeman and Traci Amos would sit, drink, play cards and hang.

They sang on only about 12 or so songs and GN’R played around 20 each night. Since the band operated sans setlist, the singers didn’t know exactly when they’d be needed.

“All of a sudden we’d hear the intro to Paradise City and have to run up onstage to get to the mic on time,” Freeman tells us. “I would pick the longest songs that we weren’t singing on to go to the bathroom, because in these big arenas the bathrooms are golf cart rides away.”

Freeman and Amos added to GN'R’s wallop, particularly on Southern-rock-gone- Sunset-Strip anthem Paradise City. They gave wah-wah dominatrix dervish Pretty Tied Up extra pepper.

Freeman wasn’t a stranger to loudness. She’d grown up on rock ‘n’ roll like David Bowie and just got off tour with Cinderella. Cinderella drummer Fred Coury recommended Freeman to Slash, who’d mentioned Rose wanted backing singers for GN’R. (He wanted an all-female horn section too, which birthed the 976 Horns.)

Freeman notes Cinderella singer/guitarist Tom Keifer and Rose “have similar voices when they went into their falsettos.” Still, Guns N’ Roses was a different animal, she says. “With Cinderella we rehearsed a million times. With Guns you never knew what to expect.”

With Cinderella we rehearsed a million times. With Guns you never knew what to expect

Roberta Freeman

When Freeman was hired, Slash asked her to do vocal arrangements for the tour. “I had the artistic freedom to arrange whatever I wanted for the live shows, and I enjoyed that a lot,” she says. “I basically went with what just felt natural.”

Her favorite singers include Aretha Franklin, Chaka Khan and Stevie Wonder. When it comes to the ultimate use of backing vocals by a rock band, “I think of the Stones, hands down,” Freeman says.

Freeman liked singing GN’R’s gospel-metal Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door cover best. Freeman and Amos helped sanctify choruses. Freeman was also given a feature. “Close to the end of the tour, Axl told me he looked forward to my solo every night,” she says.

Heaven’s Door also contains Era’s most notorious moment, when Rose implores the band mid-song to “Gimme some reggae!”

The air was electric, even for recording engineer Jim Mitchell, who’d worked on the Illusion albums and recorded much of what became Era. “It was a huge rush when those guys would take the stage,” Mitchell says in his Boston accent. “They were playing with reckless abandon, and you can really hear it on that Live Era album.”

If it was a softer part where Axl wasn’t pushing a lot of air and he’d run past Slash’s rig, you’d get this roar of Slash’s amp blazing into his vocal mix. That was a tricky thing to balance

Jim Mitchell

GN’R rarely soundchecked. As a standin, a makeshift band including guitar tech Adam Day would help Mitchell out, by checking their song called Crackpipe.”

Six performances from a ’92 Tokyo Dome show, including a vamped-up Move to the City, are an exception, as Guns soundchecked before the show, also filmed for home video, “so they did some camera blocking,” Mitchell says.

In Tokyo, Mitchell was stationed inside a truck that was parked behind the stage. “Back then the stage volume was insanely loud,” he says. “Under Matt’s drum riser he had like four 18-inch subs, so when he hit the kick drum it would literally lift you off the drum stool.”

Mitchell recorded to 2-inch analog tape. GN’R had him at a ’92 Las Vegas show, a performance of their Rod-Stewart-in-Spandex hit Yesterdays for the American Music Awards. “It was like, ‘While we’re here we’re going to record the whole show,’” Mitchell says.

I thought Slash evolved a lot from the time Appetite came out to when the Illusion tour started

Gilby Clarke

Slash’s playing on Era, heard through the side-right channel, ranges from gutter-funk (Mr. Brownstone, London ’91) and sinister gashing (It’s So Easy, Paris ’93), to space-cowboy runs (Patience, Mexico ’93) and bulbous melodies (November Rain, Tokyo ’92).

“I thought Slash evolved a lot from the time Appetite came out to when the Illusion tour started,” Clarke says. “He had a guitar in his hotel room and was always playing and practicing.

“Look, there was a lot of partying going on during the live shows and stuff and we definitely were guys enjoying what was there. But one thing about the band was everybody took the music very seriously. Nobody wanted to let each other down.”

As an intro to November Rain on Era, Rose plays a snippet of Black Sabbath’s “It’s Alright,” just vocals and piano. It’s a small, soulful moment on a big stage. It’s also probably the first time many young Guns N’ Roses fans heard that Sabbath obscurity.

The Spaghetti Incident? was definitely the first time mainstream fans heard songs by punk bands like Fear and UK Subs.

Basically this was GN’R’s version of Metallica’s Garage Days Re-Revisited. Guns recorded much of Spaghetti during Illusion sessions, and Mitchell recalls most of the former being tracked at the Record Plant on Sycamore Street in Hollywood.

“It wasn’t like, ‘Oh we’re set up, let’s blow off some steam and do some punk covers,’” Mitchell says. “We specially set up, and they had these songs they wanted to do.”

Dead Boys cover Ain’t It Fun contains one of Mitchell’s all-time favorite Rose vocals. The GN’R frontman sang it as a duet with Michael Monroe.

It wasn’t like, ‘Oh we’re set up, let’s blow off some steam and do some punk covers. We specially set up, and they had these songs they wanted to do

Jim Mitchell

The former Hanoi Rocks frontman was in town to play harmonica and sax on Illusion boogie Bad Obsession. After Rose mentioned he’d never heard Dead Boys’ music, Monroe taped a cassette for him. After hearing dark intense track Ain’t It Fun, Rose wanted to cut it with GN’R and invited Monroe to guest.

Monroe was close friends with Dead Boys frontman Stiv Bators, who died in 1990. Monroe didn’t want money for the session. All he asked for was “In memory of Stiv Bators” in the credits, which GN’R honored, “and spell my name right,” he says with a laugh.

We sang it face-to-face live, and there was a magical vibe, almost eerie. Stiv’s spirit was definitely present

Michael Monroe

Rose was the first member of Guns Monroe had met, when Rose happened to be in New York and walk by a video shoot for 1989 Monroe solo track Dead, Jail or Rock ‘N’ Roll.

Bators had a studio ritual of lighting candles. Monroe asked Rose if they could do the same and Rose obliged. “We sang it face-to-face live, and there was a magical vibe, almost eerie” says Monroe, calling from his home in Finland. “Stiv’s spirit was definitely present.”

In the mix, Monroe’s vocals are panned left and Rose’s are panned right. It’s a mesmerizing track. After singing, Monroe went to the back of the studio to wind down a little.

The lounge was stocked with pinball machines and as Monroe sat down, the machines suddenly lit up and clanged. Monroe said to Rose, “Maybe Stiv just got his wings, like in It’s a Wonderful Life?”

After the 1985 breakup of Hanoi Rocks, a group that influenced many Hollywood bands, including GN’R (while never having a big hit in the U.S.), Monroe moved to London.

When Bators would tour, Monroe took care of his cat, Ziggy. Eventually Monroe moved into the flat too. Later, former New York Dolls guitarist Johnny Thunders moved in with them.

“There was never a dull moment,” Monroe says. “Stiv and Johnny really helped me through that time Hanoi Rocks was breaking up. They were special people. And two of the most unsung heroes that really had what rock ‘n’ roll was all about to me – no compromise, never sold their soul.”

Other Spaghetti apexes include a hellacious Human Being that surpasses the New York Dolls prototype, and sidewinding Sex Pistols cover Black Leather.

Izzy really didn’t play on any of that stuff. Some of the stuff he wasn’t there for, and even if there was something, you could hear in his playing he wasn’t into it

Gilby Clarke

With Stradlin out, Slash asked Clarke to do a session with GN’R producer Mike Clink adding Clarke’s rhythm guitar to Spaghetti. Clarke had just one day to do overdubs. Without rough mixes in advance, he had to figure out his parts and knock them out on the fly. Before digging in, for reference he asked to hear what Stradlin tracked.

“We put it up, and Izzy really didn’t play on any of that stuff,” Clarke says. “Some of the stuff he wasn’t there for, and even if there was something, you could hear in his playing he wasn’t into it.”

That day, Clarke played a Seventies Les Paul (its back adorned with stickers from his previous bands, Candy and Kill for Thrills) and custom guitar by British luthier Tony Zemaitis, whose striking designs were made famous by Rolling Stone Ronnie Wood.

Before crafting Clarke’s guitar, Zemaitis traced his hand so the instrument would fit perfectly. “I always say my Zemaitis was like the best Les Paul ever made. That guitar just rang and rang.”

For Spaghetti overdubs, Clarke stood in the control room with Clink and a long cable ran out to his ’62 Fender Deluxe amp in the tracking room. Clink was integral to shaping GN’R’s sound, but rarely does interviews, so his mojo’s somewhat mysterious.

“The thing about Mike is honesty,” Clarke says. “With Guns N’ Roses’ success at that time a lot of people could be intimidated. Mike was not intimidated. Every person in the band respected Mike’s opinion, so if he thought it was a good take or you could do better you trusted that.”

Spaghetti’s opening track, a take on the 1958 Skyliners doowop ballad Since I Don’t Have You, was cut on the road. “Axl had played it like as an intro to one of the shows or something like that,” Clarke says. “He was into the song and wanted us to learn it and record it.”

Because GN’R’s gear was shipped from gig to gig, “we literally showed up at a studio in Boston on rental amps, rental guitars, rental everything.”

Clarke got the idea to lay down acoustic guitar for Since I Don’t Have You, with one of Slash’s most tastefully elegant solos. “I just remember my fingers being really sore,” Clarke says. “And a little bloody too by the time we were finished with it.”

Way before I was ever in the band, I always thought they reminded me of Nazareth

Gilby Clarke

Spaghetti’s most accessible rocker is a hot version of Nazareth riff-fest Hair Of The Dog. During a kick-and-cowbell intro Rose asks, “Give me a little bit of volume on this,” before soulfully shredding his throat. “Way before I was ever in the band, I always thought they reminded me of Nazareth,” Clarke says.

As Slash says in a circa-’93 MTV interview, GN’R’s original covers concept had veered off-script: “It wasn’t a punk record so much anymore, it was a Guns N’ Roses compilation of songs we were into and bands we were into when we were coming up.”

Spaghetti’s liner notes included this message to fans: “Do yourself a favor and go find the originals.” But the LP’s most curious song isn’t listed – a version of Look at Your Game, Girl, a hippie-folk tune by convicted cult leader and psychopath Charles Manson, which was included as a hidden track.

Mike Clink was not intimidated. Every person in the band respected Mike’s opinion, so if he thought it was a good take or you could do better you trusted that

Gilby Clarke

Brian James learned GN’R had cut a version of New Rose, the Damned’s whirlwind 1977 single, by reading an interview with Slash. James was the horror-tinged British band’s original guitarist and penned the song, creating New Rose on a Sixties Gibson SG.

Around that time, he was listening to a lot of MC5, Ramones and Stooges, whose Raw Power is covered on Spaghetti. James is fond of GN’R’s New Rose, with McKagan singing lead, for a couple of reasons.

“I was pretty broke, to be honest,” James says, “and it was at a time when I wanted to leave England and move to France, and having that money from Guns doing (the song) was really useful. Apart from that, they’d done a good version. It’s straight-ahead, it’s tough. The way the song should be. I’d heard other versions and they just didn’t measure up.”

Why haven’t Spaghetti and Era connected with fans like Appetite or even cult-fave Chinese Democracy? At the time Era was released, it seemed like an afterthought.

“I feel like it was one of those things,” Mitchell says, “that didn’t get the full weight of the machinery behind it, meaning the label promoting it and getting it in the front of the stores and at radio stations and TV.”

Plus, Axl’s rebooted GN’R and Slash had gone their separate ways, so it’s likely neither was psyched to promote it. Era was certified gold, a coup now but at the height of CD sales not so much. Spaghetti reached Number 4 and went platinum, but during an alt-rock goldrush, GN’R didn’t quite resonate like before.

It was obviously Axl and Slash’s band, there’s no question about that. But it still felt like a band

Gilby Clarke

Still, those involved with Spaghetti Incident and Live Era have fond memories. Mitchell, who now does lots of NFL TV work, marvels at Slash and Day’s teamwork to replicate studio tones onstage for Era. “It’s seamless stuff but makes a huge difference,” Mitchell says.

Although GN’R wasn’t on Freeman’s personal playlist before touring with them, she says the band “turned me into a believer.”

Monroe, who just released a solo LP, One Man Gang, will never forget how GN’R made it a point to mention Hanoi Rocks in interviews, “unlike some other bands who tried to copy Hanoi, but were more into posing and missed the whole punky attitude and the street-gang vibe.”

In 2017, James went to see GN’R’s London show. The band performed New Rose. James says, “Duff in particular, his heart’s really in the song, and that really shows.” This year, Clarke will release a solo album, The Gospel Truth, featuring backing vocals from Freeman, who also appears on Weezer’s 2019 Black Album.

After GN’R, Clarke worked with the likes of Heart, MC5, Nancy Sinatra and Slash’s Snakepit. He’s done just fine. Still there’s something he misses about the days captured on Spaghetti and Era.

“It was obviously Axl and Slash’s band, there’s no question about that,” Clarke protests. “But it still felt like a band – like Slash would ask me questions, ‘What do you think about this?’ and he listened. Same thing with Axl. I knew my place in the band and how long I’d been in it compared to everybody else… but it really felt like it was yours.”