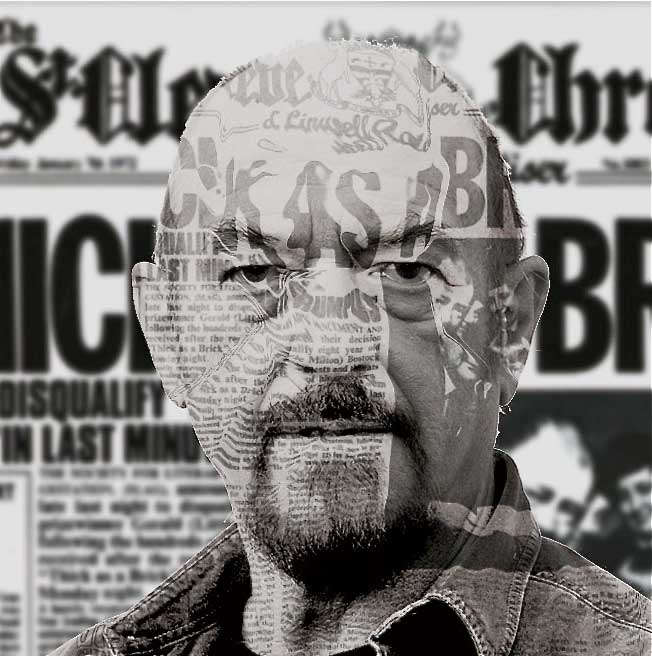

Interview: Jethro Tull's Ian Anderson Discusses Gear and 'Thick As A Brick 2'

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Last year, Ian Anderson took Jethro Tull on tour to commemorate the 40th anniversary of Aqualung, one of the sacred stones of classic rock.

This year, not only is he revisiting another of his crown jewels — 1972’s Thick as a Brick — he’s cut a feature-length sequel and will spend the next year or more putting it on the road.

With musical nods to the original and a few other classic Tull riffs, Thick as a Brick 2 returns to the fictional “star” of Thick as a Brick, Gerald Bostock, a precocious schoolboy whose “inappropriate” poetry was banned from a local contest, but later put to music by Jethro Tull, forming the epic title cut that spanned both sides of its original vinyl pressing.

The sequel, which dropped on April 3 in the U.S., presents Anderson wondering aloud how Gerald’s life might have turned out, giving us many different possible outcomes, from an overpaid banker to a corrupt Christian evangelist.

A few days after the release, and a few weeks before his European tour begins, Anderson spoke about TAAB2 (his pronunciation), putting together a theatrical show, Andy Manson guitars and successfully landing a Boeing 737 — twice — despite never having been licensed to drive a motor vehicle.

GUITAR WORLD: Thick as a Brick was a parody. What about Thick as a Brick 2?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

It [Thick as a Brick] was supposed to be fun and a bit of a send-up of the concept album, prog-rock style of ’72, ’71, whenever … it was relatively light-hearted, although there was some rather dark sort of child-fantasy moments in the lyrics. Overall it kept the spirits of parody, of spoof, in the style of surreal British humor, I suppose going back to the ’50s, certainly into the ’60s. It was very British.

With TAAB2, I’ve continued that element of the approach in terms of St.Cleve.com, the online newspaper (the famous cover art of the original was the front page of the St. Cleve Chronicle “newspaper” and its story about Gerald), but lyrically speaking, TAAB2 was less overtly spoof-like. I’m not writing this as an 8-year-old boy. I’m writing this as a 63-year-old man, which I was when I wrote it.

You’ve been working on the TAAB2 album for quite a while already and will be touring it into next year. That’s a long time. What is motivating you to make such a lengthy commitment to this?

Well, it’s important enough to tackle a big project while I’m able to do it because, in reality, I shall be 65 years old, possibly 66 by the time we finish doing this concert tour and series in 2013. I’ll be back in the US in June of 2013 and I’ll be coming up on 66 then. That’s OK, but best to do these things now while I’m physically able to do that sort of thing.

I mean, five years’ time, goodness, I’ll probably not be able to take up such a big chore. Who knows? But what I do know is it’s physically as well as mentally quite demanding, doing two hours of — I was actually counting it up in rehearsal yesterday, being it was the last day of rehearsal — I think there are about 16 bars in two hours of music when I’m not actually playing or singing.

That can’t be easy.

And it’s not easy music to play. Some of it is easy enough, but it’s really remembering what comes next. You have to remember all your cues, all your effects settings, remembering what fret to put the capo on. There’s nothing worse than the train wreck of starting a song in the wrong key.

And you’ve got a whole theatrical show to go along with the music?

It’s a theatrical small show. We’re not out there doing laser beams and dancing girls. It’s not a Madonna on tour, or a Michael Jackson tour that never was. These days we have the benefit of technology, audio visual stuff, so there’s lots of things that we include in the show that are human interaction with each other, with the audience, as well as audio-visual interaction with the audience.

So yeah, there’s a lot of elements there that make it considerably more than just standing on stage playing the music, and for most of the tours this year, that’s the way it is. There are some dates in the summer, there are a few outdoor festivals and you simply bring all that equipment and set it without seven or eight hours of prep. … But all the tours, the major European tours and the two U.S. tours in the fall, they are the full-production tours. … We treat it more like a bit of musical theater.

You certainly have put a great deal of effort into presenting visual shows in the past, particularly during the peak years for Jethro Tull. Do you enjoy being a showman as much as a musician?

Yeah, it’s fun to do. It’s a little dreary doing it over and over again in rehearsal because you get to the point ... it feels rather pretentious when you doing this thing when there isn’t an audience there. But when we step out in front of an audience next week for the first time, it will be altogether more a jelling experience.

I enjoy doing it but there are places where I have to stand pretty still and play the music because it can be very demanding. You’ve really got to be visually in contact with the other band members for all the little nods, winks and cues we give each other, especially in improv sections.

I’ve listened to TAAB2 twice now and I’ve enjoyed every minute of it. It sounds great.

If you liked every minute of it twice, you’ve enjoyed 107 minutes so far! It’s quite a long album. When I cut it on vinyl a couple of weeks ago at Abbey Road Studios in London, it was one of the longest vinyl albums that had been cut. It was amazingly successful. I was completely surprised by the quality we got. Not just the quality, the level on the disc was pretty good.

We actually will be cutting it on a copper master rather than an acetate master or a lacquer master because we can squeeze an extra half db of level or so onto a copper master. And it will be hopefully as good as I heard it the other day when I compared it to the 24-bit digital audio. It was almost indistinguishable. Which was amazing in terms of today’s technology, to be able to go back and do the old-fashioned vinyl thing and get it to sound so.

When does the vinyl release come out?

In September, TAAB 1 and 2 will be released together as a vinyl package.

In addition to revisiting Gerald Bostock and the St. Cleve Times, you revisit certain musical themes in TAAB2. You can hear it in the very beginning and in several other tracks, including “Old School Song.”

When I set out to write the new album, which was in January-February of last year, I tried to earmark three or four places where I could make a reference to the original album. And we extended that, lyrically and musically combined, into maybe five nods and winks to the old TAAB album and actually a couple of references to Aqualung, even to A Passion Play. Yes, of course, I put those things in there, they’re little moments really for a listener, a fan, to spot. Some people may spot them. Some may not be so perceptive. It’s just there to give that kind of anchor, that bit of a reference.

But I didn’t set out to make a nostalgic return to a previous era. The whole premise of this album is it is 2012, a current-day set of possibilities in terms of what might have become of the young Gerald Bostock late in life. It jelled for me as an idea when I suddenly got the notion, “I wonder what Gerald Bostock would be like today? What would the St. Cleve Chronicle be like today?”

Those two ideas were the whole essence of using the character of Gerald Bostock as a vehicle to get us quickly from 1972 to 2012. Look at the differences that had become very apparent in life today as opposed to 40 years ago. And in one or two cases, you know, some of the things that haven’t really changed in 40 years, as we prepare to exit Afghanistan, and in 1972, we were, or you guys were, preparing to exit Vietnam. So the echoes of imminent, and probably tail-between-the-legs departures, from theaters of war, there’s an uncanny echo in today’s final winding down of what is proving to be an unsuccessful adventure.

Of course, you’re known for being out front with your flute, but you play a lot of acoustic guitar. So can we talk guitars?

I was just trying to remember when I was restringing one of my guitars this morning and I was preparing it to take on tour and thinking, “Wait a minute, is this the one I played on the record, or did I play the other one?” Because I have two guitars which pretty much look identical.

One was made by Andrew Manson about 16 years ago. It was made basically on a template that I sent. Andy’s made a few guitars for me and John Paul Jones and various other people over the years. I sent him a template with all the dimensions written down, for a three-quarters-sized parlor guitar, based loosely on an old French parlor guitar that I own — I don’t play, it’s a wall hanger, I mean pretty wall-hanger, but being from the 1860s, it’s not really practical to play onstage — and so I took that as a model, scaling down a guitar that was a bit bigger than a travel guitar, but not much.

I was building a guitar for a purpose, because the airline regulations are increasingly becoming different, the maximum sizes they will allow you to bring on board. … I use a double rifle case because it fits my travel guitar and it also takes a spare flute, my radio gear, spare strings and a bunch of other bits and pieces, all neatly sandwiched into a travel-able case with wheels and a handle. So the guitar was built to fit what I could acquire that was airline-legal at the time. The overall length of the guitar means the actual bridge sits closer to the end of the guitar than would normally be the case to get a good acoustic sound. But these are all compromises that you have to make.

You said you have two of these guitars?

One by Andy Manson. Then Andy Manson gave up making guitars a few years ago, decided he had enough, so the molds went off to Brook Guitars … the guys there trained with Andy Manson some years ago, so they made me more or less a clone of the original guitar.

Which means that during the last three or four years, I’ve had two guitars to choose from … (laughing) and I cannot remember which one I played on the record now. I’m at that point that I played a lot on both guitars this morning and I’m still yet to make a firm decision which one to play. The neck dimensions are always a tiny bit different. The feel, the action, the setup, the sound are all ever so slightly different. It’s rather like flutes, you pick them up on consecutive days and you change your mind which one sounds the best.

How do you amplify them on stage?

These guitars are fitted with Fishman Rare Earth pickups, which are magnetic pickups [that] also have a built-in, attached gooseneck microphone that sits in the guitar. That’s what I use for onstage amplification. Indeed, I’ve used Fishman transducer pickups since they first appeared and I’ve used them on my guitars and mandolins for many, many years. Currently for the kind of music I’m playing, with a lot of single notes involved, the magnetic pickup with the built-in mic is the best option for me.

Who are your primary influences as a guitar player?

I suppose when I started playing guitar, it was the means to an end. I never thought of myself as a fully fledged guitar instrumentalist. And my early excursions on the electric guitar were curtailed when Eric Clapton came on the scene and I decided I was never going to be in the same arena as a Clapton, or a Peter Green. That prompted me to look for something else, which on a whim turned out to be the flute. But the guitar, once I started playing the flute, I equipped myself with an acoustic guitar, which I could carry around with me. I didn’t play it in the early days of Jethro Tull.

I took it with me in order to write songs. I can remember writing the songs for our second album, the Stand Up album, at a time when I didn’t have a bona fide acoustic guitar. I was playing on a beaten-up, barely audible Harmony Stratotone, which may be known only to the most anal readers of guitar magazines. Which was a very light hollow-body electric guitar, not a true acoustic guitar, but a single cutaway hollow-bodied electric guitar, which you could just about hear.

I subsequently got a Yamaha folk guitar, a small-bodied folk guitar, which led me in my quest to find smaller- and smaller-bodied guitars. For many years I played Single-O Martin guitars onstage. And while I still do play my Martin guitars, I have a lot of vintage guitars. From 1835 is my oldest model. The ones I love are the size 2, 2 ½ parlor guitars.

I have a few Martins [from the] late 1800s, which are my favorite guitars. But they’re very lightly built and they were obviously built then for gut strings, or nylon strings these days. And a couple of them I’ve had the fitted with Fishman transducer pickups, so they are playable in amplified context. But they have such a fine and delicate sound. They’re strummers and not pickers. And because my music, as a guitar player in JT or doing my Ian Anderson shows, either way, it’s a mixture of single-note picking and more rhythmic strumming with a pick. And that’s never quite so successful when you us nylon strings. So I stick to steel-strung guitars when it comes to doing stage performances. I’ve used nylon-string old Martins a few times on solo albums when playing lines that were more of a finger-picking thing.

But I haven’t answered your question about the people who enthused me as a young acoustic guitarist. This takes us back to ’68, and probably would be Bert Jansch, Roy Harper, those guys more than anything else. I like the way in which there was a way to join the more folky finger-picking style with a more rhythmic playing, and that was one of the things that Roy Harper did particularly well. We did a few things together, not actually playing together but on the same bill, and I was able to watch him playing first-hand, so that was probably my main influence.

But as a songwriter, you tend to develop your own style, your own technique, based around what it is you’re trying to write and perform, in terms of your own music. So a way of evolving a guitar style as a songwriter is much easier, I think, than developing a true style of your own just form listening to music or playing other people’s music. I think those who write their own music are the ones who have the most creative, and often very quirky, ways of developing a performing style. Certainly, I’ve never had a lesson either in flute or guitar, or driving a motorcar, for that reason.

I heard you’ve never got your driver’s license.

I did have a lesson the other day, though, in driving something. But it was a Boeing 737 400 series flying out of Heathrow Terminal Five. I’ve never flown an airplane before. It was quite interesting, sitting on the cockpit of a 737 400, with a very pregnant copilot sitting next to me, and assisting me in staying in the air and making not one, but two, successful landings. The second (laughing) much better than the first.

And this is what airline, just so I know for my own safety?

(Laughing) By the time I got out of the British Airways flight simulator at Heathrow Airport, we were all quivering, legs like Jell-O. I didn’t crash it. It was a proper flight simulator, a real airplane. Everything moves, hydraulics everywhere, so you feel every sensation in the cockpit, including if you were to crash. In fact, usually people who attend flight-simulator courses have to produce medical proof that they are physically not going to suffer from cardiac arrest.

So you are open to being taught a lesson.

But that’s about it. Guitar lessons? Nah. There’s not a chance of that.