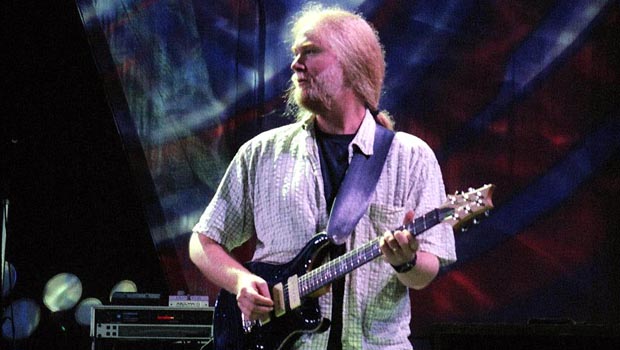

Interview: Jimmy Herring Discusses Influences and Incorporating Outside Sounds into His Playing

Jimmy Herring is a stunning jazz/rock virtuoso.

Though his resume includes touring with classic rock legends The Allman Brothers Band, fusion icons Lenny White and Billy Cobham, and jam staples The Dead and Widespread Panic, he has remained relatively unknown within the guitar community.

Herring’s mix of fluid fusion runs and blistering rock licks are worth checking out for any fan of guitar music.

I got a chance to talk with Herring about getting his start with Bruce Hampton and The Aquarium Rescue Unit, incorporating outside sounds into his playing and why he can’t stand being a bandleader.

GUITAR WORLD: One of my favorite aspects of your playing is your ability to apply jazz harmony into an aggressive blues/rock approach. To me your playing sounds unique when compared to a lot of fusion guitarists in the way you incorporate a real soulful blues feel into your sound. Can you describe how you cultivated that style?

Well, thank you. I was playing with Bruce Hampton, Oteil Burbridge, Jeff Sipe and Matt Mundy in a band (Aquarium Rescue Unit) years ago, and I was really into bands like The Dixie Dregs, Mahavishnu Orchestra and Allan Holdsworth. I couldn’t play like those players, but that’s what I wanted to do and that’s the music I was into at that particular time.

But Bruce, being the bandleader, was really into to deep blues. And so I got a huge lesson in deep blues. Sure, I’d heard Jeff Beck and Stevie Ray Vaughan and was really into all that stuff and loved how they played, but Bruce went way further back. We were listening to Son House, Albert King, Freddie King, B.B. King, Bobby Bland and all that stuff. Hubert Sumlin was huge; his style just blows me away when I hear those old records. And though I already loved blues, I guess being with that bunch of guys, that style just stuck. The music we played was really simple and that gave us a chance to try new things because we weren’t playing songs with a lot of chord changes.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Soon we started to discover the half-step-whole-step diminished scale, and we started messing with that as a group. I knew what that scale was, but I never really used it because there weren’t really chord progressions in the music I was playing that called for it. So when I heard Oteil start to use it a little bit, I was like, “Wow.” And then we started researching some of the chordal possibilities with that scale. Before I knew it, we could be playing blues and sounding really “in,” and then I could go into that diminished scale and Oteil, our bass player, would immediately start playing chords that fit that scale. So my style was able to go that way because of who I was playing with.

I know for a lot of guitar players, myself included, it can be difficult to make that whole-step-half-step scale sound natural during a solo. Can you go into more detail about how you are able to utilize the diminished scale in your playing without it sounding forced?

Well, I think it has to do with the fact that if you take a half step-whole step diminished scale (1, flat 2, flat 3, 3, sharp 4, 5, 6, flat 7) and then remove certain notes (flat 2, 3, 6,) there’s almost a blues scale in there (1, flat 3, sharp 4, 5, flat 7). I’ve been messing with that for years and that’s probably how it’s able to sound semi-natural. I wrote the tune “Scapegoat Blues” for an album I did a few years ago, and the idea was to mix the blues with that tonality. That’s when I discovered, “Wow, it’s already in there.”

There are other things too. You can break up that scale into fragments and pieces and get a lot of mileage out of it. One way would be if you took a dominant seventh arpeggio and you put in a sharped 4, (1, 3, sharped 4, 5, and flat 7). So that is a fragment from the diminished scale and it’s also got blues scale notes in it. It can also be thought of as a modified mixolydian thing, a mixolydian scale with a sharp 4 (1, 2, 3, sharp 4, 5, 6, flat 7), which is a really a melodic minor mode. Coltrane was really into doing things in diminished motion. For example, if you have a pentatonic idea you can move it up a minor third, and then move it up another minor third and then another, and then after that if you move it up again you’re just up an octave from where you started. He was an absolute master of that tonality and a good place to look to for inspiration.

Another pattern-based approach I hear a lot in your playing is the rolling repeated triplet patterns you move up and down the neck. Can you describe this technique?

Well, I loved guitarists who could play legato lines really well, so naturally that led to me Allan Holdsworth. His thing is just indescribable. He’s on a whole other level, one of my favorites on any instrument. Trying to emulate him in a very limited fashion is where that must have come from. It’s basically just four notes. So say if you’re in a G blues position, you can play the sixth fret on the second string and then pull off down to third fret, and then move to the third string and pull off from the fifth fret to the third fret. To move back up the pattern you play hammer-ons from the third fret to the fifth on the third string, and then the third fret to the sixth fret on the second string, and you can repeat the fragment starting with the pull of again.

But you can also change a note or two and play it another scale. The string grouping doesn’t matter, and you can change the notes to fit any scale or chord. But I’ve actually been trying to stop doing it because I’ve been doing it too much. A little bit goes a long way and I guess sometimes I go too far with it. If the tempo is fast, then it’s cool to do it in triplets, but I’ve found a lot of ways to add another note into the pattern so it doesn’t sound like straight triplets. We laugh about it all the time. I get called out by some of my friends, they’re like, “You’re doing that again huh?” And I’m like, “Well, I ran out of ideas!”

You’ve toured with a lot of legendary musicians including The Allman Brothers Band, The Dead and Lenny White, as well as with Bruce Hampton and The Aquarium Rescue Unit and now with Widespread Panic. Can you describe what it’s been like to find your role in all these different groups?

You have to kind of throw yourself into it. That’s another great plus from playing with Bruce; in that band you had to be ready for anything. There weren’t complicated arrangements, but the idea was for you to keep the music super simple and then when you’d improvise you could do anything. I was playing with people who were going to listen to you and react to what you were playing, and you were expected to do the same whenever someone else was soloing. It was a great lesson and it kind of prepared me for playing with all of these different groups.

Then Jazz is Dead happened and it forced me to play things out of my comfort zone, namely learning a bunch of Dead tunes. Soon after I started playing with The Allman Brothers and Phil Lesh. I was an Allman Brothers fan as kid, and though I had never really played that music, it was in my subconscious. The Grateful Dead was too, but not quite on the same level. You just kind of do what you have to do. It’s a scary thing to get a call from someone and feel like, “Oh man, I’m not ready,” but my method is to listen to the music a lot before I even try to play it. I try to get the music in my head before I make the transition to being in the band.

With Widespread Panic, I had known these guys for 20 years before they called about playing, so it helped that they were they were my friends and that I didn’t feel the same kind of pressure as with The Allman Brothers or The Dead. Each of these bands has a different language that they speak, and it’s helpful if you take a little time to listen to the music beforehand so you’re not trying to learn the music the first time you’re hearing it.

Is touring with the Jimmy Herring Band as bandleader a very different experience?

Oh, god yes. It’s really different and not something I’ve ever really wanted to do. With the first band I had when I was young, I realized if it’s your band and you’re trying to be the leader and the other guys in the band don’t dig it then you can look like a real jerk. So I did that and then I realized that I just want to be a sideman. I’d rather just be responsible for my own adequacy. If I show up to the gig and someone doesn’t know the song then it’s not my concern and I don’t have to be the one to yell at him. So for my entire music life, I didn’t do it again, until about three years ago. I didn’t even really do it then; I just wanted to get together with my friends and play some music. There wasn’t that much band leading involved. The guys I picked to play with I’d known forever so it was easy to tour with them. But being the bandleader means being the first one to get the call if something goes wrong and that’s tough.

The Jimmy Herring Band is featured on The New Universe Music Festival DVD/CD along with a number of fusion legends. What was playing that show like?

That was a lot of fun, but it was also nerve-racking to have these masters hanging around. But they were all so cool. Wayne Krantz, John McLaughlin and Alex Machaceck were all there along with so many other great musicians. It was incredible.

I got the chance to see you play at The Comes A Time Tribute to Jerry Garcia at the Greek Theater in Berkeley in 2005 with a bunch of great musicians including Warren Haynes, Trey Anastasio and members of The Grateful Dead. Do you remember anything about that show?

Oh, yeah, absolutely. That was fun. I got to play with Trey, whom I hadn’t played with in a while. The Aquarium Rescue Unit and Phish used to play together quite a bit back in the old days. We were coming up at the same time and you knew those guys were going to be huge. They were really cool to us. We would go up to the Northeast and open for Phish and then they would come down south and open for us in places like Atlanta and Tuscaloosa. And we would be laughing like, “Phish is opening for us, what a joke!” because we knew they were going to take over the world. You could see it coming and eventually they did. But yeah that was a really fun night.