Interview: Roger Waters, David Gilmour Discuss Making 'The Wall' in 2000 Guitar World Interview

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Thirty-two years ago, Pink Floyd built The Wall, an achievement that is still being celebrated today. In the following comprehensive history, Guitar World chronicles the making of rock’s grandest concept album, and how it nearly destroyed its creators.

This story originally appeared in the March 2000 issue of Guitar World.

“I actually still have the drawing at home,” says Roger Waters, recalling the first of countless sketches he made for Pink Floyd’s opus, The Wall. The idea came to Waters in 1977. “Sitting on a plane or in a bar somewhere,” he remembers, “I got a piece of paper and drew a picture of this wall [running] across an arena, with a stage. When I did that I got very excited; I thought, Wow, what a great piece of theater it would be to do that — actually to construct a wall between the band and audience during a concert.”

Waters’ concept turned out to be much more than an interesting piece of rock theater. Since its release, The Wall has sold over 40 million units, making it the third biggest-selling album of all time. It spawned one of the largest, most elaborate stage productions ever mounted in rock—so large, in fact, that the show could only run for a handful of performances in four cities and all but bankrupted the band in the process.

WHAT SHALL WE DO NOW?

Like most musical monuments, The Wall was not built overnight. By the late Seventies, Pink Floyd had been through more than a decade’s worth of trials and triumphs and were on the verge of collapse from within. One of Britain’s first psychedelic bands, they’d arisen out of the mid-Sixties Swinging London scene and had managed to survive the descent into madness and subsequent departure of their original leader, the brilliant guitarist, singer and songwriter Syd Barrett.

The void Barrett left was partly filled in 1968 by David Gilmour, who was to prove one of the most distinctive guitar stylists of the rock era. Joining forces with founding Pink Floyd members Roger Waters (bass/vocals), Rick Wright (keyboards) and Nick Mason (drums), Gilmour helped launch Pink Floyd’s second incarnation. With albums like Dark Side of the Moon (1973), Wish You Were Here (1975) and Animals (1977), the four men established themselves as the Seventies’ premier space-rock band, noted for their cosmic extended instrumental jams, evocative sonic textures and increasingly elaborate stage shows.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Over the years, however, the band became less of a jam-based collective and more of a vehicle for Waters, who had come into his own as Pink Floyd’s major thinker. Waters’ ideas had played a leading role in shaping Dark Side, Wish and Animals into multidimensional concept albums and in making opulent spectacles of Pink Floyd’s live concerts, which featured increasingly elaborate stage props, such as the infamous 40-foot inflatable pig devised for the Animals tour.

But Waters’ ascendancy had created no small amount of bad feeling between himself and his bandmates, who tended to view the bassist as an increasingly tyrannical control freak. Friction between Waters and Gilmour grew particularly intense, as both men vied, in very different ways, to fill Syd Barrett’s shoes—Gilmour through guitaristic prowess and melodic songcraft, and Waters through boldly experimental concepts.

Born in a psychological war zone, The Wall strained Pink Floyd to the breaking point. It proved to be the last Pink Floyd album recorded by the full Waters/Gilmour/Wright/Mason lineup and Waters’ penultimate project with the group.

“There’s always been tension,” Gilmour says of his relationship with Waters. “But it was all quite controllable until after the Wall album. There’s such a thing as creative tension. And then there’s total egocentric, megalomaniac tension, if you like.”

IS THERE ANYBODY OUT THERE?

There were other tensions in the air at the time of The Wall’s creation — tensions within rock music itself. By the late Seventies, the punk rock revolution had heaped much invective on the decade’s big stadium-rock bands such as Pink Floyd. Punk moved rock music back into small clubs, which permitted a closer connection between bands and their audiences. Punk ideologues honed in on Pink Floyd’s inflatable pig prop, in particular, as a symbol of the bloated, foolish thing corporate rock had become.

What few punk rockers realized at the time is that Roger Waters had come to the exact same conclusion himself. As Pink Floyd had moved from small psychedelic venues like London’s UFO club into larger and larger arenas and stadiums, Waters had come to feel increasingly alienated and isolated from concert audiences.

“It was magical in the early days of Floyd,” he says. “But the magic was eaten by the numbers. Until, by ’77, when we were doing the Animals tour—playing only big stadiums and selling out everywhere — all everyone was talking about was grosses and numbers and how many people there were in the house. And you could hardly hear yourself think. You could hardly hear anything [onstage] because there were so many drunk people in the stadium, all shouting and screaming.”

The situation reached a crisis point during a Pink Floyd concert at Olympic Stadium in Montreal, where Waters spat at an especially obnoxious fan. Appalled by his own behavior, the bassist began to ponder how things had ever come to such a pass that he could feel actual hostility toward a member of his audience. Shortly after the Montreal incident, Waters came up with the aforementioned drawing of a gigantic wall, a barrier between performers and spectators.

The incredible power of the image Waters chose lies in its simplicity and universality. It is an ancient, quasi-mystical symbol that comes down to us from the dark recesses of Biblical and classical antiquity. Writers from Melville to Sartre have used the wall image as a symbol of alienation. It has become particularly identified with the feeling of existentialist isolation unique to the post-WWII era — the latter half of the 20th century. In this epoch, we all live behind walls— political, psychological, social, self-imposed or otherwise. In applying this rich motif to rock—the great, late 20th century populist art form— Waters found the basis for the most ambitious project of his career. In the past, he’d played an important role in creating concept albums for Pink Floyd. But now he envisioned a concept album that would also form the basis for a series of concert performances and a feature film.

“I needed to construct the whole piece,” Waters says. “So I started thinking, Well, what is this wall, and what’s it made from? Then the idea started to occur to me that the individual bricks might be from different aspects of the history of my life and other people’s lives. And I started to fit things together.”

Back at his country home, Waters began writing songs for what would become The Wall. He put together a demo tape “that was only 43 minutes long, or something like that,” he recalls. During the same period he worked up a rough demo for another project, The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking, which would eventually become his first solo album.

Initially, however, both projects were presented to the other members of Pink Floyd. Waters invited them to choose which of the two demos they wanted to make into the next Pink Floyd album. They opted, of course, to do The Wall.

At this juncture, the band was on the brink of bankruptcy, owing to some ill-advised business investments. They desperately needed another best-selling Pink Floyd album, on the order of Dark Side of the Moon or Animals. It has been widely speculated that Pink Floyd might not have stayed together to make The Wall had they not been in such dire financial straits. The situation being what it was, Gilmour, Wright and Mason joined forces with Waters to make what would become a fittingly grand last hurrah for Seventies rock, and a record that would set the stage for Waters and the other group members to go their separate ways in the Eighties. It was deemed necessary, however, to bring in an outside producer— rock vet Bob Ezrin—to work on The Wall. Ezrin’s role, in part, was to act as a mediator, particularly between Waters and Gilmour.

“It was, for the most part, a typically British polite enmity that existed between them,” Ezrin recollects. “They were obviously close on many levels. And there was an unadmitted mutual respect beneath all the arguing and bickering going on between them. But the tension was always present because there was a war between two basically dominant personalities. Each one had a need to express himself in his own style. And sometimes these styles were very different. Sometimes they approached the same piece of material from an entirely different point of view. So my job was often to be Henry Kissinger and run back and forth between the two of them, trying to arrive at a workable middle ground.”

EMPTY SPACES

Perhaps best known, at the time, for his production work with Alice Cooper and Kiss, Ezrin had also produced Peter Gabriel’s first solo album (a particular favorite of Waters’) and had helped bring Lou Reed’s bleak, difficult concept album Berlin into being. Before sessions for The Wall began, Ezrin spent some time with Waters, massaging the plot line. “I went and spent a weekend with him and reviewed his original demo,” says the producer. “In there were the germs for I’d say half the songs that ended up appearing on the final album. From that, we refined the plot line and developed a slightly different story from the original one that Roger had. We filled in holes, the way you do with a movie script, and built the album around the story.”

One of Ezrin’s suggestions was to change The Wall from a first-person narrative in Waters’ own voice to a third-person story focusing on a character named Pink Floyd. (This name comes from a long-standing joke about the band’s early days, when they’d turn up at gigs and be asked by club management, “Okay, which one of you is Pink, then?”) Pink’s father, an RAF fighter pilot, dies in WWII when the boy is still in infancy. In the piece, war functions as a metaphor for what corporate rock had, in Waters’ view, become. Touring rock bands are like soldiers wearily slogging from one town to the next, “doing their duty” for their corporate superior officers back at record company HQ. The indignities suffered by stadium rock concertgoers—festival-seating stampedes, deafening P.A. systems—are likened to the sufferings visited on victims of war. All this might seem a bit of an over-exaggeration. Or perhaps not, depending on how many stadium rock concerts one has attended.

As the plot unfolds, we see that smothering, overprotective love from Pink’s mother impedes the boy’s psychological development. He begins to erect a mental barrier—a wall—between himself and the outside world. As he grows to manhood, he is further traumatized by a sadistic schoolmaster (emblematic of the repressive British public school system) and the infidelity of his wife. Each of these bad experiences is “another brick in the wall,” causing Pink to withdraw ever further into himself. All of this, however, doesn’t prevent Pink from becoming a rock star, although his rise to fame is not depicted in the story—a curious narrative omission.

By midpoint in the piece (the end of the first disc), Pink has become totally alienated from the outside world. The wall he’d begun erecting in childhood is now complete. Isolated in a solipsistic inner world, he becomes prey to “the worms”: his own anxieties, doubts and fears. After receiving an injection to rouse him from his catatonic state so he can perform onstage (the subject matter of “Comfortably Numb”), a strange transformation comes over Pink. He turns into a quasi-Nazi. His concert performance that evening takes the form of a fascist rally, with Pink singling out “queers,” Jews and “coons” in the audience, singing “If I had my way, I’d have you all shot” (“In the Flesh”).

With this rather strong metaphor, which some have found in questionable taste, Waters is dramatizing the feelings that led him to spit on the audience member at the ’77 Montreal show. But if Pink is hard on his fans, he’s even harder on himself. The final scenes of The Wall take the form of a trial enacted within Pink’s own psyche. A “worm judge” presides. The sadistic schoolmaster and faithless wife return as witnesses who testify against Pink. The verdict is to tear down the wall Pink has built around himself. But the ending is ambiguous. Is the wall’s collapse a good thing—a return to reality for the troubled Pink? Or is it a bad thing—a further trauma for the already unbalanced protagonist?

The final lines of the piece sound a note of sympathy for those close to Pink. (The same ones who drove him crazy in the first place?) For them, “it’s not always easy banging your heart against some mad bugger’s wall” (“Outside the Wall”).

As far as plot is concerned, it’s hard not to notice The Wall’s many similarities to an earlier rock opus, the Who’s Tommy (1969), which also formed the basis for a double album, a rock concert performance, a film and—years later—a stage play. Tommy, like Pink, has a British fighter pilot for a father, and as Tommy opens, we learn that the protagonist’s father is missing in action, presumed dead, in the war (WWI in the album version, WWII in the film). Also like Pink, Tommy withdraws into himself as a result of psychological pressures brought to bear by his mother. Pink becomes a rock star. Tommy becomes a messianic guru, not unlike a rock star. Tommy and Pink both turn authoritarian on their followers toward the end of their respective stories. Pink undergoes an awakening of sorts when a wall is torn down. Tommy undergoes a similar jolt to consciousness when a mirror is smashed.

Waters’ plot gets few points, if any, for originality. But what sets The Wall apart from Tommy is its tone. Tommy is much lighter in mood, reflecting the spiritual aspirations of its author, Pete Townshend, as much as his doubts about rock stardom. Pink’s alienated psyche is a hellish, worm-infested place. Tommy’s isolation is “a quiet vibration land,” a quasi-meditative state of peace and stillness. The villains in Tommy— Cousin Kevin, Uncle Ernie, etc.—are presented with a note of broad, albeit dark, comedy. But there’s nothing funny about Pink’s tormentors. They have the cruel stench of real human beings.

It’s no secret that Waters was profoundly influenced by the raw, painfully confessional approach that John Lennon had pursued on his first solo album, Plastic Ono Band (1971). Much like Lennon, Waters was traumatized by the early death of a parent. And unlike Pete Townshend, Waters’ father really did die in the Second World War.

“When I was three or four,” Waters recalls, “suddenly there were these men in uniform picking the other kids up from kindergarten. My father was missing in action. So there was always that feeling of ‘maybe one day…’ You know? I’ve written lots of poetry about that, apart from all this stuff in The Wall. I think that is maybe one of the things that makes people performers. I think it engenders in you a tendency to jump through hoops. ‘Maybe if I jump through this hoop, my dad will come back.’ I know it sounds crazy. But I really think that.

“A few years ago I had a kind of enlightening moment in my therapeutic process: I suddenly was able to explain dreams that I had had periodically throughout my life. I used to have this very vivid, recurring dream that I’d murdered somebody and I was going to get caught, get punished, whatever. And I came to the realization that, on some subconscious level, I felt that I had killed my father. I was born and he died. I haven’t had the dream ever since that realization. So I don’t know—maybe that whole experience has provided me with part of whatever it is one needs to empathize. That’s partly why a lot of my work focuses on the impotence of the innocent victim.”

It is this aspect of The Wall that speaks most urgently to the post-grunge generation of rock fans. Korn, for instance, hit a tremendously responsive chord in its young audience by dealing with the early life psychological traumas and purported childhood abuse of band leader Jonathan Davis. The image of a child’s battered cuddly toy used in the cover art for Korn’s latest album, Issues, bears an uncanny resemblance to a similar image that graphic artist Gerald Scarfe created 20 years earlier for The Wall’s album jacket and motion picture animation.

Consciously or not, Marilyn Manson also seems to borrow heavily from The Wall on his Antichrist Superstar album. A “worm” motif figures prominently in that work. And its protagonist also develops a Nazi alter ego, just like Pink. In fact, the album’s cover photo of Antichrist Superstar in Nazi-style regalia is strikingly similar to the costume, makeup and hairstyle used by Bob Geldof during the “fascist rally” scenes in the film version of The Wall.

BRING THE BOYS BACK HOME

Around April 1979, members of Pink Floyd did a little recording for The Wall at their own studio, Britannia Row, in England. But after a few sessions they were informed by management that, owing to tax issues stemming from their recent financial difficulties, they would have to make the album outside of England. So the quartet moved operations to Superbear studios in France and then completed the album at Producers Workshop in Los Angeles. The album was still only partially written when sessions got underway.

“Some things were kind of complete on the original demo,” Waters recalls, “including ‘Waiting for the Worms,’ ‘Mother,’ ‘Another Brick in the Wall,’ parts 1, 2 and 3 and ‘Is There Anybody out There.’ A lot of the stuff obviously developed after that. I remember sitting in a room while the tracks were being recorded and writing ‘In the Flesh,’ ‘Nobody Home’ and ‘Comfortably Numb.’ ”

The latter song, one of the best-known and -loved pieces from The Wall, marks one of David Gilmour’s few songwriting collaborations with Waters on the album. (He also co-wrote “Run Like Hell” and “Young Lust.”)

“Bob Ezrin’s desire was to make The Wall a Pink Floyd record rather than Roger’s solo record,” Gilmour recalls. “Roger wanted it to be all his solo project; he didn’t want anyone else to contribute to the writing. But Bob thought there should be other people’s writing on the album. So he said to me, ‘What have you got?’ And I played him my demo for ‘Run Like Hell’ and what became ‘Comfortably Numb.’ Bob said, ‘Oh, they’re really nice. We should include them.’ Roger said, ‘Well…alright.’ It was a long hard process making that record: throwing bits away, tough editing, going to meetings…”

A brilliant evocation of the narcotized, desensitized, late-20th century consumerist malaise we all live in, “Comfortably Numb” combines the best of Waters’ lyrical incisiveness with some of Gilmour’s finest music. It is one of several songs on The Wall to employ a lush orchestral arrangement, written by Ezrin and composer Michael Kamen, which further enhances Gilmour’s musical themes. Though few in number, Gilmour’s songwriting contributions to The Wall impart a welcome element of melodicism.

They contrast effectively with Waters’ own compositions, many of which are sung in a style that Waters developed especially to portray the character Pink—a crabbed, stagily strident set of vocal mannerisms a bit reminiscent of the Kurt Weill/Bertolt Brecht operas of 1920s Berlin. When “Comfortably Numb” comes along, midway through The Wall’s second disc, its effect is not unlike that of an operatic aria—a burst of sublime melody that momentarily lifts the listener out of the creaking mechanics of plot development. The chord progression and some melodic elements for “Comfortably Numb” came from a song idea that Gilmour had developed for his first solo album, David Gilmour (1978), the guitarist discloses:

“I’d recorded a demo of it when I was at Superbear studios previously, doing my first solo album. We changed the key of the opening section from E to B, I think. Then we had to add a couple of extra bars so Roger could do the line, ‘I have become comfortably numb.’ But other than that, it was very simple to write. And it was all done before the orchestration was added. But there were arguments about how it should be mixed and which backing track should be used. I think it was more of an ego thing than anything else. We actually went head to head over which of two different drum tracks to use. If you put them both on a record today, I don’t think anyone could tell the difference. But it seemed important at the time. So it ended up with us taking a drum fill out of the one version and putting it into the other version by editing a 16-track tape—splitting it down the middle so you have two strips of tape, one-inch wide.” [This is called a ‘window edit’—Ed.]

Tempers flared during the mixdown of “Comfortably Numb” in Los Angeles. A particularly heated confrontation between Gilmour and Waters took place over dinner one night at an Italian restaurant in North Hollywood. “There was no screaming, though,” says Ezrin. “It was all very English, very direct: ‘You’re a fuck and you have no reason to live.’ That sort of cold, head-on English confrontation. And I was right in the middle of it. I was fighting at that point for the introduction of the orchestra and the expansion of the Pink Floyd sound into something that was more theatrical, more filmic. But Dave really saw ‘Comfortably Numb’ more as a bare bones track with just bass, drums and guitar. Roger sided with me on that particular point. What we ended up with is the body of the song being more heavily orchestral, and then the end clears out somewhat and is more rock and roll. So ‘Comfortably Numb’ is a true collaboration because it’s David’s music, Roger’s lyrics and my orchestral chart!”

Gilmour contributed an especially expressive guitar solo on “Comfortably Numb.” Although it is beautifully structured, the guitarist says very little forethought, if any, went into it: “As far as I remember, I just went out into the studio at Superbear, bunged five or six solos down and then just picked the best bits from each one.”

Other aspects of the project weren’t so random. Given their financial predicament, Pink Floyd badly needed a hit single. The group had never really released singles or catered to that market and were reluctant to do so now. But Bob Ezrin heard considerable melodic potential in “Another Brick in the Wall,” a Waters composition that is restated at three different points in the narrative, each time with a different musical arrangement and different lyrics.

“Another Brick in the Wall (Part 2)” contained the memorable lines, “We don’t need no education, we don’t need no thought control,” but didn’t have enough verses to conform to the conventional pop single format. Ezrin had had great success using a children’s chorus on Alice Cooper’s “School’s Out,” a song similar in subject matter to “Another Brick in the Wall (Part 2).” So word was sent back to Pink Floyd’s Britannia Row studios in England. Engineer Nick Griffiths arranged for some children from Islington Green School, just around the corner from Britannia Row, to come into the studio. Griffiths set up some mikes and the children, under the direction of their music teacher, sang the lyric to “Another Brick in the Wall (Part 2),” imparting particular gusto to the line, “Hey, teacher, leave us kids alone!”

“We were at Producers Workshop at the time,” Waters recalls. “I remember sending the multi-track tape to Nick Griffiths in London and asking him to copy the backing track, record the kids, stick it all together and send it back to us. We just had one conversation. The tape came back in a Federal Express parcel, and I remember saying, ‘Oh let’s have a listen.’

“I feel shivery now remembering the feeling of what it was like hearing those kids singing that song. I knew it was a hit record. There were a lot of great moments like that, when we were working at Producers Workshop.”

On a less cheerful note, Rick Wright, who’d been with Pink Floyd since the beginning, was dismissed by Waters during the making of The Wall. Waters felt the keyboardist wasn’t pulling his weight. Bad feelings first arose over Wright’s wish to be a producer of the album, along with Waters, Gilmour and Ezrin.

“We agreed at the beginning that if Rick really did help with the production he could then call himself a producer and get credit for it,” says Waters. “So Rick would sit in on the sessions from morning until night every day and never left the studio. At a certain point, I remember Ezrin getting irritated because Rick said he didn’t like some idea. And I remember Ezrin saying about Rick, ‘Why does he sit here all day?’ I said, ‘Don’t you understand? He thinks he’s producing the record.’ Ezrin said, ‘Don’t be ridiculous.’ To which I replied, ‘I promise you. You ask Rick. But wait ’til I’m not here!’ He asked him and came back and said, ‘You’re absolutely right. That’s exactly what he thought.’ So I said, ‘Have you told him?’ And he said, ‘Yeah. I told him that’s not what producing a record is.’ So we never saw Rick again. That was it. He disappeared.”

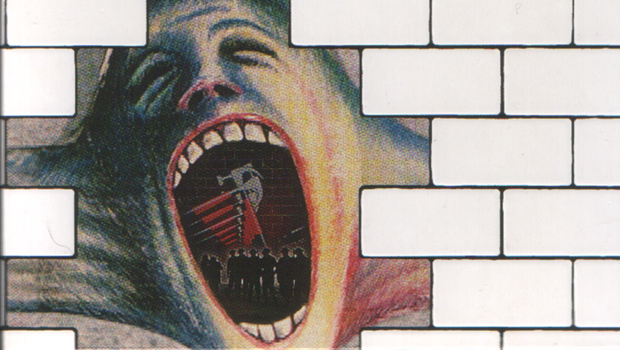

Waters also fell out with graphic designer Storm Thorgerson, who’d been creating Pink Floyd album covers and other artwork for years. Satirical cartoonist Gerald Scarfe wound up collaborating with Waters on the sleeve design for The Wall. Scarfe’s artwork would become an integral part of the live concert presentation of The Wall and the subsequent film as well.

Released on November 20, 1979, the Wall album was an instant commercial success. But Waters and the surviving members of Pink Floyd had scant leisure to savor their triumph. They plunged almost immediately into the next phase of the project.

IN THE FLESH

The Wall had initially been conceived as a live performance statement. Before he’d written a note of music or a single scrap of plot, Waters had become obsessed with the powerful visual image of a huge wall stretching across the proscenium of an arena stage. In transforming Pink Floyd’s concept double album into a concert spectacle, Waters finally got to build his wall—or rather a full crew of stage hands did, brick by massive cardboard brick, on a nightly basis. The gigantic 130-feet-wide by 65-feet-high edifice was raised at the lip of the stage as Pink Floyd played the album’s music. By the time the colossal edifice was completed, midway through the show, Pink Floyd were completely obscured from the audience’s view, hidden behind the wall—an epic-scale enactment of Pink’s, and by extension Waters’, moment of greatest alienation.

During the second half of the show, the big cardboard wall became the single biggest prop in the entire history of rock and roll. Brick faces swung open to disclose sets and scenes: Pink (played by Waters) in his hotel room. Gerald Scarfe’s nightmarish animations were projected onto the wall. David Gilmour stood on top of the wall, like the conquering hero in a Hercules movie, to play the “Comfortably Numb” solo. And in the end, of course, the wall came tumbling down, like its Biblical predecessor in Jericho.

Everything about the production was big. There was even a surrogate band: guitarist Snowy White, bassist Andy Bown, drummer Willie Wilson and keyboardist Peter Wood. Intended to represent Pink’s band when the protagonist has entered his psychotic fascist alter ego, this quartet came onstage before the actual members of Pink Floyd to play the opening number “In the Flesh,” wearing masks of the four Pink Floyd members’ faces. White, Bown, Wilson and Wood then acted as auxiliary musicians throughout the rest of the show. Bown’s presence freed Waters from the bass, so he could act out scenes in character, as Pink—albeit with a big pair of headphones on. (This was before the invention of in-ear monitors.) At the time, Waters also groused that Wilson and Wood were necessary because Nick Mason and Rick Wright couldn’t play well enough. Although Wright was officially out of Pink Floyd at this point, and had been excluded from the band’s business partnership, he did play the Wall tour on a salaried basis. Consequently he is the only one of the four who made any money off the tour. The other three sunk their own funds into the enormous production.

And truly enormous it was: 45 tons of equipment and a 45,000 watt P.A. It was quickly determined that many venues just couldn’t accommodate so big a show. For a few mad, Spinal Tap moments, the band considered designing and building their own portable concert venue—a kind of high-tech circus tent shaped like a giant slug.

Ultimately, however, the “slug” idea was abandoned. Realizing that the show was too big to be a conventional rock tour, Pink Floyd decided to do extended runs at venues in four major cities: the Los Angeles Sports Arena, Nassau Coliseum just outside New York, Earl’s Court in London and Westfallenhalle and Dortmund, West Germany. While all these venues are large arenas, none are the huge sports stadiums that Waters so hated playing, a hatred that moved him to write the wall in the first place.

The scope of the show enabled Waters to include a number of songs he had written for The Wall but which didn’t make it onto the album. The job of coordinating the live music with all the elaborate staging elements fell to David Gilmour, who was appointed musical director for the show.

“For me the Wall show was terrific fun,” says the guitarist. “Really an achievement for everyone involved, particularly Roger. But I had to take on the role of music director and deal with a lot of musical details onstage so that Roger didn’t have to think about that. It was really tough at first. Later on it got a little easier, once we all got into it. But I had a huge cue sheet up on my amps, because we had all these cues coming up on monitors or on screen, and there were different DDL settings which I had to transmit with very primitive equipment to all the delay lines onstage. Very tricky. Except for the ‘Comfortably Numb’ solo, there were virtually no moments where I could say, ‘Forget everything. Just play.’ You know?

“It was very rigid. On all the previous tours— Wish You Were Here, Dark Side of the Moon— there were moments that could be extended longer or made shorter if you liked. The Wall, quite reasonably, because it was a different kind of project, didn’t have that.”

After a rehearsal in nearby Culver City, the show opened in Los Angeles on February 7, 1980. As if the spectacular effects planned by the show’s organizers weren’t enough, the opening night audience got a little bonus excitement— a fire onstage early in the performance.

“Andy Bown and Snowy and those guys did their thing,” Waters recalls, “And then this drape went up to reveal us. Fireworks had gone off beforehand and one of the Roman candles had gotten into this drape and set light to it. I was singing away and I kept hearing this noise and I thought, God, the P.A.’s going off. ’Cause I could hear this strange noise. Eventually I looked up and saw one of the riggers, a guy called Rocky, leap about six feet through the air, with no safety harness or anything on him, from one drape to another. He had a fire extinguisher in one hand and he was trying to put the thing out. And then lumps of burning drape the size of tennis balls started hitting the stage all around us. And the auditorium was beginning to fill up with smoke.

"I made a decision that this was not cool. So I stopped singing and just shouted ‘stop!’ through the P.A. Throughout rehearsals, the guys out at the mixing console were so used to me constantly yelling ‘stop’—if something wasn’t right, you know. So when I did it during the actual show they must have all thought they were hallucinating. ’Cause they just carried on. So I shouted ‘stop!’ again. This time, they said, ‘Okay, he really does seem to be saying stop. I guess we have to.’ And I said, ‘Look, we’re going to have to lower this drape, because we’ve got a fire. Everything’s cool. We’ll put it out, go back five minutes and pick up from there.’ Which we did. But it was quite a hair-raising beginning to the first show.”

DON’T LEAVE ME NOW

Roger Waters’ working relationship with David Gilmour and Nick Mason lasted through one more album after The Wall: 1983’s The Final Cut. Not long after the making of that record—a difficult process by most accounts—Waters parted company with his two former colleagues on somewhat less than friendly terms. Waters later lost a legal battle in which he sought to prevent Gilmour, Mason and Wright from recording or performing under the name Pink Floyd. It would seem that Waters’ relationship with The Wall is an ongoing one, much like Pete Townshend’s with Tommy. He is currently working on a theater adaptation.

“I’m trying to write some laughs into The Wall,” he says. “Twenty years after having written the thing in the first place, I’m still not sure I understand the ending. But I’ve got a hell of a lot more ideas now then I did in 1979: what happens when you tear down the wall, and what’s out there. I had no fucking idea back then. Maybe what I’ve discovered is that the answer to the question ‘Is there anybody out there?’ is ultimately no. That’s not what’s important. What’s important is what’s inside you. Of course, contact with other people is important. But fundamentally, it’s what’s going on inside that’s most important.”

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.