“Weirdly, I can’t seem to play on 22 frets. It’s this symmetry thing that freaks my mind out, so I need 24”: Meet Jack Gardiner, the Tom Quayle-taught virtuoso turning Baby Shark and Wheels on the Bus into blistering fusion guitar workouts

The Ibanez-toting, Neural DSP aficionado is one seriously gifted player, a bona fide virtuoso who just so happens to do a neat line in nursery rhymes

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

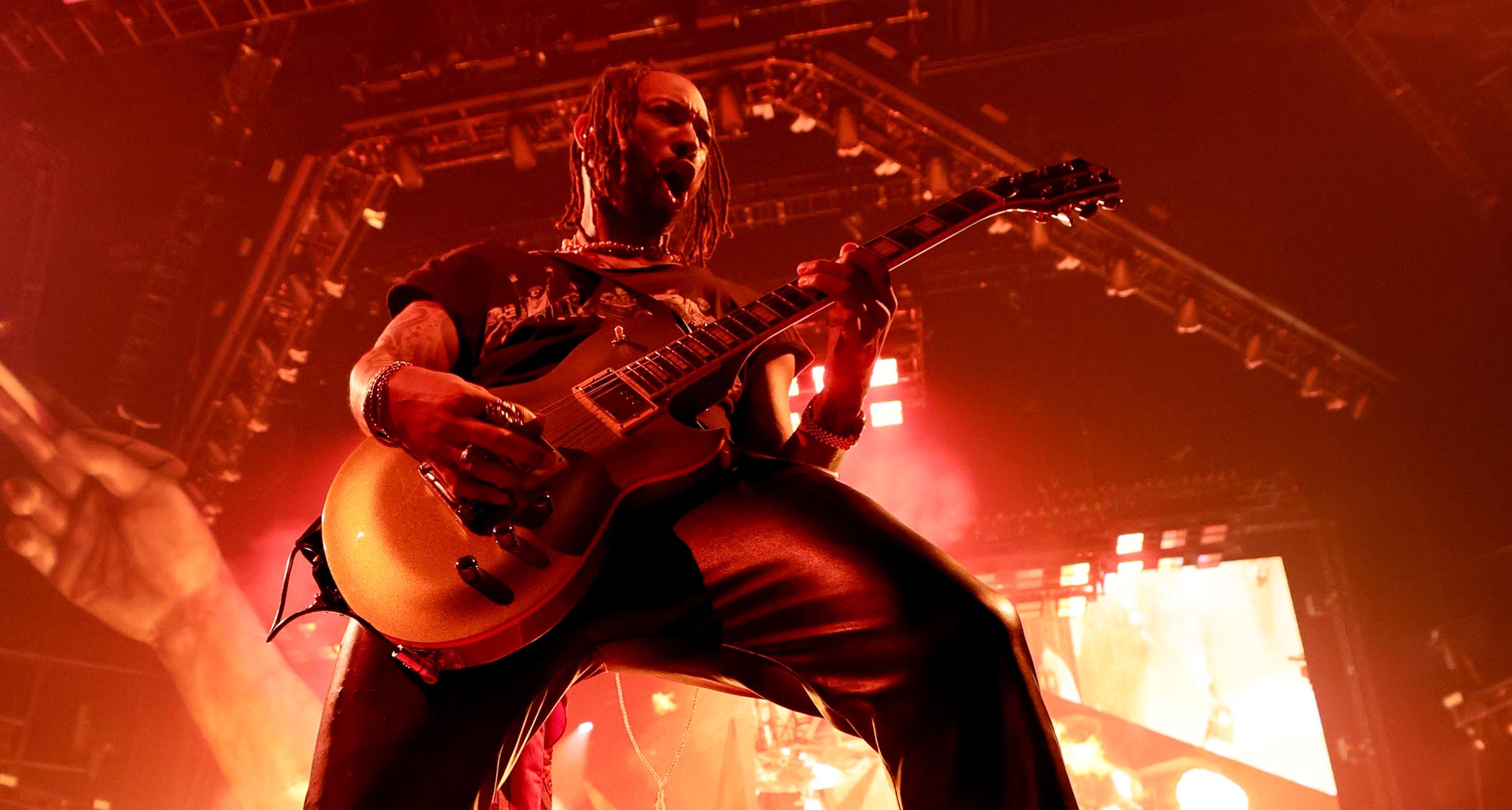

If you’ve been following the Neural DSP channels in recent years, you’ll probably have come across the name Jack Gardiner. The English Ibanez endorsee, who is based in Switzerland, has become one of the rising stars of modern fusion – blending influences from Guthrie Govan, Rick Graham and Tom Quayle into his own unique style.

As it turns out, he was coached by the latter in his mid-teens, and it was Quayle’s guidance that helped him navigate the fretboard and become the player he is today. Not everyone, as Gardiner rightfully points out, gets that kind of support in their formative years.

On the other hand, help will only take you so far. As history has proven time and time again, every musician is ultimately a result of the amount of time and sweat he or she has put into their chosen art form.

In Gardiner’s case, the dedication – from control and theory to technique and phrasing covering just about every style – is crystal clear from the moment you hear him.

What was it like studying with legato mastermind Tom Quayle so early on?

“I had around eight or nine lessons with him. When I was around 16, he’d invite me to come and hang out with him and Rick Graham. Seeing those two play in real life was a big eye-opener for me.

“I’d be sitting there thinking, 'Oh, God, they can actually do that stuff.' I would later reflect on how lucky I was to have been taught by those players. For my style, I would say people like Tom and Rick, as well as Guthrie [Govan], are the masters. It’s like they’ve come from a whole other planet.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Most of my lines come from melodic fusion players like Frank Gambale

What tips can you offer rock players hoping to bridge into fusion?

“Definitely listen to Matteo Mancuso or anyone who fills in the gaps with a lot of chromaticism. You could take an Fmaj7 arpeggio around the eighth fret, for example, and then add notes in – so play something like the eighth, 10th, 11th and 12th frets on the A string, the 10th on the D, and then the ninth and 12th on the G. Then return back to the ninth and play every note up to the 12th that second time.

“I will often follow the exact same thing on the next strings going an octave up, but change the structure of those enclosures. You can apply that concept to any arpeggio. I’ll do it with pentatonic runs. Guthrie and Richie Kotzen use those ideas a lot. You can get away with anything if it’s in between.”

So how far does your theory training stretch?

“The proper outside stuff like Allan Holdsworth still scares me. Players like that think in a different way. When people start talking about the Messiaen modes of limited transposition, my brain turns off. Even with melodic minor, I try to simplify it as much as I can.

“I remember transcribing a Wayne Krantz lick from Whippersnapper, and it took me a second to realize it was whole tone – the stuff I’d been avoiding. Most of my lines come from melodic fusion players like Frank Gambale.”

Weirdly, I can’t seem to play on 22 frets. It’s this symmetry thing that freaks my mind out, so I need 24

You typically play a custom-built Ibanez AZ into a Neural DSP Quad Cortex. Would it be fair to describe your tones as “spanky”?

“Definitely! I started out with a bad Les Paul copy. My first proper guitar was an Ibanez JEM555. I loved it for shred stuff, but it didn’t have the Strat sound. The AZ models are great, being Superstrats with 22 frets.

“Weirdly, I can’t seem to play on 22 frets. It’s this symmetry thing that freaks my mind out, so I need 24. I was begging Ibanez to make me a 24-fret HSS AZ, and apparently it needs a slightly different shape to get that neck pickup close enough to the 24th fret. In the end, they did.”

When did you realize it was time to move from analog to digital?

“I used to be a tube amp guy. I had a Friedman BE-100 at one point, which was my dream amp, though I was mainly using it for ’80s pop gigs with China Crisis. When I moved to Switzerland, I started using Neural DSP and working with them on videos. I got sick of not having the same tones live, and then the Quad Cortex came along.

“Suddenly I could have a compressed Fender funk sound, a Vox chime or even a BE-100. Traveling became the easiest thing, so I’m digital from now on. I’m working on more stuff with Neural, plus new solo material.”

There was one festival we did with A-ha and Seal in front of 40,000 people. Before that, I was doing session stuff for high-end gospel musicians

Your session work stretches from gospel music to playing for China Crisis. What have you learned from those experiences?

“My biggest shows have been with China Crisis. There was one festival we did with A-ha and Seal in front of 40,000 people. Before that, I was doing session stuff for high-end gospel musicians. Tom Quayle noticed that’s when my playing really started to improve, because they’d throw crazy changes into songs like Valerie by Amy Winehouse without explaining what was happening.

“I’d be sitting there at 19 years old, super-innocent, having never heard chords like that. I’d record memos on my phone and work it all out later. Then I realized how it linked into what Eric Gales does, using re-harmonizations that are tasteful and soulful in equal measure.”

Fusion players tend to be quite serious, but we’ve seen you turning songs like The Wheels on the Bus and Baby Shark into re-harmonized jazz odysseys.

“That stuff comes from the Swedish band Dirty Loops. When they formed, they decided to have fun covering songs like Baby by Justin Bieber, precisely because fusion players can get very serious.

“When my daughter became obsessed with nursery rhymes, I tried showing her how to play them on the keyboard, but she lost interest. Hours later, I’d be still playing them, having more fun than I imagined. Honestly, I never thought I’d be talking to Guitar World about The Wheels on the Bus and Baby Shark.”

- See Jack Gardiner for more information on his tuition, music and merch.

Amit has been writing for titles like Total Guitar, MusicRadar and Guitar World for over a decade and counts Richie Kotzen, Guthrie Govan and Jeff Beck among his primary influences as a guitar player. He's worked for magazines like Kerrang!, Metal Hammer, Classic Rock, Prog, Record Collector, Planet Rock, Rhythm and Bass Player, as well as newspapers like Metro and The Independent, interviewing everyone from Ozzy Osbourne and Lemmy to Slash and Jimmy Page, and once even traded solos with a member of Slayer on a track released internationally. As a session guitarist, he's played alongside members of Judas Priest and Uriah Heep in London ensemble Metalworks, as well as handled lead guitars for legends like Glen Matlock (Sex Pistols, The Faces) and Stu Hamm (Steve Vai, Joe Satriani, G3).