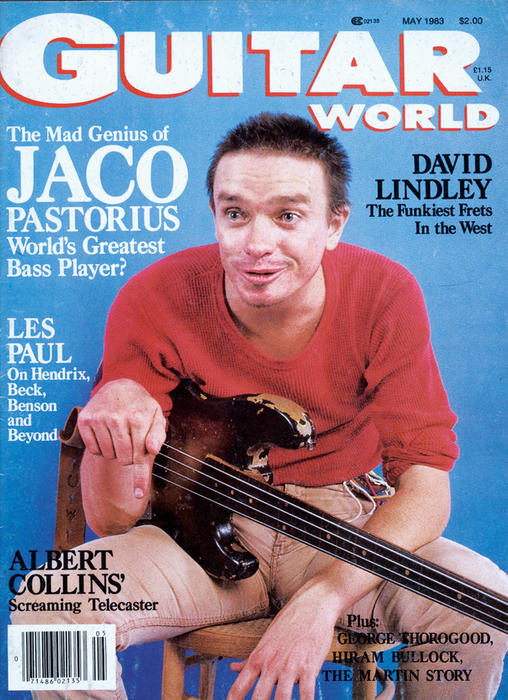

Jaco Pastorius talks Weather Report, playing fast, and why the bass is "the number one instrument in the world" in his first Guitar World interview from 1983

In a freewheeling and candid chat, the late bass legend opens up to GW about improvising, his approach to the four-string and that legendary '62 Jazz Bass

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

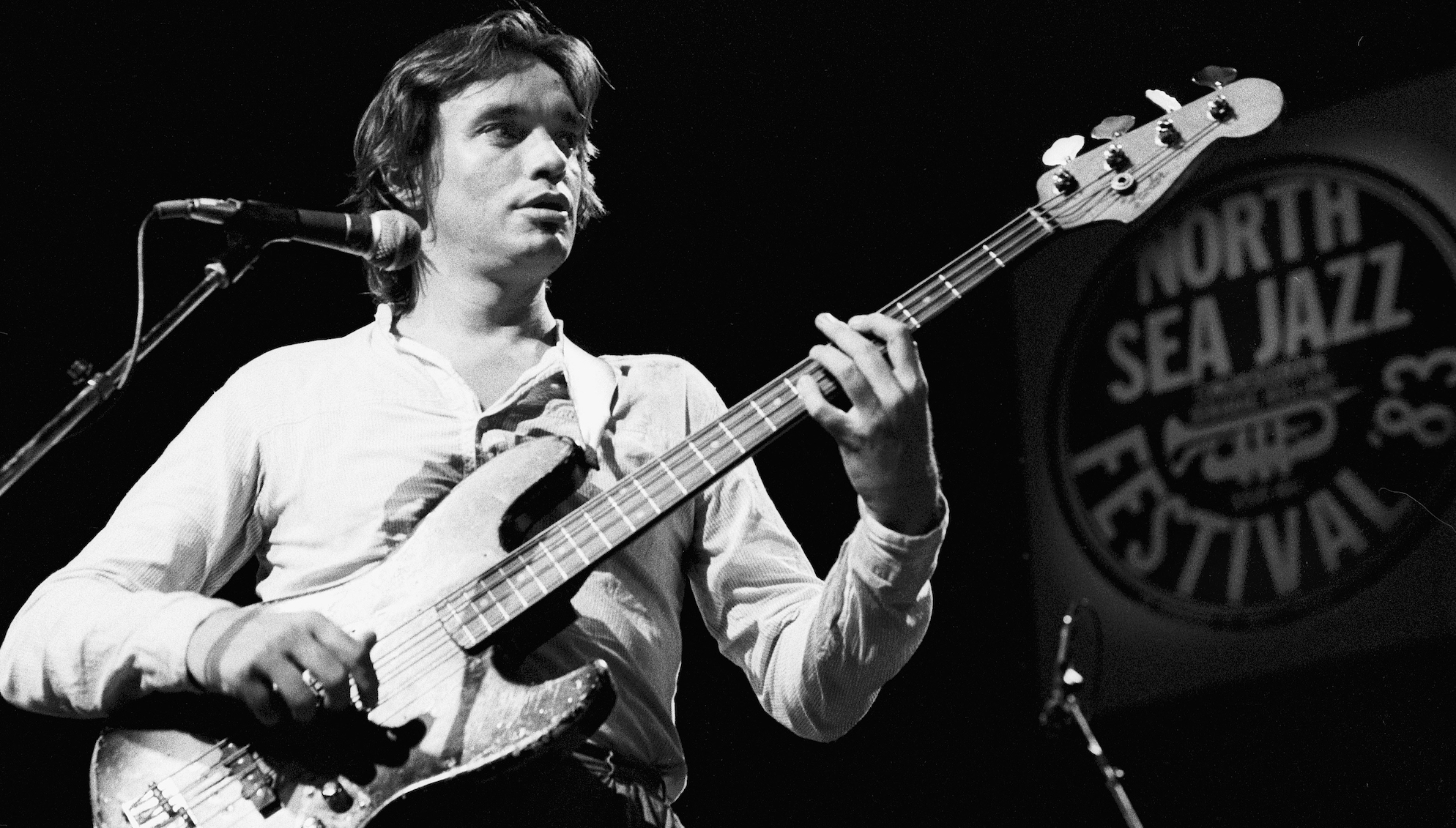

Here's our interview with Jaco Pastorius from the May 1983 issue of Guitar World. The original story by Peter Mengaziol ran with the headline The Wild Man of Bass Comes Clean: A Whacked-Out Interview, and the story started on page 32.

The last thing I expect when interviewing a serious musical visionary is to find a very funny man. After all his pensive poses, the critics' litanies of praise and philosophical reviews, Jaco Pastorius came up to our photographer's studio armed with more one-liners than Henny Youngman.

Nobody was ready for that! It made getting a straight answer kind of tough – because he would follow a profound question with an off-the-wall wisecrack that took ten minutes to register as perfect sense. Often his remarks went over our heads, and other times they hit us at street level.

He also brought along a sidekick, who played the part of straight man: Victor Bailey, Weather Report's new bassist. Theirs was the funniest historical meeting ever.

There was something funny, too, about how we got with Jaco. A series of late-night phone calls from Florida to the Guitar World offices. An invitation to the famous electric bassist to fly to New York. Jaco hemming, hawing, hesitating, resisting. Ten minutes later a return call: "I'm on the next plane." The next day, GW staffers picked him up at a Soho jazz bar.

Jaco walked into Jonathan Postal's studio with his famous Fender Jazz bass slung on a strap. He led Victor into the room. I didn't expect to interview two of the most important bassists at once; such luck is rare. Jaco and Victor had met just that day, but they seemed to be longtime friends, teacher and student, based only on previous brief, backstage encounters.

After rounding up some beer, Jaco dove into the photo shoot, thereby giving me a chance to rethink the questions I'd prepared.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Who is Jaco Pastorius? I knew that he had recently left Weather Report, and the memory of his wonderful concert with his own orchestra, named for his recent self-produced Warners album, Word of Mouth, was vivid. But nothing I'd read prepared me for his wit and insight, combined with the slightest hint of urban anger.

Although now living in Florida, John Francis Pastorius was born in Philadelphia 31 years ago. He moved to the Fort Lauderdale area at age eight, and in his teens developed his skills as a player (on several instruments) and arranger, becoming an in-demand bassist for Wayne Cochran and his C.C. (Chitlin' Circuit) Riders, and other acts passing through South Florida. He wrote charts for the University of Miami stage band, and taught bass there for a time.

His first album, Jaco Pastorius, was released very soon after he joined Weather Report in 1976, replacing Alphonso Johnson in the premiere fusion jazz ensemble. Jaco then guested on Joni Mitchell's Hejira album; here his new, thick bottom sound was as much part of the songs as Mitchell's voice – and she has continued to collaborate with him, notably on her tribute album to the late bassist and composer Charles Mingus.

Jaco's first album on Columbia with Weather Report was Black Market; Heavy Weather showed his impact, featuring a bolder band sound, largely due to Jaco's bass playing, writing and production work. Birdland from that album became the closest thing to a Top Ten hit for Weather Report, Jaco's contribution – a deep bass riff – figuring heavily in the mix.

He also became the showman of the group. One of his tunes described his music to a degree: Punk Jazz was not an attempt at jazz by a non-player (We've heard plenty of those since then) but a real jazz player's stab at a brave new music, a fusion with energy but without overkill.

Somewhere along the way, Jaco became the state-of-the-art electric bass player. To be more accurate, he pushed the state of the art to the point where he defined it. Six years later, he remains the measure of any electric bassist's accomplishments, whether Jaco is actively playing or not.

What he did with his instrument was expand it way past its original function of merely supplying the harmonic underpinning to a composition. While there were other electric bassists with the technical ability to do more, Jaco was probably the first to make the listener aware of a musical idea first, and the instrument playing second.

In fact, one really didn't notice that it was a bass at all; it could have been a guitar or a synthesizer or an electric piano he was playing.

Victor Bailey supplied the history: "If I may interject, the thing that happened was: Stanley Clarke says, 'I don't want to be in the background and be a bass player; I want to play some music.' Then Alphonso Johnson says, 'Okay, but I can do more with the bass.' And then Jaco says, 'Hell with being a bass – let it be whatever I want it to be!'" Victor himself has the hardest act to follow in bassdom.

What he did with his instrument was expand it way past its original function of merely supplying the harmonic underpinning to a composition

As a matter of course, Victor supplied some of the best commentary of the evening, as thoughts and jibes bounced between the two bassists. What was amazing about the duo was the camaraderie between them, considering that this was the first time they'd spent together.

You might think that Jaco and Victor would not be so chummy, one replaced by the other in a world famous, often recorded, and from its inception all-star band. This wasn't the case at all, though. Jaco is still chummy and connected to, if critical of, his former bandmates.

"I have not left Weather Report, and I am not 'Miscellaneous Personnel,'" he maintained. "Victor, I guess, is going on tour, and he's a very lucky cat to get that position."

"Joe Zawinul does overkill, and his technological overkill sucks, but there's no friction between us; I just say, 'Look,' and that's it. Do you have any idea how much music I learned from him? I played a D-seven-sus-nine for Joe once and he said, 'Hell, that sounds terrible; only Duke Ellington can do that!'"

Jaco continued, "One of the important things Joe taught me is that the media actually is helping you if you permit them to help you."

Let's help him clarify: some critics felt that Jaco was getting too big to be the bassist of Weather Report, that his conception of music overstepped his ability to be a team player. He said, "My concept is not bigger than Weather Report. I am Weather Report. It comes through me; I do not create nothing. It comes from being a child and listening to the radio every day of my life.

"See what happens: Joe Zawinul on the planet today. And Joe knows what he wants – he's an Aryan, he's Germanic and I don't care if everybody knows it. Joe Zawinul can play like nobody! Joe Zawinul and Toots Thielemans, in my opinion, are the only Europeans who can play rhythm-and-blues.”

Composer/keyboardist Zawinul and saxophonist Wayne Shorter are, of course, the founding members of Weather Report; guitarist/harmonica virtuoso and whistler Thielemans contributed his composition Bluesette to Jaco's Word of Mouth.

I will say one thing: I invented the electric bass, and everybody knows it

Jaco Pastorius

Jaco still harbors a warm ambivalence toward the band he was with for six years and half a dozen albums, including Mr. Gone, 8:30, Night Passage and Weather Report. He implies that their business sense never matched the quality of their music or their personal relations.

"My momma told me when I joined Weather Report, 'They've got the worst managers in the world.' Joe Zawinul and Wayne Shorter are my best friends, and Herbie Hancock and Tony Williams, too. I mean, they will never lie to me. If I need some help they tell me right to my face. And that's what nobody understands. You see, I grew up on the tracks; to me, white and black – there's no difference, bro."

What about Jaco's contribution to the electric bass? He took time to talk about the fantastic Chromatic Fantasy – a transcription of a Bach organ piece he performed on electric bass on Word of Mouth.

"I will say one thing: I invented the electric bass, and everybody knows it. The Chromatic Fantasy, that don't mean shit. I just want to play the blues – in F," he laughed.

But he plays it fast. This interchange began:

Jaco: "I don't play fast!"

Victor: "When you listen to a person whose objective is to play fast you go, ‘Wow, That guy can really play fast.'"

Jaco: "I have never tried to play fast in my life."

Victor: "But when you listen to someone like a Jaco, and you're a musician, you hear the music. I think his objective was to learn the piece, not 'I'm gonna play this fast.'"

Jaco: "I practiced Donna Lee [his version of Charlie Parker's chop-busting bebop standard is on his eponymous first LP] and the Chromatic Fantasy for eight years before I would play them in front of anybody.

"When I first did the Chromatic Fantasy originally, I did not use an open string. It was so hard, but I did it because I was such a purist and people were always putting me down for being an 'electric bass player,' though I was so pure. I'm an acoustic musician. Mister V. said it earlier: Nobody understands how much we are correcting the music world.

I have never tried to play fast in my life

Jaco Pastorius

"Look at Sting [he pointed to the cover of an old issue of Guitar World], Sting is a playing mother! 'Cause he and I know how to treat the bass. The bass is the number one instrument in the world, because it hits the sound right where it belongs.

"Hey, man," he grinned, "all the greatest bass players come from Philadelphia: Alphonso, Stanley, Victor, me – we're all from Philly. It's the City of Brotherly Love!"

Since we were talking about bassists, I asked him about the famous Fender he uses, sunburst with the frets pulled out. That bass, although looking rather abused, sounds like no electric bass before it.

Even other bassists had thought it was an acoustic bass, when their backs were turned away from the stage or recording booth. Jaco played it during the photo session ("You never know, one of these shots might work!” he joked), and when I put my ear near it, there was the sound! I tried to get him to discuss his instrument – it's almost a Jaco trademark.

"Ninety dollars with a case! The most I've been offered for this bass is $80,000! That was in Europe. When I got this bass, I'll show you right here, these are the only scars I put on, just my thumbs. Everything else was exactly like this, just like I got it. I throw this thing around, I do flips on it, but I've never, ever, hurt this bass, ever! It looks like I demolish it every night, but I've never touched it; I've had it now for eleven years.

"I own 245 basses. In performance I have three or four basses on stage nobody knows about – not even Zawinul knows it sometimes. I'll take a bass I bought for fifteen bucks that day (and nobody knows it) and do a Pete Townshend or Jimi Hendrix routine, lighter fluid it and all that. Man, that's the easiest thing in the world!"

I asked him if there were any special tricks to the bass that made it sound that way – acoustic – since live he uses an effects rack – basically a compressor, a fuzz tone and a digital delay, put on infinite repeat for his climactic renditions of Purple Haze.

"The secret to the sound is to drop it on the floor!" he answered. "As I told you, ninety bucks with a case, and the frets were out. See this shit that looks like somebody chewed it up? That's the way it was when I got it. Petit's Poly-Poxy, that's what I put on the neck, but that shit won't go away."

Jaco hasn't put out a solo album since Word of Mouth and the last Weather Report album with him on it was released over a year ago. He has recorded much more than he has released, so he does have a backlog of tapes, some of which must be interesting, indeed.

"I have a record you will not believe," he claimed, "Holiday for Pans, which I adapted from David Rose's Holiday for Strings and arranged for Othello Molineaux, the steel drum player who's with me on Word of Mouth. And I have about 24 master tapes that I paid for myself. [Holiday for Pans would eventually be released in Japan in 1993, six years after Jaco's death, after it was rejected by Warner Bros.]

"You don't understand; everybody's gotta give respect to the music industry, but you have to know how to deal with the mothers, 'cause they're just like us: they care about music, they're good people, but you've got to be ready to deal on their terms. I am commercial. I don't complain anymore 'cause I can deal with it."

Then, a turnabout: "The reason I don't record enough is because I don't record enough, I'm an American Indian; I don't believe in photography or recording, I like to play everyday live!"

Again, a switcheroo: "Sometimes I have a very bad point of being too obnoxious. I am not too obnoxious. I mean, I just try to make things more peaceful. Me being obnoxious makes a lot of things more peaceful.” Snap, snap, goes the camera shutter.

People do not understand how hard a jazz musician works for a living. I'm not putting nobody down, but I'm telling you nobody understands how hard jazz musicians work

Jaco Pastorius

Jaco may be the greatest living electric bassist, but he certainly isn't the richest. He explained the reality and the reasons for this situation: "People do not understand how hard a jazz musician works for a living. I'm not putting nobody down, but I'm telling you nobody understands how hard jazz musicians work. Jazz is not big in the US, because the States are too worried about Pac-Man and The Police."

Victor affirmed Jaco's point of contention: "And the record companies, most of them, want to sell us a million records, instead of selling us significant music."

Jaco: "I don't want to sell shit. I want to do what has to be done. I'm a musician. And musicians are the peacemakers."

Is there a chance for a solo electric bass LP anytime soon? Jaco said no, for several reasons: "Because the timing ain't right and Victor hasn't learned how to play it yet and Jimmy Blanton's dead!" Blanton was the Duke Ellington Orchestra bassist largely credited with turning the acoustic bass into a soloing instrument.

So I asked Jaco how he sees himself as a musician. He's been considered one of the most creative players to emerge in the '70s, and has been heralded as an innovator, but when confronted with those opinions he takes an evasive maneuver, one outrageous statement after another, leading to a truth:

"I am not an original musician; I am a thief. Like Igor Stravinsky said, man, 'No good composers borrow – they steal!' I told the French press I want to be the Charles Aznavour of the bass – I am a very bad imitation of Gerald Jemmott [Motown's masterful bassman]!

"You see, I rip off everything. I have no originals. Only animals and children can understand my music; I love women, children, music, I love everything that's going in the right direction, everything that flows... I just love music. I don't know what I'm doing!

"If I practiced reading for one week, I could sight-read anything, but that's not my thing. I'd rather go in and just be Jaco. I improvise all the time; hopefully, I think, I never play the same thing twice. I'm not a magician, I'm not a politician, I'm a musician. I have no goal. You don't get better, you grow. I am a musician, and I finally realized it!"