“At the beginning John Lydon really loved it, and there was a real sense that it was great. And then, of course, it got very dark”: Jah Wobble on PiL, going back to his P-Bass – and why he’s reworking Metal Box

The post-punk pioneer gets back to his P-Bass, which he thinks of as a lifeform, and prepares to rework classic album Metal Box on tour – without ripping off reggae

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

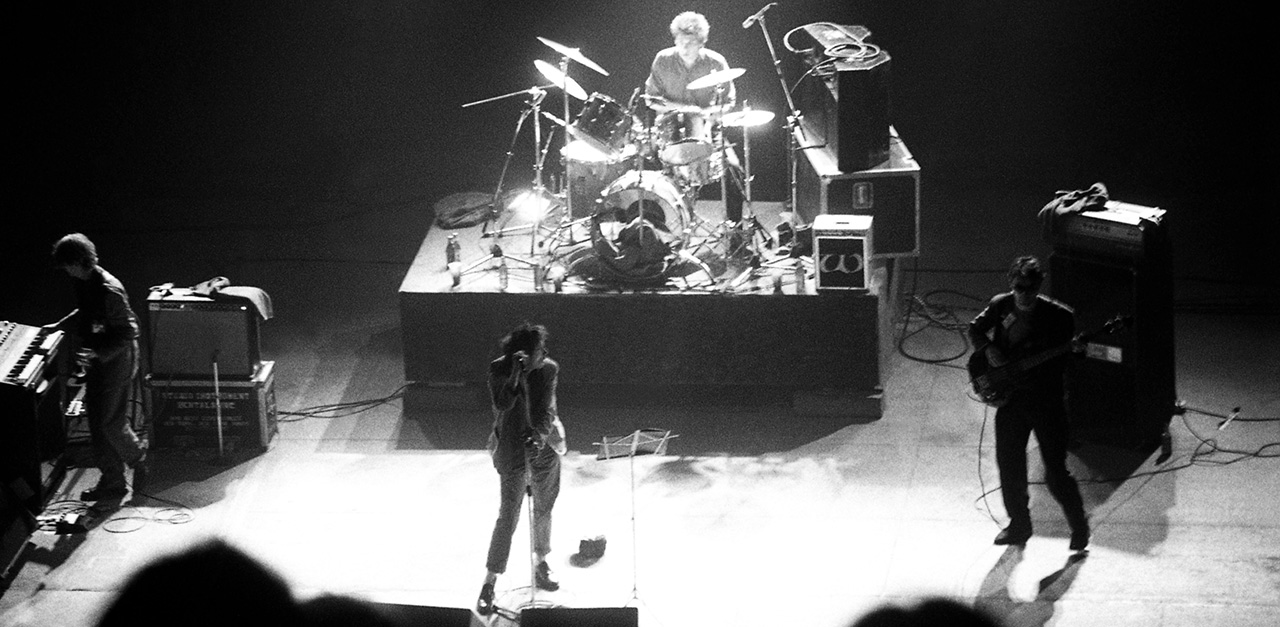

Born in Stepney, London, in 1958 and coming of age in the ‘70s, John Joseph Wardle was born to play punk rock, most notably as the original bassist in John Lydon’s post-Sex Pistols group Public Image Ltd.

Wardle had been renamed ‘Jah Wobble’ by Pistols bassist Sid Vicious while they were both members of The Four Johns. He’s is said to have kept the name because “people would never forget it.”

His association with Lydon goes back to the pair’s days at London’s Kingsway College – a connection that manifested itself in their music. Wobble tells Bass Player: “When I first toured America with Public Image in 1980, there was a spontaneity to that band that you saw for better and worse.”

Although he didn’t stick around for long, he appeared on Public Image: First Issue (1978) and Metal Box (1979) – two groundbreaking post-punk odysseys. Metal Box is particularly well-loved; which is why Wobble will mark its 45th anniversary on a tour called Metal Box – Rebuilt in Dub.

I don’t really want to be an expert – I want it to be open, fresh and in the moment. I don’t want it to be tired

“I’m back on the Fender P-Bass, and I think I’ve developed musically in a way; I’ve learned more stuff,” he says.

“The essence of me is still sitting down with an open mind, making a line, then keeping it very simple and straightforward, with no pedals or anything.

“I don’t really want to be an expert – I want it to be open, fresh and in the moment. I don’t want it to be tired. Sometimes the road can be like that; you’ve got to trust your repertoire.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

That trust is what gets him through the trying times, a lesson learned during his partnership with Lydon.

“You’ve might have to go on stage with a temperature of 102, but you’ve got to put on a show. But that’s great – you liven it up a bit and the adrenaline kicks in.”

What were the conditions like while you and John were working on Metal Box?

“I think the bass sound came because I didn’t like it when we used the big studios with a big fancy desk. I liked being in a weird little basement in Chinatown, London, with low ceilings; that gave a good bass sound. If I was doing a bass line it would resonate around, and I’d find the parts of the room that resonated the most.”

What else added to your bass tone?

“You always need a bit of compression on it, to be fair. But basically, you just turn the bass up. I’m serious – a lot of it is in the phrasing, and I was never afraid of that. I think most people are afraid of the power, but for me, it wasn’t just an instrument; it’s a fucking lifeform.”

At the beginning John really loved it, and there was a real sense that it was great. And then, of course, as we moved into ’79, it got very dark

You’re injecting dub into the mix on this tour – which isn’t that off base considering your influences back then.

“Linguistics is always insufficient; but I don’t mind the idea of being called ‘post-punk.’ For me that meant heavy bass, kind of being influenced by the sonic quality of reggae – but not ripping reggae off. I never wanted to do that.”

Another factor was John bringing the Sex Pistols’ musical mindset.

“Oh, yeah, I was excited. At first it was a wonderful feeling, and we actually started out a bit conservatively and had structure and a bit of pop sensibility. I think a lot of people thought, ‘This is fantastic; it’s gonna be a great band.’ Then we kind of lost patience with making songs, and began leaning into a heavier theme with Metal Box.”

It’s been said that things went off the rails around then – is that true?

“At the beginning John really loved it, and there was a real sense that it was great. And then, of course, as we moved into ’79, it got very dark. There were drug issues around the band, and the unpleasant people started hanging out. It was the kinds of things that happen with bands. Those things just killed PIL because we went through them very quickly.”

Was the band well-positioned to handle sudden success?

“I suppose the business wasn’t looked after properly. If we’d had a proper manager – sort of a hard-nosed guy – and we’d been on a record label other than Virgin and been given proper advice, maybe. But we were unconstrained, you know; we could do what we wanted and kind of get away with it.

Metal Box is really special. I was really fed up with it, fed up with the guys and the bandwidth; I had to move on

“But all the dark stuff was under the surface. It should have been all about music and art. It was great at the beginning, but within six or seven months it got a bit mean. There was a lot of fucked up, nasty business.”

Is that why you left PIL after just two records?

“In two years or so, we did less than 20 shows – which is ridiculous, isn’t it? They couldn’t get up off their asses, or whatever. So I got very bored with it and wanted to move on.

“But one of the good things was I had access to a lot of studio time, so I was able to make solo records, which I made some money from. I was also really excited to learn about studios; I fell in love with studios and making music.”

Metal Box must still mean a lot to you.

“It’s a great record – it’s really special. I remember that I was really fed up with it, fed up with the guys and the bandwidth; I had to move on. When I left PIL I got absolutely lost in music, and I didn’t realize Metal Box was a really special record.

“I hate to give John any credit – just joking! – but his lyrics aren’t really lyrics; they’re groups of words in light prose. Virgin kind of let us do what we wanted, and there wasn’t proper management, so you end up with this really strange bloody record. If we hadn’t been in a band, people wouldn’t think we were special, just really odd!”

There’s some risk in reworking a classic album on tour.

“There’s a lot you can rework. It’s really great to get your teeth into because it kind of suggests so many things where there’s these tiny little fragments of sounds. It’s like reimaging what the recipe to that is, or something, and developing it from there. Like taking a strand of DNA and evolving it.”

In doing that, have you learned anything new about the record or your bass lines?

“Really, the question you pose is: am I a better bass player? I think I am. But as a musician, generally, I’ve learned a lot of stuff and developed, and that’s what I’m bringing to the table while keeping the raw power of it.”

Which songs are you most looking forward to digging into?

“Albatross – I fucking love it when the heavy metal guitar comes in; and yet it’s still recognizably Albatross all fucking day long. So that’s still there.

All these years later, I say my 60s are as good as my 30s; I’m very happy

“But I’m almost at retirement age… at one point, if you’d asked me to do Metal Box I would have laughed! But I’m way past that now. All these years later, I say my 60s are as good as my 30s; I’m very happy.

“I’m happy to be able to look back in a relaxed way and revisit the music that I helped create all those years ago. It’s an amazing feeling.”

- Jah Wobble’s North American tour kicks off on July 10.

Andrew Daly is an iced-coffee-addicted, oddball Telecaster-playing, alfredo pasta-loving journalist from Long Island, NY, who, in addition to being a contributing writer for Guitar World, scribes for Bass Player, Guitar Player, Guitarist, and MusicRadar. Andrew has interviewed favorites like Ace Frehley, Johnny Marr, Vito Bratta, Bruce Kulick, Joe Perry, Brad Whitford, Tom Morello, Rich Robinson, and Paul Stanley, while his all-time favorite (rhythm player), Keith Richards, continues to elude him.