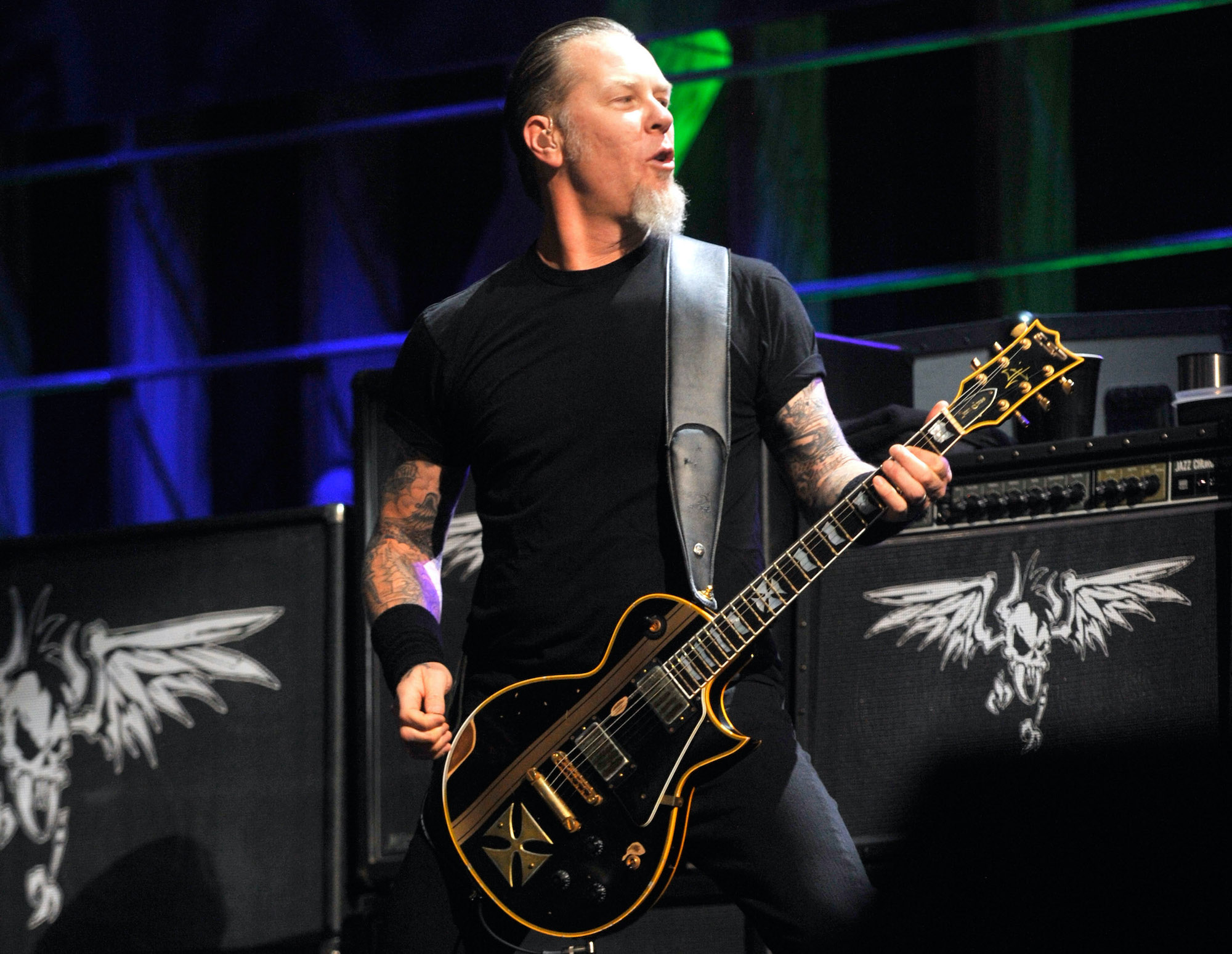

James Hetfield: "I’m on this eternal quest to get the best guitar sound in the world, but my vision of what is 'the best' changes every time I go into the studio"

In this 2008 GW interview, Papa Het discusses Metallica's new approach for Death Magnetic, and why he always comes back to his Electra white V, plugged into a Mesa/Boogie Mark II C+

The following interview with Metallica's James Hetfield was featured in the December 2008 issue of Guitar World.

With his black work shirt, black jeans and big, black motorcycle boots, James Hetfield looks a little like a garage mechanic working the graveyard shift at a funeral home. His thoughts, like his outfit, are dark.

“The theme of our new album is that we’re all gonna die sometime,” he says with a cruel little chuckle. “Just like the poles of a magnet, some people are drawn to death and others are repulsed by it, but we all have to deal with it. Lyrically, it started as a bit of a tribute to [Alice in Chains singer] Layne Staley and all those who’ve martyred themselves in the name of rock and roll. But it grew and evolved from there.”

Given the morbid nature of Metallica’s ninth studio album, Death Magnetic, it is ironic that the recording represents something of a musical resurrection. While the 10-song recording does not slavishly imitate the group’s late-Eighties triumphs like Master of Puppets or …And Justice for All as rumored, it is not afraid to hark back to those glory days.

Jammed with adventurous song structures, devilishly complex instrumental breaks, whiplash tempos and numerous guitar solos, Death Magnetic is the aggressive, old-school thrash epic longtime Metallica fans have been dying for. It is, in Hetfield’s words, “more alive and has more lift” than anything the band has done in a long time.

The Het is the Fonz of metal – one of those rare dudes that radiates an imperturbable, unflappable “cool.” But over the past few years, even Metallica’s singer and master rhythm guitarist has wrestled with his share of uncertainty.

“Yeah,” Hetfield says, “The road gets cloudy. Life gets cloudy. The whole ban on guitar solos on our last album, was kind of a…”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Falling short of calling it a “mistake,” it is clear that Hetfield has some misgivings about his band’s previous studio effort, St. Anger. Featuring repetitious, grungy drop-C riffs and a surprising absence of shredding from the band’s virtuoso lead guitarist, Kirk Hammett, the controversial 2003 release was Metallica’s least successful studio outing.

“I wasn’t a big fan of not having any solos on the album,” Hetfield says. “Being a singer, there are very few songs I listen to just for the solos, but the solo is the voice for a little while. And not having that element on St. Anger was somewhat – I don’t want to say ‘boring’ – but it made the album pretty one-dimensional.

"Either the singing was on or the riff was on. Or that snare sound was on,” he says laughing, referring to the distinctive tuning of drummer Lars Ulrich’s kit, which became the signature sound of the album.

At the same time, the frontman defends the validity and sound of the work, which he feels directly reflected his state of mind following his much-reported stint in rehab.

“We tore Metallica down to a bare-bones skeleton, and it was not unlike what I went through in my personal life. During that period I was breaking down and rebuilding. St. Anger is exactly what it had to be and needed to be. With our new album, we’re back into our earlier mode, where the songs are more of a ride. It’s a lot more fluid.”

Helping the band get back on track are superstar producer Rick Rubin, (noted for his productions for Johnny Cash, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Slipknot and Slayer, among numerous others) and bassist Robert Trujillo, who took over bass duties for the group in 2003 (longtime bassist Jason Newsted quit Metallica in early 2001 to pursue other projects). The result, Hetfield explains, is a work of new “power, excitement and clarity.”

As for his fabled rhythm playing, it’s never been harder, faster or more precise. Warming up to the topic, Hetfield, who is often said to have the best right hand in metal, says, “I’d much rather talk about guitar playing. I hate it when people ask me about my lyrics. I always feel like telling them to just go and read them,” he says with a laugh.

So with that, we begin our conversation that encompasses life, death and Hetfield's “eternal quest” to get the world’s greatest guitar sound.

How would you describe this record?

"I guess I would say that it’s a look backward – taking the essence of our earlier style and playing it with our current skills. It’s impossible to completely regain your innocence or virginity. When we recorded our first albums, we had no regard for authority or for the way things were supposed to be. We’d walk into a studio and we’d play what we knew and that was that.

"Some of the engineers would complain and say things like, 'You can’t hear the vocal,' or 'You can’t hear the guitar… what’s that sound?' And we’d say, 'That’s us! Record it, please.' [laughs] We tried to capture that attitude again. It’s one of the reasons we chose Rick Rubin to produce the album. He’s good at capturing the essence of the artists he works with."

Rick is great at taking a classic artist like Johnny Cash and helping them recapture what made them great in the first place.

"Yeah, presenting them again and giving them another chance to speak. Especially Johnny Cash. Johnny was totally screwed by his record company and kind of disappeared. It’s like, 'Come on, Johnny Cash is America. This has to rise to the top again, somehow. Gotta fly the flag!'"

The new album references the past, but it has its own character.

"I’d like to think every one of the albums has its own unique and distinct sound. Some might be harder to listen to. Listening to St. Anger is somewhat of a chore for me. [laughs] It’s cool because it’s raw and in your face, but it has just one dimension. You know, 'This is anger, and here it is.'"

How important is the guitar sound to achieving that character?

"Very important. I’m on this eternal quest to get the best guitar sound in the world, but my vision of what is 'the best' changes every time I go into the studio. Sometimes my goal is to make my guitar jump out, and sometimes I want it to lay back. It all depends on what we’re trying to achieve with the album. But getting the right sound is essential. I want to feel what I’m playing. When I finally arrive at that sound, the songs get written and played."

So how did this album begin?

"It began by reviewing lots of music we had written on the St. Anger tour. We usually play a little bit before each show just to loosen up. Invariably, someone will have a riff and we’ll start recording and jamming. The beginning of this record was sitting down and listening to all of those sessions.

"What was interesting is that the music would be very different depending on who got to the warm-up room first. Different pairings would create completely different ideas and grooves."

So the writing usually starts with an instrumental riff?

"A guitar or drum riff always starts the song. That’s the seed the songs rise from."

Each song on the new album features multiple riffs and as many as three solo sections. Did you ever worry about going over the top?

"Well, we usually fall victim to ourselves in that respect. We always think there’s not enough or there’s got to be more, and most of the songs on this album are pretty long. However, we’re not too concerned. We’re pretty sure radio, be it satellite or whatever, will play them.

"The one thing I struggle with these days is quality control. In the early days we only had to write between eight and 10 songs per record, so if a riff wasn’t good we just threw it away. But that started to change when we were writing Load and ReLoad. If a riff wasn’t working, instead of throwing it out we’d explore it and try to take it as far as we could to see if there was anything there. We’d end up recording 20-something songs, which was especially challenging because I had to write lyrics for all of them.

"On St. Anger, the process was even longer; we went through two writing cycles. On this one, there were 16 full CDs of ideas with 30 to 40 ID markers on them. We’d name each riff. Here’s the 'Fargo' riff. Here’s 'Casper.' Here’s whatever."

Where would the names of the riffs come from?

"It would get pretty abstract. For example we called one 'Jim Bag' because the riff reminded me of a punching bag, but it also had a [guitarist] Jim Martin–Faith No More feel. So you shove these words together and you name the riff. And you’d remember what riff it is."

On the first few records, Metallica were inventing a new form of metal that evolved into what we now call “thrash.” It was a very internal process. Then in the Nineties, you allowed more outside influences to affect your look and sound. Death Magnetic seems like a return to your original impulses.

"Maybe. You’ll probably get a different answer from each person in the band. Lyrically, I write what I feel. It’s as simple as that. I’m not looking around saying, 'Hey, this type of lyric is more popular these days.'

"But there is no question that we pay attention to the outside world when the bar has been raised sonically. One of the reasons we wanted Rick Rubin to work with us is because we liked the sound of his production on the Slipknot and System of a Down albums.

"Rick and our engineer, Greg Fidelman, brought our sound to a new level. There’s power, there’s excitement. It feels alive, but you can hear everything. I really believe that we’ve always been our hardest critics. Our attitude has always been, It better be good, or else we’re not gonna put it out. But there have been times when we probably felt less like that."

I know you’re a singer, but your rhythm guitar playing had a huge impact on a couple generations of guitar players. How do you think your guitar playing has changed since, say, …And Justice for All?

"I haven’t really thought about it. I would say I’m probably a little more precise. It’s a little more important to me that the riff is clear. Back then I would just layer parts four times and make it wide. Now I’m more concerned about how sounds work. I’m a little more willing to put up with a sound that’s not completely great on its own but fits well within a song."

You’re considered to be one of fastest and most precise rhythm players in rock history.

[laughs] "It’s not hard for me to play fast. It’s just not. And I love that. It might take a little while to warm up to certain songs, but the fast down picking – the really fast double picking in the riffs, especially when I pick up the beat – is just fun."

Are your guitars set up a certain way to make it easier for you?

"I never really pay much attention to that aspect of it. Most of my guitars have been instruments that look cool. I’m not picky. I never think, Oh, this neck isn’t made of ebony, or, These strings don’t feel correct. It doesn’t matter too much. Now, though, I’m paying a little more attention to what strings I’m using because they help me stay in tune. But I just like playing fast riffs. It’s as simple as that.

"In fact, it comes so easy to me that maybe there was a time, like while we were writing the Black Album or Load, that I needed a different kind of challenge. But now it just feels good to go to that place.

"A lot of it has to do with playing my old guitars again. I’m actually using the white V and the old Explorers that I played on the first few albums. I’m also plugging into the Mesa/Boogie Mark II C+ that we used on all the early albums."

What made you crack open your old guitar cases and plug in your old amps?

"When we begin recording, we always start by trying out lots of new amps and guitars. I’ve often asked myself, Why do we do this? The answer is usually, Because I want to and I can. [laughs]

"I always think I can make my sound better. So you get every amp company in the world coming in with their latest product, including prototypes of things that haven’t even been built yet, and at first it’s like going to guitar heaven. But then I start plugging everything in, and by the time I whittle it down, I’m back with my Eighties Mesa/Boogie 'crunch berries.'"

But what got you back into using your white V?

"That amp with that guitar is magic. No other explanation. It’s not the beefiest or fattest sound, but the mids just come alive."

How many tracks did you use for rhythm guitars?

"We’d have three or four amps going at the same time. We’d just morph between the tracks to see what sound felt best for the song. We used an Ampeg for some things, and I’m still using my Mesa/Boogie TriAxis preamp, but the C+ usually ended up taking over the left side [of the stereo spectrum], which is my side."

It’s not surprising that you still gravitate toward your early gear. Those are the instruments that you really know. There is no way something new and unexplored is going to compete with that kind of relationship. When was the last time you got a new piece of gear and said, “I’m gonna spend a week and just work with it to find out what it can do”? You spent years with your V and your Boogie.

"That’s really true. And those early circumstances were powerful, too. I can remember when we first discovered Mesa/Boogie, back in the Eighties. We heard about this amp company right in Pomona, near where we live.

"When we first plugged in, we said, 'Oh, this is awesome. This is amazing. But it’s how much? Oh my God!' We couldn’t afford it back then. But when we finally got our hands on those amps in ’83 or ’84, around the time of Ride the Lightning, we spent weeks tweaking and working, adding pedals, adding this and that, just like you described."

And the white V – it’s not a Gibson V, right?

"No, it’s a Japanese knockoff. It’s actually the third guitar I ever owned. My first guitar was a swap-meet thing that I paid five bucks for and painted about 12 different times. I put Eddie Van Halen stripes on and all that stuff, like every kid did. And the second guitar I had was, like, a ’69 SG that some kid sold [to] me in high school for $200.

"I traded it for a PA because I wanted to be the singer, because everyone was looking for a singer back then. And then the next guitar I bought was this V.

"Somebody sold it to me as a Gibson V, and as a dumb kid I had no idea. Eventually it dawned on me: Oh, it has a bolt-on neck. It can’t be. Hmmm, why does it say 'Made in Japan' on it? [laughs] But I didn’t care. I didn’t have a care in the world. It’s a white V! It’s Michael Schenker, it’s Scorpions. That’s was metal: black pants, white V, go! I couldn’t care less that it was not a real Gibson."

It created your signature sound. I’m always fascinated with stories of people finding these basic tools and making them work to create something amazing. I think most great music comes from that. It’s not about having every tool. It’s about working with what you have.

"It’s the struggle. From struggles come great gifts. Even though you don’t know they’re gifts at the time. Later on they become that. ESP makes me amazing things – anything I want, but I still use that guitar. It’s a shitty Electra copy of a Gibson V from the late Seventies, maybe, early Eighties. And yet, here I am, holding it on the cover of Guitar World!"

That’s because it is your guitar.

"I know what you mean. Well, the thing is, it’s very strange, but I’m just discovering that. Somebody recently approached me and said, 'We’re putting a coffee table book together. Bring some of your most signature guitars out.'

"I started thinking about it. I actually have my own new signature guitar made by ESP, but what do people know me from? Which instruments spawned my best riffs? So we pulled out the first Explorers ESP made for me – the 'So Fucking What' guitar, the 'Eet Fuck' guitar, the 'More Beer' guitar – and I just started playing them. It sounds cliché, but I put on these old shoes and they just fit.

"I thought, This is why I play this guitar. I’m searching so hard to have my signature stuff, and it’s back there! Turn around, dude – you have it! I’m grateful to have my eyes opened."

It’s an interesting parallel. You’ve done the same thing with your music. You started in a place, and then you explored all these different areas, and now you’ve gone full circle.

"But you don’t know until you leave. You don’t see home until you’re gone. That’s how it feels. And it’s a great feeling to come back home."

Your rhythm playing on this album is tight, but it’s less stiff and more “groovy” than on your early records. You’ve almost become the Keith Richards of thrash. Are you more relaxed and less self-conscious in the studio than you were in the early days?

"Oh, I’m still insecure. For sure! I’m always saying, 'It’s not tight enough.' People think I’m nuts. It’s something that absolutely haunts me. After we recorded Hit the Lights, which appeared on the Metal Massacre compilation – the one where Metallica is spelled with two Ts [laughs] – this guy heard the song and told me, 'Oh, the rhythms aren’t very tight, are they?' Man. That was it!

"That started my lifelong quest. That was the Holy Grail for me – being tight. Back in the early days, we were all competitive. Very competitive. We’d always say, 'They’re faster… but they’re not as tight.' That’s where we got our satisfaction."

If I’m not mistaken, most of the new album is in standard tuning. That’s a big change from St. Anger, which was in drop C.

"Yeah, it’s all A-440, except two songs that are in drop D. That was one of Rick Rubin’s things. That’s probably the biggest thing he contributed to this album. He’d always say, 'I want you to play in 440. Let’s hear what it sounds like.' And he found there was some tonal quality, not in just the music but in the voice, too, that he really liked. There was something in the struggle of me singing in higher keys that he felt was unique.

"I wasn’t very excited about it, because it was difficult for me. There might be some people whose voices don’t change after 27 years, but I would think it’s rare. So that was a little bit of a hurdle for me. But I was willing to go for it, and it really did work pretty well, especially in the faster songs. And playing faster in 440 is quite a bit easier."

Much of the current thinking is, I want to sound heavy, so I’m gonna drop my tuning. But that can also just as easily turn the music into sludge.

"I discovered that our sound was more alive, and felt younger, because it’s in A-440. It’s got a lift to it. Sonically, everyone was able to find his space in the mix a little better, and we sound fuller.

"None of this is to take away from playing in drop tunings. When you’re sitting in your room and you drop down, and you’re the only guy playing, it’s amazing. I’m the bass player and the guitar player! It’s like, who needs a bass player! But when you incorporate that into a band, it’ll work for a couple of songs, but a whole album filled with that can sound pretty flat."

Even though you’ve gone back to using some of the original tools, your sound has changed. Your sound is a little less brittle.

"Obviously, in the earlier days, my sound was scooped. We made a smiley face on the EQ, and that’s it. During the time of the Black Album we learned more about using the guitar’s midrange – adding more mids, getting a little more what I call 'bark.' The 'bark' is found in the low mids, where your guitar is very percussive and hopefully marries up with the drums and makes everything sound even punchier. It’s an element that has become pretty important to me."

How involved are you in the mixing or the engineering processes?

"During the recording process, we’ll all work and get the sounds we like as individuals. I’ll say, 'Here’s the sound that makes me play well.' Then, the engineer’s job is to make all our sounds live together properly. Sometimes there’s give and take, but my guitar is pretty important." [laughs]

Are you happy with the sounds?

"I’m very happy with them. And I’m pretty surprised at how we got them, too. We went a lot drier and used a lot less gain. When I chug, you feel the compression suck on the cabinet. Add the razory top provided by the V and the C+ – the combination works really well together.

"In the early days I played all the rhythm guitars and Kirk played the lead. Then things changed on Load and ReLoad; Kirk did a lot of rhythms. On this album we returned to the way we originally recorded. All the rhythm parts are me."

What did you learn from the Black Album on?

"On the Black Album we learned how to add muscle to our sound. On Load and ReLoad, I learned that when you write too many songs, your focus gets watery; it gets diluted. I hate that part of us. We know how to take an okay song and make it good. But the question lately has been, Do we have the discipline to dismiss an average song and say it’s not on the record? Do we know when something is not good enough?

"We used to have that discipline early on. And I attribute that to having blinders on – that fuckin’ attitude that says, 'Fuck that, it’s not heavy enough to put on the album.' In the Nineties we tried to embrace everything, and [producer] Bob Rock was good at helping us do that.

"Each time we did, we opened our eyes a little more, but the discipline kind of went away. We became craftsmen instead of destructors. So from Load and ReLoad, what I learned is that I can’t spread it out over 40 songs. I just can’t. I’d rather have eight powerful songs than 14 so-so songs."

That’s almost been the crime of the CD. The reason why a lot of those classic rock albums kick ass so much is because there’s eight tight songs, not 13 loose ones.

"Lars and I battle constantly about that. I’d rather have eight that are going to get people hard, and he’ll go, 'Let’s play ’em all.' I don’t want fluff. I don’t want extra stuff. I don’t want bonus tracks. I don’t want, 'You gotta give ’em more.' Fuck that. I want to give them good. And if it’s good, they’re gonna want more. It’s as simple as that. That frustrates me a lot. And he and I go back and forth on that."

You’ve talked a bit about Diamond Head and the music that inspired you when you were first starting out, but is there somebody that you’ve listened to in the past 10 years, whether it’s a new or old artist, that you appreciate on a guitar-playing level?

[Long pause] "There are certain guys who obviously inspired me to play guitar. I loved certain bands. Ted Nugent and Aerosmith had some riffs, but it was more the Judas Priests and the AC/DCs that got to me because the rhythm guitar was such an important part of their sound.

"I’d listen to somebody like Malcolm Young and think, This dude’s driving the train right now. And that would be exciting. These days, there’s been such an amazing resurgence in guitar talent – and not just guitar but drums, keyboards, singing… It’s unbelievable."

Yeah, that Pro Tools guy is pretty good!

[laughs] "Yeah. Mr. Tools? Yeah, he’s one helluva a producer! I hear what you’re saying, but I think there’s more to it. I think there are guys sitting in their bedrooms trying to imitate stuff that has been Pro Tooled to death, and they’re playing it naturally.

"Pro Tools is creating new monsters. It’s amazing how some of these guitar players are. It reminds me a lot of, say, when the Eighties happened and all of these amazing virtuoso guitar players like Yngwie Malmsteen were emerging, and there were plenty of bands that had amazing rhythm sections."

Are you talking about bands like Bullet for My Valentine and Avenged Sevenfold? Their arrangements are so big and complex that they are almost writing heavy metal symphonies.

"Right, right. You can probably put DragonForce in there. Bands that have two unbelievable guitar players and they’re playing all their parts perfectly in concert. And the drummer is keeping right up with them. There are drummers around these days that blow me away. And some of the stuff is very orchestral. It’s very dramatic and epic sounding. So a lot of that stuff is pretty inspiring.

"And then you get the bands that are really sideways – Meshuggah or Loincloth. They make me wonder, How in the fuck can you remember this song? How can you? It’s unbelievable. With some of this stuff, it’s almost too much and hard to listen to at times, but I’m just stunned. It’s a pretty exciting time."

It’s cool that you still keep up with a lot of the new bands. I like many of the bands you just mentioned, but in many cases the singers are the weakest links. You’ve got ’em whipped on that level.

"Think so? Well, we’re still looking for a singer. [laughs] If one walks in, we’re still looking. I’m just filling in for now. But then you have the other side of that where you’ve got some bands that can really sing and you hear them all on the radio. They’ve got these singers that are singing, basically, this poppy melody. They’re trying to sing it gruff, and they’ve got the heavy guitars, but it’s pop. It’s fuckin’ pop. And it’s driving me nuts. I’m so sick of it.

"That’s why I’m really gravitating to more of the stuff on Hard Attack, the real heavy station [on Sirius Satellite Radio]. Even though a lot of singers are hard to take, I’d rather hear something that’s alive. Something someone put some thought into."

The production on Death Magnetic sounds pretty organic.

"I’m not saying that things were not fixed, by any means. There’s a lot of that going on. But the key to that is to not lose the feel. A lot of times it’s the push and pull between Lars and me that’s either good or not. That’s a lot of it – the magic of the feel."

But you don’t feel any push and pull on some of the modern metal records.

"Well, for some bands it’s 'robot' all the way. But you know what? I love hearing that for a little while. I like to get blown away by the fuckin’ metal robot. [Makes machine-gun drum sounds] You know, stuff that is just hammering you.

"When you’re in your car rivaling some guy next to you, and he’s got his rap [makes hip-hop bass sounds] rattling his tuner car apart, and you’ve got the ’52 Oldsmobile and you’re firing machine-gun drums at him, it’s pretty cool to be able to rival that with some good sonics."

At the top of the interview you said you’d rather talk about the music, but your lyrics are pretty hard-hitting on Death Magnetic. What were you going for?

"I really wanted to focus on the crypticness of the Metallica lyrics. I wanted them to be somewhat anonymous but powerful. If you’re in that frame of mind, you’ll plug into it. I’ll put two powerful words put together, and sometimes I won’t know what they mean, but I’ll apply them to my life somehow.

"The thing I don’t like is when songwriters are blatant and they say things like, 'I wrote this song about this.' I like to put intense ideas together and let them morph into people’s lives and souls. The hope is that it can apply to other people’s fucked-up-ness. There’s nothing cooler than when people use one of my ideas to discover themselves. It’s their own therapy, in a way."

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away Brad was the editor of Guitar World from 1990 to 2015. Since his departure he has authored Eruption: Conversations with Eddie Van Halen, Light & Shade: Conversations with Jimmy Page and Play it Loud: An Epic History of the Style, Sound & Revolution of the Electric Guitar, which was the inspiration for the Play It Loud exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City in 2019.