James Jamerson or Carol Kaye: who played what? Uncovering the truth behind the Motown mystery

Academic and bassist Brian F. Wright details his research into Motown's contested history

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

We like to think we’re a fairly rock ’n’ roll bunch here at Bass Player: after all, the bass guitar is the coolest instrument on the planet, and it deserves to be played loud.

That doesn’t mean we can’t enjoy a spot of academic rigor when the moment calls for it, though, and indeed, we were fascinated back in 2019 by an article called Reconstructing the History of Motown Session Musicians: The Carol Kaye/James Jamerson Controversy, published in the learned Journal of the Society for American Music, and available for your perusal online.

This extensive analysis of a particular longstanding debate over who played what at certain Motown sessions in the '60s was authored by bassist Brian F. Wright, an acclaimed academic who holds the post of Assistant Professor of Popular Music at the University of North Texas in Dallas.

He’s also the recent recipient of the Charles ‘Father of Stu’ Hamm Fellowship from the Society for American Music. An expert on '50s and '60s popular music, Professor Wright dug deep into primary sources to try to resolve claims made by the noted session bassist Carol Kaye, now 86, that some of her hit basslines had been wrongly attributed to the late James Jamerson.

For the full list of alleged misattributions, consult Kaye’s website or her autobiography, Studio Musician (2016), and for background on Jamerson and his membership of Motown’s famed Funk Brothers session crew, see historian Allan Slutsky’s essential Standing in The Shadows of Motown book (1989) and documentary film (2002).

All three documents are worth investigation if you’re interested in this confused period in music history, when Motown – like many other labels – didn’t bother to credit their session musicians. Half a century and more later, that lack of credit has led to a constant debate about whether Jamerson or Kaye recorded certain bass parts, a debate which may be resolved – at least in part – by Wright’s excellent analysis.

Why did you write your article about the Jamerson versus Kaye debate, Professor Wright?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Well, this is a story that all bass players know, right? Regular people on the street don’t know this story. Some of them may have heard of James Jamerson because they saw the Motown documentary that Allan Slutsky put together, and maybe they’ve heard about Carol Kaye, but this is really a sort of Inside Baseball kind of debate. There are great books by Jim Roberts and Tony Bacon and others that are for a broad audience of bass players, but in terms of really detailed historical work that goes back to the sources, there isn’t much.”

What were your objectives in writing it?

“I asked myself, ‘Is there anything new to add?’ and ‘Can we solve this thing, or is there only pure speculation?’ Most of the time, these discussions happen in echo chambers, where people either love Jamerson or they love Kaye, and they speculate on what really happened, but nobody’s really trying to go back and dig into the historical record.”

How did you get started?

“The question that started me on this journey was, ‘What’s the history of this debate?’ I thought the controversy itself was so interesting that it was worth asking how we got to this point. By the time I got to it in the '90s, it was a long-standing controversy, so the first thing I wanted to do was to trace the history of that controversy. After all, Jamerson had been dead since 1983, so I wanted to find out who was still fighting this battle.”

What were the key moments in your research?

“I got two very lucky breaks. While digging into the record, finding out as much as I could, I got ahold of two key documents. The first break was that I was able to get all of Motown’s West Coast session musician contracts from the '60s. I think other people had tried to do this before me, but their efforts had been denied, or they weren’t successful for whatever reason. So suddenly, I now had hundreds of session musician contracts – a huge amount of material.

“Then, around that same time, Kaye published her autobiography, and one of the things she included in that book was a day-by-day account of her sessions. So now I had two really interesting pieces of new information that people before me didn’t have.

“I also knew people who could help me decipher those contracts, because the contracts can be a little misleading – you can’t take them exactly at face value. You have to decipher them a little bit.”

You’ve been sensitive to all the parties involved.

“Yes. I don’t want to diminish either of their reputations or legacies. My goals were not to bring Jamerson down a peg, or to say that Kaye was making it all up. It’s not their fault. I want to emphasize here that the problem doesn’t come from Kaye or Jamerson. It comes from the lack of information.”

So what new findings did you come up with?

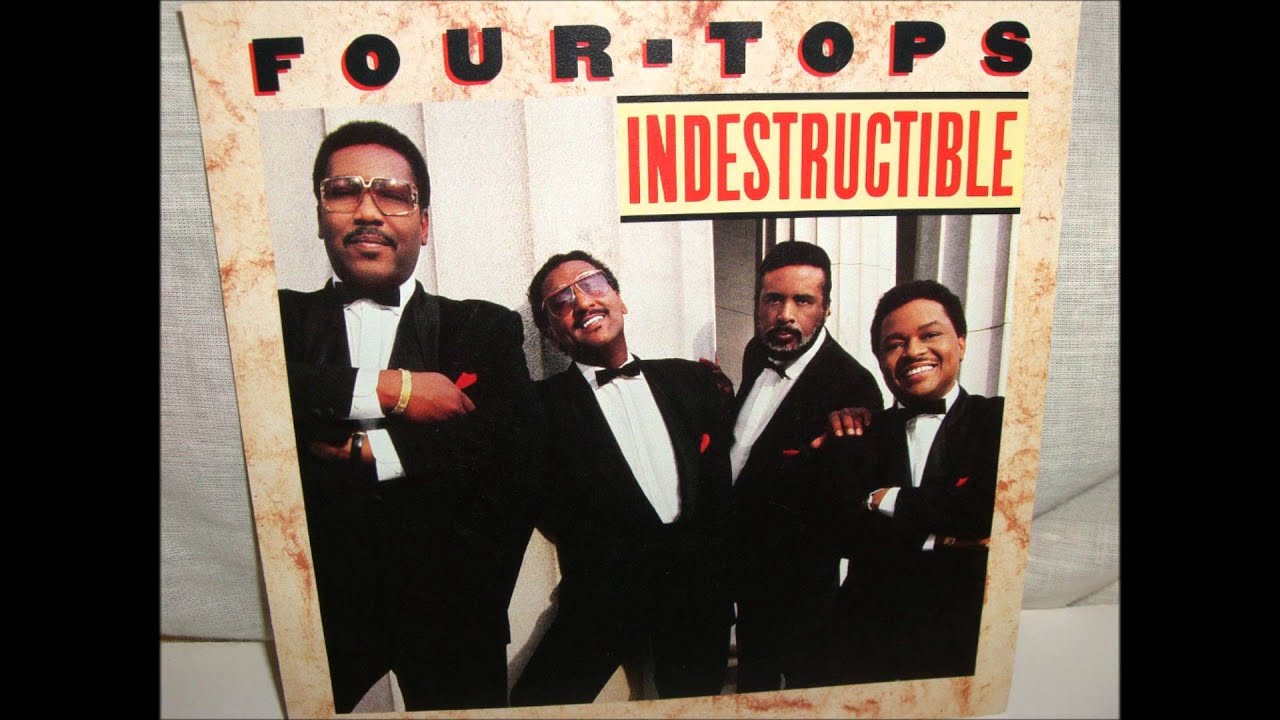

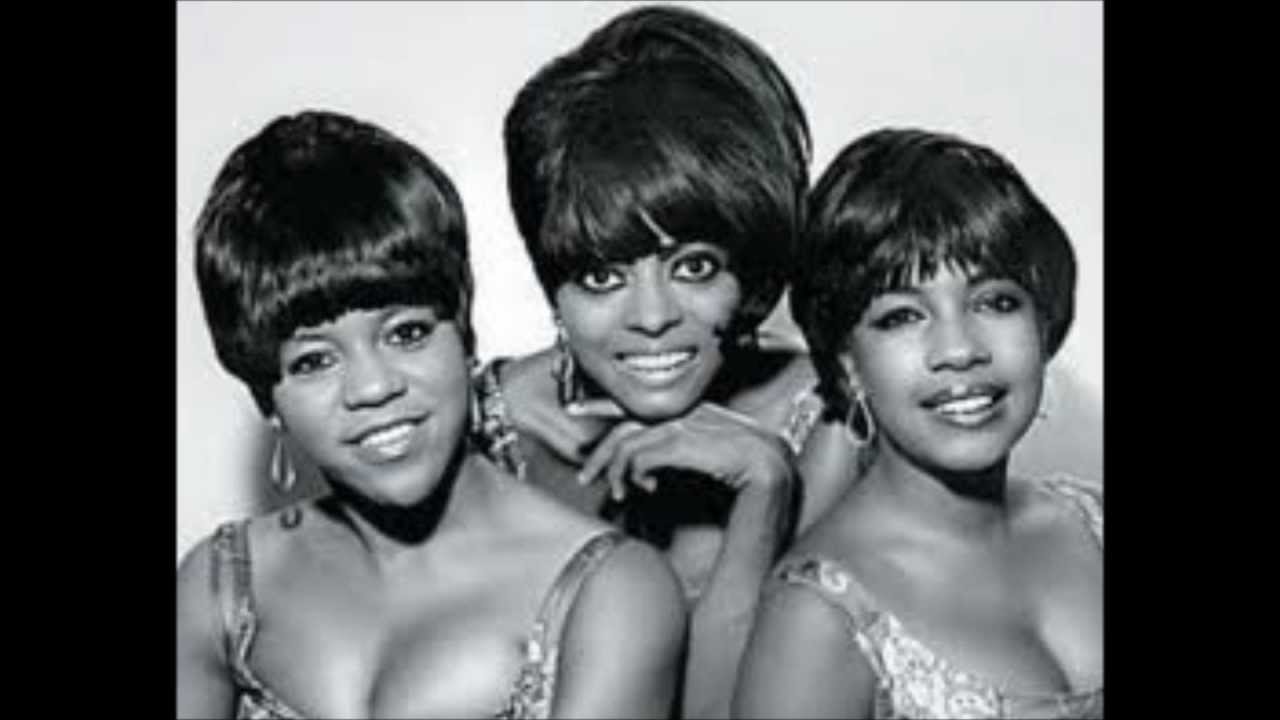

“I can tell you that Kaye is definitely playing on I’m Ready For Love by Martha & The Vandellas, Love Is Here And Now You’re Gone by the Supremes, In And Out Of Love by the Supremes, and Brenda Holloway’s You’ve Made Me So Very Happy. I can back those up 100 percent, and all of those were hits.

“I also attribute Someday We’ll Be Together, the Diana Ross & The Supremes version, to Kaye. Although I don’t have a contract for that one, there’s enough historical evidence to make me pretty sure. I think all of those are very reasonable, and yet, if you look at the list of Motown hits that she claims, there’s dozens more.”

Why is there so much uncertainty about this?

“Well, first, we don’t know much about Motown’s West Coast operations in the '60s. Second, Motown was constantly re-recording material. If you look at Motown albums from this era, you have the Supremes and Stevie Wonder and Smokey Robinson doing each other’s songs, and everybody doing everybody else’s hits.

“The singers were often not in the room when the session musicians were recording these songs – so if you’re the bass player, and you’re playing on what you think is Get Ready, for example, how do you know if it’s the hit version? Is it a re-recorded version? Is it an album version? Is it for a movie or for TV? And Motown also recorded lots of stuff that was never released. So you can’t really blame any of the bass players for not knowing if it’s them or not.”

We need to have a sense of what this job was like. This was a complicated job, where they were playing in a studio, three or four sessions a day, Monday through Friday

What’s the bigger picture here?

“I think, in general, what we really need is a clearer, more empathetic understanding of what it meant to be a session musician back then. We need to have a sense of what this job was like. This was a complicated job, where they were playing in a studio, three or four sessions a day, Monday through Friday.

“They were probably recording hundreds, if not thousands of songs per year, right? They were busy, and it was complicated. And the music industry treated them solely as hired guns, so they weren’t involved in what happened to a recording after they left the studio.”

We always assume that Kaye and Jamerson had completely different bass tones, but you explain that they’re way more similar than we think.

“You can’t trust your ears as much as you think you can. You have to realize that the Motown arrangements sometimes featured a 30-piece band. Sure, the bass is still prominent in the mix, but hearing whether it’s being played with a pick or not is tricky. And if you listen to any of those isolated Jamerson basslines, they don’t sound like they sound in the context of the band, because he’s overdriving the board and they’re a little bit distorted, especially in the low register.

“They sound crunchy in a way that they don’t at all in the full band context, and that’s a really good indicator that we can’t just trust our ears. And then people say, ‘Oh, but Kaye played with a pick, and you can hear it clicking.’ Sure, sometimes you do hear that, but other times you don’t, because her job was to be a chameleon. She was supposed to make any bass sound you can imagine. I think that’s a really hard thing for people to accept.”

Presumably the sad ending of Jamerson’s life makes people more emotional about him.

“Yes, because he died relatively young and unloved. That amplifies people’s emotions, and understandably so, because we all really admire what he did. Even towards the end of his life, they made the Motown 25: Yesterday, Today, Forever TV special (1983), which didn’t even mention the Funk Brothers.

“I tell people that I couldn’t possibly diminish Jamerson’s legacy, even if that was what I wanted to do. It’s such an amazing body of work – but one of the things that’s different about what I do, as an academic and a historian, is that I try to avoid mythologizing people. There’s a strong urge when we talk about James Jamerson to say, ‘He’s the god of the bass!’ But this makes for bad history and it can diminish the work of other bassists.

“My article has been posted on various bass forums, where it was largely well-received, but some people there do not believe my conclusions. Even when they’re confronted with direct evidence, they reject it because it doesn’t match the story that they want to hear.”

It’s so important that you’re doing this research.

“I hope it resonates. We have to ask, ‘What’s the best way that we can look at these things? What are the facts here?’ There are times when I am very clearly going against the way we normally tell bass history – but I think it’s important to go back and look at these things with fresh eyes.”

- Reconstructing the History of Motown Session Musicians: The Carol Kaye/James Jamerson Controversy by Brian F. Wright is available to read online.

Joel McIver was the Editor of Bass Player magazine from 2018 to 2022, having spent six years before that editing Bass Guitar magazine. A journalist with 25 years' experience in the music field, he's also the author of 35 books, a couple of bestsellers among them. He regularly appears on podcasts, radio and TV.