John Fogerty: “I practice ferociously. I’m grateful God allowed me to keep going with my love of guitar. It didn’t end when I was 15, and it didn’t end when I became famous”

The iconic singer-songwriter reflects on his Creedence Clearwater Revival-era gear – including “the best-sounding solid-state amp ever made” – and the long-awaited release of the band’s famed 1970 Royal Albert Hall show

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

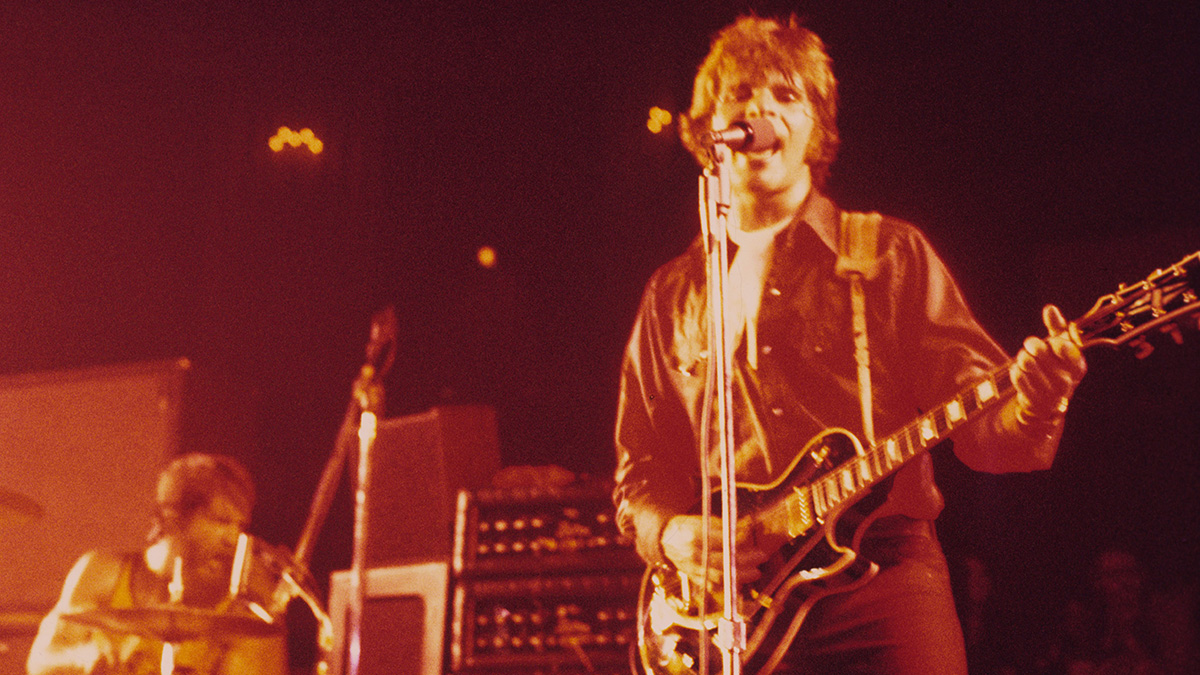

John Fogerty performed overseas many times throughout his career. But there is a mythical quality to his first tour of Europe in 1970 with his band, Creedence Clearwater Revival. In particular, the band’s April 14, 1970, show at the Royal Albert Hall is one of his favorite memories.

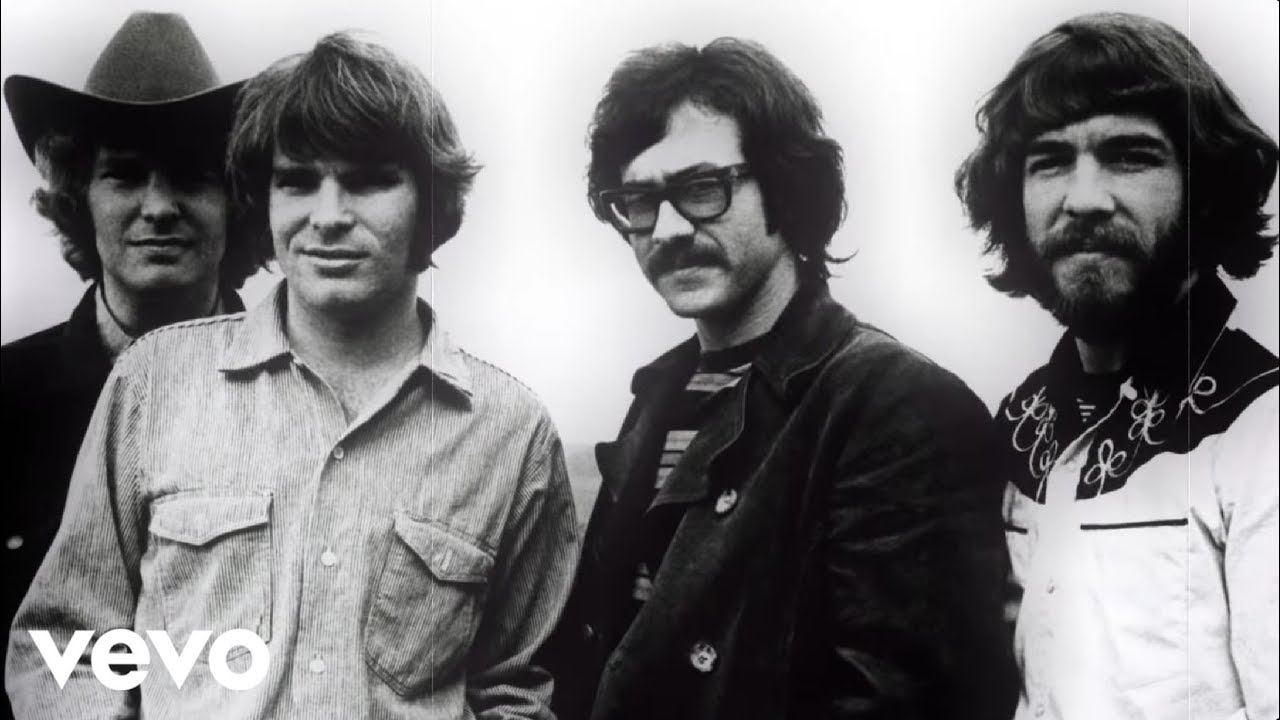

At the time, CCR – which also included John’s brother (and rhythm guitarist) Tom Fogerty, bassist Stu Cook and drummer Doug Clifford – were speedily making a name for themselves, already with five Top 10 singles in their first year together. Hits including Proud Mary, Bad Moon Rising, Green River, Fortunate Son and Down on the Corner showed off the band’s raw, high-energy, no-compromise rock ’n’ roll and tight chemistry.

The attention and success while touring the U.S. earned the band their first European tour. One of the shows was at the Royal Albert Hall, one of London’s most respected venues. The Beatles and the Rolling Stones were among the British groups that had performed there, and when CCR performed, it was just days after the Beatles had announced their breakup.

“I was writing songs like a maniac,” Fogerty says. “By the time we got to Europe, there’d already been four or five hit singles, meaning in most cases, both sides, and also maybe three or four albums by then. It was like a whirlwind… Getting to play the Albert Hall was certainly an honor. That was at a time when the band was still mostly positive and happy to be there. And all the energy was in a positive direction.”

This past September, Craft Recordings, a sub label of Concord, released a live album of the concert, Creedence Clearwater Revival at the Royal Albert Hall, as well as a companion documentary and concert film, Travelin’ Band: Creedence Clearwater Revival at the Royal Albert Hall.

The concert’s audio was mixed by the Grammy-winning team of producer Giles Martin and engineer Sam Okell and mastered by Miles Showell at Abbey Road Studios using half-speed technology.

The concert film is directed by Bob Smeaton and narrated by the Dude himself, Jeff Bridges. The film focuses on the band’s earliest years in El Cerrito, California, through their rise to fame, culminating with the Albert Hall show. It’s the only concert footage of the band’s original lineup to be released in its entirety.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

After 50 years of sitting in the vaults, fans are now able to revisit the concert. “I’m very happy for the fans,” Fogerty says. “It’s good that it’s finally coming out and that [people] can see it.”

GW recently caught up with Fogerty to reflect on the concert, the electric guitars, the amps and so much more.

We did just a manic, lightning-speed [trip] across Europe. We’d go from one country to another, the same way here in America, you go from Nevada to Arizona to Colorado to Chicago

How does the audio from the album release compare with what you remember about the show?

“It doesn’t sound as clear as I remember it. But back in the day, I did not listen to the audio. There was another album around that time that was recorded in Oakland [The Concert, recorded January 31, 1970]. I produced that, even though I didn’t get credit for it later when that album came out. But the sound was done very well on that one. This one sounds very live. It’s not as clear as what I remembered in my mind’s eye, but it’s exciting. The performances are good.”

What was the experience like going to Europe in your twenties with CCR?

“We did just a manic, lightning-speed [trip] across Europe. We’d go from one country to another, the same way here in America, you go from Nevada to Arizona to Colorado to Chicago. It was just amazing for an American to go there. I’m talking about a 24-year-old person.

“Half of your knowledge was in musical terms, but a lot of your knowledge was in historical terms, things you’d read about in school, or on your own, or seen in movies, that sort of thing. So you had very little snippets of information about each country.

“But, of course, you weren’t there long enough to really even get a sense of each country. Staying in one country, basically on a stage and in a hotel room for two days and then moving to the next country, really doesn’t give you much of a sense of what’s going on there.”

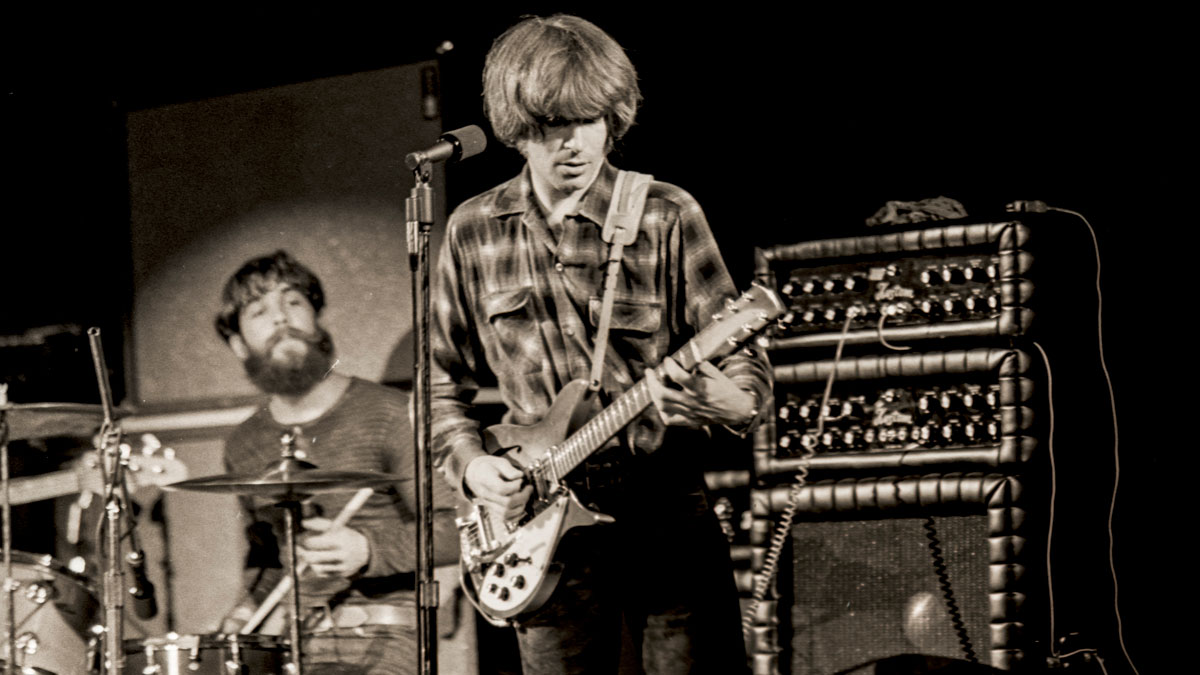

The guitars sound really great. What can you tell me about the gear you used for the show?

“[Tom and I] were playing through Kustom amps. Tom had a Kustom with a cabinet that had one 15-inch JBL [speaker] in it. And those were D130 outs, which is probably still the best rock ’n’ roll speaker ever made – and it hasn’t been made since. I was playing a Kustom K200A[-4], which was an amazing rig. It was roughly 100 watts and was solid-state, but it was probably the best-sounding solid-state amp ever made.

“It didn’t sound hard and cold and sterile the way so many other solid-state amps of that era sounded. And I’m just talking about when I used it clean… That amp had four effects built in; one was reverb, which I never used. It had a little remote pedal that you plugged in with a cord, and it had four buttons on it.

“The reverb button, I’d just click it on and off to make sure the reverb was off, because the amp was louder when the reverb wasn’t used. If you pressed reverb, the amp got a little quieter, and I didn’t want that. I felt there was enough reverb in the big room; I didn’t need to add more. But the other things – I used all of them. They were wonderful. It had what they called a harmonic distortion.

“It was basically a buzz tone, but it was built in. It didn’t come in front of the amp, the way you’d have to plug in, let’s say, a Maestro Fuzz-Tone at the time. Another gizmo that was built in was a treble tone-control thing. And it clicked to, I think, five different positions, like the way a Gibson – is that an ES-355? – the way they’d have had that little chicken-head knob that you could click to the different numbers.

“It had resistors built in that changed the sound. That’s what this thing on the Kustom amp did. I didn’t use it too much. The only time I ever used it, I think it was on Keep On Chooglin’. It gave it sort of a nasally ‘honky’ kind of a sound on one of the selections.

“Mostly I just like what a guitar sounded like straight into an amp. But by far for me, the most mind-boggling effect was the fourth one, which was a vibrato-tremolo effect – and you could blend between tremolo and vibrato. I didn’t want to use too much vibrato – vibrato meaning pitch-bending, so I’d turn it to the right a little bit, which was less vibrato and more tremolo, which is a volume effect.

“It would sound like a normal tremolo, but with the addition [of] a little bit of this kind of a spooky sound that came out of vibrato. It was a blend, and they were on the same clock, happening at the same time. They weren’t two completely unrelated sounds. I used that sound on Born on the Bayou and Midnight Special. There are so many songs I recorded plugged into that amp, using that vibrato-tremolo thing. Then I spent the next 45 years trying to get someone to replicate that.

“For the [Albert Hall] show, I was playing my Rickenbacker 325 that I had heavily modified. I’d put a Bigsby [B5] on it. I’d put a Les Paul pickup in the bridge position. I had put better tuners on it. And I had modified the knobs so that I had a master volume control.

“That guitar gave a very unique sound – if you listen to the beginning of Green River, particularly the single. I was also playing a black Les Paul Custom that I tuned down a whole step, down to the key of D. I did that because when I was growing up, I experienced a lot of folk music, especially Lead Belly, who played a 12-string, and he did that low tuning.

“That’s where I wanted to go with a Les Paul. The first time I ever tuned one down in a music store, [I] plugged it into a Fender Twin. I struck that first chord, which was an open E, which was coming out open D, and it made this incredibly wonderful sound, which is the basis of, let’s say, Proud Mary, Bad Moon Rising, Lodi, Heard It Through the Grapevine and so many others. It’s one of the more wonderful sounds I’ve been able to make.”

In the documentary, you made a comment about not feeling you were the greatest musician. Why do you think you felt that way?

“I didn’t feel that I was a virtuoso on guitar. I did feel I knew how to get a sound out of my instrument, which was pretty important. I had spent a lot of time in recording studios before Creedence existed, either with myself, or with some of the members of the band that became Creedence, or even with other people, and became very aware of what things sounded like.

I certainly felt that the other guys in my band, while we were good together, I didn’t think any of us was, let’s say, the best in the world, or even in our own country or our own state, at what we were doing

“I think musicians, especially guitar players, tend to be a humble bunch because it’s sort of the Wild West. There’s always some guy louder and faster and going to call you out in the street. And it’s just a matter of a flip of a coin if you get bushwhacked. So, the things that I knew are what I knew. And I liked how I sounded, but I also assumed that there were a lot of people running around that were better than me – and cooler than me and all the other stuff. I felt very comfortable within my own band.

“I certainly felt that the other guys in my band, while we were good together, I didn’t think any of us was, let’s say, the best in the world, or even in our own country or our own state, at what we were doing. To me, that didn’t matter. I thought it was much more important to sound good together.

“And I always used Booker T. & the M.G.’s as the best example of that. Because as much as I love Steve Cropper or Booker, I just felt that their real strength was how they sounded together. No one’s ever put up a groove the way Booker T. & the M.G.’s did. I think that remains the Mount Rushmore to strive for.”

What surprised you most while watching the documentary?

“It’s an incidental thing, but you’re looking at people who basically have left their hometown probably for the first time. At that point, we’d been all over the States but had never been to Europe. I think we sound typically colloquial, almost hillbilly, meaning we tend to say things that very young people say, not very sophisticated, really. And that surprised me.

“It was a quaint discovery. Because after you live another 50 odd years, hopefully you’ve learned a thing or two and had some experiences. And I know that just seeing myself, I go, ‘Oh.’ I hear a question and I go, “Oh, well. Yeah, that answer sounds a little silly.

“If you ever saw the movie Bull Durham, where the grizzled old veteran is trying to teach the young kid how to give baseball answers. And he just fills his head with cliches, like, ‘Well, it’s a game of inches,’ stuff like that. And those are baseball cliches. And some of the stuff that Creedence answers in that film, sounded like rock ’n’ roll cliches to me.”

You have a pretty impressive collection of guitars. What’s your favorite at the moment?

“I have a European-made Les Paul [-style guitar] that I got a few years ago, before Gibson sort of turned around, got their act together. It’s one of the most wonderful Les Pauls I’ve ever played. Recently, I was trying very hard to get a whammy on a Les Paul and be able to do all the stuff like I was doing back in 1969 or so, when I put a whammy on one of my Les Pauls.”

You’ve played a lot lately with your sons, whether as part of your show or having their band, Hearty Har, open for you. What have you enjoyed most about playing with them?

“First of all, every parent loves to interact with their children. You start that from the day they’re born. Having my sons grow up loving music and being musical was a true joy for me and my wife Julie. To be able to be on stage with the kids now as really great musicians, it’s a dream for me. I get a big kick out of playing the songs I’ve written, like Proud Mary and Bad Moon Rising, with my kids. Because we share DNA, there’s certainly a special understanding of how the music should go.

“As any parent will tell you, you love watching your children learn and become better at the things they find joy in. I love watching them play with Hearty Har. To be watching them with their band, and then have this film from me and my band from 50 years ago when I was roughly the same age as they are now, it’s a special way of looking at everything.

“It’s kind of surreal knowing I was on stage at that age with my bandmates, including my brother Tom. Being in a band with my brother was a wonderful thing; the whole thing felt like family to me. It was two guys whom I had gone to school with since eighth grade – and my brother Tom.

“At the time Royal Albert Hall was filmed, it was probably the absolute height of Creedence. It was all positive, it was all wonderful. It was almost pure, like a new snowflake falling from the sky. It was a wonderful feeling. The Beatles – whom we had all grown up with – had broken up just days before, so the entire music industry was shocked. My brother Tom had walked into a hotel room where I was giving an interview and broke the news he had heard on the radio.”

What’s next for you? How is the new material sounding, especially guitar-wise?

“I’m very excited to be making new music, especially now that I seem to have found the core of a great recording band. Artists of any kind go through some interesting times, sometimes strange times. If they’ve already created some works that are worthy, sometimes they find themselves in another part of their lives with a blank page, which is where I’m at today.

“I practice guitar ferociously. I’m grateful God allowed me to keep going with my love of guitar. It didn’t end when I was 15, and it didn’t end when I became famous. I love being able to see my own progress on the instrument I love. Hopefully, that mindset will be heard throughout the new music I will be making.”

- At the Royal Albert Hall is out now via Craft Recordings.

Josh is a freelance journalist who has spent the past dozen or so years interviewing musicians for a variety of publications, including Guitar World, GRAMMY.com, SPIN, Chicago Sun-Times, MTV News, Rolling Stone and American Songwriter. He credits his father for getting him into music. He's been interested in discovering new bands ever since his father gave him a list of artists to look into. A favorite story his father told him is when he skipped a high school track meet to see Jimi Hendrix in concert. For his part, seeing one of his favorite guitarists – Mike Campbell – feet away from him during a Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers concert is a special moment he’ll always cherish.