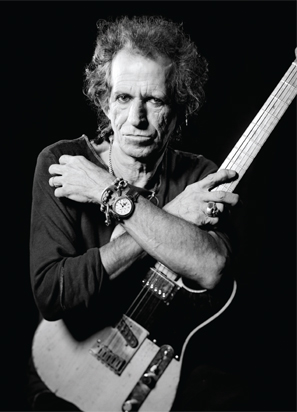

Keith Richards: Back with a Band

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Originally printed in Guitar World, November 2005

After drugs and illness nearly destroyed the world’s greatest rock and roll band, Keith Richards tells how he and the Rolling Stones survived and got back to their roots for their new hard-rocking album, A Bigger Bang.

Keith Richards is no stranger to crisis. Drug busts, murder, mayhem, rehabs and revolutions—rock and roll’s wizened pirate has weathered all with style and grace. His boozy swagger and toxic panache have become the stuff of pop culture mythology. Chaos is his métier.

But while Keef rides above the world’s fray, life of late has dealt his bandmates a few hard knocks and nasty shocks. As work got underway on the Rolling Stones’ newest album, A Bigger Bang, guitarist Ronnie Wood was mired in the depths of drug dysfunctionality—a severe crack addiction, according to some rumors. And Charlie Watts, the Rolling Stones’ mighty heartbeat since 1963, was diagnosed with throat cancer, undergoing surgery that was ultimately successful but put the drummer out of commission for a while.

“It was a reality check,” Richards says of potentially losing Wood and Watts. He gives a slightly uneasy laugh. “Mick [Jagger] and I eyeballed one another and said, ‘Jesus, no buffers. It’s just you and me, pal.’ Throughout the past year, I’ve felt that Mick and I were working more closely than we have in a long while. And I think it has something to do with what Charlie went through.”

Watts’ illness achieved what no amount of money, pleading or cajoling had been able to accomplish for years: Jagger and Richards finally put aside their long-standing squabbles and really started making music together again. As a result, A Bigger Bang is easily the best Rolling Stones album in a couple of decades: a classic cocktail of leering, three-chord rockers, epic ballads and lusty, low-slung blues.

“Yeah, it sounds pretty good, doesn’t it?” Keef allows.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Richards has always said that the Rolling Stones are Charlie’s band. Yet, at the dawn of the Sixties, before Watts or any other Stones arrived on the scene, there was Mick and Keef: two awkward teenagers holed up in suburban London bedrooms, dissecting American blues and R&B records like monks studying holy scripture, and taking their first tentative stabs at creating music. A Bigger Bang is shot through with reflections and echoes of the old Jagger/Richards magic.

“Mick’s on bass, harp, piano and guitar,” says Richards. “I’m on everything except the harp. It was a good feeling.” And while Watts and Wood were eventually able to rejoin the fold, along with key Stones supporting players Darryl Jones (bass) and Chuck Leavell (piano), A Bigger Bang remains a raw, back-to-basics rock and roll album: no horns, no violins, no Latin percussion sections or backup singers, just a coterie of core players dancing around the fire of tunes that rank among Jagger/Richards’ finest. Which is saying something, considering that the duo have written many of the most important rock songs of four decades: “Satisfaction,” “Jumping Jack Flash,” “Sympathy for the Devil,” “Gimme Shelter,” “Beast of Burden” and “Start Me Up,” to name just a few. The new material also promises to energize the Stones’ marathon Bigger Bang tour, which will detonate in the wake of the album’s release.

“The band is really getting into these songs,” says Richards. “I think maybe because we did start this album off in such a ‘Me and Mick’ area, the stuff is eminently playable onstage. Everybody’s really up for it. The 40 Licks tour [2002–2003] was basically retro, the old hits. But now we all feel like, ‘Yeah, let’s get our teeth into something new.’ ”

Much of the Rolling Stones’ best music has been born in the crossfire hurricane of things falling apart: bandmates becoming comatose or going AWOL, police knocking at the door, someone’s girlfriend overdosing in the toilet—but the calm eye at the center of that storm has always been Keith Richards, stoned out of his brain yet mystically lucid, unsteady of gait yet unwavering on the path of true rock and roll. These days, the Keef myth is in danger of overshadowing the man and his music, particularly since Johnny Depp brilliantly appropriated those legendary lurching mannerisms in his portrayal of Captain Jack Sparrow in Disney’s hit film Pirates of the Caribbean.

But the real Keith Richards is the one whose guitar playing charted the course of rock music through several of its greatest eras. Every note the man plays is deeply rooted in blues tradition, yet transmuted into something fiercely original, possessed of uncanny rhythmic savvy and enough grit to sand Mt. Everest flat. If you really wanna swagger, study that.

GUITAR WORLD The editors and readers of Guitar World recently decided that you are the most dangerous man in rock.

KEITH RICHARDS [laughs] I’m glad to say I agree with them. Bless their hearts.

GW How did you feel when you first saw Johnny Depp’s characterization of you in Pirates of the Caribbean?

RICHARDS Well, Johnny called me up before the movie came out, ’cause I think he was doing the PR for it. And he said, “Before you see it, you should know…okay, I admit it. I copied you.” He was in front of the game with me. I’ve known Johnny for a few years. Basically, he’s a friend of my son, Marlon, and I met him that way. He has a lovely guitar collection, by the way. He’s got stuff from the 17th, 18th century. First guitar or something. Amazing stuff. He’s a player.

GW Have you done the sequel yet, where you play his father?

RICHARDS I think they’re shooting it now. I can’t really say that much about it. I will tell you that Johnny and I were in L.A. two weeks ago totally dressed up as pirates. So there’s a hint. But at the same time, I don’t know about the ins and outs of scheduling and whether it will actually happen. Jesus, I never worked for Disney before. I never expected to. Mickey Mouse?

GW Talk about strange bedfellows.

RICHARDS So it’s not signed, sealed and delivered. But it is kind of in the air.

GW To what extent is that swaggering character the real Keith Richards?

RICHARDS It depends on what time of day you catch me. It doesn’t swagger so much in the morning.

GW Why were you interested in doing the film?

RICHARDS Shit, I’ll do anything. How difficult is it for me to play a pirate? Just stick a hat on me and a beard. Put on an eye patch and we’re away. Arrrgh! But it’s not necessary to wear all that stuff to be a pirate. Most pirates these days wear suits.

GW Acting has always been more Mick’s department.

RICHARDS You’re probably right.

GW So when Mick and you got together to start work on A Bigger Bang, there was no concerted plan to go back to basics or to strip down, the way the Stones did on Beggars Banquet, for instance?

RICHARDS No. We were kind of strapped for manpower, to tell the truth. Mick and I started putting this together last June. And at that same time we’d just gotten the news that Charlie was diagnosed with throat cancer. Mick and I were looking at each other going, “Well pal, this is it. Okay, you’re on drums and I’ll double on bass.” Thank God it didn’t come to that. But we did start off that way.

GW How many tracks was Charlie able to play on? Just some?

RICHARDS On no, he’s on all of them. But we started off working songs out with Mick on drums. And Mick’s a pretty good drummer, you know? He’s got a wicked backbeat, and luckily he doesn’t have a lot of flash, so he just sticks to the beat. We worked up the songs that way. Then Charlie came back and we were able to say, “Okay, Charlie, it goes like this.” And he came back like a ball of fire. Amazing. I guess he wanted to prove that he was still alive and kicking.

GW If the day ever came—God forbid—that Charlie Watts couldn’t make it, would the Stones go on?

RICHARDS That’s a good ’un. Probably not. As you say, God forbid. But at the same time, Mick and I kind of got over that hurdle this time, and said, “Well, we could still make records...”

GW What was Ronnie’s participation like on this album?

RICHARDS He’s on just about every track. There are a few tracks that Mick and I basically did together with just Charlie, but that’s not unusual.

GW We’ve heard all kinds of things about Ronnie of late—drug problems, he might not make the tour…

RICHARDS Oh no, he’s okay now. I think he fell in love with rehab. Ronnie…I’ve known him as stoned out of his brain as you can imagine a man can get. And I’ve known him straight sober. And quite honestly, there’s very little difference. Although I must say there’s a bit more focus on him now. Ronnie, unlike me, tends to overdo a thing. Me, I just do it. But right now he’s okay. I think

being straight will suit him...for a while.

GW The new song “Oh No, Not You Again!” is such a quintessential Stones three-chord rocker. Can you and Mick roll out of bed and write one of those in five minutes by this point? Or do they come a little less easily than that?

RICHARDS Sometimes there’s just a general idea—just the phrase “Oh no, not you again.” We sleep on that and the next day slip each other bits of paper saying, “How about if it went this way?” It’s all a bit of a patchwork really. But eventually you start to get the threads of songs. You knock off a couple of chords and say, “That’s nice.” Then you see what happens next. I feel it doesn’t have much to do with me. I’m just being led by a series of notes and possibilities. I just hang on and see what happens.

GW “Take Me Down Slow” has such a nice chorus melody. It’s a tiny bit like “Out of Time.” Classic Stones. Is that style of melody more Mick’s thing or more yours?

RICHARDS That’s hard to say. Mick came up with the basic song but I came up with the chimes [sings descending major chorus melody]. But I’d say that one’s more Mick than me, absolutely. You can tell. The ones I laid on him were “Rough Justice,” “Infamy,” and “The Place Is Empty.” So it’s kind of half and half. Mick comes in far more prepared than I do. I like to come in with the bare bones of an idea and see how it builds. Mick prefers to come in pretty much knowing how it’s supposed to go…or thinking he knows. Ha! Mick’s like that. He has to wake up in the morning knowing that he’s got to do something. Me, I just wanna wake up.

GW You’re like a Zen monk—always in the moment.

RICHARDS Yeah, I don’t plan ahead like Mick, but I can pick up on little nuances and ideas and incorporate them as we go along. I like to let things change. I don’t like to put things in a cage.

GW There’s also a very nice guitar solo on “Take Me Down Slow”— those Steve Cropper–esque major thirds. I’m assuming it’s you.

RICHARDS Yes, it is. Thanks. I’ve actually been enjoying playing guitar very much. I kind of stopped playing awhile after the last tour. I did a few sessions with Willie Nelson and a couple of other tracks here and there. But sometimes after a tour you say, “Jesus, I’ve played enough. I can’t think of another note.” So you kind of lay back. But that’s always a good thing, because when I do pick up the guitar again, after a few weeks or months, it’s always like, “Oh, yeah! Hello, pal, I missed you.”It’s always a pleasure to re-meet.

GW If you were going to be exiled to some desert island or distant planet for the rest of your life, and you could only take one of your many guitars with you, which one would it be?

RICHARDS It’s only right I take my ’31 Martin 00045 acoustic. That’s been my number-one acoustic for the past 10 years or so. And you never know when you’re gonna see electricity again. There’s no point singing for your supper on a Stratocaster without a goddamn amp.

GW “Back of My Hand” is a great blues. What’s the story behind that one?

RICHARDS Mick came up with that. He started to play it one day on acoustic guitar and I started thinking, “prison songs...” We were just casting ideas about. To me, it’s a classic sort of Muddy Waters thing, or even earlier. And as we were getting it going, I went, “Jesus Christ, we could have cut this at Chess [Records], baby.” You are what you listen to, in a way, and I never stopped listening to the blues. Even if I go off on other tangents, there’s always that basic diet, thank God.

GW After all these years of being deeply into the blues, how has your perception of the blues changed and evolved?

RICHARDS That’s a good ’un. It does change as you grow up. It’s a ludicrous idea for a 17- or 18-year-old white kid from London to go around saying he’s a blues player, which is what I used to do. You have to go through a bit of life, I think, in order to play the blues for real. That’s why most blues players are not that young; you gotta be able to have a few stories to tell, ’cause it’s a very strict format, the blues. It’s 12 bars and three chords. You can throw in a few extra ones, but it’s so amazingly malleable as a form of music that you could never learn it all. There are so many different ways you can angle it. It’s almost like passing along information. It’s fascinating—there’s so much music out there. You can go classical and jazz and I love all that, too, but I’m still finding out how to work my way through those 12 bars.

GW On “The Place Is Empty,” you do your Hoagie Carmichael/Cole Porter suave ballad thing, in much the same vein as [Carmichael’s] “The Nearness of You.” A lot of people are surprised that you have those kinds of influences.

RICHARDS Well, I like to surprise people.

GW When did you develop a taste for that kind of thing?

RICHARDS Hey, I grew up with it, man! My mother played me jazz and all the standards. That stuff just drips off of me. My mother played me Sarah Vaughan, Billy Eckstine, Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Count Basie… It’s just that rock and roll suddenly came along and totally diverted my attention.

GW You play piano on that track, which is something you’ve done on the occasional Stones record, going back to the “Let’s Spend the Night Together”/“Ruby Tuesday” period, I guess.

RICHARDS Yeah, I was in pretty early. It was [Stones pianist/tour manager] Ian Stewart that got me into it. I never thought of playing piano at first. My attitude was “I’m the guitar player and that’s it.” But sometimes I’d catch Ian Stewart playing some really beautiful blues piano all by himself. One day I just said to him, “Hey Stu, show me how to do that. I gotta know.” And I went on from there. I enjoy the piano because at least it’s all laid out in front of you. With the guitar, you gotta keep peering around the neck. You don’t have to wear the piano either. And you can sit down. There’s room for an ashtray and a drink. A civilized instrument.

GW What was the very first Rolling Stones album that was conceived as an album and not simply as a willy-nilly selection of tracks?

RICHARDS In actual fact, surprisingly enough, that was the first one [1964’s The Rolling Stones, released in the U.S. as England’s Newest Hit Makers]. We only had about one or two singles out before we made it, so we were making that as an album from day one. Probably because of the Beatles, albums were just becoming the potential medium of choice at that time. Singles were always like gasping for air, ’cause you needed a new one every eight weeks. “Satisfaction” goes to Number One all over the world, and the very moment you’re saying “Let’s have a drink on that,” there’s a knock on the door: “Where’s the follow-up?” It was a good school for songwriting, but I’m quite glad that it eventually became less of an important thing to have a hit single every few weeks and your life depended on it. We got to nurture a few albums. We got to overnurture a few actually. “How long did that take to make?” “Two years. I can’t actually tell you where the time went, but...”

GW I remember [former Stones producer] Glynn Johns complaining to me about that.

RICHARDS Oh, Glynn’s a famous complainer.

GW But certainly by the time you get to Beggar’s Banquet, the model is in place for the classic Stones album experience—a few tough rockers, a blues, a ballad or two, maybe a country number…a whole musical trip that takes you over hills and valleys.

RICHARDS A lot of that was us evolving with the technology. We started on two-track and within a year it went to four. Then it went to eight, 16, 24… And everybody was dickering around trying to figure out how to use these concepts and inventions. The machines were coming in with “Missiles Fire” written on them. And that was the record button!

GW So what’s exciting about making records with today’s technology?

RICHARDS You can make a record anywhere now. The studio isn’t so important. In fact, we don’t use studios. We just find a good room that’s handy for everyone to get to. Most of this album was done at Mick’s house in France. The machinery was inside the room with us. The producer, Don Was, and the engineer—they were in the room with us. So you get rid of that glass barrier between the studio and control room, which can be enormous at times. I know from all those years of working in huge studios. You do your thing in the studio, then you go into the control room for a playback and you’re on another planet. They’re not gettin’ it in

there! So it’s much better to do it with the recorders actually in the room, and you can do that these days. The equipment is smaller. You can separate things easier without having to put big booths around them. We just played in a small room for most of this album. No doubt for a symphonic orchestra, there’s something to be said for a big studio. But I’ve found with rock and roll that you’re always playing on someone else’s turf. They’ve never built a room for it yet. You have to beg and borrow: Can I use your football stadium? Can I use your auditorium?

GW But you’ve achieved some pretty epic results working out of Mick’s house. “Streets of Love” is a classic Stones ballad, very much in the tradition of “Wild Horses,” “Angie”…

RICHARDS Yeah it kind of is. It’s a Mick tour de force, in a way. But we all really enjoyed playing it. When we first knocked it out on acoustic, we felt, Oh, that’s nice, but it sounded kind of standard. So then Mick and I were saying, “It’s the dynamics that count. You gotta take it up and down.”

GW You’ve always had a real knack for layering guitars onto ballads. It starts on acoustic. A bit of electric comes in…

RICHARDS Yeah, it’s almost like one guitar part suggests another one, hopefully without overdoing it. On some of the earlier albums, I was overdub crazy. I would have eight guitar tracks, but I only used three or four at a time. I’d take one out for a section and bring another in. In a way, it’s the same thing now. I just don’t overlayer tracks as much.

GW There’s something about Mick’s performance on “Streets of Love.” Maybe you can shed some light on this for me. It’s so stylized, so mannered.

RICHARDS Yeah, I know. Isn’t it?

GW Yet there are moments when he’s really throwin’ down. Does that dichotomy still surprise you after all these years?

RICHARDS It can, yeah. Mick sometimes goes into “a mode,” and you’re like, “Is that you? Are you trying to be somebody else?” Sometimes you have to figure that out. Yes, it is manneristic at times, but other times he’s so fucking loose and cool, like on “Rough Justice.” And his harp playing blew me away all year. He’s Louis Armstrong on that. Also his guitar playing is a lot better. He did a lot of rhythm guitar on this album. There’s a lot of three-guitar stuff there—Ronnie, Mick and me. That’s been interesting. Mick is a lot more proficient on guitar now. If he wants to play, I say, “Play!” I’d never be the guy to say, “Stop it. Forget about it.”

GW Yet I’ve asked you about this in the past and you’ve always said, “Mick’s okay on acoustic, but keep him away from electric.”

RICHARDS Exactly. But he’s finally really starting to get the electric stuff down. Realizing that it’s a different instrument than acoustic, especially if you want to use effects and stuff like that.

GW So, after some 40 years…

RICHARDS Yeah, it takes a while. We’re slow learners.

GW There’s a track called “Neocon” that didn’t make it to the album, or might not?

RICHARDS I’m not sure if it’s on there or not. I’m still getting bits of paper saying, “Here’s the final lineup,” and every day it’s slightly different. It might be on there. I can’t really confirm that. It’s quite a groove of a track, though.

GW I hear it’s real political.

RICHARDS In a way it is, yeah. There are all these neoconservatives now. I suppose it depends on who you’re pointing the finger at. Personally, I prefer to keep politics out of music. But at the same time, if it’s done the right way, I don’t rule any subject out.

GW What’s your take on what’s happening politically right now, in America and the world?

RICHARDS I don’t know, man. I roll with the punches, and I think everybody else will. Things have changed. There’s a lot of things in the air, including bodies. And it’s not the way to get along, is it? And something has to be done. Personally, I’d have a suicide bombers’ convention and they can all blow each other up.

GW As you said, the Stones have never been much of a political band. But tracks like “Gimme Shelter” and “Sympathy for the Devil” have definitely reflected turbulent times.

RICHARDS “Street Fighting Man” too, yeah. But they usually touch on the periphery. They’re more observations from an outside point of view than jumping right into the middle of the fray. I’ve always been a bit wary of that. And “Neocon” might be a bit like that, I don’t know. I’ve raised the subject with the lads and we’ll see how it flies.

GW “Salt of the Earth” [from Beggars Banquet] certainly showed your heart was in the right place.

RICHARDS It better be. There’s only one spot for it.

GW What is your memory of when the “Keith Richards elegantly wasted” characterization started to permeate popular culture?

RICHARDS That’s other people’s words, my dear. I just do it and you describe it.

GW But was there a point where you started to riff on that image deliberately?

RICHARDS No, I never thought of that. I’m just doing what I do, man. You know? I’ve always had the opportunity to do it. And I never really thought it was anything unusual. It was only when I woke up the next day and read about it in the paper that I realized someone wanted to make a big deal out of it.