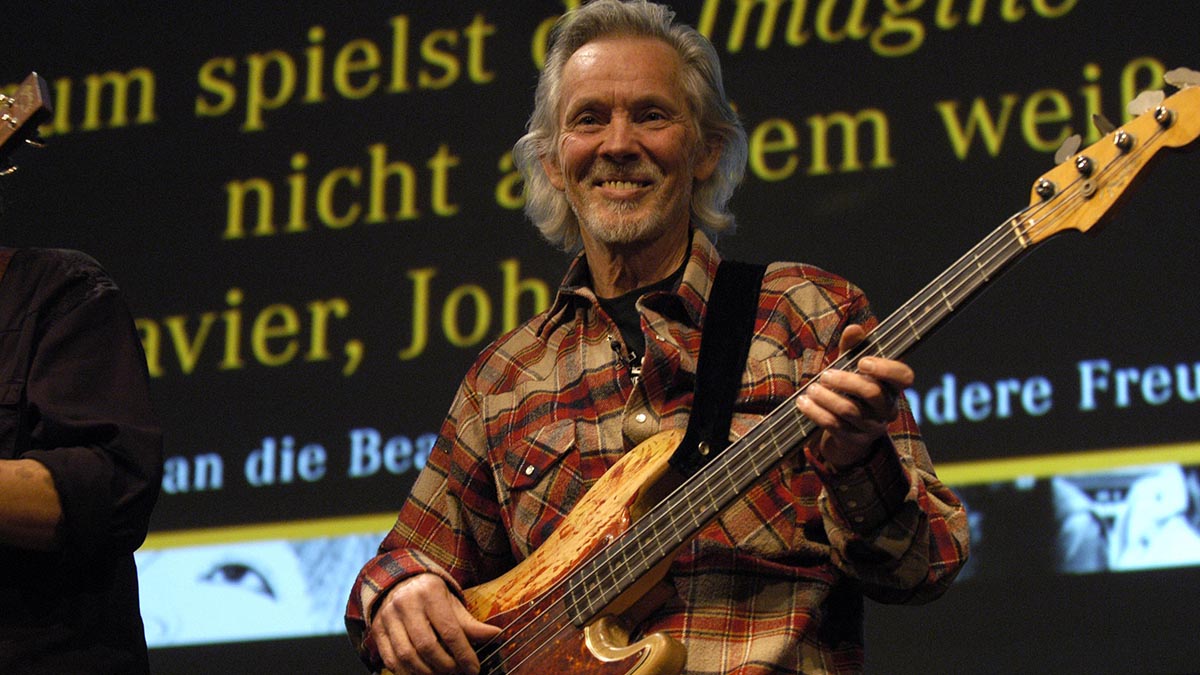

Klaus Voormann: “John Lennon gave me all the freedom in the world... The Plastic Ono Band lineup of Ringo, John and me is my favorite of all time”

How many bass players have shared the stage with the Beatles, both as a band and individually? Only one...

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Klaus Voormann, born in 1938 in Berlin, first heard rock ’n’ roll being thrashed out in a club in Hamburg by a five-piece group of Liverpudlians known as the Beatles.

Voormann briefly played bass with the Fab Four while their original bassist Stuart Sutcliffe took a break, and went on to join John, Paul, George, and Ringo on a variety of post-Beatles projects – including Lennon’s Plastic Ono Band and Harrison’s All Things Must Pass albums, both recorded in 1970.

By then, Voormann had enjoyed a stint with Manfred Mann between 1966 and ’69, and become a sought-after session bassist. His distinctive playing can also be heard on the intro of Carly Simon’s You’re So Vain (1971) and on Harry Nilsson’s definitive cover of Badfinger’s Without You (’72). Notably, he appeared on Lou Reed’s 1972 album Transformer, produced by David Bowie and Mick Ronson.

Beyond the bass, Klaus has enjoyed a separate career as an artist, designing album sleeves for acts as diverse as the Bee Gees, Wet Wet Wet, and the Scorpions. His best-known cover, the Beatles’ Revolver, earned him a Grammy award in 1966. That’s quite a resumé, as we agreed when we met the 83-year-old recently.

What is your preferred recording setup, Klaus?

“I used a Fender Precision and an Ampeg with a 15-inch speaker. I always played that bass with flatwound strings – and they were old, I never changed them. I didn’t always use the amp – I would plug straight into the board.”

Tell us about your influences.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“I was always listening to jazz, because I like the double bass. It’s interesting – my main influence was James Jamerson, who recorded a lot of Motown. He was a double bass player who got into electric playing.

“He did the same thing that I did – he held a sponge under the strings. I didn’t know he did it, but it muffled the tone on the sound of those Motown records. It was magic to me, what he did.”

Your relationship with the Beatles began in Hamburg at the start of the '60s.

“Yes, it started there. We sat there for a while as spectators, listening, looking and having fun with a drink and dance. Bit by bit we all wanted to connect, and among our group, I was asked to go up and talk to them. I met John and he introduced me to Stuart Sutcliffe, and from then on it was like a world on fire. It was about art, movies, and music.

“They were so open – and it was difficult for us, being German, to understand. They would easily talk about their inner feelings; they weren’t scared of opening up. When they did that, they opened us up and showed us how people can be. Germans in general are very scared to open up their inner life. We were taking purple hearts [amphetamines] and talking so much... It was unbelievable.”

You are also one of the few people to have played with them live.

“Yes. Stuart handed me his Hofner President bass, and went off for a cuddle with Astrid Kirchherr [photographer]. I played it with my back to the audience. It was the early hours of the morning with a few couples dancing and one or two sleeping at the bar – it was a real night atmosphere. It was the first time in my life I had a bass in my hand.”

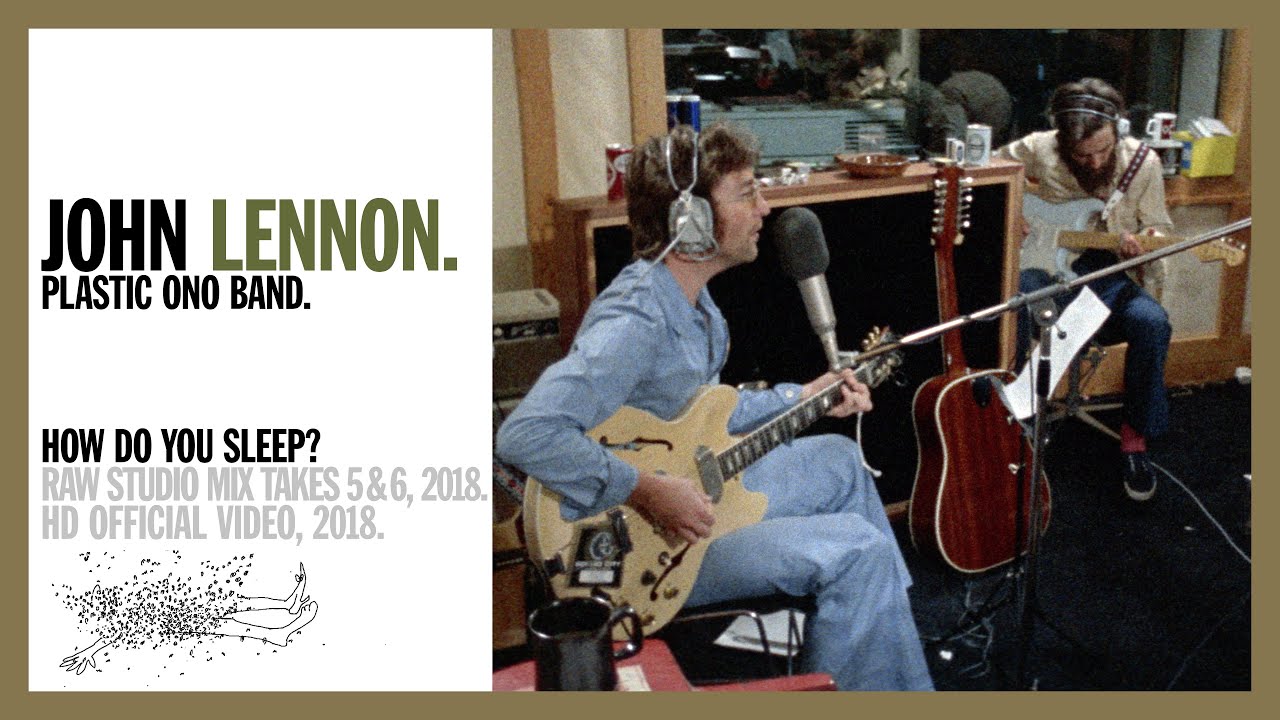

You’ve worked with the Plastic Ono Band for many years, on and off. Is it true that the early-'70s sessions were difficult for Ringo Starr, because John Lennon had become a different person through primal scream therapy?

“Yes, Ringo was a little upset at first. John and Yoko were so engaged with one another, that it wasn’t the same type of work he did in the Beatles. It was just John and Yoko, and they were so together that Ringo was a little sad. Later, John said to him, ‘It’s not just me any more – it’s Yoko and me. We are together, and it’s different.’

“Ringo hadn’t known a relationship the way John and Yoko were: he would be more used to a more macho relationship [with Lennon]. When [Lennon] met Yoko, that was the real John. Back in Hamburg, he was a cocky rocker. John was always frustrated until around Sgt Pepper, and after that, he met Yoko, and he was departing.”

The Plastic Ono Band albums of 1970 were recorded just months after the Beatles’ split was announced.

“Yes, Paul made it public with the announcement but [the split] was clear long before – this was not new to John. His frustration was over, he was relieved. He was free now. John still had some obligations, but he was completely free. He saw it as fact. I don’t think he was angry about it.”

How much freedom did you have when recording bass with John?

“John gave me all the freedom in the world. He never told me what to play.”

You continued to work with John throughout his solo career, as well as recording with George and Ringo.

“It was like a snowball effect. Once I played for John, I was asked by George, and I couldn’t have been happier. Then it was Carly Simon and Lou Reed – it was such a nice selection of people that asked me to play. All the people I played for I had fun with, and was happy about the fact they asked me.”

How did your experience in the studio differ between each Beatle?

“George would come into the studio with little joss sticks: he would light a candle and dim the lights – it was like a little altar. He would take much more time to record. The Beatles were never mentioned: it was time to turn the page and move on.

“Ringo would always need someone to help him play the chords. He would rely on friends. He was different in that I think he would have played with the Beatles until the end of his life.

“John would rely on Yoko. She was a great catalyst for him most of the time: even with just a few words she said the right thing, and that wasn’t easy to do.”

Tell us about working on Transformer with Lou Reed, David Bowie and Mick Ronson.

“Lou Reed was fantastic, and such a lovely person. He was great long before this album, he was underrated. This project with Bowie and Mick Ronson was a well-done record, and Lou had such great songs. Walk On The Wild Side is not me playing bass [it was Herbie Flowers – Ed] but I loved it.

“He and Bowie got on well: They were always laughing and having fun. It was a strange atmosphere in a great way, you know – they were writing about pimps, transvestites…"

You also recorded All Things Must Pass with George in 1970.

“I love All Things Must Pass. With the title track and Isn’t It A Pity, there is a sense of looking into the past but also the future. A lot of people say it’s sad, but George believed that his body was not important; it was a shell for the soul. That’s difficult for people to understand. It sounds very sad – but it’s not really: he was very happy about his life.”

- Klaus Voormann's art is available through his official webstore.