Dhani Harrison on the incredible story of his father George's All Things Must Pass album

“You need a rhythm guitar player and you get Eric Clapton. How amazing is that?”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

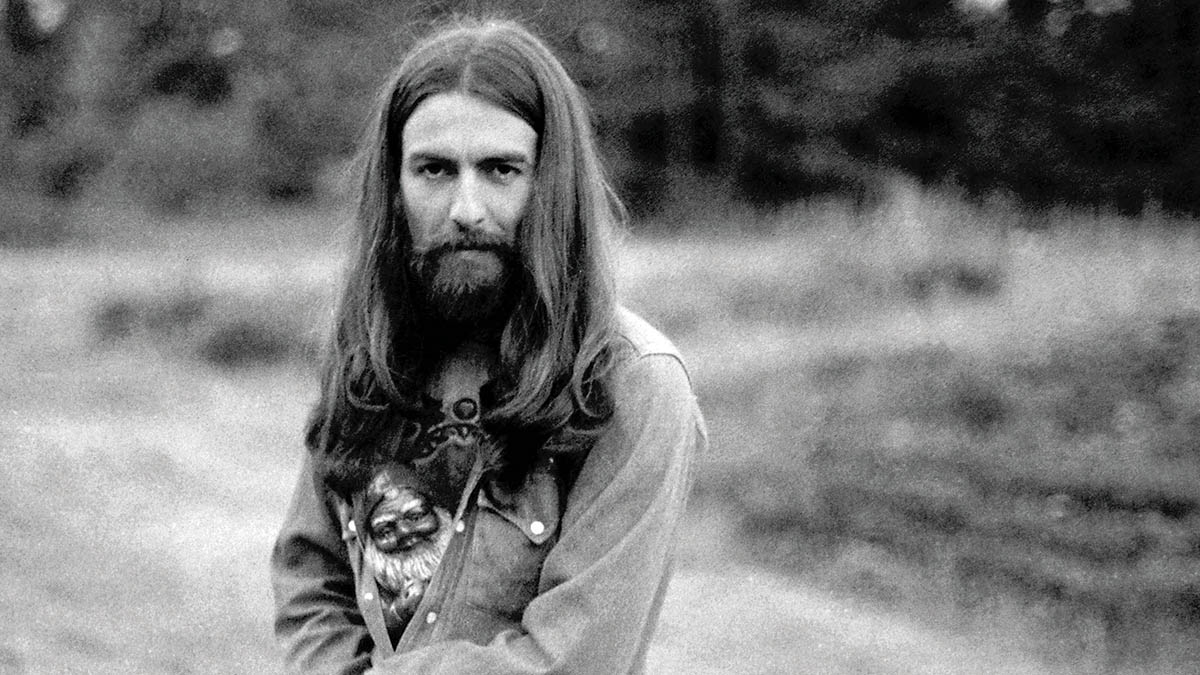

All Things Must Pass is the War and Peace of rock and roll. It’s a lot to wade through, but the wade is well worth it. Like Tolstoy’s great novel, George Harrison’s massive 1970 triple album is an epic, monumental, somewhat daunting masterwork.

It captures the irrevocable march of time (the passing of the Beatles and the swinging '60s) with a profound sense of loss, resignation, renewal and an all-encompassing spiritual perspective based on universal love.

While it wasn’t the very first rock triple album — the Woodstock soundtrack album came out six months earlier – All Things Must Pass was the first triple-disc rock studio album by a single artist, and an ex-Beatle at that.

It would yield the first Number One hit by an ex-Beatle, the wistfully expansive My Sweet Lord, and now-iconic Harrison songs like What Is Life, Isn’t It a Pity, Wah-Wah and Beware of Darkness.

All Things Must Pass also served as a gateway to the large-scale, “more is more” aesthetic of '70s classic rock, and the emergence of Harrison from under the giant songwriting shadow of John Lennon and Paul McCartney. He would prove to be one of the most compelling and original voices of the entire rock era.

The first Beatle to venture into solo recordings, Harrison had already released two previous instrumental albums on his own prior to All Things Must Pass – the Wonderwall Music film soundtrack (1968) and Electronic Sound (1969), one of the earliest albums to feature the legendary first iteration of the Moog modular synthesizer.

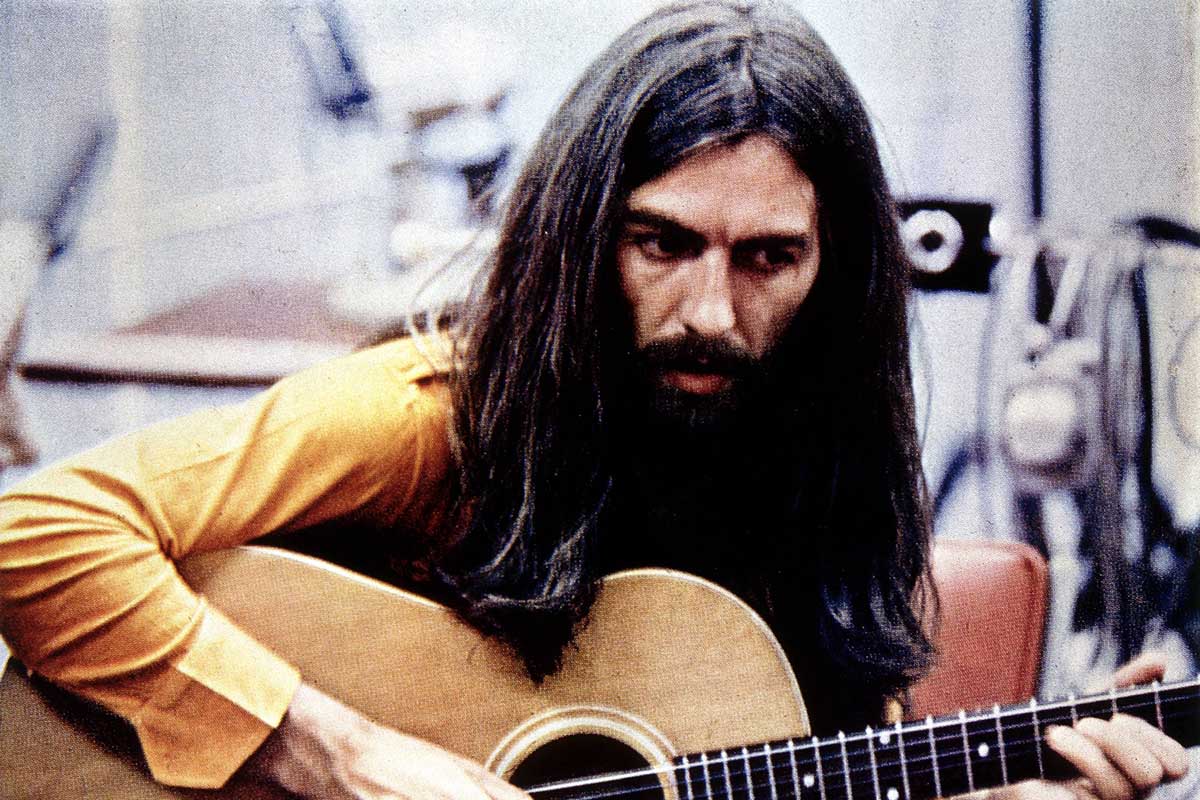

But George’s mind and heart were once again rooted in guitar-driven rock and roll as he flung wide the doors of EMI’s Abbey Road studio to welcome an all-star conclave of players that included Eric Clapton, Ringo Starr, Klaus Voormann, Billy Preston, sax player Bobby Keys, and country pedal steel ace Pete Drake. Among its other distinctions, All Things Must Pass is one of rock’s great guitar albums.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“You need a rhythm guitar player and you get Eric Clapton. How amazing is that?” On a Zoom call from the English countryside, where he’s been marooned by the pandemic, Dhani Harrison, George’s son, has spent the past five years of his life executive-producing the 50th Anniversary Edition of All Things Must Pass. Yet, after all that work, he still has the enthusiasm of a teenage fanboy as he marvels at the disc’s guitar treasures and transcendent songcraft.

“The backing band... it’s Derek and the Dominos, before they ever recorded any-thing on their own. It’s the first thing they ever recorded. They all got together before touring and before recording; they came into the studio to do All Things Must Pass. And that band is so hot. You listen to some of these tracks and you think, ‘God, it’s Derek and the Dominos!’ It’s a hell of a band.”

Poring over the box set’s pristine remix/remastering of All Things Must Pass, Dhani and his co-producer Paul Hicks had ample opportunity to dissect the album’s many standout guitar moments. One of the innovations All Things Must Pass introduced to the triple rock album format was the inclusion of a full vinyl jam disc.

All Things Must Pass is coming from a time in George’s life that is very dualistic. It’s very dark, yet some of it expresses some of the most exalted states of clarity you can have

“There were lots of points you’re, like, ‘Is that Clapton? Is that Dad?’” Dhani marvels. “You’re like, ‘Oh, it’s Clapton. Dad would never play that.’ But at that point they were synched up. So it’s Dad kind of playing Eric riffs and Eric playing these George riffs.“

While all this rip-roaring guitar bond-ing was going on in the studio, Harrison was in the process of losing his wife, Patti Boyd, to Clapton. Harrison had, of course, also just lost the band he’d played in since he was 14 – the band that had made him both rich and famous.

And while sessions for All Things Must Pass were underway, his mother died. The album is one of rock’s most poignant evocations of loss and sorrow. Harrison’s personal sense of bereavement at the time was echoed by the world all around him.

The '60s utopian dream of peace and equality was, as Harrison’s ex-bandmate John Lennon noted on his own debut solo album, “over.” Counterculture kids of the era, myself included, just had to find some way to carry on, as Lennon suggested in his song, “God.” But while Lennon announced that “God is a concept by which we measure our pain,” spirituality had provided Harrison with his own way of carrying on – a lifeline.

“All Things Must Pass is coming from a time in George’s life that is very dualistic,” Dhani notes. “It’s very dark, yet some of it expresses some of the most exalted states of clarity you can have. And somewhere in the middle is that whole experience and that whole record.”

When All Things Must Pass first hit the record shops in the wintery November of 1970, fans found that there was a lot to digest among the 23 tracks that comprised the original release.

Densely produced by George Harrison and infamous studio legend Phil Spector, the songs are awash in Harrison’s unique chordal modulations and spiritual concepts, drawn from Hindu tradition, that were not as familiar to many rock fans back then as they’ve become in our own time, with online meditation apps and yoga studios abounding in every city and town.

The 50th Anniversary reissue of All Things Must Pass is far more massive than the original. Along with the remix/remastering of the original album, created with the latest digital technology, there’s also a cornucopia of outtakes, previously unreleased tracks and lavishly printed liner notes and photos.

Well-heeled consumers can get an Uber Deluxe Edition, which comes in a wooden box packed with bonus items like a string of Rudraksha meditation beads and a bookmark made from a tree on Harrison’s Friar Park estate in England. There are also more manageable Deluxe and Limited editions offering the music on both vinyl and CD.

The abundance of material on All Things Must Pass is directly attributable to the large backlog of songs Harrison had amassed during his tenure with the Beatles. With Lennon and McCartney’s songwriting predominant, Harrison could usually get only one or two of his original compositions on each Beatles album. This increasingly became a sore point as the Beatles began to unravel at the end of the '60s.

Once they’d called it quits, all four band members promptly released solo albums. But while Lennon and McCartney both recorded spare, stripped-down debut solo discs – McCartney working largely on his own and Lennon with a small coterie of trusted musical comrades – Harrison went for a big production with a large and stellar cast of A-list players.

“Dad had obviously built up so many songs after the Beatles,” Dhani says. “They didn’t get their day in court, you know? So he went big. Paul and John had already had their big arrangements with things like A Day in the Life, I Am the Walrus and Penny Lane. I think Dad wanted that kind of treatment and attention for his own songs.”

Paul and John had already had their big arrangements with things like A Day in the Life, I Am the Walrus and Penny Lane. I think Dad wanted that kind of treatment and attention for his own songs

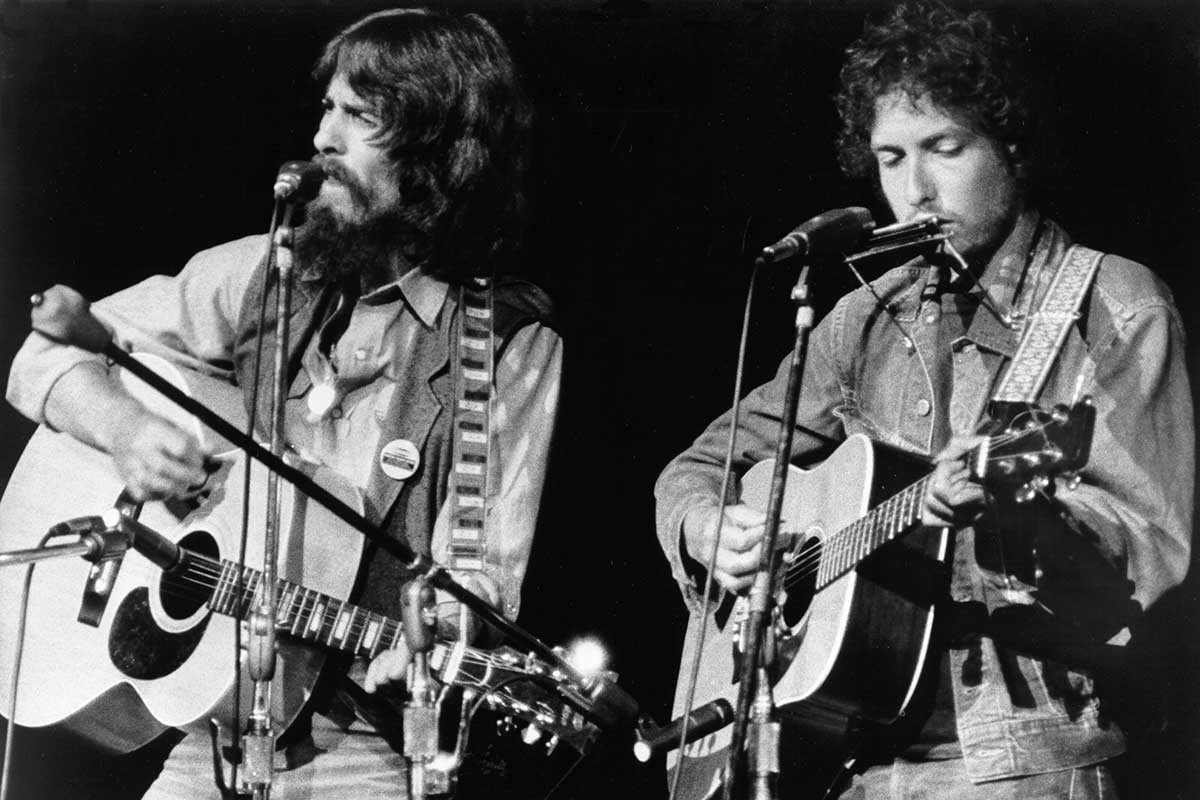

As the Beatles imploded, Harrison had taken to spending time with his friend Bob Dylan in upstate New York, where Dylan was working with members of the Band to craft his own post-'60s musical identity.

Coming from the tense, increasingly hostile atmosphere of Beatles sessions, Harrison was struck by the easygoing, ego-free camaraderie between Dylan and his fellow musicians.

All Things Must Pass would start off with a song, I’d Have You Anytime, that Harrison co-wrote with Dylan, and would also include a cover of Dylan’s own If Not for You. In working with the many great musicians who helped realize All Things Must Pass, George wanted to create the same kind of friendly, open-hearted spirit of collaboration that he’d observed in Dylan’s work with the Band.

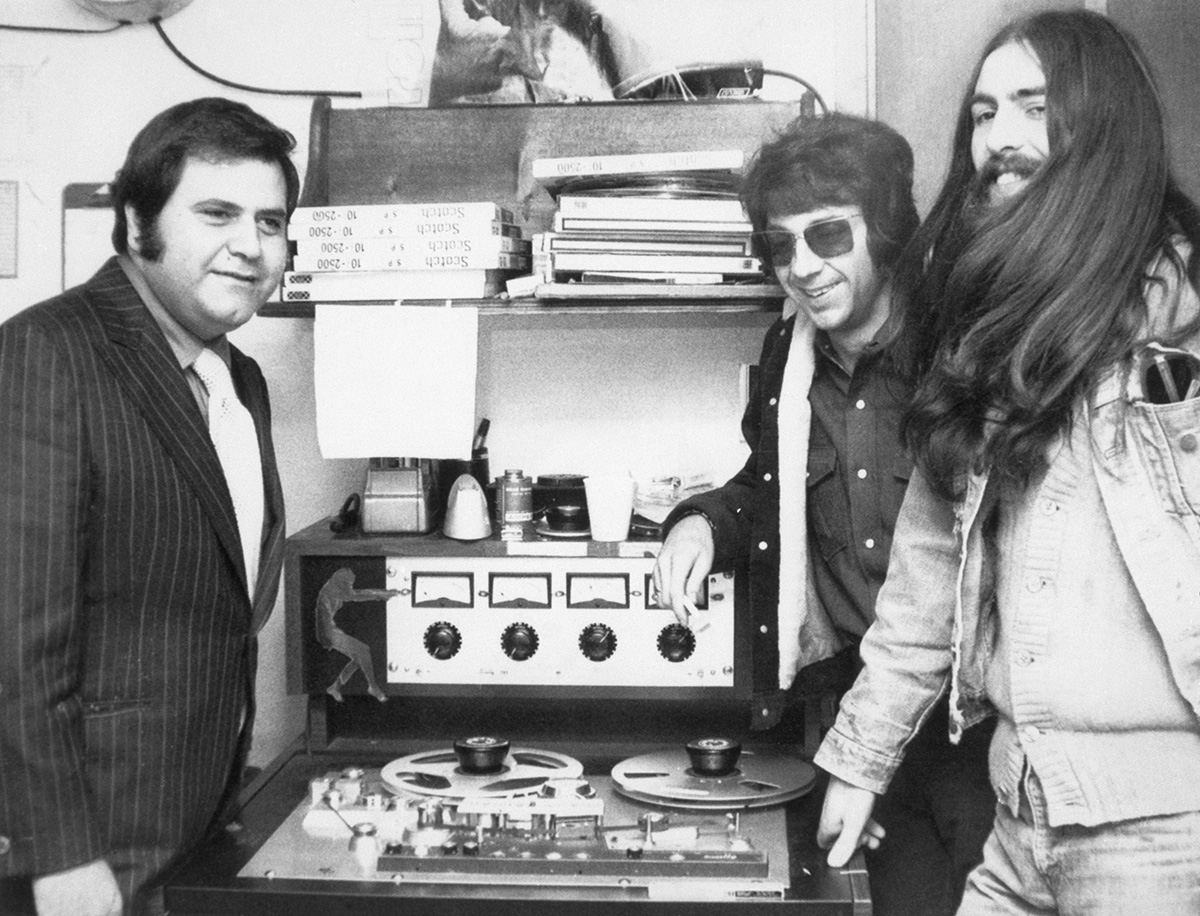

At the same time, though, he was work-ing with Phil Spector, who was noted for his epic productions – the “little teenage symphonies” that had revolutionized mid-'60s pop music via hits by the Ronettes, Crystals, Righteous Brothers and others.

In this context, All Things Must Pass can be characterized as “The Basement Tapes meet Spector’s Wall of Sound.” As the sessions unfolded, it was often Spector who kept calling for another guitarist, another piano player… which expanded the album’s “Who’s Who” of top '60s and '70s musicians to include guitarist Dave Mason (Traffic), keyboardists Gary Brooker (Procol Harum) and Gary Wright (Spooky Tooth) as well as Peter Frampton, members of Badfinger and more.

All of this was being assembled on eight-track tape, which was the prevailing multitrack technology at the time. In some instances, the eight tracks were mixed down to two tracks of a second eight-track reel, with overdubs added on the remain-ing six tracks.

And in a few other cases, the project moved from Abbey Road over to another legendary London studio, Olympic, which had recently taken delivery on one of the first 16-track machines. Spector’s production approach involved combining multiple instruments on a single tape track – which made remixing All Things Must Pass somewhat problematic.

“So many people have told us, ‘You gotta de-Spector the album,’ Dhani says. “I’ve been hearing that for the last 20 years – every time we do a reissue. But you can’t de-Spector it. The way it’s recorded, everything fits in its own place, with different instruments taking up different bandwidths.

“So if you want to, say, increase the volume on the piano, you’re not really using the volume knob. You’re more just using the frequencies to bring out an instrument more. That’s where you really see what Phil was doing. It takes a lot of understanding.”

Spector had been a bone of contention in the long painful process by which the Beatles unraveled. He had been brought in to do additional production and mixing on Let It Be by Allen Klein, the manager that Lennon, Harrison and Starr had chosen to represent the Beatles over the objections of Paul McCartney, who wanted to place the quartet’s business affairs in the hands of Eastman & Eastman, the firm run by his father-in-law and brother-in-law.

McCartney hated Spector’s work on Let It Be and, years later, would release his own “de-Spectored” version, Let It Be... Naked. But both Lennon and Harrison were pro-Spector and elected to work with him on their debut albums. Although Dhani Harrison suggests that his father might have gotten the short end of the stick.

“The stuff Spector did with John [on the Plastic Ono Band album] was fantastic. And I think when he did All Things Must Pass, he might have been a little bit more, as they say, off his head than when he was doing some of the other stuff. I know my dad had a very hard time working with Phil.

“He had a bad drug problem and he was, you know, a nutter. But, saying that, my dad was the guiding force. He was the one going and waking Phil up and saying, ‘Please,’ you know? He didn’t have to do a lot of the things he was doing to keep Phil up, like bringing him coffee and checking to see if he was still alive.

“Usually the producer has to do things like that for the artist. So I think working with Spector was a little trying. Dad didn’t go back into the studio for a long time after that. Let’s just say that.”

While Harrison was most likely not as dissatisfied with Spector’s work as McCartney had been, he was intent on remixing All Things Must Pass during the final years of his life. Along with Paul Hicks and mastering engineer Alex Wharton, Dhani worked with his father on the 2000 remix/reissue of All Things Must Pass. He sees the 50th Anniversary remixes and remastering as a continuation of that process.

He didn’t have to do a lot of the things he was doing to keep Phil up, like bringing him coffee and checking to see if he was still alive.

“Paul Hicks and my dad were very good friends. And Alex Wharton was a very good friend. He knew what we wanted from this. He knew where we had too much reverb, and he knew my dad hated having too much reverb on his vocals. He used to sit there with him every single day. He mastered all of my dad’s catalog.”

Dhani says that advances in digital audio editing technology in the two decades since 2000 made it possible to dig into those tracks containing multiple instruments and achieve a greater degree of isolation and separation of individual instruments. He regards the box set’s remixes and remasterings as a marked improvement.

“We played it to my mum and she cried. Paul Hicks played it to me and I cried. It was the opening track, I’d Have You Anytime. You could hear the fragility in the voice. It’s like a tarp has been lifted off the voice. It sounds so vulnerable, and yet so wonderful. I A/B-ed with the original a million times. The new mix has something that the original didn’t. I felt if a mix could move me like that, it’s definitely going in the right direction.”

You can’t really hear it in the full mix. But once you’ve heard some of the tracks soloed, you go, like, ‘Wow, that’s a big dirty Moog bass line in the middle of Isn’t It a Pity!

The process was filled with revelations – such as the extent to which Harrison employed his Moog modular synthesizer on All Things Must Pass. He owned the first Moog in England, and one of the earliest units Moog ever produced. It had played a role on the Beatles’ Abbey Road and Harrison’s Electronic Sound album. But Dhani and his colleagues discovered the instrument is all over All Things Must Pass as well.

“You can’t really hear it in the full mix. But once you’ve heard some of the tracks soloed, you go, like, ‘Wow, that’s a big dirty Moog bassline in the middle of Isn’t It a Pity! And this is why Phil is Phil. You can’t hear the Moog until you’ve heard it once. Then you can never unhear it.

“Once you’ve discovered this stuff, it’s like archeology. You can’t bury it back up. It has to change your perspective on things. And it only makes things better. At no point were we like, ‘Oh, I don’t like hearing all that stuff.’ It’s this big doubling act. It’s mad, and it’s way more electro than you’d think. You’d never guess that that those instruments were in that song.”

At the other end of the spectrum, the inclusion of a country pedal steel stalwart like Pete Drake demonstrates the eclectic expansiveness of Harrison’s musical vision. “I like to think of All Things Must Pass as the best country record of all time,” Dhani says. “That great Pete Drake pedal steel on Behind That Locked Door,’ the song my dad wrote about Dylan.... There’s a country hit if ever I’d heard one.”

The massive scope of the original album project and the stylistic breadth of the material Harrison stockpiled come across clearly in the box set’s generous selection of bonus tracks. George spent a day in the studio running down songs for Spector with just an acoustic guitar and vocal. These recordings offer an intimate glimpse of Harrison at his most Dylanesque.

The bonus tracks are where people are going to go, ‘Oh, this is what we would call de-Spectored’

There was also a day of full-band studio rehearsals, exploring options and locking arrangements into place. There’s quite a range of material there, from spiritual songs like Om Hari Om and Mother Divine to the country-flavored Going Down to Golder’s Green, which calls to mind the Chet Atkins-obsessed George Harrison of the early Beatles recordings.

“There’s a version of Run of the Mill that sounds like Jessica by the Allman Brothers,” Dhani adds. “It’s got all these great guitar harmonies. The bonus tracks are where people are going to go, ‘Oh, this is what we would call de-Spectored.’”

Dhani and his crew worked their way through hundreds of tape reels to curate a selection of tracks that provides intriguing insights into the evolution of All Things Must Pass without becoming tedious. There’s a “party disc” of studio banter, for example. But we’re not asked to suffer through take after take after take, to the point where we end up wondering if we can submit an invoice to the Harrison estate for all the hours spent.

“When we’re making boxsets, I’m very conscious of ‘I don’t want to hear 20 versions of All Things Must Pass in a row,’” Dhani says. “Like some of those Beach Boys box sets. I don’t want to hear 50 versions of God Only Knows. It’s better to have three versions. We’ve got more material. I mean I’ve got cassettes. And we decided not to put the cassette stuff up against the masters on this record, like some people do.

“At some point, years from now, there might be our version of the bootleg series. But we want to make sure everything is high quality. My dad was always very conscious of scraping the bottom of the barrel, you know. He’d say, ‘Well, if you make my new album you’ll have to call it Scraping the Barrel.’ It’s a real thing. People do scrape the barrel too much. We’re very conscious of not doing that. Everything released since my father has passed away has been of the highest quality. There are no throwaway things.”

A gifted songwriter, musician and film composer in his own right, Dhani Harrison certainly doesn’t need to repackage Harrison Senior’s old records to get by. In fact, he’s put a lot of his own creative work on hold in pursuit of what he sees as a mission to uphold his father’s legacy.

“When my father passed, he didn’t have a record deal or any records in the stores. He didn’t care. I said, ‘Dad, you know you really should get your record in stores. A.) How are you going to make any money? And B.) People should hear your music. People want to hear your music. You shouldn’t just leave the world hanging with no record.’ He was like, ‘Well, I suppose so....’

“And so I’ve taken that on as my job, from when he passed away. OK, let’s get everything back on the shelves, in perfect order. Obsessive compulsive. In the same-sized boxes, with the lyrics and the photographs. Then maybe in 20 years time I can go on being me, and carry on with my life. But it’s gonna take me 20 years! We’ll do a 50th anniversary for The Concert for Bangladesh as well. We’re looking into that. Everything’s been put back two years because of the pandemic, but we’ll get it done.”

I wish my dad could hear this. He would have been so psyched

For now, the 50th Anniversary reissue of All Things Must Pass offers plenty to keep us occupied. Perhaps more than anything else, it offers a vital connection with a gifted artist and highly evolved human being whom many of us miss dearly – but few, if any, as much as his only child.

“I wish my dad could hear this,” Dhani says. “He would have been so psyched. It sounds timeless, but it also sounds like it could have been recorded yesterday.”

- All Things Must Pass is out now via Capitol.

In a career that spans five decades, Alan di Perna has written for pretty much every magazine in the world with the word “guitar” in its title, as well as other prestigious outlets such as Rolling Stone, Billboard, Creem, Player, Classic Rock, Musician, Future Music, Keyboard, grammy.com and reverb.com. He is author of Guitar Masters: Intimate Portraits, Green Day: The Ultimate Unauthorized History and co-author of Play It Loud: An Epic History of the Sound Style and Revolution of the Electric Guitar. The latter became the inspiration for the Metropolitan Museum of Art/Rock and Roll Hall of Fame exhibition “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll.” As a professional guitarist/keyboardist/multi-instrumentalist, Alan has worked with recording artists Brianna Lea Pruett, Fawn Wood, Brenda McMorrow, Sat Kartar and Shox Lumania.