Meshuggah’s Mårten Hagström: “Fredrik is the mad guitar genius. So for him to come back was natural and made me want to go on with it, too”

Hagström takes you inside the Swedish extreme metal masters’ punishing new album, Immutable, and the triumphant return of co-founding guitarist Fredrik Thordendal

When the coronavirus pandemic shut down the music industry in 2020, Swedish technical, experimental death metal band Meshuggah only had two tours left for their 2016 album The Violent Sleep of Reason.

They were pretty much already scheduled to return to writing mode for what would turn out to be Immutable. But there were other obstacles, aside from Covid, that left the future of the band in jeopardy.

The cracks in the Meshuggah fortress appeared gradually and were largely due to co-founding guitarist Fredrik Thordendal’s waning interest in the band. Back in 1996, he started working on the side project Fredrik Thordendal’s Special Defects, and a year later he released the album Sol Niger Within.

But he remained with Meshuggah the whole time and was back in full writing mode in time for 1998’s Chaosphere. For the next 15 years, he remained dedicated to his main band in the studio and on the road, but his desire to experiment more with shorter songs and psychedelic atmospheres nagged at his psyche.

In 2011, he started spending more time on the still-unreleased second Special Defects album. He wrote little for Meshuggah’s 2012 record Koloss and didn’t conjure a single riff for The Violent Sleep of Reason, though he tracked all his leads and agreed to tour. Eight months after the release of the record, however, he left the band right before a planned U.S. tour with Megadeth.

“I can’t say it completely took us by surprise,” shrugs guitarist and main songwriter Mårten Hagström from his home in picturesque Umeå, Sweden, about 400 miles from his bandmates in Stockholm. “He just stayed with us until one day he said, ‘I’m sorry. I need to step off to build a studio for this project. I can’t tour.’

"We weren’t excited about it, to say the least. But then again, we know Fredrik and we understand how he works. He’s like a stubborn dog. When he gets a bone in his mouth, he’s not letting go of it.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

With little time to prepare for the Megadeth tour, Meshuggah recruited Per Nilsson (Scar Symmetry, Nocturnal Rites) to fill in. He quickly learned Thordendal’s parts and, being with a new band member who was stoked to be on the road, everyone had a good time. To paraphrase Nilsson, he said his stint in the band was “the best time I’ve ever had at summer camp”.

But when camp was over, Meshuggah faced an existential crisis. They were right back in the position they were in when Thordendal bailed. The main problem was that his departure was open-ended. When he stepped away from Meshuggah, he told his bandmates to give him three and a half years to work on Special Defects, and then he’d decide whether or not he wanted to rejoin.

“I think he didn’t actually know he was going to come back,” Hagström says. “And we didn’t know if he was going to come back. And then I realized, ‘Fuck, man, we’ve been doing this for 30 years.’ That really messed with my head. I started questioning whether I wanted to continue or if I really wanted to quit doing the band.”

I started questioning whether I wanted to continue or if I really wanted to quit doing the band

Mårten Hagström

With the world on hold due to Covid, Hagström and his bandmates decided they had nothing better to do than start writing a new album as a four-piece before figuring out what the future held for them and Thordendal.

Ironically, the situation created the right amount of tension for Hagström and Meshuggah to write their most creative, eclectic and emotionally expressive release since 2005’s Catch Thirtythree.

“We actually wanted this to be kind of like a Catch Thirtythree for 2022 – a long ride that’s kind of like a soundtrack that has parts that are a little bit surprising, and every song moves you into the next part,” Hagström says. “And what’s kind of funny is that this album and Catch Thirtythree are the only two of our albums that basically wrote themselves. What I mean by that is not that it was an easy process or that we didn’t redo stuff.

“I think we worked maybe more than ever on arrangements, really not letting anything go. Never. ‘Is this good enough? Is it really good enough?’ We were asking that question constantly through this process. But at the same time, there wasn’t a point where we said, ‘What are we doing? Where are we going?’It was all about emotion.

“As we were doing it, we knew it was flowing the way we wanted it to and we knew the parts worked together and were still instantly recognizable as Meshuggah.”

From the staccato opening gut-punch of Broken Cog to the off-kilter chuggery and desperate single-note squalls of Ligature Marks, Immutable is unrelenting, undeniable and of the moment – a fragmented thunderstorm that rolls like an apocalyptic soundtrack, matching the images of war, contagion and treachery that splash across cable news 24/7.

Thordendal’s reeling, swerving leads spiral through The Faultless – disorienting and as digestible as broken glass. At the same time, the nine-and-a-half-minute-long instrumental They Move Below crosses dark, Tool-style atmospherics with crushing psychedelic hooks redolent of Neurosis. And the undistorted album closer Past Tense is a balmy wind across a barren wasteland inhabited only by David Gilmour; what it lacks in volume, it makes up for in intensity.

During a poignant, revealing conversation, Hagström explains how working in isolation during a quarantine was artistically invigorating, the few paths Meshuggah sought to follow for Immutable, his weakness for Simon & Garfunkel and the return of Thordendal.

You’ve never been the kind of band to decide in advance what kind of an album you wanted to make. Was that the case this time or did the conditions in which you worked guide your decision to create a bleak, cinematic journey?

“No. We didn’t have a mission statement or a planned direction. But we did say we do not want anything to be filtered out early. Sometimes we’ve done that. We’ve pitched ideas and someone says, ‘Oh, maybe this is not 100 percent where we want to go,’ so we throw it away. This time everything was on the table. Granted, some stuff got left out because it wasn’t suitable.

“But for the most part, we decided there would be no strict rules. We said, ‘Don’t think about whether something is too long or too short or doesn’t fit what we’re doing. Just think about every song as something that puts you in a different room, a different atmosphere.’ And we figured if we did that, it would make for an interesting journey.”

Immutable is an interesting journey, for sure, but it doesn’t pull punches for the sake of melody or cohesion. Even some of the soft stuff is brutal.

“We have always wanted to keep the music instantly recognizable as Meshuggah, but to do different things within that framework. When you finish the entire album you should know what band you’ve been listening to, but we always want every album to have a different flavor. And with this it felt like, ‘Okay, we’re not 22-year-old guys with mustard in our ass, just going rabid all the time. We are an older band now and we want to reflect that.’”

As a guitar player, what keeps you excited?

“The writing process is still the most exciting part for me. When we did Nothing [in 2002], we started using eight-string guitars, which was a real big deal. It’s those kinds of changes that inspire me. For this, I guess I was really interested in putting in a lot of melodic stuff from things I used to listen to back in the day. I brought a lot more of that in and opened myself up to deliver a wider variety of what I am as a writer.”

Can you be more specific?

“Broken Cog and Ligature Marks have some riffs in them that are not standard-type power chords or single tone playing. These have more of a palm mute and then you mute with both hands. It’s almost like playing the slap bass but on four strings on the guitar. And for the clean parts, I didn’t want to limit myself at all. I just went for stuff that comes naturally to me when I sit down and get the guitar and noodle. So it was very intuitive that way.”

I really enjoy Simon & Garfunkel for the guitar work, where there’s so much harmony in it, but it’s not overstated

Did you record the clean parts on a six-string or did you do everything on an eight-string?

“I played the acoustic parts on an eight-string because I’m so used to that, but it hasn’t got a lot of the bass tones. Most of it could be played on a six-string. But in Past Tense there’s a lot of eight-string all the way through, especially the beginning part.

“I write a lot of clean stuff and I have computers loaded with them. I’ve got at least one entire album’s worth of atmospheric stuff. And some of it felt right to use on this album. It’s a long album. You want places to breathe in order to create that dynamic you’re looking for.”

Were there certain points of reference for the clean parts?

“When I was growing up I played a lot of acoustic guitar. I really enjoy Simon & Garfunkel for the guitar work, where there’s so much harmony in it, but it’s not overstated. And there’s such a light touch to the tone but it carries so much weight in your stomach.

“We’ve done that kind of thing before, but mostly in the interludes. That’s where I tossed that in, but it’s always been like, 'Okay, here we have a pummeling album and then we toss this in at the end for two minutes or if we need a breather in the middle.' I wanted to expand that approach.”

Did you write your parts separately and then get together in the studio to work them out together or did you get together and collaborate?

“Fredrik was out of the picture for the writing of this one. He recorded leads on four tracks, but he didn’t hear those songs until he got them from the studio rough mix, just so he would be able to play on this album.

“So it was basically me on my own, and [drummer] Tomas Haake and [bassist] Dick Lövgren worked together in Stockholm. We sent demo files back and forth. And then we had meetings. I drove down to the studio in Stockholm to work with them. Because of Covid, I didn’t go by train.

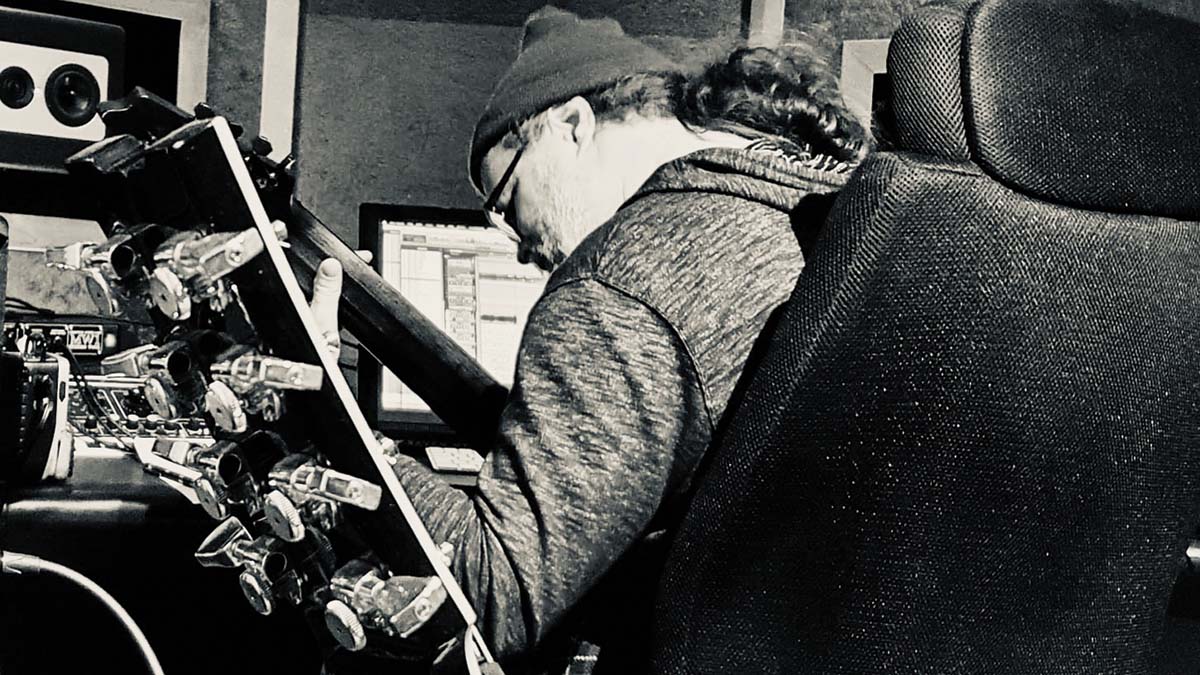

“I drove six hours away from other people. This pandemic catered to my working style, luckily enough. ’Cause going into a bubble and just being in a lockdown mode is when I write my best stuff. I have a little shed out in the yard where I have my home studio. So I go up in the morning, bring a pot of coffee out there and then I just start hammering away, dive deep into the rabbit hole and just get lost in my mind.”

What was the first song you wrote for Immutable?

“I originally wrote the intro riff for Broken Cog [in 2007] for Obzen. But I didn’t manage to pull it off. I thought, “This is not good enough. I don’t want to have it here.” I tried it again for Koloss, and it didn’t work.

“But this time around, I had an epiphany and I figured out what it needed. I was always intrigued by how it moved and how it sounded almost like a broken tank just rolling along awkwardly over the 4/4 beat. But I always tried to ratchet it up so that it would go from that riff into something more intense and pummeling.”

How did you make the song work?

“One night when I was actually not working on Broken Cog – I was messing around with some clean stuff for Light the Shortening Fuse – I went, ‘Wait a minute. Instead of using something heavier for Broken Cog, I’ll use this cool atmospheric verse.” It has the same 6/4 timing, and I went, ‘Yes! This is where it needs to go!’”

Did you collaborate less on this album since you were more isolated?

“Well, yes and no. We really tried to stay out of each other’s songs as much as possible. We normally do that to some extent, but this time the guy who wrote the song was really in charge.

“Suggestions were welcome, but the final say went to the main songwriter. And the reason for it was because we knew we would end up with a more dynamic album if less than four guys’ filters were applied to all this stuff. That’s why it’s an interesting journey from beginning to end.”

When did you all agree that Fredrik would tour with you again?

“Here’s how it went down. We decided to start making the album, and then three-and-a-half years point-blank from the day he said he wanted that much time off rolled around. So, we went over to his studio, had coffee, and played some pinball.

We’ve been together for so long. We’ve done so much shit together. We’ve been through so much

“We were just shooting the shit – no big deal. And he said, ‘How do you guys feel about me playing again in the band?’ And we said, ‘Well, how do you feel about it?’ And he said, ‘I’ve kind of been missing it. And this is my band and I feel I’m up for coming back. Is that okay?’”

How did you react?

“We were like, ‘Fuck, yeah! We’re family.’ We’ve been together for so long. We’ve done so much shit together. We’ve been through so much. And he’s such a big part of the lead guitar style of this band. He’s the mad guitar genius. So for him to come back was natural and made me want to go on with it, too.”

- Immutable is out now via Atomic Fire.

Jon is an author, journalist, and podcaster who recently wrote and hosted the first 12-episode season of the acclaimed Backstaged: The Devil in Metal, an exclusive from Diversion Podcasts/iHeart. He is also the primary author of the popular Louder Than Hell: The Definitive Oral History of Metal and the sole author of Raising Hell: Backstage Tales From the Lives of Metal Legends. In addition, he co-wrote I'm the Man: The Story of That Guy From Anthrax (with Scott Ian), Ministry: The Lost Gospels According to Al Jourgensen (with Al Jourgensen), and My Riot: Agnostic Front, Grit, Guts & Glory (with Roger Miret). Wiederhorn has worked on staff as an associate editor for Rolling Stone, Executive Editor of Guitar Magazine, and senior writer for MTV News. His work has also appeared in Spin, Entertainment Weekly, Yahoo.com, Revolver, Inked, Loudwire.com and other publications and websites.