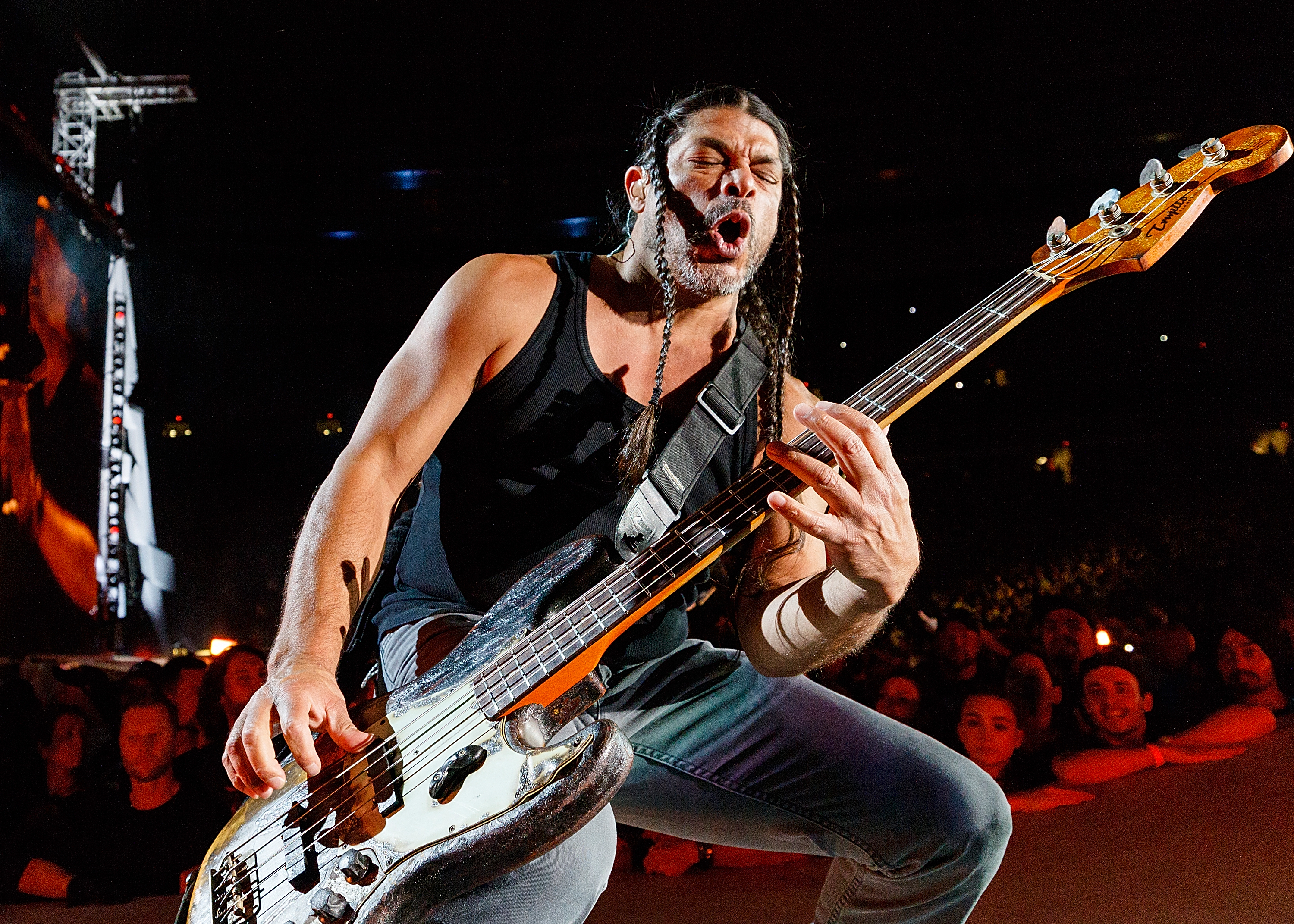

Metallica's Robert Trujillo on the art of simplicity

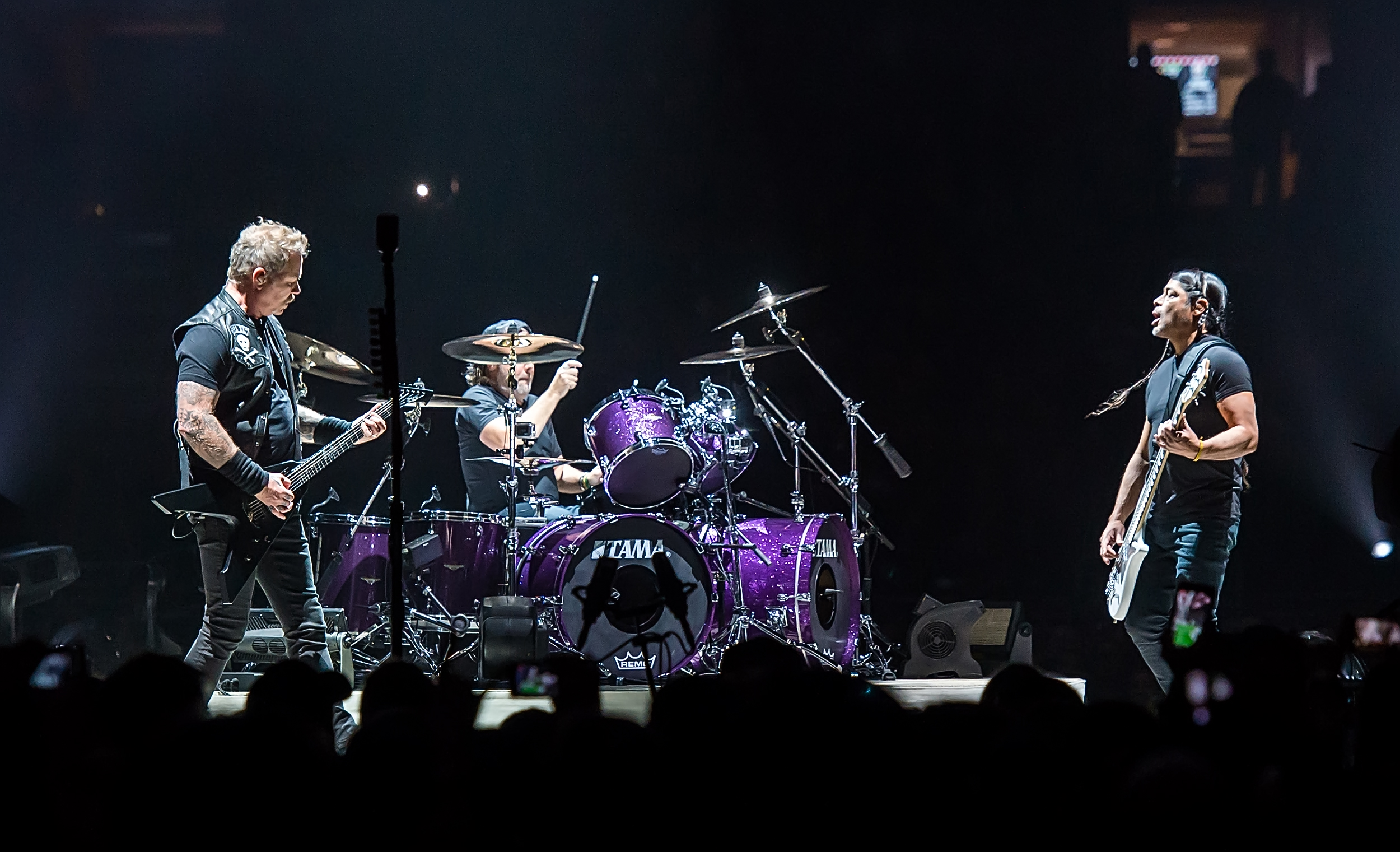

Robert Trujillo is calling from Guatemala City, Guatemala, the latest stop on Metallica’s current South American tour.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Robert Trujillo is calling from Guatemala City, Guatemala, the latest stop on Metallica’s current South American tour. Between gigs he’s doing press and answering questions about songs from Hardwired … to Self Destruct, the band’s latest CD. That isn’t so unusual—but this is Metallica, and Trujillo hasn’t even heard some of the final mixes yet. “I’m discovering the songs now,” he admits. “Some of the vocal stuff is different from when I last heard it. Right up until the last day of mixing, things are happening.” It may seem like a strange position to be in, but new material is a closely guarded secret for arguably the most successful heavy metal band of all time—even if you’ve been playing bass for them since 2003.

Metallica formed in 1981 and spearheaded the thrash-metal movement with classics Kill ’Em All [1983, Elektra] and Ride the Lightning [1984, Elektra]. The band’s third album, Master of Puppets [1986, Elektra], is one of the most successful and influential pure thrash-metal albums of all time. Unfortunately, original bassist Cliff Burton—famous for his bell-bottom jeans, fuzzed-out-wah-infused bass solos, and virtuosic technique—was killed in a bus accident while on tour in Sweden in 1986. That same year, he was replaced by Jason Newsted. Newsted’s style was more fundamental, but his root-note-heavy aesthetic is one of the ingredients that enabled Metallica to streamline its sound and achieve even greater commercial success. Metallica, often referred to as the “Black Album,” debuted at #1 on the Billboard 200 in 1991 and has since sold over 30 million copies worldwide. Songs like “Enter Sandman,” “The Unforgiven,” and “Nothing Else Matters” appealed to a wider audience, and Newsted’s chunky, Spector-driven tone is prevalent throughout. He left the band in 2001, citing private and personal reasons.

In 2003, after recording St. Anger [Warner Bros.] with producer Bob Rock on bass, Metallica enlisted Trujillo, who had initially carved out a niche for himself in the ’80s as part of the Los Angeles-based crossover thrash band Suicidal Tendencies. He then launched the funk-metal act Infectious Grooves in 1989, before moving on to Ozzy Osbourne’s band in the ’90s. Since replacing Newsted in 2003, Robert has also launched Mass Mental, his collaborative musical ensemble with Armand Sabal-Lecco. And, just last year he released Jaco, a documentary film he produced about the life of Jaco Pastorius, in association with Passion Pictures.

In terms of production, Hardwired is one of Metallica’s best-sounding records, but it might also be the most bass-centric. Burton may have had more freedom to express himself, as demonstrated on songs like “(Anesthesia)—Pulling Teeth” [Kill ’Em] and “Orion” [Master], but never has the bass been as present within Metallica songs as it is on Hardwired. After the much-maligned mastering job on Trujillo’s debut, 2008’s Death Magnetic, bass players worldwide will rejoice over just how listenable this record is. For examples, check out his muscular, rhythmic counterpoint to rhythm guitarist James Hetfield’s furious, militant riffage on “Hardwired,” or the gargantuan groove on “Dream No More,” or Robert’s restraint on “Halo on Fire.” His performances on “Moth Into Flame” and “Atlas, Rise!” are clear and audible, strengthening the grooves and supporting the riffs with aggression, grace, and simplicity. Heck, there’s even a full 34-second chordal bass intro to “ManUNkind” and a distorted bass solo on “Spit Out the Bone,” both of which harken back to Burton-era Metallica. It’s as if the rest of the band finally realized they have one of rock’s toughest bassists in the fold, and that it’s wise to incorporate his personality and give him some room in the mix.

“It’s taken eight years to do this,” says Trujillo. “It’s a journey we’re taking, and [for me] this is only the second step. There’s going to be another step, and I’m sure that next step is going to be even more involved in a collaborative sense.” Trujillo sounds genuinely ebullient about refining his approach into what he calls the “art of simplicity,” and he was extremely forthcoming about the triumphs, challenges, choices and techniques that inform his role in metal’s biggest band.

How would you describe your role in Metallica?

I always tell people that I’m like Joe Walsh in the Eagles. I’m here to support them. I’m here with my bass every day ready to jam.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

What were the most challenging aspects of working with them when you first joined?

One of the most intimidating things is showing James an idea that’s a bit challenging. I remember showing him the “Suicide & Redemption” riff (Death Magnetic), and it was a little tricky. If he doesn’t get it within the first few minutes, he gets a bit impatient. I find this with a lot of people that I work with, whether it’s Jerry Cantrell [Alice In Chains] or James. It’s intimidating because these guys are masters of their craft. It can be a scary thing.

How would you describe the writing process for an album like Hardwired?

Everything we do revolves around jamming; that’s where a lot of the ideas blossom. We have a jam room [backstage], and before we go on every night, we play. But a lot of the riffs come from James. He’s the type of guitar player where, if he’s adjusting the tone knob on the amp, he’s going to come up with a riff. So we always document everything that comes from that. And the jams that happen backstage are recorded as well.

You have a songwriting credit on Hardwired with “ManUNkind.” How involved are you in the process?

It’s a weird thing. On this album I had plenty of ideas prepared, but James already had so much stuff. On Death Magnetic I didn’t have so many ideas, but I had more writing credits. Hardwired was really centered on James’ riffs. Initially, “ManUNkind” was something that I had prepared and envisioned as an instrumental. Then James and I jammed together, and it became this beautiful piece of music. As far as arranging goes, a lot of that process comes from Lars [Ulrich, drums] and James. I’m there to support them.

You sound a little surprised that “ManUNkind” is on there.

I only found out about it last week; I didn’t know. That’s kind of exciting for me. It’s beautiful that Lars included [my intro] in the song.

It has a bit of a Jaco influence, like “Continuum” or “Blackbird.”

It’s classic Metallica, but there is that Jaco ingredient. Anything that I create, I’m always pulling from my influences. On a lot of the Suicidal Tendencies music I’m playing fretless bass, like the fretless intro to “You Can’t Bring Me Down” [Lights … Camera … Revolution!, 1990, Epic]. There’s a lot of that in my writing.

Is it a conscious decision to put those influences in there?

I’m always reaching and connecting with people like Anthony Jackson and Jaco. All of the music with Infectious Grooves was inspired by Jaco—hands down. Along with Larry Graham, he was my #1 influence with that band.

When you’re young, you’ve got lot of fire, and you try a lot of different things—there are no rules.

Yes, and whether it’s good or bad doesn’t really matter. It’s that punk attitude. I wasn’t trying to learn Jaco songs note-for-note; I think I do that more now. But it wasn’t about that when I was composing back in the days of Infectious or Suicidal. It was more about taking the attitude and the technique and applying it to original ideas.

How does that apply to a band like Metallica, which requires a bit more restraint in the bass parts?

I always try to cater to the balance of the song and being simple, but at the same time, some of the intros, and some of the stuff that pops out in the mix, is all influenced by my heroes. A song like “Suicide & Redemption” is influenced by Anthony Jackson. I go there. I’m playing the low B, I’m playing something repetitive, and I’m doing it really heavy. That comes from him.

Jackson, Jaco, and Graham seem like unconventional influences for a bass player in the world’s most popular metal band.

Well, Geezer Butler is another huge influence. He has this sense of melody within a line that just always fits well within the chord progression or riff, so I always try to pull from him, too. It’s great when you can find that ingredient that works for you and apply it.

Overall, your lines on Hardwired are fairly straightforward.

As a bass player on this stuff, what was really fun and interesting was the art of simplifying and finding ways to create a pulse within the song, whether it’s fast or in-your-face and aggressive. Finding a certain rhythmic pulse that complements James Hetfield’s guitars—and also the drums—was something that was different from anything I’ve ever done in the past. That was the great thing about Greg [Fidelman, producer]: He helped me find the rhythms that were going to work against the guitars, so I’m not playing exactly what the guitars are playing.

I was curious about that on the song “Hardwired.”

It’s an interesting balance. On songs like “Hardwired” that’s where we actually started checking that out—going for a slightly different rhythm. It’s very subtle, but it creates strength in the riff. Normally in the past I’d go for mimicking the riff, and of course, on some songs, you play the same thing. But overall, I thought it was really interesting to break it down and find a rhythmic pattern that supported the riff by playing less. There’s a certain impact and power to that.

Do you have an image in mind for what you want the bass to sound like within a song, or how you want it to react?

I always try to envision a heavy punching bag, and I really think, more than any other time, we achieved that on Hardwired. Whether it’s the tone or the power of the instrument, it’s all there on this album. It’s present. In years past, even back in the day with Cliff, his presence was there and it was enormous, but the bass was sometimes buried. On this album it’s not buried; it’s right there with the other guys. And that makes me feel good for the future.

What else did Greg Fidelman bring to the table as a producer?

That guy is amazing; he loves bass and drums, and he supports the rhythm section. This is the best-sounding Metallica album, I feel, from the rhythm-section standpoint. The tones are crushing. The fact that there’s love for the instrument is really a beautiful thing.

What basses did you use?

We did a listening test where we had six different basses, and we recorded the same part of a song, like a blindfold taste test. You play through it several times, and then you listen back and try to figure out which instrument stands out, not knowing which instrument you’re listening to. There’s a specific Warwick 5-string that just took control of this body of music and owned it. The Warwick crushed it. Traditionally I’ve used a lot of other basses; I love Nash P-basses, and I love some of my old Fernandez basses, which were built by the old Tobias luthiers. I used a lot of those on Death Magnetic. But my Warwick 5-string dominated this album. You can hear the subtleties of the low B.

Is there a particular quality or character you’re looking to hear from the instrument when you’re doing these tests?

At the end of the day, it’s what’s most important for the songs. I’ve done albums where I changed basses for almost every song. On the album I did with Jerry Cantrell, Degradation Trip [2002, Roadrunner], I was using everything from old Fender Precision Basses to Tobiases. I have a really amazing Tobias 5-string that I recorded a lot of the Infectious Grooves and Suicidal music with; it was my go-to bass. And that had a strong presence on Jerry’s music. But at the same time, I also used flatwound strings on a Danelectro. That music called for specific instruments.

So what made Hardwired a one-bass record?

Hardwired is much more in-your-face. I did also use an ESP bass for a few songs, because it had a certain “sub-grit” that was very present. But that’s the kind of quality that went into this record: taking the time to do these tests and figure out which bass was going to take command of the music.

Do you generally prefer active pickups?

It just depends on the song or the era. I have a really strong right-hand attack, and that plays into it. What happens sometimes with the P-Bass, with my attack, is the string will hit the pickup. If I hit too hard, I get this weird click or clank, and with the EMGs I don’t have that problem. Now, with the older, more vintage thrash songs, there are times when I prefer to play a passive P-Bass. If there’s more of a retro vibe, I’m going to pull out the P-Bass 4-string.

Do you use two or three right-hand fingers?

I do everything from one to four fingers. Sometimes, with faster double-picking, I rotate my index finger back and forth so it’s sort of like you’re attacking down on the pad of your finger and then you’re coming back immediately with the nail. It’s like a rotation that serves as a pick technique. And to conserve energy on the index finger, I’ll switch to the middle finger and do the same thing. Sometimes I even throw in the ring finger, too. But it’s all to conserve energy.

What made you develop that technique?

Back when I first joined the band, I found myself running out of gas and cramping up. So I developed this technique to conserve energy and stay in the pocket. A lot of that double-fingerpicking works for me.

Are you applying that technique to up-tempo galloping grooves?

Actually, I developed a three-finger technique to keep up with the pace on some of the songs. When we play live, things get faster; it’s a natural occurrence with Lars and the guys. No disrespect—it’s just something that happens with all the energy. So, sometimes I’ll play a three-finger gallop technique that starts off with my ring finger and rotates. That way I can stay right in the pocket with James and Lars. But I had to learn all this. It was like I was lost when I first joined the band.

As you’ve matured as a player, what do you find your greatest challenge has been?

I’m always learning. When I did that album with Jerry Cantrell, I learned about the art of simplicity. Jerry is very specific about what he wants. He writes most of the bass lines, and he gets very specific about the feel the instrument. The presence needs to be felt, and the choice of notes needs to cater to what the guitar progressions are. There’s an art of simplicity with regard to specific notes and how they work with the note on the guitar and the vocal melody.

Complementing the vocals seems like an important but sometimes overlooked aspect of rock bass playing.

There have been times when I’ve prepared a bass part and we’re playing, and James is like, “That note conflicts with a note in the vocal.” So he’s thinking beyond just the guitar riff. I love being creative with players who challenge me.

Any advice for our readers?

I’m blessed to have worked with Mike Muir [Suicidal Tendencies] and Jerry and Ozzy Osbourne. It’s important to play your instrument and be prepared, but there’s another side to all this. You have to get along with people and be able to balance personalities.

Gear

Basses Warwick Robert Trujillo Artist Series 4- and 5-strings, ESP Trujillo 5-string

Pickups EMG w/Bartolini preamps

Amps Ampeg SVT-CL, Ampeg SVTIIPRO, Ampeg SVT-810E

Strings Dunlop Trujillo Icon Series (.045–.130)

Q&A With Tye Trujillo

Robert’s son Tye is only 12 years old, but he’s already turning heads with his bass playing. He’s in a band called the Helmets, which Robert mentors. We chatted with Tye to find more about this young gun.

Who are some of your influences?

I like Armand Sabal-Lecco, Cliff Burton, Justin Chancellor from Tool, and Geezer Butler.

What is it you like about their playing?

I like how Armand can play almost every style. I like Justin’s pick technique. And I like how Cliff Burton used distortion; it’s like a guitar. And I like Geezer’s bass fills.

Do you play with your fingers or a pick?

I do both. It just depends on the song.

Your main bass is a Fender Precision. What do you like about it?

It has cool bass sounds, but you can change it up on different songs. It’s versatile.

Do the Helmets perform covers or originals?

We play cover songs, but we’re trying to write more originals.

What’s next for the Helmets?

We’re trying to get in to record. We have some gigs in March, but we’re taking a little break to write enough songs for an album.

If you had to name one thing that makes you proud to play bass, what would that be?

I like that you can change the mood of the song. If you play a different note against the guitar chord, you can change the mood and the feel.