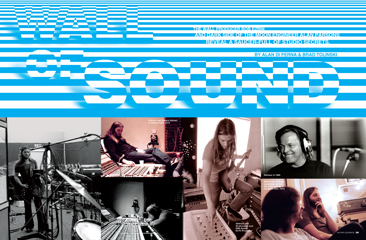

Pink Floyd: Wall of Sound

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Wall producer Bob Ezrin and Dark Side of the Moon engineer Alan Parsons reveal a saucer-full of studio secrets.

BOB EZRIN

How do you reason with two guys who once went to court over the artistic ownership of a big rubber pig? That was Bob Ezrin’s mission when, during sessions for The Wall in 1979, he agreed to co-produce the album with David Gilmour and Roger Waters. At the time, the legendary tensions between the two feuding Floyds had come to a head.

“My job was to be Henry Kissinger—to mediate between two dominant personalities,” recalls Ezrin from the safe perspective of 12 years. “Each one has a need to express himself in his own style. And sometimes those styles are very different.”

Seasoned by sessions with Lou Reed, Alice Cooper and Kiss, Ezrin was the ideal man to coproduce The Wall. He first discussed the project with Roger Waters “during the Animals tour, in the back of Waters’ limousine on the way to Hamilton, Ontario,” recalls Ezrin. “He told me that because he felt so alienated, he had this concept of building a wall between the band and the audience. We kicked the idea around in the car. Honestly, I never expected anything to come of it.”

But soon Ezrin found himself in the thick of Pink Floyd’s most ambitious recording up to that time. No mere referee, he had plenty of his own ideas for The Wall: “I fought for the introduction of the orchestra on that record—the expansion of the Floyd’s sound to something that was more orchestral, theatrical…‘filmic’ is the word. This became a big issue on ‘Comfortably Numb,’ which Dave saw as a more bare-bones track, with just bass, drums and guitar. Roger sided with me. So ‘Comfortably Numb’ is a true collaboration— it’s David’s music, Roger’s lyric and my orchestral chart.”

David Gilmour’s classic guitar solo on “Comfortably Numb,” says Ezrin, was cut using a combination of the guitarist’s Hiwatt amps and Yamaha rotating speaker cabinets. But with Gilmour, he adds, equipment is secondary to touch: “You can give him a ukulele and he’ll make it sound like a Stradivarius. He’s truly got the best set of hands with which I’ve ever worked. People always ask me, ‘How the hell did you get that astounding guitar sound at the end of “Another Brick in the Wall”?’ That’s just Dave direct, with a little compression. We used a form of double compression: first we put the guitar through a very aggressive limiting amplifier, compressed that output and overdrove it. The limiting amplifier makes it pop, and the compressor gives it a kind of density: the sound of being right in your face. But still, it’s nothing so involved that it would have made that part sound good if Dave’s playing hadn’t been so brilliant. That’s his first take, too!”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Ezrin was also called in to assist at the birth of the first (and, so far, the only) Pink Floyd studio album without Roger Waters: 1987’s A Momentary Lapse of Reason. Here a different kind of artistic debate arose. While Gilmour was keen to strike out in new musical directions, Ezrin felt a certain obligation to produce a record that wouldn’t disappoint the expectations of longtime Floyd fans.

“People are used to Pink Floyd delivering atmospheric, philosophical records, with lots of effects and ear candy,” says Ezrin. “I didn’t feel that a complete overhaul of the Pink Floyd sound or approach was called for at that time, particularly since Roger had left.”

Given the disparate set of songs that had been written for the album, Ezrin and Gilmour keenly felt the need to find a common thread to hold them together. They found that thread in a most unexpected place: right under their feet. Ezrin and Gilmour were recording on the guitarist’s studio boat, the Astoria, moored at the time on the River Thames. “Working on that boat was the most magical recording experience I’ve ever had,” says Ezrin. “Sitting every day and watching the geese fly, the school-kids rowing, and the little old English fishermen on the bank created a kind of river atmosphere that permeates the whole album.”

On a more practical level, the floating studio posed a few problems when it came to engineering guitar sounds. “It’s not a huge environment,” explains Ezrin. “So we couldn’t keep the amps in the same room with us, and we were forced to use slightly smaller ones. But after playing around with them in the demo stages of the project, we found that we really liked that sound. So a Fender Princeton and a little G&K amp became the backbone of Dave’s guitar sound for that record.”

When the song “A New Machine” created the need for something slightly larger, Ezrin and Gilmour responded on a grand scale. “We actually hired a 24-track truck and a huge P.A. system and brought them inside the L.A. Sports Arena,” the producer recalls. “We had the whole venue to ourselves, and we piped Dave’s guitar tracks out into the arena and re-recorded them in 3D. So the tracks that originally came from a teeny little Gallien-Krueger and a teeny little Fender, were piped through this enormous P.A. out into a sports arena, creating a sound like the Guitar from Hell.”

But what of the fabled big rubber pig? Well, Roger Waters claimed copyright ownership of the oversized prop, used at countless Pink Floyd live shows. But David Gilmour had a huge male appendage fashioned for the creature—thereby altering “its” artistic character enough to get around the copyright. Gilmour defiantly flaunted the porcine symbol during the Floyd’s Waters-less tour for A Momentary Lapse of Reason.

Aren’t you glad you never had to settle studio arguments between these two?

ALAN PARSONS

“Working with Pink Floyd is an engineer’s dream, so I tried to take advantage of the situation,” says studio wizard Alan Parsons with a touch of modesty. “Dark Side of the Moon came at a crucial stage in my career, so I was highly motivated. It was important to me, and I wanted to be sure that the job was done right.”

Parsons’ attention to detail obviously paid off: He won a Grammy Award for the best engineered album of 1973, and Dark Side of the Moon went on to ride the charts for a record-breaking 14 years. More than just an engineer, Parsons also functioned as Pink Floyd’s chief sonic architect. In addition to capturing the band’s inspired performances on tape and crafting Dark Side’s celebrated three-dimensional mix, Parsons was also responsible for creating the album’s twisted array of heartbeats, footsteps, clocks, airplanes and cash registers.

Understandably, Parsons asserts that it’s “difficult to remember all the details of something that happened 20 years ago.” Nonetheless, he gamely tried to field all questions related to one of rock’s great milestones.

GUITAR WORLD How did you become Pink Floyd’s engineer?

ALAN PARSONS It was simply through my staff position at Abbey Road Studios. I mixed Floyd’s Atom Heart Mother and they liked my work, so they recruited me to work on the sessions for Dark Side of the Moon.

GW Did Dark Side’s three-dimensional sound evolve over a period of time, or was it planned from the beginning of the project?

PARSONS Nothing specific was said, but Pink Floyd had a reputation for creating records that were in a class of their own. They obviously wanted something special.

GW Do you have any particularly vivid memories of those sessions?

PARSONS There are a couple. I have some fond memories of being left alone every once in a while to do rough mixes. Those were in the days when the comedy group Monty Python was popular, and the band would often leave the studio to watch them on television. I would stay behind and work, and it was during those times that I would get my best ideas. One of my contributions was to add the footsteps to the “On the Run” sequence. There were no band members present—it was just me with my assistant engineer, Peter James. Poor Peter had the job of running back and forth while I recorded him.

I remember instructing him to do things like “breathe harder.” [laughs] I was also responsible for the clocks in “Time,” which I’d originally recorded at an antiques store for a sound-effects record. Each clock was recorded separately, and we just blended them together.

GW Did the band compose much of the album’s material in the studio?

PARSONS Not really. They’d already performed a version of Dark Side in concert before they went into the studio. It was originally called “Eclipse.”

GW What about “On the Run”? I always assumed that it was created in the studio.

PARSONS You’re right. “On the Run” is an exception. That was pretty much Dave’s studio creation. He programmed a random sequence into an early VCS3 synthesizer and experimented until he found something he liked. All the basic sounds—including the bass and percussion sounds—came as a mono feed from that one synth. It’s funny, because most people assume that “On the Run” is composed of several overdubs. It’s actually a one-off performance.

GW Were there any specific technological factors that contributed to the album’s space-age sound?

PARSONSDark Side was recorded at a time when quadraphonic systems [systems using four channels to record and reproduce sound] appeared to be on the horizon. For example, a lot of the effects on the album were designed with quad reproduction in mind—most notably the introduction to “Money.” The idea was that each part of the cash register would emanate from a different speaker. As a result, lots of time was spent recording each segment of the sound effect on discrete channels. Obviously, no one knew that quad systems would eventually fizzle, but I would say that thinking in quadraphonic terms probably made us more careful about how we recorded the effects.

GW David Gilmour’s guitar sound on Dark Side is massive. Do you recall how it was recorded?

PARSONS David was very much in control of his sound system. We rarely added effects to his guitar in the control room. Generally speaking, the sound on the album is pretty much what came out of his amp. As I recall, he used a Hiwatt stack and a Binson Echorec for delays.

GW What kind of board did you use?

PARSONS A custom-built, lategeneration 16-track EMI board. It’s been reported that we used a 24-track board, but that’s not true. Believe it or not, almost all the tracks are second generation. We often ran out of tracks and had to bounce.

GW Do you think Dark Side could have been recorded using today’s colder-sounding digital equipment?

PARSONS I don’t see why not. The album is just the combination of four talented people with some good songs and good ideas. These days, the only difference is that it’s difficult to be original with sound. Those Japanese black boxes just make it too easy to dial up good sounds, but not necessarily original ones. Back then, we really had to work at it. It was literally a fight to reset the delay effect on “Us and Them.” We spent a tremendous amount of time hooking up Dolby units and realigning machines at the wrong tape speed to accomplish that effect. “Us and Them” was all done with tape delays because digital delays didn’t exist then. All these things took hours to set up.

GW I understand that you helped remaster the CD edition of Dark Side of the Moon for the Shine On Pink Floyd box set.

PARSONS That is correct. I received a call from James Guthrie, who became the band’s engineer after I left. He was supervising the remastering of the Pink Floyd box, and he needed some technical information regarding those sessions. I happened to be in the vicinity of the studio where he was remastering, so I went down. Basically, we discovered that the master tapes were in pretty good shape, and all we had to do was add a little brightness to the top end of the tracks. I felt very pleased with what we did, and feel that the version of DSOTM on Shine On is the definitive version.