Robbie Robertson: "The guitar is still a big point of discovery to me - it’s infinite"

The Band's iconic guitarist on scoring The Irishman with Martin Scorsese and his atmospheric new solo album, Sinematic

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Robbie Robertson, former backing guitarist for Bob Dylan and six-string mainspring for The Band, has a confession to make. He’s not really a rock musician.

“You know, sometimes I have felt over the years – and maybe now more than ever – that in the songs I write, it’s almost like I’m scoring the songs [as if for a movie] instead of following some kind of rock ’n’ roll tradition,” he says, explaining that his richly emotive playing is often inspired by imaginary film scenes played out in his imagination. “There’s a mood, there’s a sound, there’s a heartbeat. There’s a thing going on that takes me inside the story and takes me inside this little movie that I’m writing.

“It’s kind of a second nature for me,” he admits. “I don’t know if subconsciously I think I’m in a different line of work from other people in music [laughs]. I don’t know. I don’t know that I completely understand it either… and my feeling about that is it is quite instinctual. I really don’t know why I’m drawn in that direction, but it feels good, so I go with it.”

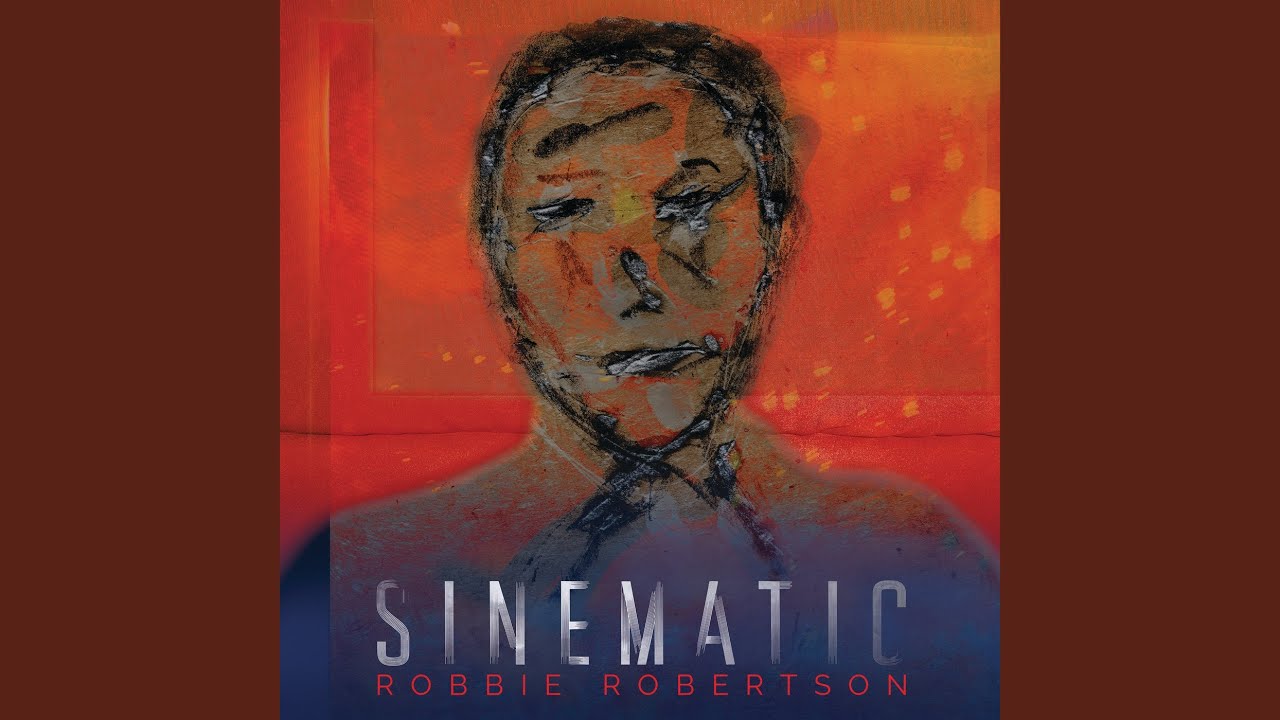

It’s not too surprising, then, that Robertson’s new solo album, Sinematic, consists of a series of emotive, richly textured songs that are like short films in themselves: dark-edged portraits of gangsters or yearning ballads that look back on the glory days of his time in The Band. When we caught up with him, he explained how to use guitar tone like a film director uses light – to evoke an atmosphere and tell a story through sound alone.

You’ve known and worked with Martin Scorsese a long time. Has that association with such a great film-maker taught you anything useful about storytelling that you’ve used in your music?

“I’m sure it has had a deep effect… but it’s subconscious to me. I can’t pinpoint what it has done. It’s like with this project, with Sinematic, I did a lot of art that goes with the album. And it’s stuff that I’ve done for a long time, but it was just personal to me. And I have no understanding of why or where it comes from, but it is just a natural flow that I do because I can’t help it.

"I make records, I write songs, not because I go out on tour and I kind of need something to tour with. Like I said, it’s like I’m in a different business. I’m not trying to figure out what’s trendy. I’m not trying to figure out if somebody will like what I’m doing – I’m just doing it because I can’t help but do it. And it makes me feel good. So that seems really important to me. But as far as all of the usual reasonings behind things or where stuff comes from goes… I like the mystery as much as I like the knowledge.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“The guitar itself, to me, is still a big point of discovery and it’s infinite, and that’s why I love it so much”

As in Scorsese’s movies, some quite nasty characters from the criminal underworld crop up on Sinematic. What’s the fascination with people who commit serious and morally troubling crimes, do you think?

“Well, sometimes this has to do with the background you grew up in – and Martin Scorsese grew up in Little Italy in New York City, living right next door to the Mob. And the neighbourhood is the Mob, so it’s kind of second nature. And where I grew up, in my family, some of the people… my relatives… were that. They were part of the Mob and part of the underworld and all of these things, the way they blend together… somehow they end up in your work because it’s who you are and it’s what you know.

“So the fact I’d been working so long with Martin Scorsese, who has been known for making movies about outrageous and a lot of times violent characters, because of his background… well, I had the same thing. And we’re both drawn to that because of that second nature. It’s not because I’m like, ‘Ooh, let me think of something dark and nasty to write about.’

"It’s just like this movie The Irishman [Scorsese’s New York crime drama for Netflix]. The main character is this guy where he found himself in that world and he’s just doing his job – he’s just waking up in the morning and going to work. And that’s the line of work that he’s in.

"So talking about these characters that are outrageous and that extreme fascinates us. But it all just somehow seeps back to your growing up and your background. Because of that, it’s like a magnet – and every time it’s around you get pulled in.”

Once Were Brothers from the new album is a very personal statement about The Band. What was special for you about that group?

“I have such a deep, deep place inside for my relationship with the brotherhood of The Band. A lot of groups think they had a strong bond and grew up together and that kind of stuff. In the documentary Once Were Brothers that’s just been finished… Eric Clapton comments on it and talks about it, Bruce Springsteen talks about it, and it’s a thing that in the case of the group The Band was unique – it was different.

"There are songs on the album like Dead End Kid, which is about when I was growing up. And people who come from our background… you’re lucky if you don’t end up in prison. But I’m like, ‘Wow, no, I hear something, I feel something and I’ve gotta chase this.’ And they’re like, ‘Yeah, that doesn’t happen for people like us.’ Hence the phrase ‘dead end kid’. Once Were Brothers was an expression like that, too.

“Now that three of the other guys in The Band have passed away, it’s only Garth [Hudson] and me left – and Garth doesn’t have the greatest health situation and it’s just heartbreaking to me. There’s such a deep warmth inside of me for that brotherhood and the relationship I had with these guys. I couldn’t help but embrace it.”

The guitar tones on Dead End Kid are lovely – the whole album sounds rich. How important is timbre and tone to you?

“A lot of it is a sound that I’m searching for. I’m always in search of a sound I’ve loved in records all my life – when I’d hear a record and it was not only an interesting piece of music, but there was a sound. I’m just drawn to that and it’s part of my cinematic philosophy as well. So I mess around until something helps me tell the story in the sound that I’m looking for, and I have different pedals and effects that I like to mess around with.

"But that’s my composition period and then I go in and record [what I’ve composed] with other musicians. Sometimes I find the exact sound I need when I’m writing it and sometimes I discover an effect later on that I think helps paint the atmosphere and tell the story.”

I don’t go into the studio saying, ‘Here’s what I need to do.’ I go in and I try to just allow myself to be open

What specific role does the guitar have in your songwriting these days?

“You know, it’s a tool and whether I write a song on the piano, the keyboard, on the guitar, whatever, it’s about going in with nothing in mind, no preconceived idea of whether you sit down with that instrument or another one. I don’t go into the studio saying, ‘Here’s what I need to do.’ I go in and I try to just allow myself to be open.

"I’m trying not to feel confined to any one idea in the beginning. It’s a total blank canvas; I’m just going to spray some paint on it and see where it goes. That is the organic beginning of composing – and the instruments are the tools. So I have different guitars that are different tools, if you like, and they make a certain noise that leads me in a certain direction. But just as much as I think I know what I’m doing, I’d rather not.”

What guitars are the most inspirational for you at the moment?

“I just got a guitar that I’m very excited about – it’s the exact guitar that Chuck Berry played in the beginning. It’s a Gibson ES-350T, plain maple colour, but it’s beautiful and Gibson just made me one. Because the sound of the guitar on those first Chuck Berry records is unbeatable. And also the sound that Scotty Moore played on some of those early records with Elvis, too, on those Gibson hollowbody guitars, was really beautiful.

"But my go-to main instrument is the Robbie special Strat they made [based on the metallic finish guitar Robbie used in Scorsese’s famous 1978 The Last Waltz documentary], where the pickups are moved and there’s certain electronics in them and a certain look to some of those guitars. There’s no pickup in the middle, because it gets in the way of my fingers, and the metal finish on it is brass. It’s such a beautiful-sounding and such a beautiful-looking guitar."

"So I love that and I also have some old Martins. I have a couple that are one-of-a-kind in the world that produce just amazing [tonal] textures, amazing sounds. So, yeah, I go for different instruments to try to catch myself off guard sometimes. Sometimes I’ll even start a song out on an old Fender six-string bass, just because it’ll take me somewhere where I don’t know where I’m going.

“On the last record I made, I did most of it with Eric Clapton and there was this beautiful musical relationship of guitars talking to one another, having a conversation back and forth. But on this record I had made a promise to myself that I wanted no ‘acrobatics’ whatsoever."

Sometimes I’ll even start a song out on an old Fender six-string bass, just because it’ll take me somewhere where I don’t know where I’m going

"Whether I was playing with Derek Trucks or whoever, we were all on the same page: make it haunting. Make it something that sizzles inside you. Go to that other place of emotion in the playing. I’ve heard all that other [showy] stuff. It all starts to sound the same to me. Let me hear you play one note – just like Miles Davis does – that lives inside you. That was much more interesting to me.

“For example, with another track on the album, Wandering Souls, I just want to hear the sound of my fingers. It’s all just fingers playing in different areas on the guitar – no picks, no nothing. Just the sound of skin on the strings. It reminded me a little bit of some things that I had experienced years ago, when I saw Curtis Mayfield playing and he played in a different tuning and did something that was so delicate and so touching. Because I went through this period where my guitar was on fire, you know [laughs]."

"I was young and I wanted the guitar to scream and I wanted it to be powerful and sing and do all of that stuff. I went through this whole period… and with Bob Dylan, he loved the excitement and the power of what I was doing with an electric guitar. And then when we got doing Music From Big Pink. By then there were a lot of people singing and screaming on guitar, but I had done it and been there – so I needed to go on a new place.

"So it was like, ‘How do I get texture? How do I get a feeling where the spaces are as strong as the notes?’ and just going in a different direction. Like we said, it was a search for a sound. And it’s not a sound that is all about an effect. I don’t know that there’s any effects on the guitar playing on Wandering Souls. The guitar itself, to me, is still a big point of discovery and it’s infinite, and that’s why I love it so much.”

- Robbie Robertson's Sinematic is out now on UMe. Order it here.

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.