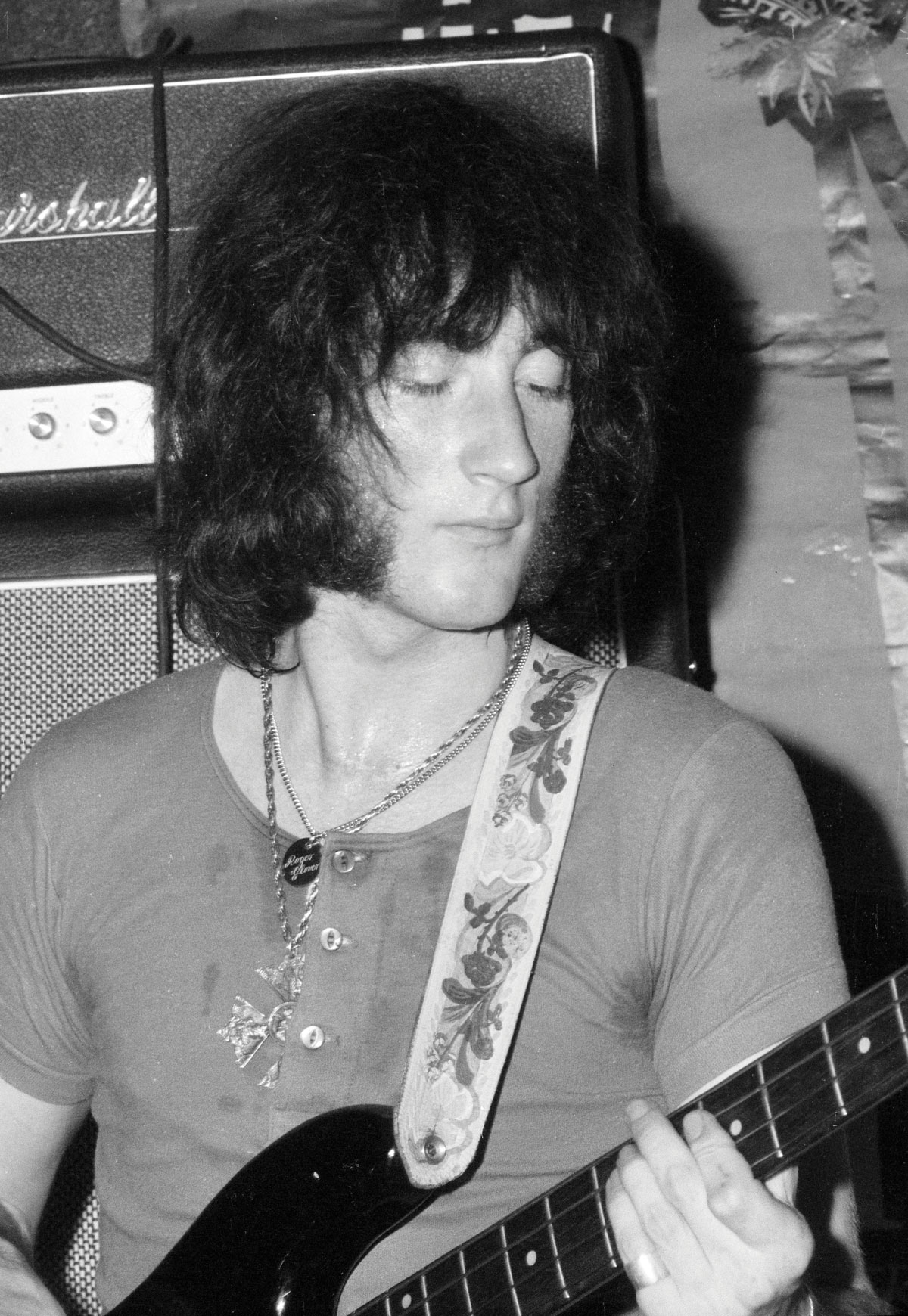

Roger Glover: "I'm a simple bassist. I’m not the virtuoso bass player that some people expect"

Deep Purple are the last hard rockers of their era still touring, and they’ve got some miles in 'em yet, says the man in charge of the band's low-end

Consider some numbers. It’s 52 years since Deep Purple formed, 51 since Roger Glover joined their so-called Mark II line-up, a cumulative 40 that he’s been in the band, 18 since the current lineup, Mark VIII, formed, and four years since they were inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame.

They’re about to release their 20th studio album – named Whoosh! for reasons which we’ll get into in a minute – and in doing so will add to the 100 million albums they’ve sold. Yes... 100 million.

Before the live concert industry was temporarily erased by coronovirus, Purple were planning to continue their Long Goodbye Tour, a jaunt which they’ve been on since 2017, more or less.

Added up, these are massive figures, culturally and numerically. There’s no wonder that Glover is on chirpy form when I call him at home in Switzerland about Purple’s new album. Is he all right, I ask?

“Apparently, yes I am! I’ve checked the whole body and everything’s working. Still kicking...” he replies. “I feel very lucky, I have to say. I live in the countryside, with lots of fresh air, but I really feel for people living in apartments and high-rises, with lots of kids in two rooms. I can’t imagine the tension. Fortunately, the rate of coronavirus infection is incredibly low throughout Switzerland.”

Have Deep Purple managed to escape the dreaded virus, then? “Yes. I’ve known a couple of people who’ve had it and recovered, but not in the band,” he says. “We’re all very careful, and isolating, but we’re out of work for a year, basically. More to the point, so is the crew, who we’re trying to help.

“It’s a problem for everyone, so we’re not alone. We’re better placed than some and not as well placed as others. That’s the way it is. You have to accept the cards you’ve been given.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Presumably there won’t be any Long Goodbye tour dates in 2020, then? “No, this year’s gone. All the touring we were going to do this summer is going to be shifted to the summer of 2021. I don’t know dates yet, but I don’t think there’s anything until then, unless we get together and have a bit of fun.”

Deep Purple – Glover plus singer Ian Gillan, guitarist Steve Morse, organist Don Airey, and drummer (and sole remaining Mark I member) Ian Paice – are a widely distributed band, making online sessions an obvious option in lockdown. However, an all-Purps Zoom jam isn’t on the cards, says Glover.

I remember in the old days the management or record company weren’t allowed in the studio when we were making music. There was a dividing line between business and music

“We’re five individuals stretched out around the world, and it’s difficult to coordinate,” he explains. “I wanted to do an online jam session, or something like that, but that was voted down because of latency or some other issue. Paicey’s [Ian Paice, drummer] doing a thing on YouTube called Drumtribe, though, which is interesting – it’s an insight into how we work.”

Have a look – it’s an insight into Purple at work in the studio, not a common sight by any means.

“I remember in the old days the management or record company weren’t allowed in the studio when we were making music,” says Glover. “There was a dividing line between business and music. We did the music, they did the business. That’s pretty much the way it’s been.

“We’re not secretive in the studio, exactly, but we don’t invite people in for a party, either. Paicey had cameras all over the place, for what reason we didn’t know at the time, so what you see of us in the recording, doing the actual takes, is new.”

Whoosh! is a great album, we tell him. “Well, thank you very much, thank you. One never knows, you know – there’s no round of applause at the end of an album,” he chuckles.

Informed that the music sounds both fresh and optimistic, he explains: “Yes it does, although there’s a hint of something. People have pointed out that there’s an atmosphere over the album that almost predicts this situation. Some of the songs are about mankind, and how time is passing; how we’re only on this earth, if we’re lucky, for 80 or 90 years, and then it’s gone. A lifetime is just a speck in time, in cosmic terms.

I suppose time became one of those themes, because this may be our last album

“I suppose time became one of those themes, because this may be our last album,” he ponders. “Every album we do could be our last album, at this stage, but there was a feeling about this one... Essentially what we do is we have a couple of songwriting sessions before we go into the studio.

“The first session is just jamming ideas, and we end up with 15 or 20 bits and pieces. We listen to them and take the ones that stand out, and hammer them into shape in the second session. Our producer Bob Ezrin helps there, and listens to what we’ve done.”

And does Ezrin always spot the potential hits? “Well, for one of the songs on the album, I have the note that he wrote, which says ‘I don’t know where this is going... Forget this one.' [laughs] But we wouldn’t forget it.

When Bob first came to see us in Toronto eight or nine years ago, what he liked about us was the musicianship and the spontaneity

“He said ‘Do you really think this works?’ and we said ‘Yes, it’s a great piece of keyboard riffing and we like it’, so we did it and it turned into one of my favorite tracks.“

How much of a ‘producer’ is Ezrin in the sense of demanding multiple takes from Glover? Does he need a few attempts to lay down the bass, or is it mostly nailed in a single take?

“Oh, I do it first time,” he nods. “When Bob first came to see us in Toronto eight or nine years ago, what he liked about us was the musicianship and the spontaneity. He said ‘When you play together, there’s a magic there that is vibrant and live and loose’ and he’s always tried to capture that in the studio.

“We’ll rehearse with him for a week before we actually go in the studio, so when we do start recording we don’t need more than one or two takes, playing live all together. If it doesn’t work after two takes, we won’t do it again.

“I might go in and repair a note here and there, but very rarely will I re-record a whole part, because it’s about the feel, not the precision.

Ian [Gillan] is there all the time, listening and making notes, and then he and I have a writing session all of our own

“At that point we’ve got a bunch of backing tracks with very few, or even no, ideas for vocals. Ian [Gillan] is there all the time, listening and making notes, and then he and I have a writing session all of our own.

“We went to an AirBnB place in Nashville and spent a week, hammering out ideas and looking for words and themes. That’s always been our modus operandi. Then we had a two-week recording session for the vocals in Toronto, and I’m there if I’m needed.”

Glover is a long-time user of Vigier basses, after spending his earlier career playing a variety of Fenders, Rickenbackers, Gibsons and even a Steinberger in and out of Purple and Rainbow.

The latter band was formed by ex-Purple guitarist Ritchie Blackmore, and Glover played with them from 1979 to 1984 while Purple were inactive. (We should also note that he’s a prolific producer, solo artist and guest musician, but if we go too deep into that we’ll take up the entire magazine.)

I’ve used Vigier basses for 27 years now, I think. They’re very reliable and easy to play

Asked about his basses of choice, he explains: “I’ve used Vigier basses for 27 years now, I think. They’re very reliable and easy to play, but when we did [Purple’s 2013 album] Now What?!, on the first day Bob suggested ‘The Vigier’s nice and all that, but you should try my bass’.

“He brought it out, opened the case and there’s this sort of battered old Fender Precision there. I picked it up and the strings were as dead as doornails. I said ‘I dunno... I like my Vigier, but yeah, I’ll give it a try. Let’s change the strings’.

“He said ‘No, no! Don’t change the strings, that’s a legendary bass, it’s been on albums by Pink Floyd and Peter Gabriel and Alice Cooper and everyone. Tony Levin’s played it, you know’.

“I’m a big fan of Tony Levin, so I thought ‘I’ll try it anyway’ and he was right, it records beautifully. It has a universal feel up and down the neck. It doesn’t disappear when you go high, or anything like that, it’s really a very nice guitar.

“In fact, I was so impressed with Bob’s that I went out and bought one in Nashville. I tried half a dozen vintage P-Basses, all of which were going for $6,000 or $7,000, and I wasn’t impressed.

“They were a bit floppy in the bottom end and I was about to give up, but then the guy said ‘Try this one’ and gave me another Precision. Bright pink, like a salmon, and I said ‘How much is that?’ It turned out to be a $300 Squier, and it is brilliant. I was knocked out, it’s so lovely. When I play a bass at home, that’s usually the one that I pick up.”

P-Basses are close to Glover’s heart, it emerges. You remember that bass you had as a kid that you later lost? [You’ll like this story.]

When I play a bass at home, the $300 Squier is usually the one that I pick up

“I started on a Precision, years and years ago, and unfortunately I sold it – I wish I’d kept it,” he says. “I was offered it back in the Rainbow days, after I mentioned in an article that I wished I’d kept my Precision. Some guy left a message when we were playing the Hammersmith Apollo in the UK, a little written message saying ‘I’ve got your guitar’ and a phone number.

“I went to see him the next morning, and at first I wasn’t sure it was actually mine, because it didn’t feel like mine; it felt very lightweight and it was covered in horrible purple paint – just painted on, not even sprayed.

“He pointed to a mod that I’d done to it – there was a hole from a screw that I’d put in – so it was definitely my bass, but he wanted too much money for it, so I let it go. It didn’t feel right in my hands, somehow.”

So does a P-Bass appear on the new album? “Yes, I played a Precision on most of the tracks. I only use the Vigier when I need to move higher, because it’s slightly easier to play, but I do love the Precision. For the stage, I’ll stick with my Vigier; a Precision sounds meatier in the studio, while the Vigier sounds more precise, with more of a modern bass sound.”

Glover is a four-string bassist to the core, he says. “I would never go to five. I once got up with a band for a jam session and the guy had a five-string. I said ‘I’ll give it a go’ but oh, I made a mess of it. I hit the B when I wanted to hit the E. I thought ‘Why bother to learn how to play this? I’m still learning to play a four-string’.”

I once got up with a band for a jam session and the guy had a five-string. I made a mess of it. I hit the B when I wanted to hit the E. I thought ‘Why bother to learn how to play this? I’m still learning to play a four-string’

Perhaps a five might be useful for any of Purple’s songs that have tuned lower over the years, we suggest.

“Some of the older songs that we play, the classics, they go down a tone,” he concedes, “because we were in our twenties when Ian started singing those songs, and at 75 it’s a little more difficult to do that.

“I’ve thought about getting a five-string for recording purposes, just to get a low D, instead of dropping the E string to a D, because that confuses me. I’m easily confused.”

Me too, I say. You forget that the string has gone down to D. “Especially when you’re on stage!” he laughs. “You don’t notice that you’re doing it, and you wonder why everyone’s looking at you, thinking ‘What are you doing?’”

Glover’s amps are TC Electronic, he explains. “I got turned on to them a few years ago. Their gear blew me away, it was so tight and round. If you can imagine a sound being a circle, it was that. It was perfect, and I use half the amount of speakers that I used to use, and it’s more powerful.

“We don’t use in-ears or monitors – we have side fills and that’s it. I tried in-ears for two weeks, but they frustrated me. Every time I wanted to hear something I had to rip them out, so it didn’t really work for me. I really want the feel of the power, and there’s only one way to get that, and that’s to go deaf, you know.”

How are the Glover ears holding up at the age of 74, we inquire? “Well, age plays as much of a part in loss of hearing as being in a rock band does. Probably more so, actually. My ears have been pretty good, although I haven’t measured them lately. There’s some damage, but they’re not bad.”

I really want the feel of the power, and there’s only one way to get that, and that’s to go deaf, you know

Presumably several decades of standing next to a world-famous power drummer doesn’t help? “You say Paicey’s a power drummer, but he’s not what you’d think a normal hard rock power drummer is. He doesn’t hit the things that hard, he hits them right, so they really resound.

"I’ve played with drummers who were much, much louder and raucous than him, and I don’t like that; there are no dynamics involved. His playing is much more nuanced, and you can’t be nuanced if you’re hitting them as hard as you can.”

How does it work with Vigier, we ask – do they send Glover a bass on request? “Yes, when I ask for one. If I say ‘Hey Patrice [Vigier, company owner], can you send me a fretless?’, he does. But I don’t bother him that much.”

He doesn't say, ‘I need 20 new basses, please?’ like the rest of us would?

“I would never do that. I’ve got enough basses as it is. I don’t know what to do with them. It’s not a bad problem to have, I know, and it’s not so much the guitars, it’s the cases. Where do you put the cases? They take up so much room.”

Does he still have the Rickenbackers from the old days? “I’ve got one Rickenbacker, the main Smoke On The Water one. I’ve given it to my daughter. I’ve still got the Fender Mustang that I used on Fireball [1971], the Gibson Thunderbird that I used with Rainbow...

“I’ve got quite a few. People have made me basses, with my initials in the paint, which is very nice of them, but I don’t really want to play a bass with my name on it. I don’t like wearing T-shirts with Deep Purple written on them either.

I don’t really want to play a bass with my name on it. I don’t like wearing T-shirts with Deep Purple written on them either

“The last time I did that was many years ago,” he says in amusement, “when I was living in Connecticut. I woke up one Sunday morning with no milk for tea, so I threw on jeans and a T-shirt and I went over to the local shop, still unshaven and half-asleep.

“I shuffled in the queue up to the cashier and the guy behind me said, ‘Hey! Deep Purple!’ I thought ‘Oh God, I’ve been recognized’ because I didn’t realize that my shirt said ‘Deep Purple’ on the back. Before I could turn around and say ‘Hi’ or shake his hand, he said, ‘Ah, they’re not as good as they used to be’.”

What’s the internal power structure in Deep Purple, we ask, perhaps a tad impertinently, now we come to think of it. Is there a band leader? “There’s no leader as such,” he says. “It’s very democratic, so we reach decisions just by talking to each other. I don’t think there ever was a leader, although some people may differ about that.”

In the early days, Ritchie Blackmore seemed to be a little more, shall we say, forceful than the rest of Purple.

“Well, it was a democracy, but Ritchie came out as the driving force of the direction of the band, not that he actually was the leader of the band. Since then we’ve always shied away from having a leader. Jon Lord was the acknowledged leader in the early days, because he could talk nice. He went to drama school and he had a good voice.”

We’re glad Glover has mentioned the fantastic Jon Lord – organist, raconteur, musical genius, Purple founder member – who died of cancer in 2012. I met him and liked him (buy me a drink sometime and I’ll tell you about it) and he occupies a special place in many people’s hearts, not least that of his friend Roger.

“He lives in me,” says Glover, sadly. “He was a wonderful man, and I miss him. Every time that I listen to something that he played on, I think how great it is. He taught me a lot.

“One of those things was ‘When I’m doing a solo, I’m not going to do multiple takes of it. If I don’t get it the first time, I might get it a second time, but after that, that’s it – I’m not going to fiddle with it.'

“He was purely spontaneous; he didn’t learn bits to put in. That wasn’t his style at all – he was a real jazz player in that respect. Some of the very recognizable solos he did – in Fireball, for instance – were off the cuff, not worked out. That was who he was.”

One last thing. Every time we meet Glover in this magazine, he tells us that he’s a simple bass player who likes playing simple bass parts. We always nod politely and then listen to the new Purple album, only to come across a bass part that is definitely complex. What gives?

“Well,” he considers, “I happen to be in a band that’s got something going on about it, and that has a drummer who is brilliant, one of a kind. Paicey said to me at our first or second rehearsal back in 1969, ‘By the way, I don’t follow, I lead’. And I thought ‘Okay. I know my place’.

“And actually that’s quite right – I couldn’t possibly influence Paicey. He’s a machine, all to himself, so I have to tuck in with him. I’m not the virtuoso bass player that some people expect. I’m a simple bass player, and sometimes I’m a little embarrassed about that, that people think I’m so great but I really don’t.”

There’s always something new when you’re a creative person

What’s the plan now, Roger? Back on the road when circumstances permit? “I want to resume as soon as possible. At our age, we don’t know how long we’re going to last anyway,” he says, semi-flippantly.

“One of the big secrets of life is that when you’re a child and a teenager, everything is new. Everything is an exciting experience. The first time you go to Paris; the first time you do this or that. Then you get to about 40, and you’ve done it all. There are very few surprises left, unless of course you try and surprise yourself.

“That’s what growing old is all about, and the great thing about musicians is that that doesn’t happen, because there’s always something new when you’re a creative person. You can’t stop writing and expressing what you think, or words or music or whatever it may be, it’s fresh again.”

There’s hope for us all, then. Is there anywhere that Glover hasn’t yet been? “The North Pole. No, I don’t really want to go there,” he chuckles. “We’ve been lucky enough to go around the world several times and go to all sorts of places. I find it hard to take in, sometimes: I think to myself, ‘How the hell did I get here?’”

Joel McIver was the Editor of Bass Player magazine from 2018 to 2022, having spent six years before that editing Bass Guitar magazine. A journalist with 25 years' experience in the music field, he's also the author of 35 books, a couple of bestsellers among them. He regularly appears on podcasts, radio and TV.