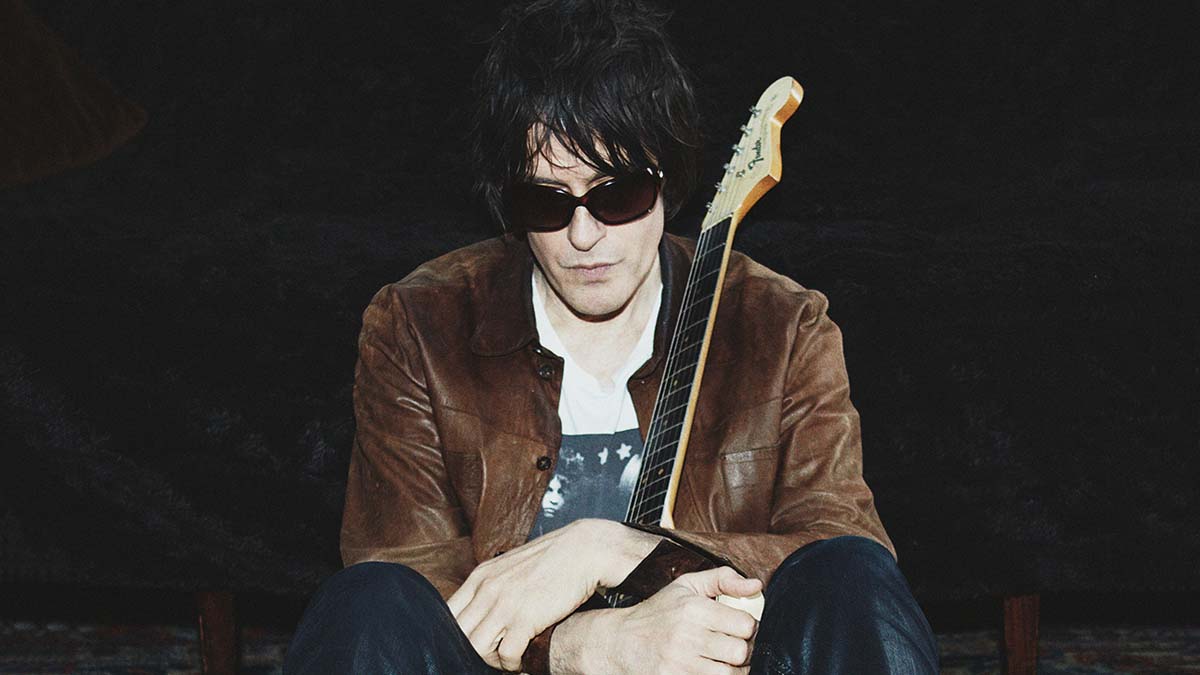

Spiritualized’s Jason Pierce: “I’m a big believer in pushing the simplest of ideas as far as they can go... you only need a chord to write a song”

The psychedelic space-rock guitar pioneer on why jamming doesn't work, the power of the simple idea, and smashing up your instrument

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Jason Pierce spent the 1980s co-fronting Spacemen 3 as J. Spaceman, with whom he developed a minimalist psychedelic sound inspired by Iggy Pop, The Velvet Underground and 1960s garage rock. The band split in the early 1990s and Pierce went on to form Spiritualized, under which name he still records and performs today.

The band’s second album, Pure Phase, broke sonic boundaries with its blend of space rock, guitar drones and shimmering effects. 1997’s Ladies and Gentlemen We Are Floating In Space gave the band its mainstream breakthrough and the NME awarded them album of the year (beating Radiohead’s OK Computer).

Since then, Pierce has worked with artists as diverse as Dr John, Yoko Ono, Ariel Pink and Black Rebel Motorcycle Club. He released a solo album, Guitar Loops, composed music for the 2007 film Mister Lonely and has had his songs featured in movies including V For Vendetta and Vanilla Sky.

April 22 sees the release of Spiritualized’s ninth album, Everything Was Beautiful. It’s a return to a more live sound, blending elements of blues, rock and roll, country, gospel and free jazz.

Still the scale is huge, with Pierce himself playing 16 different instruments and employing over 30 musicians, to create the expansive soundscapes the band are renowned for.

He has an experimental approach to guitar which, as he explains to TG, was forged at an early age…

Find your own path

“I got my first guitar when I was quite young, maybe seven years old. I vaguely remember a couple of lessons that didn’t make any sense. I learned like everybody learns, you just hit the thing, and after a few weeks you find you can do something else, and then it never stops. But if you like the sound of it, and you like what you’re doing, it’s endlessly fascinating.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“That’s the excitement and the thrill of electric guitar. Learning the rudiments, even learning the parts from other people’s records, never really interested me. It just felt like something that was too hard and too time consuming. That’s why I still can’t play anybody else’s songs.”

Ability isn’t everything

“Whatever it is about those doo-wop chords, 12-bar, the blues... there it all is. I’m not astounded by people’s abilities, or the way people play or the way they sing. It’s about passion, it’s about the soul, about the fever, the rush and the excitement of it, not about the ability.

“I still feel as inept as I did when I started. I still can’t recognise the key people are playing in. I will hit every single note on every single fret on the guitar until I find the one that matches.”

There’s a limited vocabulary for rock and roll

“I don’t think it’s important to look for originality. There is no originality in music, it’s all based on the same musical knowledge. I think you choose things on how close it is to the musical world you inhabit, or you love, not on some arbitrary fashion, or how original it is.

“And I guess when it comes too close, you say, ‘Okay, we can’t do that, that’s too close, or that’s not dissimilar enough.’ Often it’s hammering at it until something amazing comes. And not letting go. I edit up when making records. Most people edit twenty songs down to eleven. I edit four up to seven. If anything we’re doing is worth pursuing, then it’s worth trying to find the song in it.”

Jamming isn’t for everyone

“All bands form by osmosis. You spend time together and you get more and more into the same kinds of music on the road. That’s when we started to play some of the more free-form passages like The Stooges, The Velvet Underground, Sun Ra and Albert Ayler. But not showing your weird tricks, because that just sounds like five people in a room sharing what they can do.

“It only works when it serves the song. It’s not about playing - it’s about listening. That’s the problem with jamming: it seems to be a vehicle for one or two people to solo over. We never jam as a band. Even the word sounds like some kind of folly, like, why would you want to do that? The thing with improvised music is you can’t rehearse it, because then it completely ceases to be improvised.”

You only need a chord to write a song

“I’m a big believer in pushing the simplest of ideas as far as they can go. When most people get tired and think ‘I should go somewhere else with this’, I’m still thinking, ‘No this is amazing, what an amazing thing to be able to do’. I tend to hit the same things all the time on the guitar, but you only need a chord to write a song.

“Often I start by singing the lines. On the guitar I have to work things out, work out the structure, but if you sing the tune, you can go anywhere, you’re not held back by your ability to play. Most of it’s written like that.”

Songs find their own place

“With the song Crazy, I wanted a string quartet on it, but I couldn’t afford it. So we used the Mellotron and then suddenly we’ve got this country song that doesn’t feel like it should fit. It was always going to go towards a Patsy Cline, small-band kind of thing, and that’s where it felt comfortable.

“Songs find their own place to be. You push them around and you go with what works and then they find this place, whatever the intentions you had when you start.”

Brighter isn’t better

“I remember years ago working with Bob Ludwig in America. At the time he was mastering The Rolling Stones’ records and the record company constantly kept saying ‘Brighter, brighter’, like it was a competition.

“And he made them go out and buy the 1970s vinyl and listen to what was on the record, and they’re actually quite dark-sounding. Spotify and most of the streaming services have done that as well: the sound gets brighter and it’s coming out of smaller speakers. But making it brighter and louder doesn’t make it better.”

Find the parts that make sense

“A lot of this record was put down during lockdowns. We used the studio for stuff I couldn’t do anywhere else: small choirs, drum kits and percussion instruments. The guitars were done individually, so it wasn’t really about making arrangements.

“Each of the guitars is a different instrument. The [Fender] Jazzmaster sounds quite different from a [Fender] Thinline. So quite often playing live, it’s as simple as having three different sounding guitars that make the space for themselves.

“There are 200 individual tracks of music on some of these songs. When we play live we’re essentially a six-piece, so you have to find the parts that make sense and the parts that you need to cover, but not in a way that takes all the enjoyment out of playing it.”

Push things to their limits

“I spent a whole American tour smashing my guitars. I remember being on tour with the Dirtbombs, and Mick [Collins of the Dirtbombs] saying, ‘Please tell me those aren’t ’60s and ’70s guitars.’ And they were, they were getting destroyed, but it felt like that’s the tail end of trying to go as far as you can, when you’ve got nowhere else to go.

“And after a while my guitar tech said, ‘If you’re gonna do that, let’s give you a fake guitar so I’m not gluing your guitars together every night.’ And as soon as it became fake I didn’t do it. Because it wasn’t a show business thing, it was, ‘Let’s push this as far as it can go.’”

Keep an open mind

“It would be better if we took the songs out and played them live before recording them. It’s always been hard to do that, because then people have copies of the song ahead of the release. There’s something about the initial moment of contact with a song which is really important. Within a year of playing live, though, they’re almost a different thing.”

Record everything...

“The Beatles’ Get Back documentary was beautiful. Their process is exactly the same as anybody else in the studio. It’s what you do as an artist, you go through the moves. Obviously it’s been edited so you’re not seeing the kind of errors and mistakes and whatever, but John Lennon’s solos are the same every time he plays Get Back.

“It’s been worked out with the same process that everybody goes through to arrive at a song. And then little bits change as they perform. When we record, it’s interesting how fast people forget what they’re doing, and the good bits kind of go, they disappear for no reason. When you’re able to record everything, they don’t go, because you can always reference back.”

Jason Pierce’s guitar wisdom

Jason has an understated guitar style. “I’m not very big on my guitar playing,” he says. "I just put a guitar on my shoulder and hit a chord. And that’s the thrill. It's usually an open chord, an E or an A, something you can play with one finger!”

Jason varies the textures of his chord playing by changing the attack, sometimes using all downstrokes, in the style of The Velvet Underground, at other times picking the notes of the chord individually, as arpeggios. He’ll also vary the open chord voicings occasionally to change the sound.

For example, in the acoustic version of Lord, Let It Rain On Me from the Amazing Grace album, the chords are standard open D to G chords, but he shifts between a straight open D chord to an alternate D7 voicing to change the sound.

Jason Pierce on his gear

“I’ve got three Fender Thinlines, and there’s one of them, the pink one, that just feels like my guitar,” Jason says. “It chimes like a piano. I don’t even know what the pickups are, but they don’t sound like a regular Telecaster. That’s the one I just reach for. I like the [Fender] Jaguar ’cos it’s got these switches.

“You can just start messing with the switches and that gives you a whole new place to go. And with the [Fender] Jazzmaster you get another set of strings on the other side of the bridge, and you get a whammy bar; that’s going to take you somewhere else. But saying that, we’ve been rehearsing this week and I still feel like I can do better with the limited range of the Thinline.

“As soon as I use the switches and the sympathetic strings and all of that, there's more room to fuck up. With the Gibson L00 acoustic, it really did feel like it had these songs already in the body of it when I bought it. I’ve never really written on acoustic guitar before, so maybe that's part of it as well. It’s easier to play open C, F and G on an acoustic than it is on the electric. It’s a beautiful guitar; it’s from the 1920s.”

“Not a lot has changed in my guitar sound over the years,” he says. “I’ve got two distortions, one’s a tube. I’ve got the Coloursound Wah. I’ve got a Vox Invader that’s got all the trems, distortions and tone bender built into it, so if I want something a little bit more extreme I’ve got that to hand.

I experiment with new sounds a bit in the studio, but it's like sitting with synths and going through every single tonal possibility – 99 percent of it just doesn't interest me. And then as soon as I hear a Farfisa, or a Vox, or a Fender Rhodes, I'm like, ‘There it is.’ Because they’re instruments. I'm kind of fascinated with the fact that they're just instruments that make that noise.”

- Everything Was Beautiful is out now on Fat Possum.