“I had to stop buying records. I stopped being a fan of music – I felt that was affecting my individuality and my style”: SSD were hardcore legends, then Al Barile sold his guitar gear to buy a jet ski. Here’s how he found his way back to his Gibson SG

He may have been schooled on AC/DC, Van Halen and classical guitar, but Al Barile attacked his instrument with a vicious physicality inspired by his love of hockey. He looks back on his love-hate relationship with music – and the ‘80s SG he snapped after performing a jump-kick at CBGB’s

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

You’d hardly guess it from the bruising, brutalist fury of SSD’s 1982 landmark debut The Kids Will Have Their Say, but guitarist Al Barile took a lot of inspiration out of the gleeful, flipped hat power-pop riffage of Cheap Trick’s Rick Nielsen.

Before forming his cult hardcore crew – whose first release was just made available officially for the first time in 40 years via Trust Records – Barile grew up as a hard rock fan Lynn, Massachusetts, near Boston. He gravitated towards the straight-ahead crunch of AC/DC. He was also a card-carrying member of the Van Halen fan club, but didn’t quite see himself diving into the world of two-handed tapping.

Barile admits that Nielsen’s lead finesse was likewise slightly out of reach, but something about the way the Cheap Trick six-stringer comported himself onstage resonated with the fledgling player.

Initially, the teenage Barile wanted to emulate his hero – he brought homemade gifts to Nielsen at a local radio station, and angled for a Hamer Explorer as a starter guitar, before settling on a short-scale Fender Musicmaster. He quickly realized, though, that he needed to forge his own, ultimately violent path.

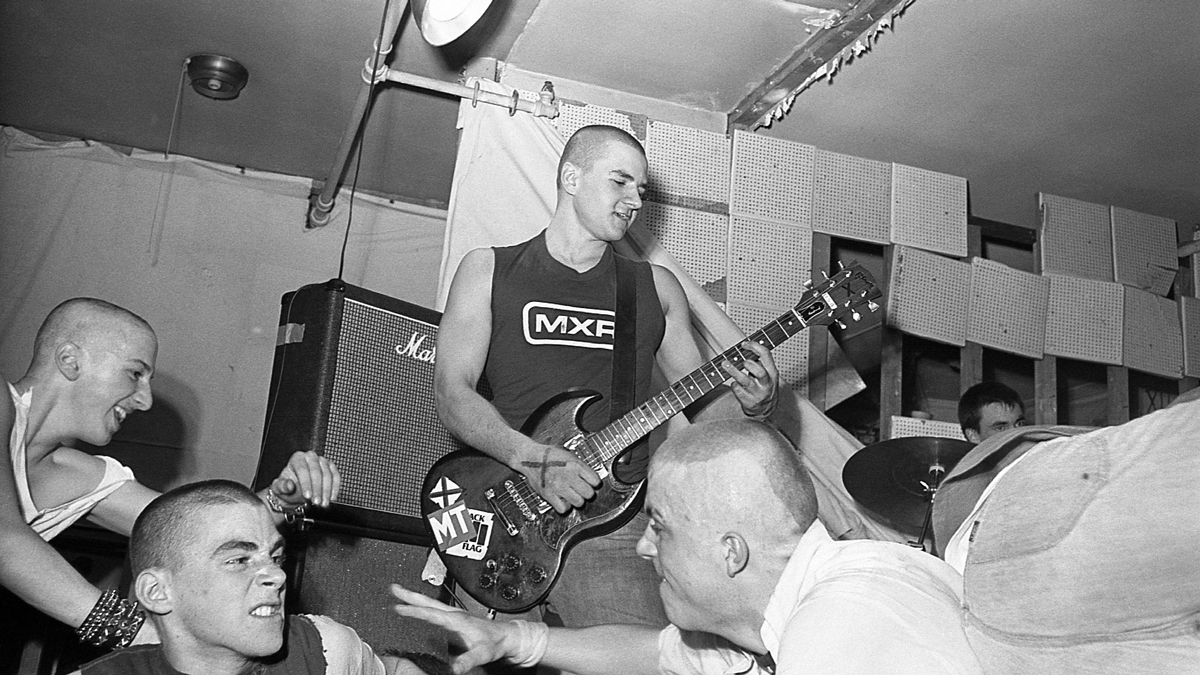

“What can I bring to the sport that other people don’t necessarily have?’” Barile recalls of his lightning-strike moment. “Sport” is a curious word here, but it’s integral to understanding the sonic intent of SSD. Before he ever picked up an instrument, Barile was a hockey player, and he wanted to bring that same imposing physicality to his guitar playing.

After discovering hardcore through the earliest Black Flag and Dead Kennedys records, he established a way to achieve the aural equivalence of his on-ice menace. By the time SSD came together in the early ‘80s (originally going by the name Society System Decontrol) Barile upgraded from his Musicmaster to a beefier, double-humbucker SG. He briefly studied classical guitar at college – you don’t get that on The Kids Will Have Their Say.

The record is straightforward but savage, mainly driven by his unrelenting, 16th-pattern power chord trills, underscored by the high B.P.M. blitzing of drummer Chris Foley, the rhythmic rawness of bassist Jamie Sciarappa, and the barbed-wire screams of vocalist David ‘Springa’ Spring. Fittingly, bandleader Barile’s riffs come at you like an illegal crosscheck determined to smash you through the boards and up into the nosebleeds.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

While distilling the essence of uglified ‘80s hardcore, the 20-track album is also marked with a few leftfield songwriting choices. Its most enduring number may be the sludging noise of its two-chord How Much Art Can You Take? An extended dread pervades Boiling Point, contrasting six vicious verse measures with a quick, two-measure chorus resolve. Headed Straight goes with a gruff and unsettling seven-measure framework in its intro.

Barile admits a lot of it baffled drummer Foley. “I used to present arrangements to him like Headed Straight, and he’d be like, ‘Yeah…that doesn’t make any sense,’” Barile says with a laugh. The guitarist clarifies: “I’m not saying I was doing Tool polyrhythms, but that conversation happened all the time.”

As formative figures in the scene, SSD shared stages around Boston and the Eastern Seaboard with first wave icons like Bad Brains, Minor Threat, Void and Dead Kennedys. While friendly with some of those acts, Barile made a point of not getting too chummy with their songbooks, for fear of tainting his own riffs.

“I’d be like, ‘Fuck, I think I’m playing Black Flag,’” he alludes of some early, accidental crossover. “I had to stop buying records. I stopped being a fan of music, because I felt like that was affecting my individuality and my style.”

Blotting out his contemporaries was arguably as hardline as the anti-drug Straight Edge ethos baked into SSD classics like Headed Straight and Forced Down Your Throat. Even back then, Barile knew he was taking an extreme position, at least when it came to his listening habits. “Looking back on my life, that’s the sacrifice I made. People laugh at it…but it was to maintain some kind of purity.”

Something he did learn from his peers in the Boston punk scene, however, was that SSD lacked the precision needed to go full-speed, full-time. “I remember seeing bands at [local venue] Media Workshop – like Gang Green and Jerry’s Kids – and watching them fly through a set. I’d be like, ‘They do it so much better than we do it.’ When I heard us playing that fast, I heard things that are out of phase. Not together. When I heard them playing, I heard tightness.”

I remember seeing bands and watching them fly through a set. When I heard us playing that fast, I heard things that are out of phase. Not together. When I heard them playing, I heard tightness

But the manic spirit of The Kids Will Have Their Say is a major part of its appeal, and part of the reason why original pressings often command four-figure prices. Barile originally pressed a small batch on his own Xclaim imprint, but those sold out by 1983. He never repressed because he was always focused on SSD’s future.

The guitarist calls their next step, 1983’s Get It Away EP, “the peak of what we were doing, because there was a certain organic chaos to it.”

Notably, that’s the record that introduces new lead guitarist Francois Levesque, who leveled up the intensity of street-tough stomps like Glue with a series of uncaged bends and gut-channeling phrases. “I didn’t really give him any guidance; I just said, ‘Do whatever you want,’” Barile confirms. “There’s an innocence to it. I didn’t overanalyze his playing, or overthink it.”

Though Get It Away accentuated the unfiltered aggression of SSD’s debut release, they were more hard rock than hardcore by the time they started plotting 1984’s How We Rock. The tempos started gearing down significantly and Barile’s picking became less like an overdriven cement mixer, instead favoring a more-controlled, mid-tempo chunkiness.

While his early, gain-surged sound drove a no-fuss JCM800 through a custom ElectroVoice cabinet, How We Rock added rack effects like an Ibanez harmonizer. That pervasive, watery tone, Barile argues, plunged the enduring appeal of that release. “Ruined the album for me, man,” he says. “I lost the power.”

1985’s Break It Up is even more divisive. Barile’s riffs on a newly acquired custom B.C. Rich Warlock are more melodic than mean-spirited, arguably hedging towards a mix of Flip the Switch-era AC/DC and the neon veneer of Sunset Strip metal. Levesque’s soloing moves from unstructured surrealism towards more traditionally bluesy territory.

Early on, Barile wrote lyrics for Springa that screamed for socio-political change; Break It Up starts off with the vocalist chewing the scenery with lines about ‘twiddlin’ your thumbs like Little Jack Horner.’ While oddly charming, it’s a world of difference. Though Break It Up seems in-line with Barile’s hard rock roots, the album name became a harbinger of sorts. Simply put, punk crowds hated it.

“They didn’t take to it well at all, and we started getting spit at. We played a big show in California – I think it ended up being with Social Distortion, and the audience did not like it,” Barile recalls. “I don’t think we got booed off, but they weren’t enjoying it. We could feel that in other cities too.

“So when the discussion came to literally break it up, it kind of made it easy. We weren’t high on the likability charts at that point… the sad thing is that we were happy with what we were doing. We thought we were hitting on all points.”

Barile broke up the band in the mid-’80s. In another extreme pivot, he marked the occasion by selling off most of his gear to buy a Kawasaki jet ski. “I felt that the purge was important. I was spending a lot of time in dark, dingy clubs,” he explains.

“After that many years of being involved in the music business, I wanted to breathe fresh air. When I got that jet ski, it was so I could be be touching the water and laying out in the sun. It was needed. But I used to feel guilt, thinking that I should be working.”

Funnily enough, he sold the ski in the early ‘90s so he could build a home studio and write music again, this time with the more alt-rock-leaning Gage, who issued a trio of LPs later that decade.

I got that jet ski so I could be be touching the water and laying out in the sun. But I used to feel guilt, thinking I should be working

While SSD’s music has pretty much been out of print since the ‘80s, it’s safe to say it has inspired generations of D.I.Y. musicians. Early on, they established the straight-ahead ferocity sound of the ‘Boston Crew,’ alongside fellow locals Negative FX and D.Y.S. Out of state they made fans of soon-to-be-famous folks like Soundgarden and Nirvana (the latter’s Krist Novoselic famously wore an SSD shirt through their Live and Loud concert for MTV).

Get It Away standout Glue has since become a beloved hardcore standard, recorded by Civ, Superchunk, Gel and others. The reissue of Kids leads a full-blown renrenaissance period for SSD, along with the How Much Art Can You Take? coffee table book Barile recently assembled with his wife and author Nancy and photographer Philin Philash.

Just before the pandemic, Barile even began entertaining the idea of a reunion, something unthinkable even a few years earlier. In 2006’s American Hardcore documentary, for instance, a scene of Barile and Springa hanging out together for the first time since their breakup is legendarily and comically icy. But time heals wounds.

Barile began reaching out to his old friends about staging a practice, and even managed to track down the early ‘80s SG he snapped after performing a jump-kick at CBGB’s back in the day – it’s since been tweaked into playable condition.

While SSD were gearing up to perform at a The Kids Will Have Their Say release event in Boston last month, those plans are sadly on hold. Last year, Barile was diagnosed with colorectal cancer. He continued relearning the band’s songs while undergoing chemotherapy and radiation treatment, but a recent bout with neuropathy has affected the musician profoundly.

“About two weeks after I finished the chemo, it started hitting my feet. It was in my hands, and I was playing through it – and it was not enjoyable at all – but when it hit my feet it was a whole new reality. I mean, I couldn’t stand up, really. I was getting dizzy. My balance was off.”

More recently, he learned his cancer is no longer in remission, and he’s readying himself for surgery. He concedes: “It’s not that important to play if I’m in pure misery. That’s when I pulled the plug.” Despite this, that hardcore fans can soon hold onto one of the genre’s holiest of grails is a feat unto itself. For Barile, the reissue is a testament to the lasting impact of the still blessedly oppressive SSD.

“It was just a great period of discovery, really,” he says. “Learning about so many things, and just making mistakes along the way. The creative process of writing all these songs… that feeling alone is what you woke up for every day for. I don’t regret one second of it.”

- For details on the reissue of SSD's The Kids Will Have Their Say, visit Trust Records.

Gregory Adams is a Vancouver-based arts reporter. From metal legends to emerging pop icons to the best of the basement circuit, he’s interviewed musicians across countless genres for nearly two decades, most recently with Guitar World, Bass Player, Revolver, and more – as well as through his independent newsletter, Gut Feeling. This all still blows his mind. He’s a guitar player, generally bouncing hardcore riffs off his ’52 Tele reissue and a dinged-up SG.

![SSD - BOILING POINT [OFFICIAL LYRIC VIDEO] - YouTube](https://img.youtube.com/vi/45ftxwy0a2Y/maxresdefault.jpg)