Steve Vai: Flex Appeal

Originally published in Guitar World, May 2009

With $5000 and a homebuilt studio, Steve Vai recorded an album that

made him a star and changed guitar music forever. On the 25th

anniversary of Flex-Able, Vai delivers the most in-depth look ever into the making of his shred-tastic debut and his plans to remake it.

“I was completely scared to death of being famous,” Steve Vai confides. “And I just thought, There’s no way I could sell this music I’ve made. I don’t even want to try to sell it! It’s too personal.”

The music that Vai is discussing is Flex-Able, his first solo album. Released in 1984, a quarter of a century ago this year, it has become a classic among fans of virtuoso rock guitar and a landmark of the Eighties shred phenomenon that forever raised the bar for rock guitar technique. It has been reissued many times and in many formats, along with the now equally famous Flex-Able Leftovers bonus tracks. In commemoration of its silver anniversary, Vai is preparing a specially remastered, 25th anniversary deluxe reissue of the album that put him on the map.

Flex-Able was the disc that introduced Steve Vai to the world. Although he had already made several albums with Frank Zappa, Flex-Able was the first record that presented him on his own terms. His uncanny mastery of the fretboard, the strange voodoo he could work with a whammy bar, the soul-searching lyricism of his ballad playing, his compositional flair, even his mystical, tantric alien love god persona—the whole Vai story begins with Flex-Able.

The album is also an important early example of a rock musician seizing control of the means of production and distribution, and having it his own way. Vai recorded it in a home studio that he built with his own hands, and then released it independently. In that respect, Flex-Able is an important harbinger of our own digital D.I.Y. era of MySpace and YouTube, Pro Tools and Garage Band—except that Vai did it all analog, at a time before personal computers had even made their way into most people’s homes and the internet was still more than a decade down the road. Nonetheless, Flex-Able has sold more than 300,000 copies to date. Not bad for music that its creator thought would never sell.

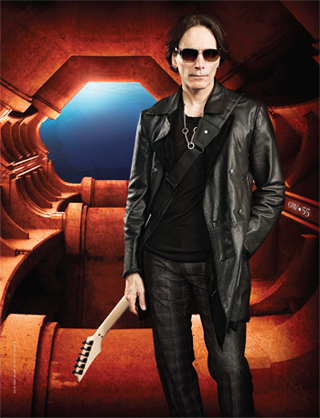

These days Steve Vai is no longer scared to death of fame. Posing in an L.A. photo studio for this month’s Guitar World cover (in which he recreates Flex-Able’s jacket art), Vai is relaxed and assured, completely comfortable in his tall, lanky rock star frame, working the lens with the same easygoing command he exhibits on the fretboard. But he also remains one of the nicest, most unassuming guys in rock, with a kind word for everyone in the room, a joke or a concerned inquiry as to the other person’s well being. Settling into a sofa after the shoot, he seems eager to discuss his plans for the special 25th anniversary reissue of Flex-Able.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“What I’m working on is remastering Flex-Able and Flex-Able Leftovers in their original form, and releasing that, along with a photo book and the whole story of that time in my life,” he explains. “The bonus material includes a whole slew of stuff that was recorded even before Flex-Able, in an earlier home studio I had. It’s some really weird stuff. I say ‘weird,’ but what I really mean is silly. When I listen back to some of it I think, Who the heck was this guy who made this silly stuff?”

That guy was a guitarist in his early twenties from suburban Carle Place, Long Island, who’d been plucked from the Berklee School of Music by none other than Frank Zappa and whisked off to L.A. to serve as Zappa’s music transcriptionist and “stunt guitarist,” the Zappa band member who played the “impossible” guitar parts. The young Mr. Vai also possessed an almost lifelong obsession with audio recording.

“Even when I was a young boy,” he recalls, “besides the guitar itself, the thing that fascinated me most was the idea of recording sound on sound. I started recording stuff the day I started playing guitar. Even today, I record myself playing the guitar at least an hour a day, probably four or five days a week. I just sit and play, and I record it. I don’t even know why. There’s maybe the idea of some kind of posterity, which more and more seems like a big waste of time. But just maybe the idea of going back and listening to the person who I was at that time.”

Vai arrived in Los Angeles on his 20th birthday and set himself up in an apartment at 1435 North Fairfax, where he assembled a little four-track studio he called “Sy Vy.” When he wasn’t working with Zappa, he was in his apartment cutting his own tracks. In the early Eighties, the home recording boom was really getting underway. Tascam and Fostex had begun releasing the first affordable reel-to-reel multitrack tape machines in the late Seventies. The dawn of the Eighties brought the Portastudio concept: four tracks on cassette, with an integrated mixer. Prior to this, musicians without a record contract or other financial means of paying for commercial studio time had no affordable means by which to record their own music. The advent of home studios profoundly affected the evolution of popular music and the music business in the decades that followed.

A few years into Vai’s tenure with Zappa, he’d saved enough money for a down payment on a little house in Sylmar, a remote L.A. suburb. And there, in a backyard tool shed, Vai erected his second studio, Stucco Blue, based around a Fostex eight-track, 1/4-inch reel-to-reel tape machine and a Carvin console. It was here, between April and November of 1983, that Vai recorded the tracks that would become Flex-Able.

“After working on four tracks, moving to eight-track was like, ‘Wow, this is a party!’ ” Vai recalls. “And the first piece I recorded was a song called ‘Chronic Insomnia’ [included on Flex-Able Leftovers]. The tape machine had a vari-speed control—half a step up in pitch and half a step down. I wrote this linear piece of bizarre music, with all these polyrhythms, and I recorded it eight times on each of the eight tracks, each time changing the [tape] speed a little bit. And then I flipped the tape backward. So when you listen to the piece, you get this eight-piece octonal, bizarre piece of music.”

Many of the Flex-Able tracks originated as wild studio experiments or even jokes. Vai brought his friends in on the recordings, along with fellow Zappa band members Chad Wackerman and Bob Harris and bassist Stuart Hamm. Pia Maiocco, soon to be Mrs. Vai, was also in attendance. And because these tracks were basically goofball home recordings, Vai’s initial thought was merely to press up the music on a limited run of flexi discs that he would give to friends. Flexi discs were phonograph records pressed on very thin, flexible sheets of vinyl that were often bound into the pages of music magazines as a free giveaway. The flexi disc idea may well have contributed to the genesis of the album title Flex-Able.

But when printing up the discs proved to be too complicated, Vai decided, reluctantly, to attempt to secure a conventional record contract. He was shocked at what he discovered. Then as now, the standard record deal involves signing away all of your copyrights in return for an upfront advance (generally around $10,000 at that time) and a minuscule royalty of a few cents for each record sold.

“I thought, This is absurd; I’d never sign anything like that,” Vai recounts. “Record labels bank on the fact that artists believe that a record deal is the Holy Grail, so they’re willing to sell their intellectual property very cheaply. But I had no attachment to the idea of being famous or having my record released by a record company. And that gave me the freedom to turn away from that kind of deal without even considering it.”

Instead Vai formed his own label, Akashic Records, and found a distributor, Cliff Cultreri of Important Records, a raving Zappa fan who became Vai’s lifelong friend and ally. The Important distribution deal netted Vai a generous $4.10 per record sold, and Vai retained his copyrights—a dramatically better deal than a conventional record contract. And Flex-Able began to sell. The shred/metal/virtuoso guitar phenomenon was getting underway, and Flex-Able became one of the genre’s cult classics. Starting in the late Seventies, indie records had been a key component of the punk/new wave scene. And now the indie concept was fueling another kind of rock phenomenon.

But Flex-Able’s appeal transcends the Eighties. The album continues to be a solid seller. And as vinyl records gave way to CDs, and Important Records was acquired by Sony, Vai found himself sitting even prettier.

“To this day, Sony distributes Flex-Able, and they have to account to me for $7.50 for every CD sold,” Vai says. “That’s more than they’ve ever paid any artist in history, I’m sure. Because it’s a distribution deal, not a record deal. And I’ve sold, like, 300 to 400 thousand copies of Flex-Able. I’ve made millions of dollars from that little record by retaining my rights. I don’t mean to sound like I’m bragging, but it just goes to show you that it can be done—even with a record as bizarre as that one.”

Vai seems to be in a career-retrospective mode of late. In addition to remastering Flex-Able, he is releasing a new set of discs he calls Naked Tracks. Basically, he’s gone back to the master recordings for all his post Flex-Able solo discs—Passion & Warfare, Sex & Religion, Alien Love Secrets, Fire Garden, Alive in an Ultra World, The Ultra Zone, Real Illusions: Reflections—and stripped away the lead guitar tracks, so that aspiring Steve Vais the world over can play along with the backing tracks. Along with this he has launched VaiTunes, an internet subscription service that will release one previously unreleased Vai track a month culled from the guitarist’s vast vault of studio experiments, soundcheck recordings and so on, along with a five-to-10-minute Alien Guitar Secrets instructional video.

As that weren’t enough, Vai has just released a new concert DVD, Where the Wild Things Are, documenting a stop along his 2007 Sound Theories tour and featuring a stellar band that teams Vai with dueling violinists Alex DePue and Ann Marie Calhoun.

But it all ultimately gets back to Flex-Able, the album that started it all. Some artists look back on their earlier careers with bitterness and regret, but not Vai. For him, Flex-Able was not only the first in a series of smart career moves but also the start of a musical and spiritual quest for the absolute, a journey that has taken him to the highest pinnacles of rock guitar artistry.

GUITAR WORLD What sort of memories, feelings and reflections came up for you in the process of remastering Flex-Able?

STEVE VAI A lot of things come flooding in when I listen to Flex-Able. It was made at a time when life seemed so easy. I was surrounded by friends and people I loved. I was with Pia even back then. I didn’t have a care in the world. I had no expectations of being great or having to survive in the world. We were just basically glorified college students living in a house that I had purchased off my proceeds with Frank Zappa. It was a wayward home for musician refugees. At any time, we’d have nine or 10 people living there. Most people who you know that I know lived in that house at one time or other. It was really, truly a glorious time. We had chickens in the backyard. Right outside my window was a fig tree…all these things come flooding to mind.

GW But why Sylmar, of all places?

VAI Back then Sylmar isn’t like it is today. It was very rural. There was no smog. It’s at the base of the San Gabriel mountains. We would go hiking and camping in the mountains. There was a ranch across the street with horses. It worked out really well that it was far away from L.A. Pia actually found the place. I needed a house that had somewhere I could play music. And this house had a tool shed in the backyard, with two good-sized rooms, built by the previous owner. I spent five months and $5,000—money I earned giving guitar lessons—and I built this studio, Stucco Blue, in that backyard shed. There’s photos of me doing it. I went out, bought the wood, built the studio and put the gear in, entirely by myself.

GW And Frank Zappa contributed some of the studio gear?

VAI If not for Frank’s support—with the equipment he gave me and his encouragement—I never would have made or released Flex-Able. Frank taught me a lot about editing. He taught me how to edit tape with a razor blade. He loaned me the two-track [tape] machine that I mixed down to and that I ended up purchasing from him. He gave me the Linn drum machine I used on the album. And when I gave it back to him I had to go to using a real drummer. Frank gave me compressors, a flanger, phasers…real rack gear. I could never have afforded anything like that at that time.

GW Zappa’s musical influence is also profoundly present on the album, especially on tracks like “Little Green Men” and “Salamanders in the Sun.” I don’t think anyone has ever approximated Frank’s compositional style as effectively as you have.

VAI Frank was my mentor. If I wasn’t in my apartment, or later my house, I was at Frank’s house. He was Frank Zappa and I was this 20-year-old kid. I was naïve, very innocent and completely coarse in my makeup. I had no understanding of culture, really. I was just this kid from Long Island making this crazy music. And I think Frank really got a kick out of it, because he supported me. He was the only one I ever played this stuff for when I was working on it. I played it for him, and for friends who were there.

GW Along with more composition-oriented pieces like “Little Green Men,” Flex-Able also introduces a lot of the extreme guitar acrobatics that would become signature Steve Vai techniques. Something like “The Attitude Song” is almost like a brief synopsis of what was to come in your career.

VAI “The Attitude Song” was originally recorded in Sy Vy Studios on Fairfax Avenue as a demo for Alice Cooper, ’cause I’d heard Alice was looking for a guitar player. The audition tapes were due the next day. So I wrote and recorded “The Attitude Song” in one night, and it was called “The Night Before.” I improvised a bass part, and then I just built the guitars on top of it. And then when I got to Stucco Blue, I rerecorded it.

GW Were the more rock-band-oriented songs on Flex-Able, like “The Attitude Song,” cut live in the studio with the rhythm section? Would you cut a basic track with the drummer and bassist?

VAI No. I could cut a basic track by myself, and then I’d get the drummer in there and tell him what to play. I didn’t rehearse that stuff—it was all built up track by track in the studio. Or at least “The Attitude Song” was. Something like “Viv Woman,” we would just play that together all the time, and then we just threw it down to tape.

GW Your sole guitar for Flex-Able was a Seventies Fender Strat?

VAI A ’77, I think, yeah. I also had a blue guitar made by Performance Guitar, but I’m not sure if I used that one or not.

GW You mention the Fender in the liner notes.

VAI Yeah, that’s probably the one I used. There’s so much material; it’s hard to remember everything.

GW What kind of trem was on that Fender at the time?

VAI That was a Floyd Rose. I had one of the first Floyds. It was a pain in the ass, because it didn’t have the fine tuners. It was before the fine tuners came out.

GW A lot of the extreme trem moves—signature Steve Vai stuff—is already in place on that album.

VAI Yeah it is.

GW Were these techniques you developed with Frank? Earlier?

VAI It was just stuff I imagined. “The Attitude Song” was a reflection of knowing in advance that, if I had a bar, I could do those things. Because what anybody was doing with a bar back then was nothing. I mean Eddie Van Halen was doing dive bombs, Hendrix was doing dive bombs; but as far as playing melodies with harmonics and certain dips inside the melodies, that was inspired by the concept of composition rather than what anybody else was doing. If you listen to “The Attitude Song,” it’s got one time signature against another, and it’s got triple harmonies that move in and out of unison. None of that is accidental. It was a matter of having these compositional ideas and then finding a way to use the bar to execute them.

GW Did you start trying to do this stuff with a standard Fender Strat trem? Or was it the advent of the Floyd that enabled you to even begin doing this?

VAI Yes. There was no way I could have done any of that stuff with a regular trem. You couldn’t get the notes and strings to do what they do without something like a Floyd. And then that ability to pull up on the bar was something that no standard guitar could really do.

GW Were you using any kind of sustainer on any of the Flex-Able recordings? That’s another device that’s central to your unique approach.

VAI No. Sustainers did not exist back then, as far as I know. But one thing I used to do was put the headstock of the guitar on the speaker cabinet while I was playing. The resonation would cause the guitar to vibrate like a…well, like a vibrator.

GW You were already using Carvin amps, another standard item of Steve Vai gear, on Flex-Able. How did you get into them?

VAI You know, when you’re a kid and you see pictures of a guitar, you get wood. You get this inner excitement. When I would see pictures of equipment—like amplifiers and guitars—my heart would actually beat faster. I would sit and stare at them. It was like porn. And then one day, I remember, I wrote away to an address in some magazine for a Carvin catalog. They had these beautiful catalogs where they’d have mountains of amplifiers strewn out on these green pastures. Oh my God, that was like the jackpot, man! I knocked myself out when I got that catalog. So I thought, Carvin…when I move out to California I’m gonna get with them. And Frank was working with Carvin, so I got hooked up with them. And they gave me my first stack. Actually the picture that’s on the cover of Flex-Able was drawn from a photo that was used in the first gear ad I ever did, for the Carvin Legacy X100B amp. And I remember when that stack first arrived, I just sat there and stared at it. I couldn’t believe I actually owned a stack, you know? And I used that on the whole record.

GW You just miked one of the speakers?

VAI One mic, yeah…I didn’t even know how to mike it. I just experimented with different ways. You know, the process of recording Flex-Able was tremendously educational for me, because it was how I learned to engineer recordings. Before that, if I had to hook up a stereo I was scared to death. I couldn’t even connect the ins to the outs and the outs to the ins. And then I had to build this studio from scratch, get the console, plug in the gear and figure out how the signal path worked. I made the best of the equipment I had. I had a 1/4-inch eight-track machine, so you can imagine…

GW Not a lot of real estate there.

VAI No. And in fact, if you look at the master, there are so many [tape edits]. That was because I had to mix little individual pieces of each song one at a time. And that was because I had so many different things on each track. You’d hear a guitar part, followed by a bass, and then maybe a backing vocal…all on one track! That was the only way to fit everything onto the eight tracks I had. So when it came time to mix, I would have to take the verse for “Little Green Men,” for example, mix it over to two-track and then go back and mix the B section separately, because all the settings for the B section would be completely different from the verse because there were completely different instruments on the tracks. And there was no [console] automation. None of that. So I’d mix each section separately down to two-track and then edit the two-track sections together. If you look at the master tape for the entire record there are hundreds and hundreds of edits. It took forever.

But the biggest education was learning how to place things within the stereo spectrum and the frequency spectrum: panning and EQ. It’s almost like a Rubik’s Cube. You can’t put certain sounds in the same place as a cymbal, because it’s the same frequency and if you put that over there it’s gonna cause phase cancellation. Realizing that stuff had a big effect on me. I had this big stereo UREI EQ and that’s where I learned where frequencies were. I realized, If you take 10 kilohertz and move it over here, that’s what 10k sounds like. This is what 1.2k sounds like, and this is what 100Hz sounds like. So if you listen to Flex-Able, it’s very well distributed EQwise. And that really helped me later on when I went in to make Passion & Warfare, because that record was a lot more dense: bigger guitars that were hogging the stereo spectrum. You put that on top of the biggest drum sound ever and it can be a disaster if things aren’t placed exactly right. So if I hadn’t spent all that time mixing Flex-Able, Passion & Warfare would have just been a mess.

GW It sounds like the guitar’s going through an envelope follower on a few tunes from Flex-Able, like “Lovers Are Crazy” and “Call It Sleep.” Is that one of the old Electro-Harmonix Dr. Qs?

VAI It was a Mu-Tron Bi-Phase. I bought a box of gear from somebody at a garage sale, and it had a Mu-Tron Bi-Phase and something else by Mu-Tron, along with one of those Maestro phasers, which I loved. There were also a couple of other little stomp boxes that I just put everything through.

GW Along with introducing a lot of your signature sounds and guitar techniques, Flex-Able also introduced the element of mysticism that’s in a lot of your work. “Salamanders in the Sun” is dedicated to the Hindu deity Saraswati, who looks after all of us poor musicians and writers. And the name of the record label you created to release Flex-Able is Akashic Records, which is another reference to mystical tradition. The Akashic record is the repository of our past life information, kind of the karmic fingerprint file.

VAI Oh, everything I did back then was a reference to mysticism and metaphysics! Through my whole life, I’ve always been a seeker. And the recording of Flex-Able marked a kind of turning point for me. Because right before then, when I was 20 and living on Fairfax, I went through a really dark depression. I don’t know why really. It happens to people. But it was a very, very dark night of the soul. And right around that time I started going to a great metaphysical bookstore in West Hollywood called the Bodhi Tree. I used to live in there! I would go in there and read all kinds of stuff. I’m a very practical person. I can only understand things that make sense to me. From a very early age, I understood that science is limited by human intelligence. I grew up as a Catholic, but all of that didn’t make sense to me at all. But when I was exposed to the Bodhi Tree and all these different Eastern and mystical philosophies, there were these core principles that started to emerge. And those were the things that started to make sense to me and pull me out of this black hole. And when I moved to Sylmar, built the studio and started Flex-Able, that was really the awakening of my leaving behind that very dark state of mind. And that’s reflected on the album too. That’s why, when I listen to it, I just hear a young man going through a cathartic mental change in life. But I’d like to emphasize that now I feel deeply in my heart that I’m a completely happy and fulfilled person.

GW Flex-Able also introduces the alien/extraterrestrial persona that would become another key element of the Steve Vai mythology. Do you really believe that there are other life forms out there?

VAI Well, I think it’s extraordinarily arrogant to believe we’re the only living or intelligent creates in the universe. But back then, as I say, I was researching a lot of things. And I got into UFOlogy. When I was much younger, I used to go to this store called UFO News in New York City. In those days you had to call in advance to make an appointment. You get there, they check you out, and you go in. So at my house I still have these rare UFOlogy papers: “How to Build a Spacecraft.” Really! All this stuff about gravity and antigravity, the Philadelphia Experiment [an alleged 1943 U.S. naval military experiment in which a ship was to be rendered invisible] and the Hollow Earth [the belief that Earth has a hollow, habitable interior]—all this really fun, fascinating stuff. I was really curious about it at one point. And it’s not unlikely to me that some of this stuff is real, if not all of it. One of the things that actually makes some sense to me is the idea of interdimensional beings.

But as I started to prioritize my spiritual goals I realized that, even if aliens exist, they still have to answer the same basic question that humans do: Why are we here? Why do we exist? And we each take that journey alone. So all that stuff—extraterrestials, UFOlogy, seances, mediums, numerology, reading the stars—I don’t discount that it exists. But I went through that stuff and it now resonates at a very low level for me, spiritually. In fact, it’s a deterrent, because you get lost in that stuff and lose sight of the real goal. I just think that the thing an alien would have to discover is the same thing we humans have to discover—which is what some spiritually advanced people have always known. And they all say the same thing: the creator and the whole creation is in the core of the human consciousness. And you have to figure out how to get there. That makes sense to me. There’s no alien that can tell me anything different that’s gonna make more sense. Where I want to go is way beyond that alien stuff. But because I wrote a song called “Little Green Men”—which was a piss-take of that whole UFO movement, basically—that whole alien thing kind of stuck with me. There are people who literally believe I’m an alien!

GW Yeah, there probably are. Do you have weird fan experiences?

VAI Through the years, I’ve seen everything. In fact I just had a message on the phone yesterday from the F.B.I. who need to investigate some bizarre stuff that’s going on with a fan. It’s just part of the territory. Yes, there are people who actually believe I’m an alien, but that’s not a product of me. That’s a product of their mind.

GW So for the edification of those people, you’re not an alien. But have you ever seen a UFO or been abducted?

VAI Not that I know of. The last time I received any kind of anal probe, it had a rubber glove on it and charged me $900 for the privilege. I didn’t even get a walk along the beach after it.

GW Rather than an alien, I tend to think of you as being more like a monk or yogi in your absolute devotion to the guitar. It takes an incredible amount of discipline to perfect the kind of guitar techniques that you’ve brought to rock music.

VAI But when you love what you’re doing, there’s no discipline involved. I was in pain when I wasn’t sitting for hours playing. When I look back, when I was younger, I wasn’t very bright in school, really. There was nothing special about me. And I had some issues in my life, and perhaps those things made me gravitate toward being very intense about one particular thing: the guitar. Maybe it was an escape. My desire to play so much and be so into it—I don’t necessarily say was a healthy desire, because nothing else mattered to me. When I was younger and playing the guitar I didn’t really care about anything else. It was a selfish frame of mind really. All through Flex-Able and Passion & Warfare, my addiction to being a workaholic was a very selfish thing. But I did understand, through all my work ethics, the importance of balance in life, and how to become a good time manager.

I gotta tell ya, I never struggled a day in my life with my instrument. And I never struggled with my career. I always had more than I could use. I’ve achieved much more than I ever expected to. If everything stopped now, I’d say, “Nice run. More than I ever expected.” But having said all that, I still love doing it. I want to continue and have a lot more plans. But if I had to put it in a nutshell, I just love playing the guitar. And every time I was able to play something new and different that I didn’t hear anywhere else out there, I would jump for joy. The guitar, for some reason, was always beautiful to me. It was enigmatic. It was gorgeous. It was this untouchable, beautiful piece of loveliness. It was this gateway to freedom. Playing the guitar every day is still an honor, a privilege and a joy.