Taj Mahal and Ry Cooder on reuniting after nearly 60 years to pay tribute to blues legends Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry

Get On Board finds two old friends and collaborators back in the studio for an album of Piedmont blues covers that might just happen to be their finest hour on record

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Talk to any dyed-in-the-wool fan of blues music and it won’t be long before they mention Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry. Hailing from Tennessee, guitarist Brownie McGhee learned his craft from Blind Boy Fuller.

But it was when he paired up with blues harp wizard Sonny Terry that he found his perfect foil – and the duo were lionized by the folk scene of '60s America.

Around that time, a young Santa Monica guitarist, Ry Cooder, stumbled across their records in a secondhand record store. After that, he sought out live performances by McGhee and Terry, learning licks directly from McGhee after the shows.

Meanwhile, another aspiring blues-folk artist, Taj Mahal, was piecing together where he might witness the music of a duo he had heard fragments of over the late-night airwaves. Like Ry, he couldn’t believe McGhee and Terry weren’t major stars. And – again, like Ry – he found that their live performances were a wellspring of pure musical joy.

Weaving together strands of blues and folk, their music defied easy categorization – which is, in itself, reflective of the underlying reality of the music of America’s South. Eclectic, entertaining and wide-ranging, it was a huge influence on Cooder and Mahal.

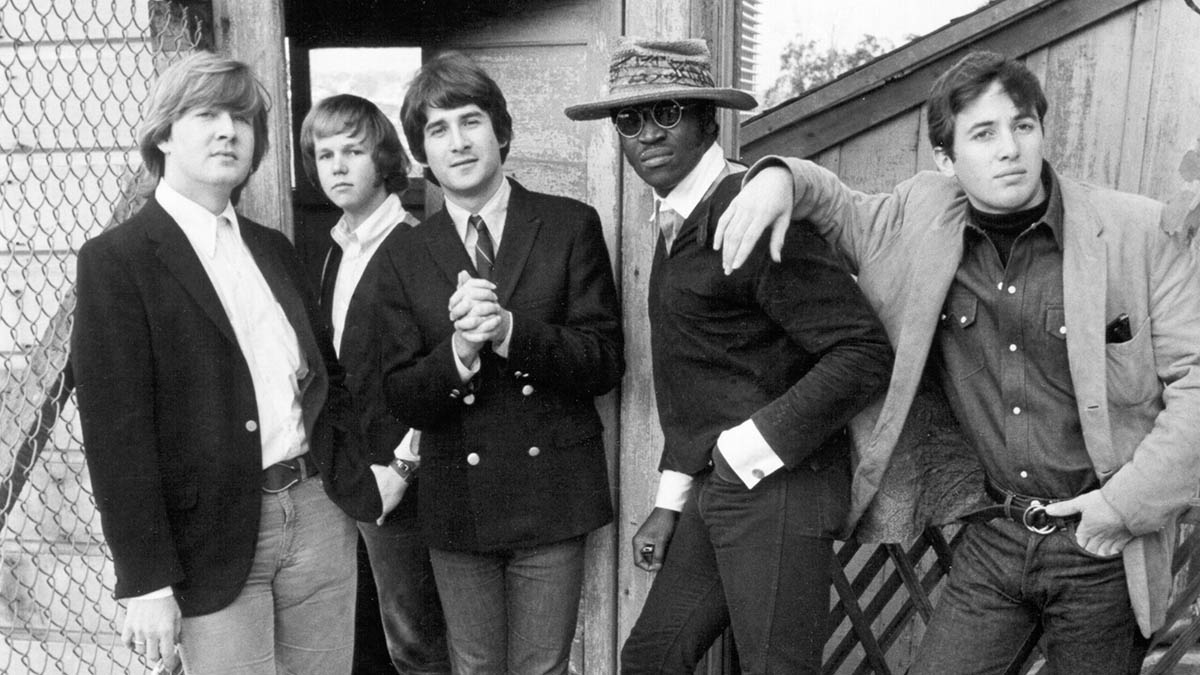

The latter moved to Santa Monica in the 1960s and met Ry – and Ry played on Mahal’s eponymous debut album in 1968. Now, nearly six decades later, they have reunited to record Get On Board, a captivating tribute to the music of Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry.

We joined these two past-masters of American music to discover why returning to their roots yielded one of the best recordings of their career, and learn why a guitar so large that Ry could barely get his arm around it was the star of the show…

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

When did you first encounter the music of Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee?

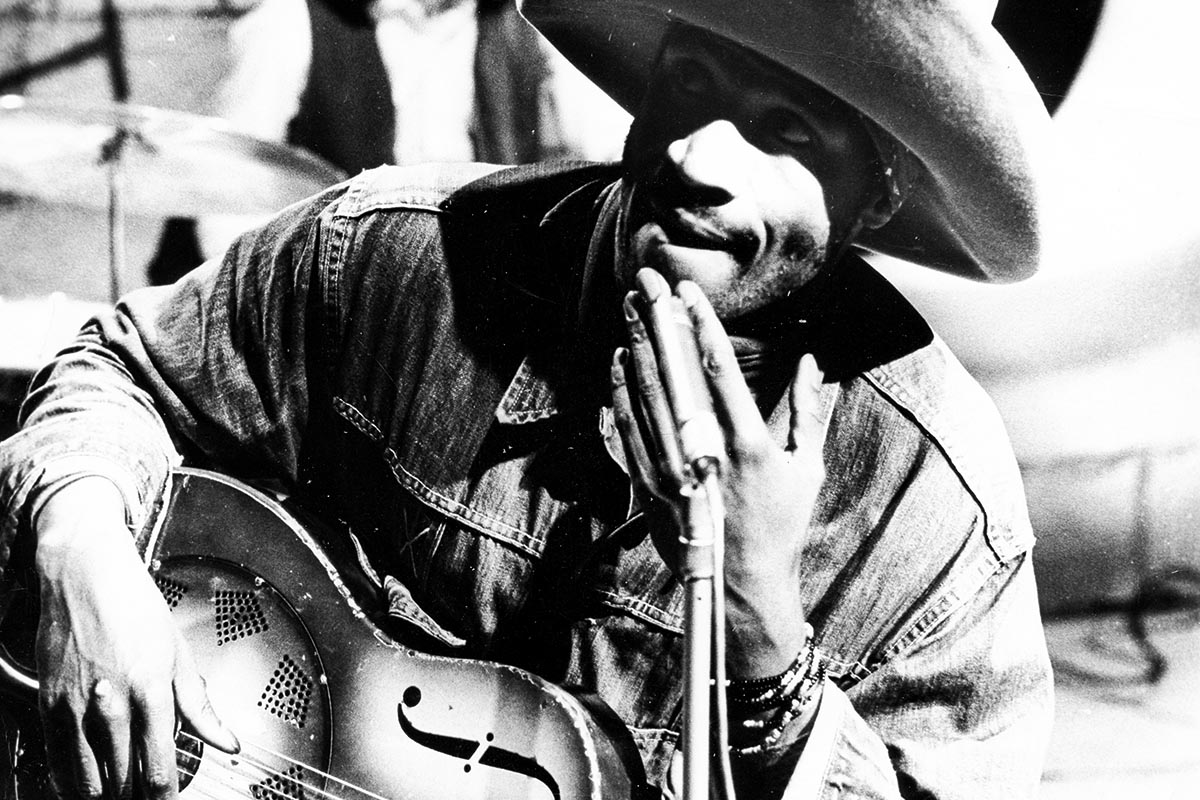

Taj Mahal: “Well, I started hearing them probably when I was 15 or 16 years old. You’d hear little bits and snatches of them on the radio and whatnot. Not on regular radio – but some late-night blues program would be on and you’d hear it and be struck by how good it was. And then I just wondered where these people were.

“But later I came to university, during the 60s, when the whole folk-craze came through. And many of these musicians, people like Brownie and Sonny and Bukka White, Mississippi John Hurt, Sleepy John Estes and others, were being brought around to coffeehouses and played at folk festivals. So I began to realize that there was a place you could go and see them play, you know?

“I got to see them and I thought they were just incredible. And I hoped that I would be able to be that good someday. I mean, I could play a little bit and I could sing quite well, but I was just learning to get my guitar chops together. But Brownie was really good and Sonny was just a wizard on the harmonica.

“Those guys, they’d play with Lead Belly, they’d play with Pete Seeger, they’d play with Blind Boy Fuller or the Reverend Gary Davis… they had some versatility, to be honest. They were involved in different plays on Broadway, like Finian’s Rainbow, and came up with some great stuff.

“I mean, that whole Fox Chase blues stuff that Sonny Terry came up with – that’s a Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina style. I never saw them put on a bad show. Ever.”

Why do you think history has remembered Robert Johnson and BB King, for example, but only hardcore blues fans tend to know about Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry?

Taj: “Well, I don’t even think that everybody knows the aforementioned people you’re talking about. In fact, I’d never heard Dust My Broom [by Elmore James], none of that, until I came to the university. I was about 19 years old and they put out Robert Johnson's King Of The Delta Blues Singers. I was like, ‘Who is this guy I’ve never heard of before?’

“Why, all of a sudden, was this whole group of folkies going, ‘Wow, wow, wow – listen to this guy play…’? I had absolutely no idea! So I put the record on and at first it sounded [quick]. And the reason was they had printed the record at too fast an rpm. But when they finally got it at the right speed, it really made more sense.

“But still, [I had] never heard of Robert Johnson before that. Now, John Lee Hooker I had heard of. BB King I’d heard about. And maybe now and then I would hear that sound when I’d be at a neighbor's house… their moms and pops were in the kitchen and maybe BB King would be on in the background.

“But I’d never heard Elmore James or even understood the sound of slide guitar, except that it was on a couple of Jimmy Reed records I knew. But a lot of that comes from the record-selling industry – they were always trying to put music in boxes. You know, like, ‘This is this kind of blues, this kind of country & western, this kind of pop,’ separating things like that. Oftentimes, the listener didn’t get a chance to realize that [music] was just one big river full of lots of different fish.”

How did the idea of working together again start?

Taj: “Well, we literally hadn’t played together for over 50 years and I was getting a lifetime achievement award in Nashville at the Ryman Auditorium, which is the Mother Church of Country Music.

“Ry and his son were involved in the band, as well as Buddy Miller and Don Was, and so Ry reached out to me and said, ‘What material do you think you’d like to do?’ I suggested maybe something that was a little more country.

“He said, ‘Oh, well, I mean, that’s all right, but I think we should pump it.’ And I was like, ‘Okay, I do, too – but I was trying to be a little diplomatic.’ So I said, ‘Well, that only means only one thing, Ry – Statesboro Blues.’ He says, ‘You’re on,’ and so we did a version, which is now on YouTube.

“Little by little, we started communicating with one another again. We started sending music back and forth and, at one point, he came and he said, ‘Well, what do you think about this? I’ve got an idea. Why don’t we do a tribute to Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry?’

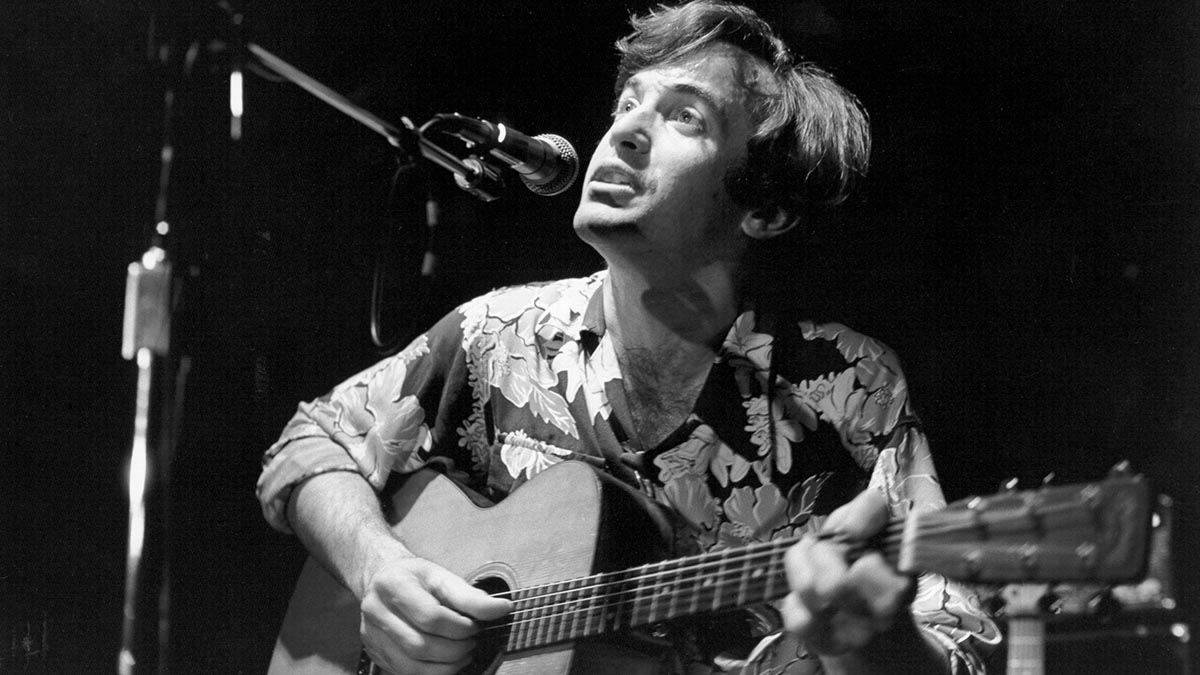

“Well, I was ready right there [laughs]. I came down to Los Angeles and we played together again and it was just great. We had lots of rapport, lots of communication and it took off from there. The way we recorded, it was kind of a back porch-y, living room style, you know? Real music, live music… the way it is.

“Ry set the music up and then we got to playing and we’re talking to one another. That’s what you really want to happen is that, ultimately: you’re speaking to one another through the instruments.”

How did the sessions for Get On Board go down?

Ry Cooder: “Well, [my son] Joachim’s got this nice old Spanish-style California house down the street from us here. We’re in an old neighborhood – we’re not in LA any more. We’re all out in this other area.

“His living room is about the shape of what you might expect in an early recording studio with a very high ceiling, wood floor and some plaster as well. The architect that designed the house was a very good architect.

“I happen to know who it was – and at the time, in 1927, he came upon this shape of this room somehow, and he thought it would be pleasing. But maybe he didn’t know that it’s also acoustically perfect, as long as you don’t play too loud. You can’t hit a loud snare drum in there and you can’t play electric bass in there. But you can do all kinds of things acoustically.

“Then [there was] our engineer friend Martin Pradler – to say he’s a genius is like saying Beethoven was a pretty good orchestrator. I mean, he’s a tremendous interpreter of how the music should be recorded and we’ve worked with him for a lot of years now.

“So I said to him, ‘Martin, I’m going to play acoustic guitar, which I hardly ever do in recording, and Taj is going to play harmonica. We’re going to sing. It’s all live and Joachim bangs on these strange oddball drums. And we’re going to sort of be in a triangle.

“'The drums a little further away from the vocal mic, but it’s a good‑sized room and we want to mic the room… don’t mic us too close. We want it so it sounds like you walked into a place like a little juke joint or a little bar or somewhere where you hear the thing [as a whole], not as isolated individuals…’

“So he set the mics up. Tube mics, naturally. We’ve got all this old equipment – me and Martin between the two of us – that’s really good. But, the point is, it’s period equipment. It’s vintage but good. We record through an old AM radio tube-powered board [desk] and he moves mics around until you hear in the earphones, ‘Ah, that’s the spot for that mic.’

If you like the sound, you can record anything. If you don’t like it, you might as well go home

Ry Cooder

“You know, that’s capturing something that’s well defined, but it’s ambient – like being in the room. That’s what I want. When I hear it, I’ll like it. And when we like what we hear through the earphones, then we can go ahead and play and we don’t have to work too hard. It’s very natural. If you like the sound, you can record anything, you can play anything. If you don’t like the sound, you might as well go home.

“I overdubbed stuff here and there, but the basic tracks with the live singing is what you’re hearing. Yes, I added bottleneck here and there and whatnot, and maybe another harmony sometimes because it’s nice to hear three voices just for fun. Nothing fancy but just to get the groove going right. If the groove is right, you’re in business with that music. That’s really what it is. Who cares what the lyrics say so much? They’re fun lyrics, but the point is the groove, you know?”

The acoustic sounds on Pawn Shop Blues are incredible. What guitar did you use for that?

Cooder: “That one there is one of these Banner [logo] Gibsons J-45s. I think it’s from 1943. But I like to vary things. The real oddball guitar, the crazy guitar, was on the track [What A] Beautiful City. It’s the most goddamnedest thing you’ve ever seen. It’s an Adams Brothers guitar that’s so big. It’s as big as a guitarrón, and I can barely hold it and wrap my arm around it.

“It’s enormous and it has a short neck, so it can only be played in one key, E. But it has this incredible sound. 1905 it was made, and how it survived all these years, who the hell knows. That’s a wonderful guitar.

“But that J-45 on Pawn Shop Blues is nice, yeah. It’s not as resonant as the [Martin] D-18. I used the D-18 for most of the tunes because that’s what Brownie played. For that music it’s perfect: very big, twangy sound. But for Pawn Shop Blues I needed something a little quieter and played a little softer, so that Banner J-45 is nice – it was in a fire, I think, so it’s real damaged [laughs]. It looks like somebody in Pompeii had it when the volcano erupted, but it’s good.”

Taj: “Ry also had a cello banjo. The [pre-war] instrument makers made violins, viola, cello. And they made banjos like that, too – bass banjos, mandolas, mandocellos or banjolins. That was the imprint from the European instruments when they came over here and started to make them. Ry had some extraordinary ones… I had a steel guitar, a wooden guitar and a plethora of harmonicas.”

Pawn Shop Blues has a really slow, meditative tempo that gives it huge emotional weight. You don’t hear that so much any more in blues. Why?

Cooder: “First of all, everybody’s moving too fast. If you don’t think so, just go on to LA freeway sometime. People move too fast or they’re in a hurry all the time, like, ‘I get my brown shoes – no socks – I get my tattoos, I get my beard and my hat and my little box-back coat. And then I’ll get my guitar and then I’ll make my record and then I’ll be famous.'

“And that’s the order of battle, that’s how it’s going to play out. Well, that’s ridiculous. There’s no way that can work. I mean, we older people know that – but it’s basic. So it does take some time.

If you’re going to play real slow, then you have to go into that song as a meditation. Think about nothing and just play the goddamn song

Ry Cooder

“The other thing is, if you’re going to play real slow, then you have to go into that song as a meditation. I mean, shall I use that word?

“You have to immerse yourself in it. You have to have the ability… the desire is very important, but stop thinking about ‘brown shoes, no socks, beards and tattoos’. Think about nothing and just play the goddamn song. Can you evoke something? Can you make it felt? If you feel it, your audience will feel it. And yet at the same time, you have to have enough ability.

“By the way, it’s taken me a lifetime since I started guitar when I was four or so. It’s not something you learn overnight. I’m well aware records exist that show us there were people who were very young, such as Louis Armstrong, who had an epiphany and they became who they became suddenly.

“So that can happen – but not me. I’m a slow learner. So now I’m playing the way I wanted to play when I was young. I actually can hear that I’m doing it, and I can say to myself, ‘This is exactly what I aspired to do all those years ago.’

I’m playing the way I wanted to play when I was young. I actually can hear that I’m doing it, and I can say to myself, ‘This is exactly what I aspired to do all those years ago.’

Ry Cooder

“I remember one time, Terry Melcher, the record producer, said to me – and I was in my 20s at the time or even younger – ‘The rate you’re going, it’s going to take you 20 years to get anywhere.’ And I thought, ‘Jeez, that’s harsh.’ But it wasn’t. He was actually way off the mark: 20, hell! 40, 50 years, maybe.

“You have to realize I’m not from some little podunk town in the South with uncles to teach me. In Santa Monica, there’s no uncles! You’re just on your own. I mean, if you can get anywhere and not have to become an insurance underwriter or an auto mechanic… I mean, they should have taught me auto mechanics when I was in high school, but they didn’t. So I went on and learned guitar [laughs].”

- Get On Board is out now via Nonesuch.

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.