The Who: Not F-F-F-Fade Away

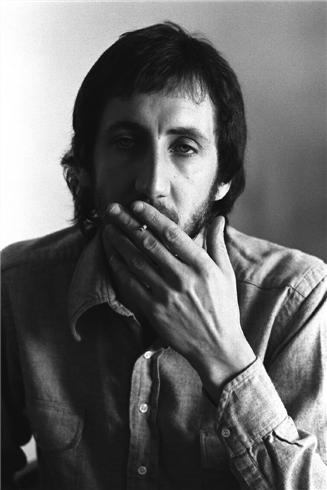

They smashed their instruments, broke musical barriers and composed some of rock’s most powerful anthems. Guitar World looks at 45 years of the Who, and their brilliant guitarist Pete Townshend.

Those who think of the Who as a bunch of old stadium rockers with graying beards must try to realize that they were verydifferent in 1967. They were on the cusp of psychedelia then—four ultra-foppish swinging London dandies looking slightly stunned to find themselves staring out into America’s armpit. That’s how I first beheld them, from the lip of a plywood stage at the grubby Commack Arena in Long Island, New York. The Who had never played anywhere in the United States before 1967. So it seemed nothing short of miraculous that they’d actually come to perform in a shithole suburban town—my shithole suburban town.

The speedy, bruising rock and roll they played that night offered a stark contrast to their ruffled shirts and Pete Townshend’s sequined coat. By ’67, the Who had already evolved into an incredibly intense live band—a powerful, yet graceful, juggernaut fueled by the psychotic combustion of four conflicting personalities. Keith Moon wasn’t a fat drunk back then, but an unbelievably flashy young drummer, just barely out of his teens and enthroned behind his fabled “Pictures of Lily” drum kit—all Union Jacks and Victorian nudes and psychedelic colors.

Roger Daltrey was genuinely frightening. When he wasn’t spitting angry lyrics or twirling the microphone cord high out over the audience, he’d be brandishing a cymbal stand to ward off the town greasers, who’d come to the hall to beat the hell out of one another and hurl cherry bombs at the band. If anyone wanted trouble, Daltrey looked ready to show them that a street kid from Shepherd’s Bush—even one in a frilly ruff—was a damn sight rougher than any little suburban toughies.

Between songs, Townshend played the nice guy: “Oh no, Mr. Officer, it’s your job to tell them not to climb on the stage. I couldn’t possibly. You see, they wouldn’t like our group then. And they might not buy our records…” But after each frail witticism, the guitarist would kick off another tune with a violent windmill, convulsively propelling his body back into his Marshall stack like some self-abusive lunatic. In direct opposition, the only movement from John Entwistle’s side of the stage came from the bassist’s plectrum and fleet fingers. The Ox stood stolidly, even as some teenage girls right behind me threw bits of paper at him all night.

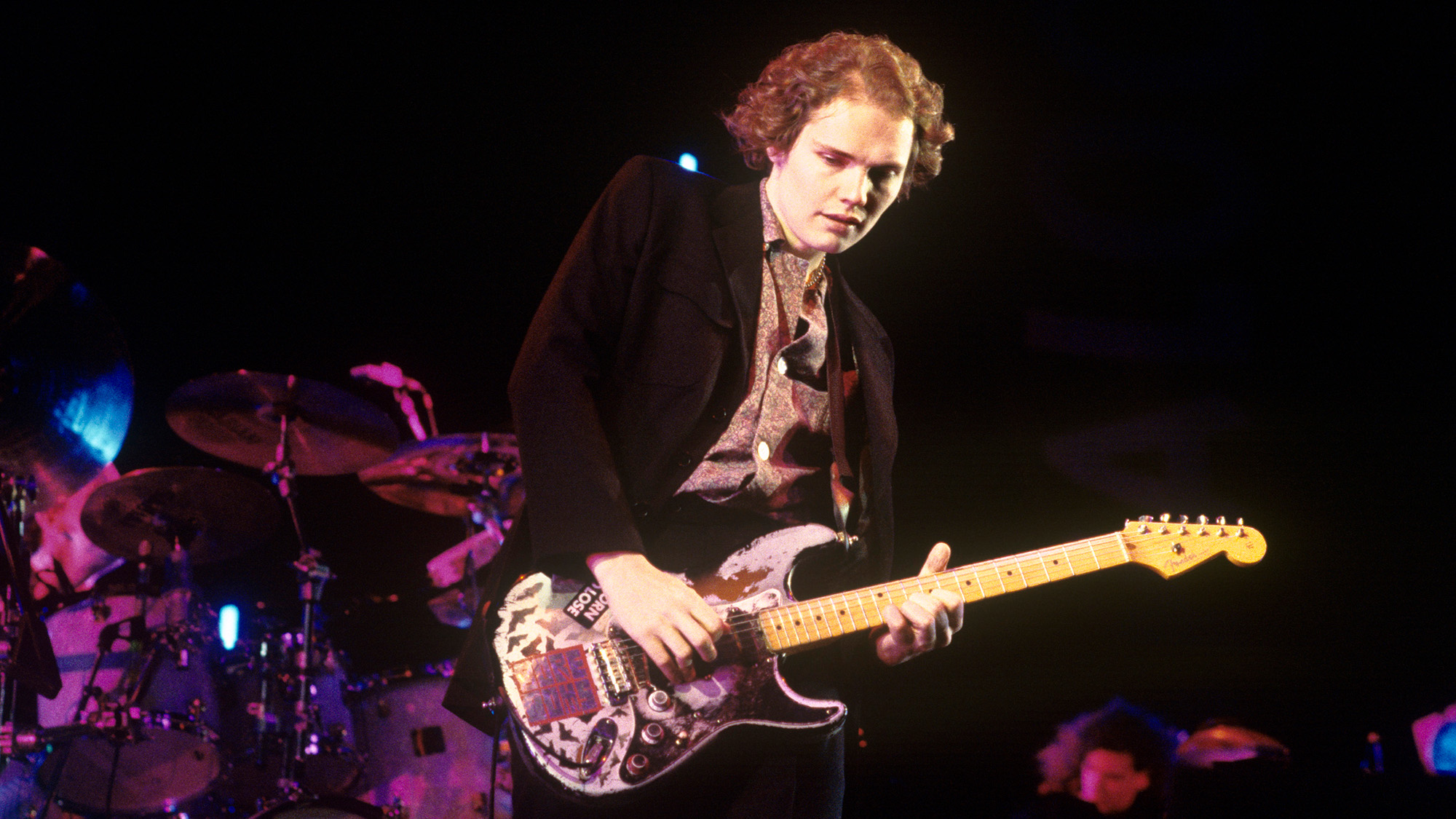

Then, at the climax of the set, came the moment my friends and I had read about in teen mags but dared not think we would actually witness. Pete Townshend slipped the strap of his beautiful Lake Placid Blue Fender Stratocaster off his shoulder and proceeded to slam it onto the stage, repeatedly, violently, strap peg downward, gripping the dual cutaway horns with his long, slender hands. My face was just inches from the stage, so I could feel each resounding impact. The instrument squealed in pain each time it was struck. Feedback. The Strat started to splinter. Pete grabbed the neck and began destroying the guitar in earnest, slamming it against every available surface: speaker cabinets, drums, mic stands, stage…

After that evening, I joined the small coterie of New York Who crazies who followed the band from gig to gig around the Metropolitan area. The Fillmore East Central Park, Westbury Music Fair, the Singer Bowl—we were there. In those days you could pay $3.50 at the door and get right up front to see the Who. Nobody knew who the fuck they were—except we New York Who crazies. It’s hard to fathom this now, but from 1965 to 1969 the Who were an obscure cult band in America. Much as people would later do with indie punk rock singles, we avidly sought out then-little-known Who 45s like “I Can’t Explain,” “Substitute,” “I’m a Boy” and “Pictures of Lily.” These jolting three-minute doses of pure rock euphoria were perfect encapsulations of our young, awkward, angry and lower-middle-class experience.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

The Who were not just another rock band. And Pete Townshend was never your run-of-the-mill guitar hero. Without Townshend, the terms “power chord,” “Marshall stack” and “feedback” might never have entered the modern guitarist’s vocabulary. Instrumentally speaking, the Who were the first power trio, and Townshend defined what the electric guitar could do within that context. But he was never one to riff on mere notes. The guy riffs on ideas—ideas which have profoundly affected the way rock music is performed and presented. He increased rock’s vocabulary a hundredfold, dramatically expanding what can be said with a song, a show or an album.

This year is the Who’s 30th anniversary. If you’re a brand new rock fan wondering what the excitement was all about, MCA’s soon-to-be-released box set, The Who: Maximum R&B, is a good place to start. It must be said that, in the end, any recording is just a substitute for the completely cathartic experience of seeing the Who live.

Wish you could’ve been there.

BACK NUMBERS

The story starts out much like any rock band’s history. Peter Dennis Blandford Townshend and John Alec Entwistle met at Acton County Grammar School in west London. In 1959, when both were around 14, they formed a trad jazz band called the Confederates (bad, or traditional American Dixieland jazz, was popular in Britain during the late Fifties and early Sixties); Pete played banjo and John was on trumpet. Pete came from a musical family. His father was a well-known sax player in Britain and his mother a big band vocalist. But it was John who was the more accomplished musician, a fact that was to have an important bearing on the way the Who’s sound ultimately developed. By the time he started rehearsing with Pete, John had won all sorts of school prizes and community honors for his brass playing.

“When [the Confederates] asked me to join them, I had to run out and get a chord book,” Pete told his friend and biographer Richard Barnes for the latter’s essential Who bio, Maximum R&B. “As I’d been buggering about playing guitar for nearly two years, I wasn’t getting anywhere. They expected me to play and were fairly impressed, which I couldn’t work out. Perhaps they thought that if you could play three chords you could play the rest.”

Pete started out on a very cheap acoustic he’d received from his grandmother. In his last year at Acton Grammar he got something a little better: a £3 special from Czechoslovakia. By this point, Entwistle had added bass guitar to his instrumental repertoire. He and Townshend started a Shadows-influenced rock band that they first called the Aristocrats and then the Scorpions (thus pre-figuring both German rock history and John’s “spider thing.”)

Shortly thereafter, Roger Daltrey moved to Pete and John’s neighborhood from nearby Shepherd’s Bush and lured Entwistle into his own band, the Detours. By all accounts, Daltrey was quite a go-getter in those days—energetic, ambitious, ready to make a point with his fists when verbal persuasion failed. Townshend soon joined the Detours, too—enticed, it is said, by the group’s possession of a real Vox amp. Roger Daltrey was the Detours’ lead guitarist at first, but eventually decided to concentrate solely on vocals. Drummers came and went, until a fateful Thursday evening in March of 1964 when a lunatic from a local surf band dressed in ginger from head to toe sat in on “Roadrunner” during a gig at the Oldfield Hotel. He managed to break the hi-hat and bass drum pedal, thus establishing himself as the man who’d been put on earth to play drums for Townshend, Entwistle and Daltrey. Keith Moon had arrived.

By this point Townshend had already begun attending Ealing Art School, where he was exposed to and eagerly absorbed bohemianism, marijuana, pop art, avant garde music, and obscure American blues, r&b and jazz records. It was one of Pete’s art school friends, the aforementioned Richard Barnes, who came up with the Detours’ new name—the Who—during a hemp-fueled brainstorming session at the flat he and Pete shared. As the Who, the group started to become the musical choice of London’s Mod movement. They played the current r&b and Tamla/Motown songs which, along with Jamaican ska, were the mainstays of the Mods’ musical diet. For a brief period they were managed by Mod pacesetter Pete Meaden, who changed the group’s name to the High Numbers (“number” being slang for a regular street kid kind of Mod, a humble foot soldier in the great Mod army). Under Meaden’s aegis, they made their first single: “I’m the Face”/“Zoot Suit.” The sides—reworkings of familiar blues riffs with Mod buzzword lyrics penned by Meaden—didn’t sell too well. Meaden was dropped and the band name reverted to the Who.

During this period, circa 1964, many key elements of the Who’s approach to the guitar fell into place. It was John Entwistle who first bought one of the new 4x12, closed-back speaker cabinets that London music store owner Jim Marshall had begun to manufacture. The Marshall cabinet gave John such a boost in volume that Pete was compelled to get one as well. And from there, it was just a short step to Townshend’s pioneering use of feedback. It was at the Oldfield Hotel, where the band had first discovered Keith Moon, that Townshend made an equally momentous discovery.

“Where I stood on the stage was a piano, and I stuck my cabinet on it and it was dead level with the guitar,” he explained to Barnes. “And I started to get these feedback effects that I really liked. When I went to other gigs and put the speakers on the floor, it wouldn’t happen. So I started to put it up on a chair and then I decided to stack the things so that I could induce feedback.”

Thus was born the Marshall stack. Equally essential to Townshend’s developing style were the Rickenbacker guitars he had started playing. He’d admired them ever since he saw the Beatles using them. But he soon began adapting the Rick’s eccentricities to his own musical needs. “The strings are closely spaced on a narrow neck,” Pete explained to Rickenbacker historian Richard R. Smith. “The fingerboard is lightweight but superbly balanced. This suited my chordal style, and I invented several new chord shapes using that neck which have since become standard rock shapes. What falls under the fingers on a Rick might dislocate your hand on an old acoustic Martin. The lightweight neck allowed me to produce vibrato techniques by moving the neck backwards and forwards. This became another characteristic of my style. The weak points of the [Rickenbacker] guitars were that the necks would literally break off in my hand if I went too far.”

That fateful weak spot, however, was to change rock history forever. Townshend’s menacing, strident feedback squeals must have seemed shocking enough to compulsively polite Britons out for a few nice pints after a hard day at the gasworks. They’d certainly never heard anything like that before. Nobody on earth had, for that matter. But imagine how badly it must have startled them to see a young lad wantonly smashing a perfectly good electric guitar—one that for many audience members was clearly worth at least several week’s wages.

Townshend was just as surprised as his spectators as he performed the first guitar smashing in history, at the Railway Hotel in London. It was a venue with a particularly high stage and correspondingly low ceiling.

“I started to knock the guitar about a lot, hitting it on the amps to get banging noises and things like that, and it started to crack,” Pete told Barnes. “It banged against the ceiling and smashed a hole in the plaster, and the guitar head actually poked through the ceiling. When I brought it out, the top of the neck was left behind. I couldn’t believe what had happened. There were a couple of people from art school I knew at the front of the stage and they were laughing their heads off. One of them was literally rolling about on the floor, laughing, and his girlfriend was kind of looking at me, smirking. So I just got really angry and got what was left of the guitar and smashed it to smithereens. About a month earlier I’d managed to scrape together enough money for a 12-string Rickenbacker, which I only used on two or three numbers. It was lying at the side of the stage, so I just picked it up, plugged it in and carried on playing as if I’d meant to [smash the other guitar].”

The guitar smashing thing was completely emblematic of Mod culture, with its celebration of fast-paced consumerism and glib disposability. The serious Mod had to discard and replace costly items of clothing on a weekly basis in order to keep up with small-but-crucial changes in the vogue for lapel widths, pocket stitching, fabric patterns, etc. Tiny sartorial details like these made or broke the aspiring Mod. And the ones who did make it often found themselves extremely broke as a result. But here was this bloke in a pop group who not only spent £60 a week or clothes (so the legend went), but who also went through expensive electric guitars like they were pocket squares. With his art school training and his gift for eminently quotable interviews, Townshend was quick to align his Rickenbacker wreckings with the Auto-Deconstructionist movement in contemporary art. Along with Pete’s windmill guitar strum and the Bird Man—a stage pose which saw the guitarist stand stock still with his limbs extended while feedback from his instrument swelled cataclysmically—the Who’s equipment destruction became part of a compelling stage act that netted them the title “World’s Most Exciting Teenage Group” in the mid Sixties.

Of course, the Who couldn’t afford the guitar smashing ritual that quickly became expected of them. It actually kept them constantly on the verge of total bankruptcy, up until the massive success of Tommy in 1969. And that is the essence of the Who’s entire career: They acted out our wildest fantasies, living dangerously, irresponsibly and beyond all known laws. And then they had to foot the bill.

ON THE RECORD

In early 1965, however, things were looking up. The Who’s new management, Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp, secured a record deal for the band and hooked them up with expatriate American record producer Shel Talmy, who’d just taken the Kinks to the top of the charts. “I Can’t Explain,” the Who’s first single, came out in January of ’65 and climbed to Number Eight in Britain. The tune was penned by Pete, who’d set up a recording studio at his loft in Ealing Common and had begun to experiment with songwriting. With its slashing, chordal guitar riff, “I Can’t Explain” owes an obvious debt to the Kinks’ “You Really Got Me,” but the glassy roundness of Townshend’s Rickenbacker tone makes the riff distinctly and unmistakably Who. (Talmy’s number one session jobsworth, Jimmy Page, was also present, but the story is that Townshend refused to lend Page his Rick 12-string. So all the 12-string parts on “I Can’t Explain”—i.e., the song’s principal guitar parts—are generally attributed to Townshend.)

It’s often been noted, however, that the real lead instrumentalist on “I Can’t Explain” is Keith Moon, whose terse, belligerent drum fills set up the song’s choruses and insistently push the rhythm. Moon was integral to the Who’s musical chemistry. With another drummer, John Entwistle’s virtuoso bass tendencies might easily have gotten out of hand and overpowered Townshend’s chordal guitar playing. But with Moon’s defiant refusal to be a conventional rock and roll timekeeper, the bass had to assume a fair share of the “anchoring” duties. This give-and-take between Moon and Entwistle made for one of the most propulsive rhythm sections ever heard in rock.

The Who were able to assert their unique identity even more strongly on their next two singles, UK hits both: “Anyway Anyhow Anywhere” and “My Generation.” Two of the finest teen rebellion anthems ever written, both are Townshend compositions. “Anyway” features an extended feedback middle section, with Townshend madly flicking the pickup selector toggle switch on his Rickenbacker for extra effect. He was the first guitarist to make musical use of the instrument’s mechanical appendages—its switches and knobs—and of the “accidental noises” generated by electric guitars and amps. He thus pointed the way not only for psychedelic guitarists like Syd Barrett and Jimi Hendrix but also for modern alternative noise guitar bands like Sonic Youth and My Bloody Valentine.

John Entwistle comes to the fore with a thwacking fine bass solo on “My Generation,” but the real fireworks come at the end: another extended feedback raveup that became the basis for the destructive orgy with which the Who now regularly closed their shows. Daltrey’s enraged, stuttering vocal delivery and the venomous line, “I hope I die before I get old” represented an extraordinarily powerful evocation of teenage frustration and anger. By 1965 standards, the song was like a middle finger defiantly raised during Sunday services. Even the Rolling Stones had never made quite so rebellious a statement. “My Generation” became the title track of the Who’s first album, released late in 1965 in Britain and in early 1966 in the U.S., under the somewhat unfortunate title, The Who Sings My Generation. (Their first American label, Decca, was to prove sadly adept at such clownish touches.) The album contains some early Pete Townshend songwriting gems, including the sublime “The Kids Are Alright,” together with vestiges of the Who’s r&b club repertoire.

POP ART AND MINI OPERAS

By 1966, the Who had begun to move away from their Mod image. They began billing themselves as a Pop Art group (more Townshend art school agitprop). Rather than following Mod fashions, they began to design and wear their own clothing based on the bold, simple, geometric and iconic images that artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein were using. This was the era of the Who’s bullseye shirts and Union Jack coats.

Singles were the main rock and roll medium in 1966; “album rock” was still a few years off. And the singles the Who released in ’66-’67 are still the benchmark by which aspiring pop bands measure their work.

Many consider these records to be Townshend’s finest moments (much to Pete’s later undying chagrin). Townshend had been deeply influenced by Bob Dylan, who, in the mid Sixties, freed pop music lyrics from simplistic “baby, I love you” clichés. But while writers like Dylan and John Lennon went after abstract intellectual themes in their lyrics, Townshend stuck resolutely to the notion that pop songs should be about things that kids can relate to. He just put a wry twist on conventional pop themes. In “Substitute,” the guy gets the girl, but only because the girl can’t get the guy that she really wants. So the poor slob in this song goes around in a tortured state because, even if other people are fooled, he knows that, in the girl’s eyes, he’s only an inadequate stand-in. Very Townshend. On another level, the song is about Townshend’s own discomfort with his new status as a pop star and Mod icon, his anxieties over his own “authenticity,” his class consciousness…the whole churning mass of neuroses that are Pete’s artistic stock-in-trade.

Musically, the song is based around another Townshend signature, the I, V, IV chord progression over an open-string tonic (D in this case). This wistful pattern reappears constantly in later Townshend compositions such as “Pure and Easy” and “Cut My Hair.”

“I’m a Boy” is the best song about androgyny ever written (years before the Glam era, too), and it’s also probably the funniest. It’s all about some hapless little shaver whose mother wanted only girls, so she refuses to acknowledge that he’s a boy and makes him wear dresses. But any kid whose parents ever forced him to be something he isn’t can identify with the song. Musically, the tune sounds deceptively simple. The minor-key bridge is actually based on a fairly complex chord structure that ascends gracefully back to the song’s poppy major-key verse and chorus. It’s Pete’s succinct and essential lesson in How to Write a Bridge.

“The chord structure in ‘I’m a Boy’ and the opening chords in ‘Pinball Wizard’ were directly influenced by a piece of music by [I7th century English composer] Henry Purcell,” Pete once noted, “which I’m sure a lot of our fans will flinch at.”

“Pictures of Lily” pioneered another standard Townshendism and all-around heavenly pop move: the chord progression based around a descending major scale. The song also offers a classic early example of the Townshendian key modulation in the chorus (from C to A in this case—one more pop songwriting essential. “Pictures of Lily,” moreover, is probably the best song ever written on the topic of beating off.

In short, Pete Townshend was (and is) a brilliant innovator of the pop song as a storytelling vehicle. Where he was heading with his innovations came into sharper focus on the Who’s second album, A Quick One. The title track, “A Quick One While He’s Away,” is Townshend’s—and the world’s—first rock mini-opera. Running some 10 minutes in length, this slight tale of infidelity and ultimate forgiveness isn’t too far removed from many conventional operatic plots. The “opera” format freed Townshend from the conventional verse-chorus-bridge pop song structure, while still allowing him to build the bright poppy musical themes at which he has always excelled. Lightweight, fun and gimmicky, “A Quick One While He’s Away” was the harbinger of greater things to come.

A Quick One is perhaps the most democratic Who album. There are two songs by Keith Moon, two by Entwistle and one by Daltrey. Entwistle’s contributions—“Boris the Spider” and “Whiskey Man”—established the bassist’s macabre sense of humor and his ability to play a cool rock solo on the French horn. In the United States, the Quick One album was released as Happy Jack, after another one of its tracks. This was the first Who single to make a significant dent on the American charts. The first time this song came on my suburban teenage radio, I had a temperature of 104 and was a bit delirious. I truly thought I was going mad. After I’d recovered, I realized that the drums on “Happy Jack” really do sound like that.

By the time Happy Jack hit, the Who had finally made it over to the States. Lambert and Stamp managed to get the group on one of New York disc jockey Murray the K’s package shows at the Brooklyn Fox theater. (Cream were the other new English band on the bill.) The band covered a lot of American turf in 1967, on tour with Herman’s Hermits and on their own. The Who and the Jimi Hendrix Experience were the two explosive acts that rocked the influential Monterey Pop Festival in June of 1967. It had only been about a year since a then-unknown Hendrix, just arrived in London from America, had walked into Marshall’s music shop and demanded to buy the same kind of Marshall amp that Pete Townshend used. He had to be told that Pete had moved on to Hiwatts by that point.

Also released in 1967 was the band’s third album, The Who Sell Out. One of the all-time great rock albums, the disc includes the Who’s first forays into psychedelia. “Armenia City in the Sky” is a tour de force of trippy backwards guitar work. The album’s big single, “I Can See For Miles,” was pivotal in making the power chord a central part of the rock guitar vocabulary. Townshend’s brash solo—a single E note rapidly double-picked for a space of some 10 bars—was a wry sendup of the growing vogue for drawn-out, self-indulgent guitar solos.

Townshend’s drive to expand the rock song format continued on Sell Out, one of the first concept albums. The songs are linked by glitzy jingles and musical tags from Radio London, the illegal pirate radio station that operated from a boat off the British coast during the mid Sixties. Some songs take the form of commercials written for actual products—Heinz baked beans, Odorono deodorant, etc.—and performed by the Who. Townshend, Moon, Entwistle and Daltrey’s album cover photos were also done as advertisements (Daltrey, who sat in a tub of ice cold Heinz baked beans, later caught pneumonia), complete with hilariously smarmy ad copy.

Sell Out truly upset many among the growing legion of barefoot, sprout-eating, self-righteous hippies, who stood in bovine opposition to anything that was “commercial, man.” With his Pop Art background, Townshend was more inclined to view advertising as a valid 20th century art form. The Who publicly declared their love for commercials, and recorded radio ads for everything from Great Shakes canned milkshakes to the American Cancer Society. And so it went throughout the late Sixties. Townshend’s alliance with the hippy “counterculture”—which was quickly becoming America’s mainstream youth culture—was always an uneasy one, at best.

Sell Out concludes with another fine Townshend mini-opera, “Rael.” Although the plot is obscure—something about the Red Chinese, apparently—the work contains the musical themes that were to become the “Underture” for Tommy. A staple of the Who’s live shows for years, this ethereal-yet-powerful guitar piece again finds Townshend moving high-string chord shapes over tonic bases on the open lower strings.

Who fans had to content themselves with a few singles and some repackaged albums (the Magic Bus album in the US and Direct Hits in the UK) during 1968. But word of something big was starting to spread in Who circles. A growing tide of gossip and speculation hinted that the band was at work on a project far grander than anything that even they had attempted before.

TOMMY

The New York premiere of Tommy in 1969 was a banner event in a year full of auspicious rock happenings. The Fillmore East was a stately, if slightly rundown, old theater in Manhattan’s bohemian East Village. It seemed the ideal venue for the unveiling of the Who’s new opus. Nobody was certain of what to expect. The printed program distributed at all the Fillmore shows had been supplemented with a complete libretto for this performance. A ripple of electric energy surged through the crowd as the Who took the stage and slammed into the majestic opening chords of the overture. They played straight through the hour-plus musical work while the Joshua Light Show flashed incandescent images above the stage—not the usual acid blobs, but images drawn from the story itself, shattered mirrors and flying doves that seemed to swoop out into the charged atmosphere above the audience’s heads. By the time the final chords had subsided, one thing was clear: rock music had been elevated to a new artistic level. But, as if to reassure everyone that it still was rock and roll, the band reappeared after an intermission and tore the place up with a raucous set of old Who hits.

By the next morning, it seemed like everyone had bought a copy of Tommy and was avidly discussing the record. “What did it all mean?” “What actually happens in the end?” As he’d done on a smaller scale in the past, Townshend had once again woven about half-a-dozen of his favorite themes into one piece of musical storytelling. His devotion to the teachings of Indian guru Meher Baba at the time are reflected in the story of the deaf, dumb and blind boy’s spiritual awakening. And poor Tommy was definitely a kid who’d been messed up by his mum; the opera is a kind of dark retelling of “I’m a Boy” in that sense. And in Tommy’s rise to superstardom and subsequent fall from mass adulation, it’s not hard to see Townshend’s perennial discomfort with his own fame and his growing obsession with the relationship between a rock star and his audience.

Tommy demonstrated Townshend’s growing ability to handle a lengthy composition that was compelling from beginning to end and generously laced with songs—“Pinball Wizard,” “I’m Free”—that could stand on their own as hit singles. Other late Sixties groups tried to elevate rock to the level of art by inserting increasingly longer and more intricate instrumental solos in the songs. They tried to turn rock into jazz. Townshend chose to expand the rock song form itself—a far more organic and ingenious approach.

IN THE SEVENTIES

When you’ve taken rock music to a new plateau, what do you do for an encore? The Who chose to go back to basics, releasing a bruisingly tight, no-nonsense concert album. Live at Leeds reflects what a great live band the Who had become in the six or so years they’d been together to that point, and it still stands as the definitive live rock album. Some of the songs go back to the Who’s early days in the clubs of London, but the sound reflects the new, heavier aesthetic that was coming into vogue in rock at the dawn of the Seventies.

Onstage, Townshend had abandoned the Fenders he’d played in the late Sixties (he stopped playing Ricks live about ’67) in favor of the meatier sound of Gibsons—first SGs and later Les Pauls. Live at Leeds underscored the favorable impression the Who had made at the Woodstock festival the previous year. Between their exposure at Woodstock and the tremendous commercial success of Tommy, the band’s place in the States was finally assured; they were showing a profit for the first time in their career.

In keeping with the new vibe of the Seventies and with their own maturity, the Who had long since discarded their Sixties dandyism. Townshend began sporting the scruffy beard of an ascetic, plain white overalls and workman’s boots, like some socialist leader. And indeed, Pete was now striving to put a wildly ambitious piece of populist theory into action. He called the project “Lifehouse.” The idea—or part of it, anyway—was to do a series of concerts at London’s Young Vic Theatre for a small, select audience that would return to the theater night after night. Townshend was hoping to create a closer bond between artist and audience than had ever existed before, where the distance between the two would blur and ultimately disappear.

Pretty trippy, eh? Not surprisingly, it didn’t work; the invited audience just kept yelling for Who oldies. But while the “Lifehouse” project was never completed, it did supply some killer songs for the immensely popular Who’s Next album in 1971 and Townshend’s first solo record, 1972’s Who Came First. “Lifehouse” has continued to obsess Townshend down through the years; themes from the project also crop up in his latest solo album, Psychoderelict.

The year 1971 saw the release of the band’s most popular album, Who’s Next. Roger Daltrey’s hyper-Wagnerian primal scream near the end of “Won’t Get Fooled Again” has become the club call of party dudes everywhere. But in the song’s context, it’s more of a scream of pent-up frustration than euphoria. “Won’t Get Fooled Again” is another classic Townshend statement on the futility of revolutions—in politics, in rock, in youth culture—and the idea that any hero selected for mass adulation will inevitably turn out to be a disappointment.

Who Are You reflects the Who’s new emphasis on a heavier sound, as well as Townshend’s growing fascination with synthesizer technology. Pete later explained that the synth pattern in the FM rock staple “Baba O’Riley” was generated by one of his “Lifehouse” concepts. He had planned to select audience members and feed their biographical data into a synthesizer: “height, weight, astrological details, beliefs and behavior, etc… The synthesizer would then select notes from the pattern of that person. On [‘Baba O’Riley’] I programmed details about the life of Meher Baba and that provides the backing for the number.”

Townshend’s next project was nearly as ambitious as “Lifehouse,” but far more successful. Released late in 1973, Quadrophenia was the Who’s second double-disc concept album. It rocks much harder than Tommy, but as always it’s crammed with Townshend ideas and obsessions. Still striving to enfold real life into his art, he hit on the idea of using the Who’s four violently disparate personalities as a structural device to advance his story of Jimmy, the disenchanted Mod kid. He wrote a musical theme for each band member and the themes are woven throughout the album, embellished with plenty of fluid guitar riffing.

By 1973 rock had become a bloated, boring commodity. It was typical of Townshend that he chose that very moment to recall the pre-hippie innocence of Mod. Quadrophenia is an elegiac record. Songs like “I’ve Had Enough” and “The Punk Meets the Godfather” reflect Pete’s growing weariness with the whole process of stardom. Pete had long since begun to feel trapped by what he’d created with the Who—the obligatory guitar smashings and hotel-room trashings.

The album ushered in a rough period for the Who in the mid to late Seventies. Keith Moon’s substance abuse had ceased to be charming or amusing (if it ever was that) and had begun to damage the drummer’s health; he collapsed on stage at several shows. Townshend’s own problems with alcohol were beginning to become chronic, turning him into a bitter, self-deprecating and generally unpleasant figure. (Onstage at a mid Seventies orchestral performance of Tommy in London, he made a self-loathing mime of wiping his ass with the libretto.) Meanwhile, the Who were having trouble presenting Pete’s newer synth-scored, complex narrative songs on stage. Backing tapes and awkward spoken explanations of Quadrophenia’s storyline had begun to hobble the Who’s awesome live power. All four members of the Who had begun putting a good deal of their energy into solo albums; Daltrey and Moon had budding film careers as well.

All of this turmoil is reflected in 1975’s The Who By Numbers. There are a few good songs, but the overall feeling of the record is brittle and strained. It was the first disappointing Who album ever. Townshend’s “However Much I Booze” pretty much tells the whole story. Luckily, the Who were able to rally their creative energies for Who Are You in 1978. Some of the songs (“Guitar and Pen,” “Music Must Change”) are a bit “show tune,” reflecting Townshend’s growing love affair with the musical theater. But most of the songs, including the title track and Entwistle’s bruising “Trick of the Light,” are among the hardest rocking songs the Who ever recorded.

THE MUSIC MUST CHANGE

Who Are You turned out to be the Who’s swan song. A month after the record’s release, Keith Moon was found dead in his London flat, killed by an accidental overdose of the pills that had been prescribed to help him control his drinking. Rock had lost its foremost jester, its chief Dionysian celebrant. The Who, meanwhile, had lost their drummer. They chose to carry on for two more albums (Face Dances and It’s Hard) with former (Small) Faces drummer Kenny Jones and keyboardist John “Rabbit” Bundrick. The last two albums contain some fine tunes, but it’s difficult to call them “Who albums” in the same sense that the term had been used since 1965. Townshend half-acknowledged as much in a 1989 Musician interview with Charles M. Young, saying that the Who was no longer “the name of a familiar group of musicians, because once Keith died that was dead. It’s become a kind of ideology—a sense of personal emancipation as opposed to political or economic emancipation. We who are in the Who should know that it’s impossible to invoke that other kind of music without Keith. So I felt the band without Keith was a new band.”

When that new band decided to call it quits in l982, the Who became a memory—a legend. In 1989, Mssrs. Entwistle, Daltrey and Townshend got together with a group of ace musicians to celebrate that legend in a series of moving concerts commemorating the Who’s 25th anniversary. Then they went back to their everyday lives: A bass virtuoso who’s a regular figure at NAMM shows. A capable actor and one of the finest rock singers/song stylists still practicing the craft. And a successful writer, literary editor and composer for the musical stage, who currently has a hit called Tommy on Broadway and another called The Iron Man in London’s West End.

In 1993, I attended Townshend’s Psychoderelict concert in Los Angeles—a typically ambitious presentation that was part rock performance and part legitimate theater, which brought actors and musicians together on the same stage. In the lobby, I was amazed and delighted to discover that Who crazies still exist. There was that same vibe: complete strangers approaching one another, saying, “Hey, did you hear that Entwistle’s here tonight? Did you know Pete’s gonna release a version of the record without the spoken bits?”

During the performance, I experienced a sensation I hadn’t felt in at least 15 years. Having attended literally thousands of rock shows and seen bands go through their predictable paces, building to one tediously inevitable climax after another, I suddenly realized that, at this show, I actually didn’t know what the hell was going to happen next! There was that same anticipation and uncertainty that one felt at Who shows long ago: the sense that the whole thing could at any moment disintegrate into total garbage—or be absolutely brilliant. And there was Pete Townshend up on the stage, his hair gray and thinning, but still pushing the envelope, taking chances, trying to stretch the limits of what can be done with rock and roll. Thank you for that, Pete.