Tony Levin: "Improvisation that has to fill in all the spaces with notes is pretty dreadful to listen to"

The Peter Gabriel and King Crimson bassist on his favorite bass albums and what makes him pick up the Chapman Stick

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

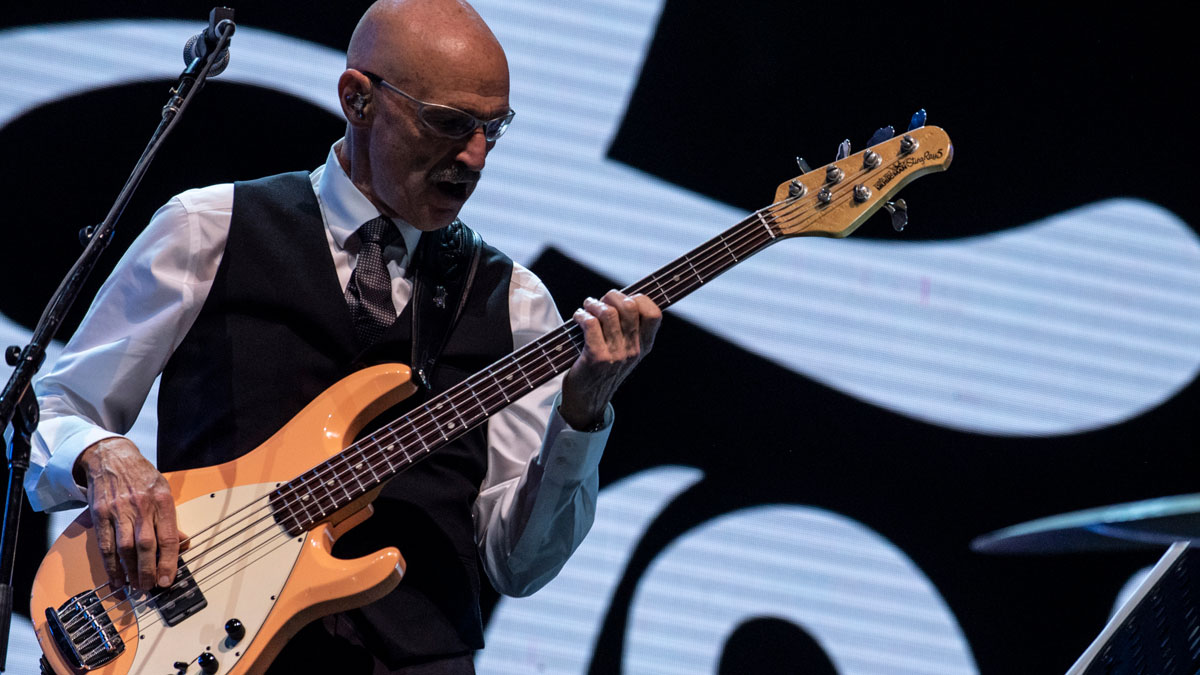

Tony Levin is a man whose credentials speak for themselves. He has spent many years supplying basslines of impeccable quality in Peter Gabriel’s band as well as holding down tours with perhaps the most innovative of all the old-school prog acts, King Crimson.

He has played sessions with artists as diverse as Pink Floyd, Lou Reed, John Lennon, Tom Waits and Dire Straits, and he’s been a founder member of groups such as Liquid Tension Experiment, Bruford Levin Upper Extremities and his own Tony Levin Band.

Another venture is the excellent Levin Torn White, in partnership with drummer Alan White of Yes and guitarist extraordinaire David Torn. In between all this bass magnificence he plays the Chapman Stick, the most intimidating musical instrument ever devised, in a variety of ensembles including the self-explanatory Stick Men.

As a master of both the bass guitar and the Stick, does Levin feel that his playing on either instrument benefits the other?

“I don’t really think about the crossover between the two instruments,” muses the great man.

“I mostly play bass parts on the Chapman Stick, of course, and they’re pretty different than what I can play on bass. The tuning being different effects the parts that lay easy, and it’s a pretty fast instrument, with only tapping to produce the note.

“What makes me choose one particular instrument over another is usually the music being played: some songs seem just right for the Stick, and others for the bass. Of course in Stick Men, I’m doing a lot of the writing on the Stick, and the top side [ie the top strings of the instrument] is a necessity.”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

One of Levin’s famous innovations is the remarkable Funk Fingers, small wooden drumstick-like extensions which he attaches to his fingers for a staccato tapping effect.

“They’re really percussive, as you’d imagine,” Levin chuckles. “They’re pretty easy to use when the part is on one string, but not so much with string changes! I’ve used them a lot with Peter Gabriel, and back when I played with a version of Yes. They make a nice sound that’s different than just hitting the string.

“I have to compress it some, and certainly turn down the highs – how much depends on which set I’m using. Some of them I have wrapped with soft tape to keep the thud but without the ping of the attack.”

We discuss Peter Gabriel, a famously unorthodox musician…

“Sometimes Peter gives me ideas, or even a complete part on his keyboard: sometimes not. Sometimes I love his suggestion and play it as is, but sometimes I feel I need to make it more, let’s say ‘bass player-like’ to satisfy me. Then we’ll negotiate.

“A funny example is the song Big Time, where on the recording I had Jerry Marotta drum on the bass strings – in fact, that later led to the Funk Fingers being developed – but for most of the song, my part was replaced with a synth bass part that was nice: sparse, kind of funky and very quirky.

“I found that live I just wasn’t feeling good playing that part, so I reverted more and more of the song to be like the funk finger intro. Then when Peter once in a while heard a tape, he’d remind me of the other part. ‘Oh yeah... oops, I forgot...’”

As well as these high-profile shows, Levin used to play from time to time in a jam band called HoBoLeMa, whose name is derived from those of the participants (our chap plus guitarist Allan Holdsworth and drummers Terry Bozzio and Pat Mastelotto).

The unique selling point, as it were, of this group is that their sets were entirely improvised. Not partly; entirely. So how do the jams begin and how does the bass drive them, we ask?

“It’s such good fun with that ensemble and in that format,” he says. “It’s total improv: not jamming or finding grooves and staying on them, but constantly looking for textures and new ideas, and most importantly, listening to the other players.

“The reason it worked so well for me is that these players are really excellent and had trust in each other, so nobody felt they needed to fill in all the spaces. That means there can be more space, and, to me, improvisation that has to fill in all the spaces with notes is pretty dreadful to listen to!” He has a point, we reckon.

Levin adds: “Our sets were all the same, even though they were all different. We’d ask how long we were to play, and it would often be a 40 or 45 minute set, so we – one or more of us – would start to play, and 40 or 45 minutes later, we’d stop. There were no clocks involved, it just seemed to organically work out that way every time.”

He continues: “As for the bass function in HoBoLeMa, I had a lot of sounds available – the Chapman Stick, and the NS Electric Upright. I take along a bow to use on either, and there are plenty of pedals in the chain, so I could play a punchy rock part, or a jazz feel, or long notes, or backwards notes, or chords on the top of the Stick, or build up spacey harmonics.

“To me, having a lot of options helped in the challenge of trying to play different each set and each night. A huge help, of course, is that I could always lay low – pun intended – and let someone else lead us in a new direction, then follow along. I didn’t need to be the musical traffic director each night.”

Asked to recommend albums with killer bass playing, Levin gets listing…

“Oscar Pettiford’s Tricotism is an album I grew up with. I’m not really sure the name is right – it’s really a series of albums with the same players, Julius Watkins on French horn, and Charlie Rouse on sax. It has great, tasty playing, especially by Pettiford – he always hits the right notes, and they’re always placed perfectly for maximum groove.

“D’Angelo’s Voodoo made me want to go back to school, figuratively, as a bassist. It was a a new kind of groove (to me) that broke all the rules I grew up with, but was amazingly cool. I raved to my fellow players about it, and tried to introduce that kind of playing to some of my music – I couldn’t do it... so it’s still on my list of ‘got to learn this, dude.’

“Then there’s Sleepytime Gorilla Museum’s In Glorious Times. I love this style of music – it has great power, great musicianship and great bass playing by Dan Rathbun, sometimes on instruments he built himself. One thing you gotta love about music: this band may have been influenced a bit by King Crimson, but then I, a member of Crimson, was very much influenced by them!

“With Stick Men, I insisted we do a piece of theirs for our first year on the road, though it was tough and not a great rendition, just to get us thinking in that vein. Finally, there’s Joni Mitchell’s Hejira. Jaco’s playing before that had impressed me, but it didn’t move me, maybe because it was so far from the styles I played.

“But the bass playing on this album is sublime: to me it’s the apotheosis of fretless playing behind a singer. It is beautifully melodic on its own, but never interfering with the great vocals, unique harmonically, with a style of its own, and impeccably in tune... I put the fretless bass away for 10 years!”

The gear which Levin uses to deliver the low notes:

“With Stick Men, I’m playing the Chapman Stick. The bass side goes to an Ampeg 800-watt top and a tilted wedge-style speaker. The top side of the Stick, which is essentially a guitar amp, goes to a mini stack, a BlackHeart 15-watt guitar amp with two cabs.

“On both sides I need an Ernie Ball volume pedal. The bass side gets compressed with an Analog Man Compressor, then the fuzz tone is one of a few I have with me – a Pigtronix Disnortion or Radial Bones. I have an Electro-Harmonix Memory Man for echoes and backwards. My tuner is a DigiTech.

“The top side goes through a Pigtronix Disnortion and Philosopher’s Tone, a DigiTech delay/looper, and a Peterson tuner. In the Crimson part of the show I’m playing my usual bass, an Ernie Ball Music Man Stingray 5. It goes through the same effect chain, but I don’t use many effects on it.”

Bass Player is the world’s most comprehensive, trusted and insightful bass publication for passionate bassists and active musicians of all ages. Whatever your ability, BP has the interviews, reviews and lessons that will make you a better bass player. We go behind the scenes with bass manufacturers, ask a stellar crew of bass players for their advice, and bring you insights into pretty much every style of bass playing that exists, from reggae to jazz to metal and beyond. The gear we review ranges from the affordable to the upmarket and we maximise the opportunity to evolve our playing with the best teachers on the planet.