Veteran record producer Don Was names his 5 all-time favorite bassists

Producer Don Was on his favorite players, how to get a great bass tone, and the most common mistakes people make in the studio

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Meet record producer Don Was. In the studio, he’s the man in charge of bringing together the different elements of a recording project, from delivering the finished mix to the record company right back to the initial hiring of session players. How does he decide who to call?

“I love Hutch Hutchinson on bass guitar,” he told BP back in 1994. “I probably use him more than anyone else. Then there's Lee Sklar, who's a wonderful bassist, and I like to use John Patitucci for the acoustic stuff. I love to shake it up, though. There's a guy in Nashville named Glenn Worf who plays an upright through an Ampeg B-18, and it's an ungodly sound! But my favorite bass player was Willie Dixon, who had a simple style. It was really basic, strongly supportive, and incredibly rhythmic, but he was also as distinctive as Jaco.”

Having produced everyone from John Mayer and Elton John to Guns N' Roses and Bob Dylan, Was is often lauded as the definitive musical journeyman, but let's not forget that he's also garnered a measure of fame as a bassist himself. In the late '80s, his band Was (Not Was) had a Top Ten hit with Walk the Dinosaur. He also backed an all-star cast that included Bruce Springsteen, B.B. King, and Bonnie Raitt for a tribute to Curtis Mayfield at the 36th Grammy Awards.

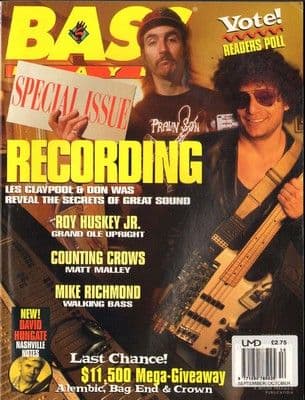

The following interview is from the September 1994 issue of Bass Player, which followed the release of the Rolling Stones Voodoo Lounge album, which Was produced. He also played acoustic bass guitar on two B-sides, Get on Top of Me and I'm Going to Drive.

What do you look for in a bassist?

"I look for the same things I look for from everybody – I want them to help the band become a breathing entity unto itself. Everyone is supposed to be part of a solid foundation, even the melodic instruments, because everything's a brick in the wall. I don't focus on just one instrument; I focus on the whole – it's about learning to see the forest from the trees."

How would you describe a good bass tone?

"It varies from song to song. On the sessions I've been playing on lately, I've been going for an indistinct blur – it's the total opposite of everything I had wanted previously. I spent years trying to get the round crispness James Jamerson had, and this 'thud' sound is 180 degrees from that. You almost can't recognize what notes you're playing."

How do you keep those blurry notes from getting lost in the mix?

"I've found if you leave some room around 700Hz and 1.2kHz, the bass speaks more clearly. It's not a matter of turning up the volume, but of EQing it right, so the note is articulated. If you just turn it up, you get a lot of boom – maybe you'll hear the bass more, but it's going to blow up the speakers in people's car doors."

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

When you record your own bass playing, what's your favorite rig?

"I usually go with my Sadowsky plugged in direct and an Ampeg B-15M amp; I was turned on to the Sadowsky by Hutch, who owns a 5-string. Darryl Jones also used a Sadowsky with the Stones. While I was working with the Stones in Dublin, I played bass on a tune for Marianne Faithfull – Darryl had left, so I picked up his Sadowsky and recorded the track. When I heard the playback, I thought, 'Man, that's not me – I've never sounded that good!' So I bought one, and it's the coolest bass I've ever played."

How much does the mastering process affect a bass tone?

"Tremendously – you can do amazing things when you master records, but sometimes what happens after a record is mastered has an even greater effect on the end result. When I helped the Stones reissue their catalog, Bob Ludwig spent an incredible amount of time on the remastering. Then we discovered that somewhere in the CD-manufacturing process there's something called 'jitter' that can dramatically change the quality of a disc. So even after the remastering, on the discs we got back all the warmth of the bass had vanished."

What should a good producer do for an artist?

"Basically, a producer should bring out the best in an artist. I believe a good artist is someone who has a vision and a point of view; a good artist also has the communication skills to express themself in an eloquent fashion, so that 100 years from now when you hear their performance, you're going to feel the emotional content as freshly as when they wrote the song. I think it's the producer's job to realize this concept to its fullest."

How much involvement in a record should a producer have?

"There are some producers, like Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, who are the artist – they're the type who write the songs, play all the instruments, and tell the singers how they should phrase. Then there's the opposite type, who's on the phone ordering food or reading magazines. Both types have been responsible for some incredible records."

Which type are you?

"I fall right in the middle. I don't believe I'm the artist – I'm attracted to those who don't need a vision shaped for them. But because I'm a musician, I love being involved in the details of arranging a song. I like to sit in the room with the musicians and wear headphones as they record. If I'm not actually playing, I'm acting as a member – I believe in actively participating in my work."

Do you suggest things if an artist needs direction?

"Sure. I believe if an artist is putting in the work and is as emotionally involved in the record as they ought to be, somewhere in the middle they'll lose all perspective – it happens to everybody. The artist then needs someone who's less emotionally involved, someone who has a sense of where it is the artist is trying to go and can offer some concrete ideas about how to go about getting there – but in a way they would do it. If I suggest phrasing to a singer, for example, it should come out sounding as if they would have phrased it that way."

How do you inspire creativity in someone who's reached burnout point?

"Creativity is an organic thing – it's a vibe that's set long before you record the first note. An artist knows when a producer wants him to hack out something. I don't have a list of things I do, like dim the lights or serve champagne – people either feel comfortable about stretching or they don't. I, myself, got involved in playing music because I didn't want to go to work. I'm doing this for myself, and I'm trying to create a fun atmosphere to work in."

Is there a Don Was sound?

"Hopefully, there's a trademark of invisibility! My goal isn't to leave my personal stamp on things. If I were a photographer taking a picture of Willie Nelson, I'd want to create a photograph that gave you some sense of who he is. So when I produce people's records, I try to take honest black & white pictures of who they are and what's on their minds at this particular point in time."

What are the most common mistakes people make in the studio?

"Even the most established artists make big mistakes, the most common being a lack of good material. You can't sing or play a shitty song well enough to make it good! It's like shooting a movie with a bad script – you could get Al Pacino and Laurence Olivier to play the parts, but in the end it's still going to be a shitty movie. I deal with that all the time, and I have no qualms about telling people the songs they've written aren't good enough for them."

Doesn't that lead to some conflicts?

"Well, I don't say it in those words! I might say, 'Look, you're the person who wrote such-and-such a classic tune, and this song isn't worthy of your legacy. If you can't at least make an effort to write at that level, then why are you bothering to make a record?'"

Have there been times when you wanted to re-track a performance, but the artist refused?

"Here's my philosophy: Never produce an artist you mind losing an argument to! Certainly I'm not always right – sometimes I'll see what they were going for after we talk about it. If you're going to work with someone, you should have respect for them as an artist. If they feel strongly about something, then maybe they're aware of something you're not."

Do you ever get pressured by record companies to produce hits?

"That's always implied, but I try not to think about it. Whenever I've done something specifically in the name of making money, it never did. So I try to forget about record company pressures and just try to make the best record I can. When you cut a song that's got some magic on it, you can usually tell if it's a single or not. Then again, I don't think I would have picked Love Shack by the B-52's as a single, but it ended up being the biggest song I ever had! And I begged Chrysalis not to release Walk the Dinosaur."

It was a hit!

"Sure, but it ruined the band. I was actually right that time! But seriously, there are people who make some cynical records in the name of money – the Milli Vanilli album Girl You Know It's True is probably the standard by which we measure cynicism. There were some calculating motherfuckers at the core of that record. Personally, I thought it was incredibly well crafted – it didn't matter to me whether those guys sang on it or not. Who cares if Audrey Hepburn actually sang in My Fair Lady? It's all entertainment. The bottom line is that you don't sell records unless you connect with people."

How do you feel about the "fix it in the mix" approach?

"It's not that you fix it, but that you sculpt it. Maybe there's a good song in there you haven't quite found yet. There's a tune called I Go Wild on the Stones album that turned out great, but it took some experimenting to get it right. We had set up Charlie Watts's drums in this three-story stairwell and miked them from the top – the sound was huge. The problem was, the sound ate up so much space there wasn't room for anything else! So until we spent some time cleaning up that ambiance and taking out the ugly aspects of the room at mixdown. We knew there was something good lurking in there, but we had to work to find it."

Do you like to track live?

"I prefer it, but I can understand how in certain situations someone might be able to play a part better at another time – I don't rule anything out. If someone's going to lay down ten tracks of guitar, which I don't encourage, I'll go through those tracks and pick the best performances right afterwards. The closer you are to the moment, the clearer your perception about whether you achieved what you were going for. To go back and redo a vocal or bass part three weeks after the fact doesn't seem to be a very effective way of working."

It sounds as if being open to different approaches is an important factor in getting a good-sounding record.

"Right. The key is not to fall into a pattern and create a formula, because I think that can make for a stale sound. You almost have to seek out change and make it a point not to repeat yourself. On the other hand, not having a formula then becomes your formula. I believe songs have a DNA code – if you read the code right, you'll know how the song is supposed to come out."

In what direction do you see music headed?

"There's a generation of people who have grown up watching music – and as they become artists, hopefully they'll find the key to combining these media into a more organic form. If you make a record properly, you've left the right amount to the imagination; the holes you've left should be there intentionally. In a way, a video is an extension of this perfectly formed piece of art. The generation of artists who are going to nail this are probably in film school right now."

So what will the band of the future be like?

"It won't have two guitar players, a bass player, and a drummer – it will have one guy who can make music, one guy who can run a Hi-8 video camera, and one guy who can edit stuff together. I think people my age are probably too set in their ways to really conceive of this as a pure art form."

As a producer, how will you keep up with the changes?

"When I started, I was inspired by people like Jerry Wexler and Arif Mardin, who began with Ruth Brown, went through Led Zeppelin, and ended up with Scritti Politti. They managed to keep their vocabularies current and evolved. I plan to stay involved in making music-driven art, but I've got to expand my vocabulary – maybe learning about filmmaking will make that happen for me. I'm lucky – I live in the land of all-play-and-no-work, and I'll stay here as long as I don't turn into a donkey!"

Don is currently playing bass with Bob Weir & Wolf Bros, alongside former Grateful Dead guitarist and singer Bob Weir. For more info visit bobweir.net

Karl Coryat was Deputy Editor of Bass Player magazine in the 1990s. In the 2000s, he wrote two music books: Guerrilla Home Recording and The Frustrated Songwriter’s Handbook, the latter with Nicholas Dobson. In 1996, he was a two-day champion on the television game show Jeopardy!. He works as a comedian and musician under the pseudonyms Edward (or Eddie) Current.

- Nick WellsWriter, Bass Player