William DuVall: "That conception of basic musical competence as punk… I wasn’t one of those people. I was on a quest for the truth and jamming to everything"

The Alice in Chains vocalist looks back on his early guitar years as he revisits cult hardcore outfit Neon Christ for a deluxe reissue of their 1984 recordings

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Though he’s arguably best known for co-fronting Alice In Chains alongside Jerry Cantrell from 2006 onwards, recording three studio albums thus far with the Seattle alt-rock heroes, William DuVall has been an incredibly active musician for the vast majority of his life.

More recently, he’s collaborated with Mastodon’s Brent Hinds and The Dillinger Escape Plan’s Ben Weinman in Giraffe Tongue Orchestra and also finished the material for his solo debut, which was released in 2019.

Stretching back further, however, he also played in Atlanta hardcore scene founders Neon Christ, Californian punk rockers BL'AST!, whose 2015 line-up included Dave Grohl, as well as bands like No Walls, Madfly and Comes With The Fall.

This year he’s revisiting his roots in one of those early groups, Neon Christ, having recently announced what will be their first show in 13 years and a Record Store Day reissue of their 1984 recordings, including the original self-titled 7” EP and four tracks recorded during their Labor Day session with Foghat’s Nick Jameson that same year. The tapes were remastered using an all-analog process at Nashville studio Welcome To 1979...

“It’s one of the things I’m most proud of with this release,” DuVall tells Guitar World. “Using an all-analog signal chain to cut vinyl is becoming harder and harder to do these days. I felt that doing it any other way wouldn’t have been as true to where we came from. I think it sounds all the better for it, too. I hadn’t listened to the music in a studio atmosphere since back when it was originally recorded...”

37 years is, indeed, a lifetime ago. Chances are, if you were acquainted with DuVall back then, you probably would have known him as ‘Kip’. It was a childhood nickname given to him by his grandfather, he goes on to explain, and one closely associated with his years playing frenetic punk-rock...

“I put an end to that name as soon as possible,” he grins. “I think I was 19 when I decided I’d had enough. Though I never personally liked it, out of love and respect for my grandfather, and the fact it caught on within my family, I just sorta put up with it. And, to this day, my mother still calls me Kip at home, as will my sisters. But no one else beyond that, not even the guys in Neon Christ. Thankfully, most people know me as William [laughs].”

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You were in your mid-teens when you formed Neon Christ and helped start a new music scene in Atlanta. What was life like back then?

“Honestly, I couldn’t have imagined a better way to come of age! Hardcore was a new kind of music – it was a new iteration of rock and roll. To be on the cutting edge of that, at that age, and have the sound of it reflect so closely what was going on inside of me was a dream come true.

Even though there wasn’t easy access to music back then, you could see a shot of the Pistols and you’d be able to kinda tell what they sounded like

“But at the time, it felt like what was necessary of my survival. I wasn’t sat there thinking I was living the dream, I was just really into music. I started playing guitar at eight years old and came up on what I still feel is the best of the best – working my way up from Hendrix.

“By the time I was 11 or 12, I was discovering '70s punk-rock like the Sex Pistols and the New York scene with the Ramones and Richard Hell. Even though there wasn’t easy access to music back then, you could see a shot of the Pistols and you’d be able to kinda tell what they sounded like.

“When I started hearing their music, they were actually on the news. When they toured the US in ‘78, they had all this controversy and the coverage was extremely negative. That’s what I knew of punk-rock… it was intriguing. But what really got me was this new American form of it called hardcore...”

Which, all things considered, must have felt wildly thrilling to teenage punks at the time...

“The name wasn’t as widely circulated back then, but you’d hear about this music that was faster, harder and more extreme, and of course I was instantly into that! I liked what I heard of the '70s punk stuff but wanted more.

“In my mind, though I loved my MC5 and Stooges, I could imagine and hear things that were more intense, taking it further. And then I heard about Black Flag.

“In those days you’d get little tidbits of information, you might hear the name or maybe see a picture. It was hard to come by anything. I was living in Washington DC, where I’m originally from, and heard a song on a really obscure college radio station from their Damaged album.

“I was like, ‘Okay, this is sounding more like why I’m here!’ Then I heard about this movie called The Decline of Western Civilization which was playing at a movie theater. I persuaded my grandfather to take me and the very first band you see is Black Flag...”

It’s easy to forget with hindsight, but their assault must have felt pretty damn dangerous in its day...

“The second they started White Minority and I saw Greg Ginns slashing up that Dan Armstrong guitar with his bright yellow shirt on, plus the way the band were behaving on stage, I knew this was it. That moment felt like an epiphany. Just like hearing Hendrix a few years before but the difference was these guys were alive now… Hendrix was already gone by the time I discovered him.

“I love how aggressive Ginns’ playing was, but it had these qualities of free jazz about it, which is another kind of music I was getting into, watching groups like The Art Ensemble Of Chicago and listening to Ornette Coleman, James Blood Ulmer and Albert Ayler, plus John Coltrane’s later stuff.

“Ginn seemed to be echoing some of that, the whole adventurous of it. And I could tell it was deliberate. He wasn’t just making noise – it was what he meant to do. Seeing that movie was life-changing, so I decided to form a band like that making my own version of it.”

What was it like then moving from DC to Atlanta?

“It was incredibly frustrating because I was discovering these bands from the DC area, Ian MacKaye and the whole Discord scene – including Henry Rollins, who was just about to join Black Flag. I had to leave all my friends and everything I knew to move to this place I knew so little about.

“And the little I did know was disturbing. Atlanta was the site of the Atlanta Child Murders… I think by then they’d caught the guy they thought was the perpetrator, but even to this day, there’s a lot of mystery around that case and it was very dark.

“I also knew Atlanta from what I’d seen in the Civil Rights films, grainy black and white footage of people being abused. I was like, ‘We’re moving there?!’ I figured the only way I could survive was to form a band like the one I resolved to form in Washington. I didn’t care how it happened – it was a pure survival drive. I was even thinking about running away or moving back to DC where my grandparents were.”

But you chose to stay and form Awareness Void of Chaos, and soon after Neon Christ?

“Yeah, we moved in the summer of ‘82 and that fall I started 10th grade at the local suburb school. It was a mostly black school, one where the academics weren’t so emphasized but, boy, the football team was killing it. Therefore the jocks ran the school.

“They got away with murder and that was it. I walked in as this scrawny misfit kid who was immediately a target – it was written all over me. So in order to survive I had to build the world I wanted to live in.

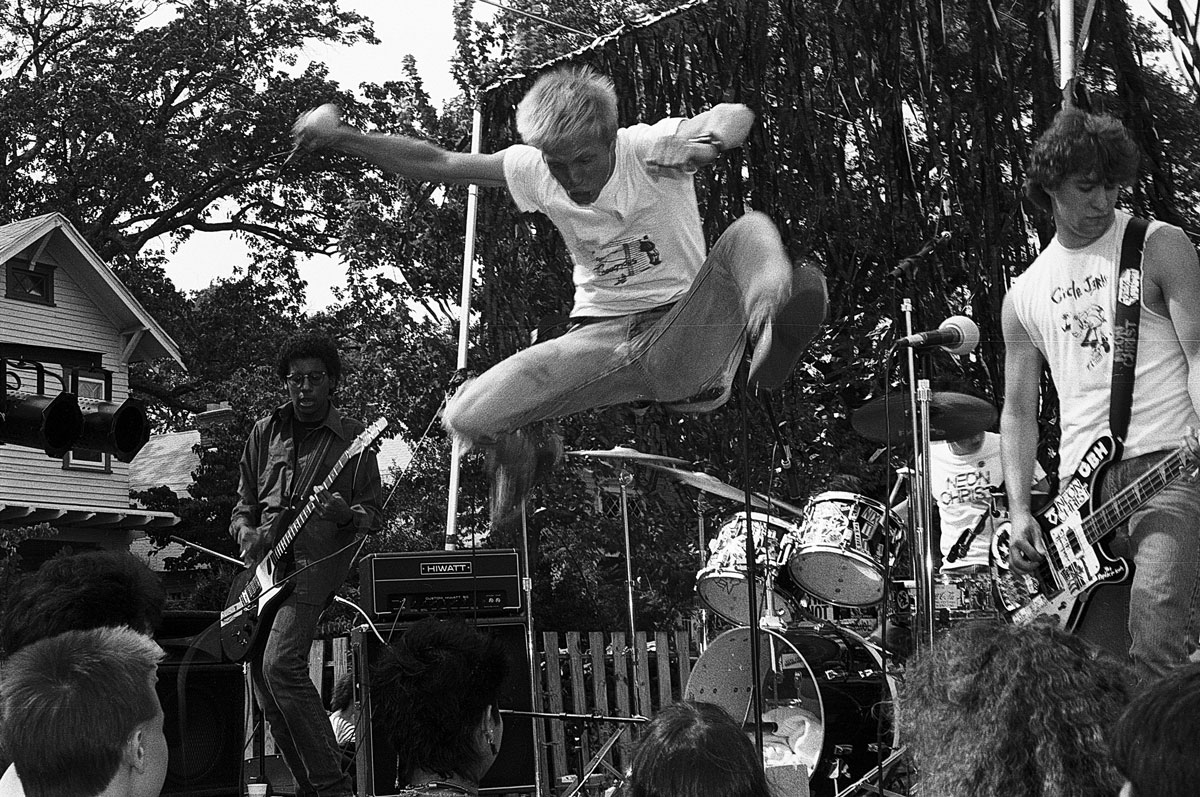

“AVOC was my first foray into creating that. We recorded a one-mic-into-a-boombox demo and I took that tape to the manager of 688 one day, which was the only club that catered to counter-culture. I remember getting the bus downtown by myself. And, to his credit, he gave us – three black kids – a gig.

“That happened, it was cool and everybody survived. So he gave us another gig, opening for The Circle Jerks who were idols of ours and a legendary band from LA. That led to the formation of Neon Christ, because I wanted get even more extreme. AVOC was really cool for what it was. I never would have survived moving to Atlanta without it.

“Once I started meeting more people and crystallizing my vision, I wanted to work with people who practiced every day and were as obsessed as I was about playing faster and more extreme.”

Can you remember what gear you would have used for those early Neon Christ recordings?

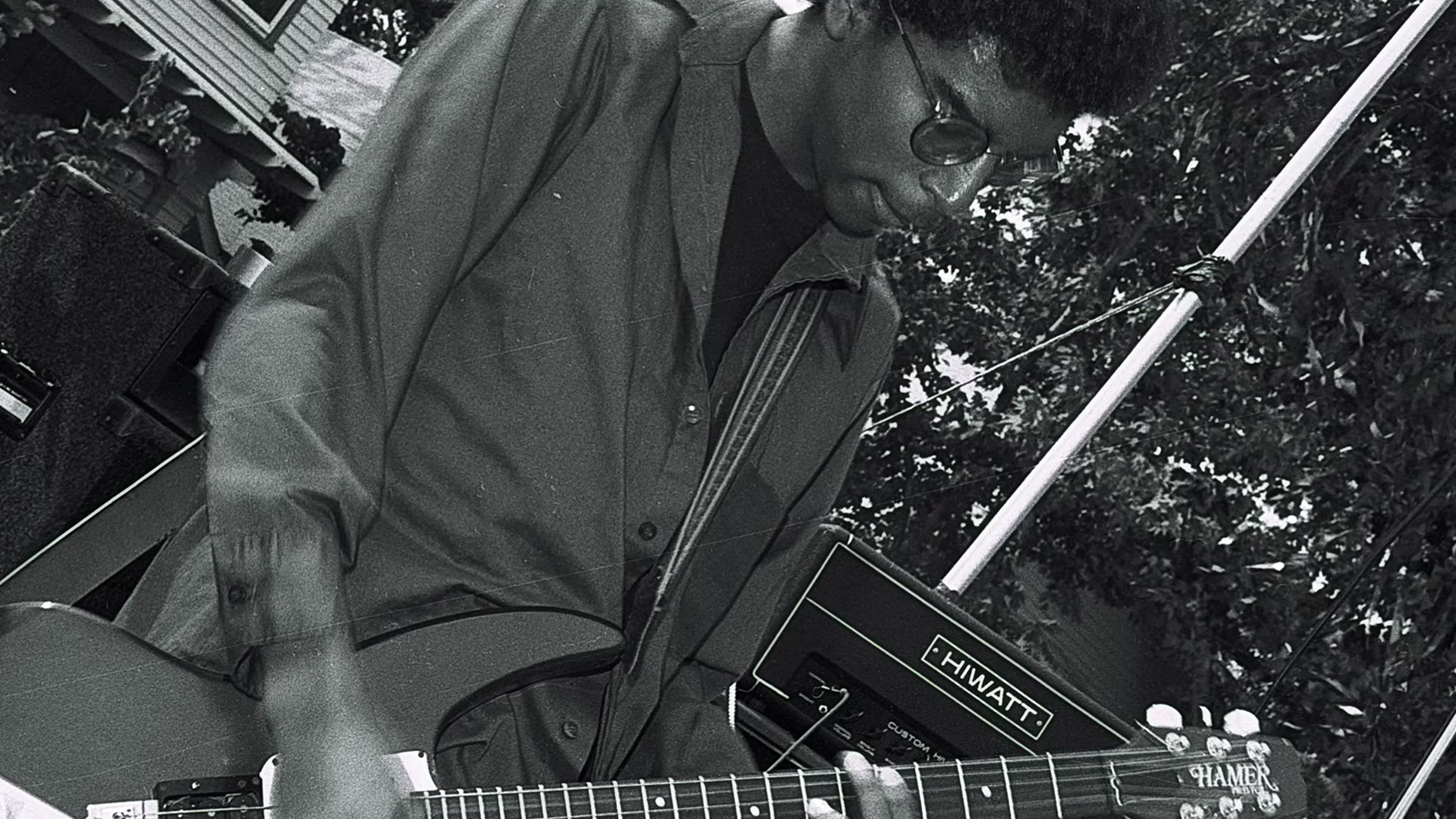

“I had a Hamer Phantom guitar with the triple humbucker. It looked like a Stratocaster that had been melted, with a really elongated upper wing and this slightly distorted double cutaway Strat-esque shape to it. They had the triple humbucker trademarked, with TM at the end, and it also had a single coil in the neck position. I was like, ‘Man, three humbuckers, that mean it’s even louder!’

“Then I got an old '60s non-master-volume Marshall head. You could get those for pennies back then… you couldn’t give them away! I just used to crank it through a 4x12 cabinet. I didn’t have pedals. I didn’t have a tuner. I was lucky to have a cable! I’d just tune to myself and let it rip.

“That’s what I took into the studio for that first EP. We’d never been in a studio before, we didn’t know how anything worked. We just set up like it was band practice and ran through everything we knew.”

It’s interesting how ahead of their time they feel – moments of We Mean Business could have been on a lost Nirvana track and other songs sound like proto-grindcore...

“Well, thank you. It was just about survival for me. I had to create the sound I was hearing in my heart and mind. And you have to remember this kind of music was absolutely hated back then. Even in big towns like LA, the punk-rockers and hardcore kids caught a lot of hell.

“Black Flag were always dealing with skirmishes with the police and their gigs were always getting broken up. They were always getting run out of whatever office space they were trying to occupy for their record label SST.

I didn’t learn how to play through punk-rock, though I learned how to be in a band through punk-rock

“It was always a hassle for them – and they were a major band from a major city, so you can imagine how it was for us, a bunch of kids in this comparatively backwater scene in a backwater town. We were either hated or ignored or completely disdained for what felt like a long time. I was writing these songs for an audience that didn’t exist.

“You mentioned We Mean Business – that song was written in the AVOC days so late ‘82, before I’d even played my first gig. I was trying to write songs for the audience I wanted to see. I was also trying to address all the people who looked down on this kind of music.”

It’s quite defiant in that regard...

“That’s what the lyrics are about. It even has a line that I think is pretty funny now – ‘You try to give me the shaft, use your cunning to kill my craft!’ But that’s how it felt. People who were judging this music didn’t know how cool it was and actually it wasn’t easy to play at all – there was a lot that went into it.

“I think the variety of sounds in the early Neon Christ music was down to the fact I was already a musician when it formed. I didn’t learn how to play through punk-rock, though I learned how to be in a band through punk-rock, plus a tremendous amount of extremely valuable life lessons that have stuck with me to this day.

“But that conception of basic musical competence as punk… I wasn’t one of those people. I was already jamming along to my Hendrix, Nile Rodgers, Velvet Underground and even John Coltrane records, which didn’t even have guitar.

“Anything I could imagine hearing a guitar in, I’d play along to. That’s how I learned to play. It didn’t matter if it was AC/DC or Albert Ayler. I was on a quest for the truth and jamming to everything.”

After, on the other hand, felt more like a pre-Kyuss or Monster Magnet stoner kind of thing...

“Yeah, that atmospheric guitar with some spoken word over the top. It kinda came out of the dark beatnik thing – Warhol, The Velvet Underground and things that. I loved that stuff, but I also loved thrash, which was a new form of music back then, and faster speed rock.

“There’s a song on there called It’s Mine, and that came from old rock and roll like Chuck Berry or Johnny Thunders. As a writer, I was just updating my influences, which is what we all do, or at least hope to do. I just wanted to represent my influences and put my own spin on it.”

And from there you went on to play in a number of bands – BL'AST!, Final Offering, No Walls, Madfly, then Comes With The Fall and, eventually, Jerry Cantrell’s solo band. That’s a lot of sonic ground right there...

“Some people might have felt that was a handicap for me when I was younger. Because it may have seemed like I couldn’t decide what I wanted to do [laughs].

“Some people find their scene and ride it as far as it will take them and I couldn’t do that… and there were times where I wished I could! I felt like musicians who were more streamlined and focused in their desires had a straighter path.

There wasn’t ever anything that held my interest long enough for me to say, ‘I just do this!’

“With me, it was more challenging. There wasn’t ever anything that held my interest long enough for me to say, ‘I just do this!’ By the time I was in BL'AST!, I was already really burning out on the punk and hardcore-inspired rock music.

“When you’re younger, things move faster, especially in terms of your attention span. AVOC, Neon Christ and BL'AST! took me from 15 years old to 20. Those years are monumental in your development, whatever you’re doing.”

Congrats on the MoPOP Founders Award with Alice In Chains, by the way. What were your favorite performances on the night?

“That’s hard, because like you said, they were all so good and it was really moving to see. Fishbone was very special, that one really warmed my heart. I love what they did with Them Bones because they really did it their way, with horns and everything.

“I really loved [City And Colour] Dallas Green’s Rain When I Die. It was one of the very few we saw before the show aired because we made a concerted effort to not supervise and micro-manage this event. We looked after our segment, but the rest we left to the director and artists.

“We wanted to sit back for once, because we never do that, and just be fans – experiencing it the same way everyone else does. So that’s why we wanted it to be first-time viewing for us, for the most part.

“The only exception was Dallas Green. Our management got hold of it and it was early on in the recruitment process for this thing. It gave us confidence that we’d pull this whole thing off – I was really moved by it. I also loved the flamenco version of Black Gives Way to Blue, which came during the end credits.

“There was so much talent. We were very moved that these artists got involved, especially given the fact that there’s a pandemic on. Nobody was traveling or touring.

“It was harder to get everyone together, some people lived in different parts of the country, and yet they managed to assemble an all-star gathering of friends from like-minded bands. It was such an undertaking but it came out great!”

- Neon Christ release a deluxe edition of the 1984 sessions on June 12 via Southern Lord and DVL Recordings.

Amit has been writing for titles like Total Guitar, MusicRadar and Guitar World for over a decade and counts Richie Kotzen, Guthrie Govan and Jeff Beck among his primary influences as a guitar player. He's worked for magazines like Kerrang!, Metal Hammer, Classic Rock, Prog, Record Collector, Planet Rock, Rhythm and Bass Player, as well as newspapers like Metro and The Independent, interviewing everyone from Ozzy Osbourne and Lemmy to Slash and Jimmy Page, and once even traded solos with a member of Slayer on a track released internationally. As a session guitarist, he's played alongside members of Judas Priest and Uriah Heep in London ensemble Metalworks, as well as handled lead guitars for legends like Glen Matlock (Sex Pistols, The Faces) and Stu Hamm (Steve Vai, Joe Satriani, G3).