DNA of Tone: A Guide to the Basic Building Blocks Behind Jazz, Blues, Metal and Classic Rock Guitar Sounds

A few basic guidelines to consider when putting together a rig, whether you want to play jazz, blues, classic rock or metal.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Creative individuals tend to view the term “formula” as a dirty word, but most styles of music have specific parameters and characteristics that define them. For several of the most common styles of popular music, the style itself is defined predominantly by the guitar tone. For example, while punk and metal rely on heavily distorted guitar, most music fans can tell the difference between the two as much as by how the guitar sounds as by how it is played.

While it would be nice to be able to buy just one guitar rig that could be used for every style of music, the reality is that guitarists usually need to rely on separate sets of building blocks to play various styles. Below are a few basic guidelines to consider when putting together a rig, whether you want to play jazz, blues, classic rock or metal.

JAZZ

The generally preferred tone for traditional jazz is not too far from the sound of an archtop hollowbody acoustic guitar, only amplified to louder volume output to be heard over other instruments like drums, horns and electric bass and keyboards. The tonal palette for jazz expanded during the early Seventies with the emergence of jazz-rock fusion with guitar tones that would not be out of place on hard rock records of the day, and during the late Seventies and Eighties many players took tonal cues from funk and pop productions. However, over the last few decades most jazz guitarists have returned to more traditional tones as a base.

The ideal electric guitar for traditional jazz is an archtop hollowbody with a “floating” pickup attached the end of the fingerboard instead of the top, to allow the top to vibrate and resonate with its full acoustic potential. Flatwound strings are also preferred. Archtop hollowbodies with top-mounted pickups and controls are also popular, as are semi-hollow models. While many jazz guitarists like Bill Frisell, Wayne Krantz, Mike Stern and others prefer solidbody electrics, the number of players who prefer solidbodies is a smaller group.

For amplification, a powerful amp with plenty of clean headroom is preferred. The classic tube-driven Fender Twin Reverb is a good choice, as are solid-state amps like the Roland JC-120, Polytone Mini Brute and Henriksen Jazz Amp. Good traditional jazz guitar tone should be clear, warm, rich and dynamic with emphasized midrange and bass and just enough treble to keep the tone from being muddy and flat.

An overdrive or clean boost pedal is ideal for players who lean toward fusion or just want a little rock or blues personality. Other effects are generally used sparingly, although crisp, shimmering chorus is often used for rhythm tones. The Eventide H9 and Mod Factor, TC Electronic Corona or various Boss chorus pedals (as well as the chorus effect in Roland Jazz Chorus amps) are all popular choices.

BLUES

Back in the early days of the electric guitar, jazz and country players demanded only the cleanest tones from their amplifiers, and anything beyond the slightest hint of overdrive was considered vulgar and undesirable. Whether it was intentional preference or just a tendency toward playing as loud as possible, blues guitarists were the first to adopt the sound of a distorted amp during the early Fifties. The raunchy tones of a primitive amp circuit pushed well into overdrive inspired British blues and rock players during the Sixties, who developed their own signature blues tones using British amps.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Pretty much any style of electric guitar is acceptable for playing blues, including an archtop hollowbody (like T-Bone Walker and Duke Robillard), semi-hollow (like B.B. and Freddie King), or solidbody (Muddy Waters, Buddy Guy, Stevie Ray Vaughan, you name it). Even cheap pawnshop guitars and shred axes are acceptable, although an eight-string baritone may be pushing things too far. While Stevie Ray Vaughan was known for using exceptionally heavy strings in his quest for the fattest tone, most blues guitarists prefer lighter-gauge strings that make it easier to bend notes.

When it comes to amps, Fender is the standard for American blues and Marshall reigns supreme for Sixties-style British blues. Fender tweed amps are particularly ideal for their harmonically rich overdrive and horn-like midrange, but more powerful later Fender models like the Deluxe Reverb and Super Reverb also are beloved. The most ideal Marshalls for blues are ones with early, pre-master volume circuits. Dozens of amp builders from large corporations to small boutique artisans offer a wide variety of amps based on Fender and Marshall circuits that are good alternatives.

Like jazz guitarists, blues guitarists generally prefer to use only a handful of effects. Again, overdrive and clean boost pedals are popular, but even a good distortion pedal isn’t entirely out of the question. Other useful effects include tremolo and reverb if the amp doesn’t have these features, and a wah pedal is acceptable both as a midrange filter/boost or for typical sweeping wah effects. For modern blues à la Gary Clark Jr. or the Black Keys, an octave-up pedal is a popular effect.

Classic rock—which loosely spans a period from the late Sixties through the early Eighties—has by far the broadest tonal palette of the genres discussed here, which means that there are many more options to choose from and consider. Guitarists from this era tended to prefer distortion tones that were more saturated than typical blues overdrive tones, and thanks to more powerful amp designs players were able to achieve this with tighter, more focused bass as well. However, modern multi-stage gain circuits were just in their infancy during the late Seventies and distortion pedal circuits were not as refined, so the tones are more “polite” than the metal tones that became the norm shortly after the birth of thrash metal.

Like the blues, almost any style of electric guitar is acceptable, although a solidbody guitar is usually preferred, followed by semi hollow and in a few rare instances a hollowbody archtop (à la Ted Nugent or Steve Howe). The classic triumvirate—Gibson Les Paul, Fender Stratocaster and Fender Telecaster—are reliable choices that can handle most classic rock tones, but variations on these designs as well as the Gibson Explorer, Flying V and SG are good too.

Distorted classic rock guitar tone is more about power amp distortion than preamp gain, so you’ll want either a non-master volume amp (if you don’t mind the excess volume levels needed to push these amps to the sweet spot) or use a high-gain amp with the volume control cranked all the way up and the gain dialed up only moderately. Hundreds of great classic rock recordings were done with small Fender tweed combos like the Deluxe and Princeton, which deliver harmonically rich distortion but at the expense of loose, flabby bass. Fender, Hiwatt, Marshall and Vox amps were the most common choices back in the day, and any of today’s amps based on those classic models from the Seventies are good alternatives.

When it comes to effects, pretty much anything goes, including fuzz, compression, rotating speaker/Leslie cabinets, delay/echo (particularly tape delay), modulation effects like phase shifting, flanging, chorus and tremolo. A graphic EQ pedal with several frequencies boosted (like midrange) can push a moderately overdriven amp into distortion, and hundreds of distortion pedals can transform any clean amp into a distorted classic rock beast—just go easy on the gain and try to retain some of the natural clang of the strings.

METAL

While the definition of metal has changed since the earliest days when Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin pioneered the genre (in fact, by today’s standards Zeppelin would not be considered metal at all), the primary, defining sound of metal has always remained a heavily distorted electric guitar. Over the years the amount of distortion has crept up significantly, thanks to advances in high-gain amp circuits and stomp box technology.

Because excess distortion and volume is the goal, a solidbody guitar is the preferred choice since semi-hollow and hollowbody guitars tend to feed back when played at the boosted levels of gain for metal. Standard six-string guitars are still the most common, but increasingly metal guitarists are playing seven- or eight-string guitars, baritones or six-strings with extended scale lengths that can better accommodate dropped tunings and heavier string gauges.

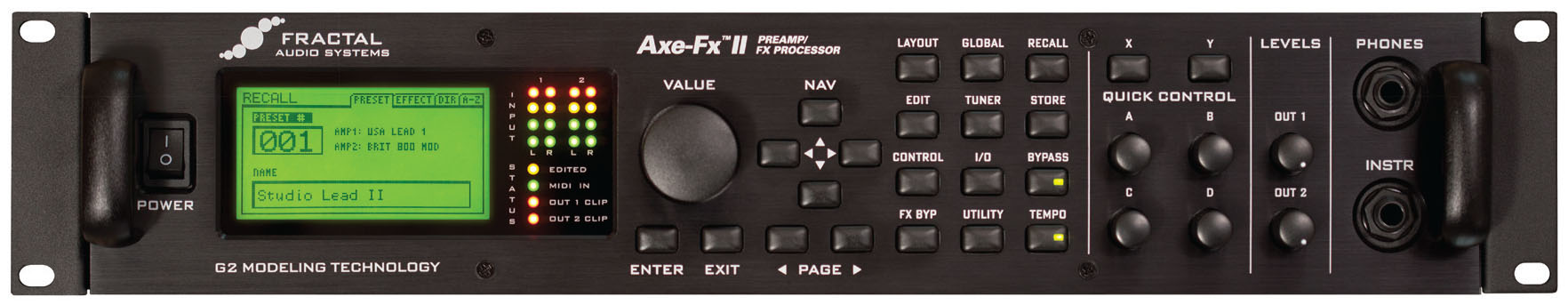

A multitude of high-gain amps that produce modern metal tones are available from companies that include Blackstar, Bogner, Diamond, Diezel, Egnater, Engl, EVH, Friedman, Fryette, Hughes & Kettner, Line 6, Marshall, Mesa/Boogie, Orange, Peavey, Randall, Soldano and dozens of other manufacturers. Tube amps are still dominant, but many players prefer the tighter tone and fast attack of solid-state amps, and an increasing amount of metal guitarists are using digital modeling products such as the Fractal Audio Axe-Fx II, Kemper Profiling Amplifier and Positive Grid Bias Amp.

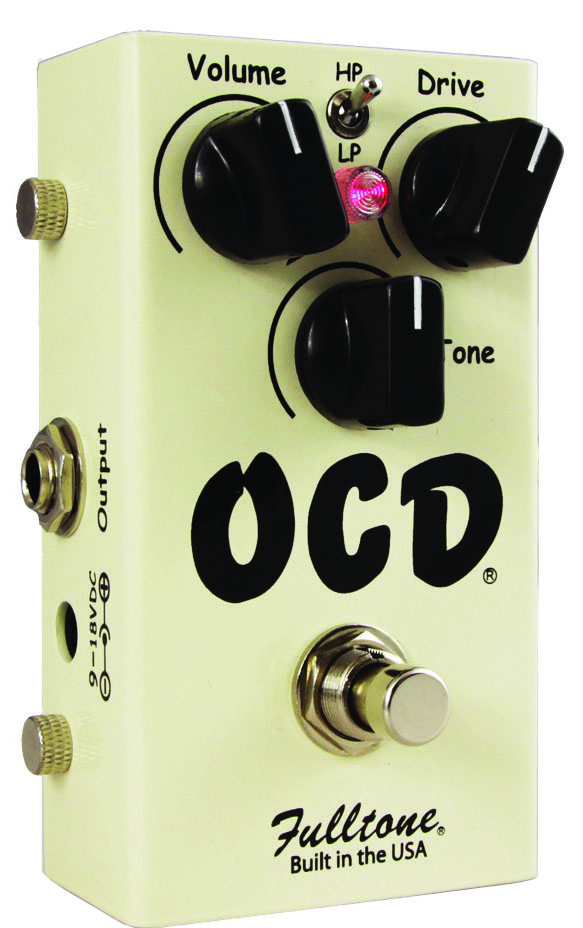

Many great distortion pedals are now available that can produce credible metal tones through almost any amp. There are literally hundreds of options, with the Electro-Harmonix Metal Muff, Friedman BE-OD, MXR EVH 5150 Overdrive, MXR Fullbore Metal and TC Electronic Dark Matter being among the more popular choices. A good overdrive or clean boost pedal like a Boss SD-1 Super Overdrive, Electro-Harmonic Soul Food, Full-tone OCD, Ibanez TS9 Tube Screamer or Klon KTR is ideal for players who want to boost solos.

To minimize noise and tighten rhythm playing, a noise gate/suppressor is essential. Because high-gain distortion tends to result in undefined, smeared tone when using reverb, a delay pedal is a better alternative for creating room- or hall-like ambience while preserving clarity and definition. A graphic or parametric EQ is also helpful for sculpting tones with greater precision, particularly when cutting midrange.

Chris is the co-author of Eruption - Conversations with Eddie Van Halen. He is a 40-year music industry veteran who started at Boardwalk Entertainment (Joan Jett, Night Ranger) and Roland US before becoming a guitar journalist in 1991. He has interviewed more than 600 artists, written more than 1,400 product reviews and contributed to Jeff Beck’s Beck 01: Hot Rods and Rock & Roll and Eric Clapton’s Six String Stories.