Adding Dynamic Appeal to Your Power Chords with Intervals and Dyads

Add some flavor and variety to your power chord progressions.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Power chords, once your fingers are comfortable with the stretching, are mind-numbingly simple.

That's not a bad thing and I wouldn't say that power chords are "cheap" or "too easy."

That's dumb.

Because they get the job done, right? So why wouldn't we use them? They’re functional and adequate to the task.

In the right context, power chords are a beautiful thing. When music demands a heavy, smooth and easy-to-digest chord progression (like in modern rock, pop, metal, etc.), a root note, a consonant interval (perfect fifth) and perhaps an octave thrown in for good measure, are all you really need.

We can play as many chords as we want all using the same shape; just shift frets or strings.

But what if we wanted to dress things up a little bit? What if we wanted to make our power chords more dynamic and melodic?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Adding some flavor and variety to your power chord progressions can really take your playing up a notch and set you apart. It's an especially handy technique for those who fill the role of both a lead and rhythm guitar player.

There are two primary techniques you can use to do it; intervals and dyads. Let’s cover intervals first.

First Technique: Add Major or Minor Intervals

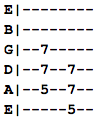

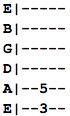

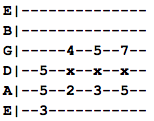

Assume you're playing a chord progression in a major key. Even better, let's just say you're going from D to A. Tabbing it out would look like this:

What if you wanted to add some melody or even just variety? We can use major intervals to do so, since we're theoretically dealing with two major chords. So where do we put these intervals?

You'll need to target areas where you have long pauses or holds on a single chord. So in this situation, we can assume (for illustrative purposes) that the D chord gets held for a short few beats, while the A chord is held longer.

That means the A chord is where we can move a bit more and add some creative intervals.

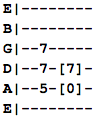

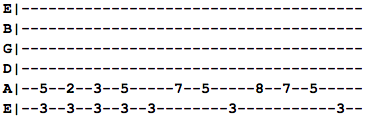

Use the open A note to play your second A chord (bracketed).

We can now start adding intervals to our A chord. Here are a few options:

It's a simple, but effective, strategy.

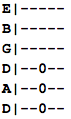

You can employ the same interval shifts with any other power chord. Say we don't have an open chord to work with, like in the case of this G:

We can still add intervals by shifting the note at the fifth fret, currently a perfect fifth, in relation to the root note at the third fret.

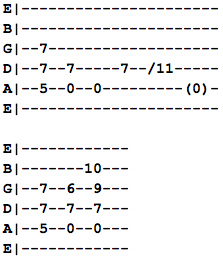

Here's what I came up with.

As you can see, the only note that needs to change is the interval of the root. The root note itself doesn't move.

That means you can use this tactic as often as you want within any power chord in any given progression.

If the progression contains minor chords, you'll have to make sure to hit notes that resolve to a minor tune. But that will come with habit, muscle memory and time.

Second Technique: Add Octave Dyads

A second strategy is to use simple, two-note dyads to add short melodies over power chords. This has become a widely used technique in the post-grunge era and has been typified by many modern guitarists.

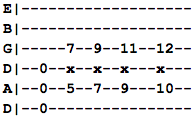

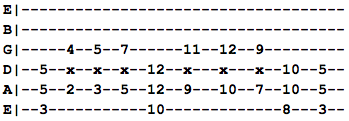

To illustrate this example, I find it best to start with an open D chord in drop-D, like the following tab:

Start with your D root note on the second string (fifth fret), add its corresponding octave (third string, seventh fret) and reapply some of the intervals we already covered by simply moving the octave shape up the fretboard.

We can apply the same principle with the G chord as our base and the 2-3-5 fret climb is our melody.

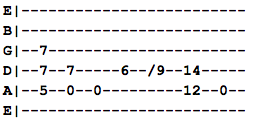

Once you get comfortable, start planting these runs in between chords. Like this:

Not only does this break the monotony of a chord progression, but it adds some melodic flavor to what is otherwise a one-dimensional and linear sound.

Because sometimes a guitar player needs to handle both rhythm and lead, especially today when many groups employ only one guitarist. Being able to play heavy, while also having enough skill and musical awareness to add melody and variety to your chord progressions makes you a far more valuable musician.

And while they aren't all you need to accomplish that, dyadic octaves and intervals can give you a lot of mileage as they're excellent tools to work with.

If you play a lot of power chords you shouldn’t feel bad about it.

Just learn how to make them count.

Robert Kittleberger is the founder and editor of Guitar Chalk. You can get in touch with him here or via Twitter.

Flickr Commons Image Courtesy of maury.mccown

Bobby is the founder of Guitar Chalk, and responsible for developing most of its content. He has worked with leading guitar industry companies including Sweetwater, Ultimate Guitar, Seymour Duncan, PRS, and many others.