Joe Bonamassa teaches you how to play The Ballad of John Henry

John Henry is a a setlist favorite that even Bonamassa himself sometimes plays incorrectly, but this, the blues-rock maestro promises, is the definitive way to play it

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In this lesson, I'd like to demonstrate how to play one of my more well-known tunes, The Ballad of John Henry. This song was written in 45 minutes (I wish they all took shape that quickly!) and appeared as the opening track of my 2009 album of the same name.

I’ve recorded a few different versions of the song over the years, so I’d like to show you the “Inside Baseball” details about how to play it correctly. I don’t always play it correctly myself, but this is how it’s supposed to be played!

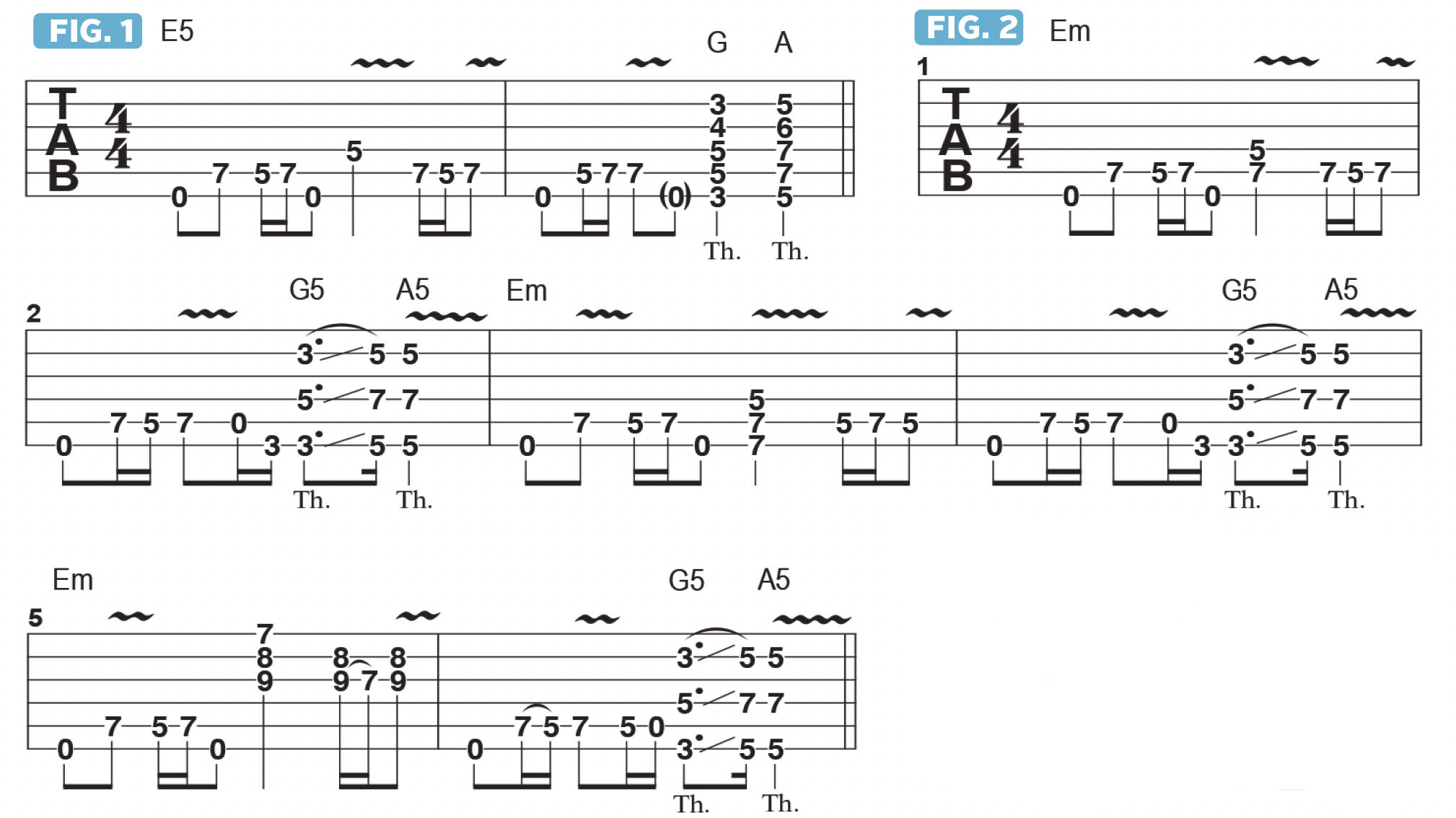

Figure 1 depicts the tune’s primary riff. Played in the key of E minor, it’s a simple, two-bar riff that’s played on the bottom two strings. It’s based on the E minor pentatonic scale (E, G, A, B, D) and culminates with G and A chords before repeating.

Notice that I like moving between my index finger and pinkie when playing the two-note figure on the 5th string, as I find this to be the most comfortable and natural way to fret this riff.

Something you might not easily hear within the full band mix is the subtle references to the Em chord voicings that lurk in the background, and I only occasionally incorporate Em triads into this primary lick.

As shown in bar 1 of Figure 2, instead of playing a single G note on beat 3, I instead play a two-note E-G dyad, making clear reference to the essential Em tonality via the root note and minor 3rd.

In bar 3, I fret a fuller-sounding Em triad that includes the 5th, B, as the lowest note in the chord, raking across the three strings from low to high and adding some finger vibrato for dramatic effect.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

In bar 5, this three-note Em triad is moved up to the top three strings, sounded as E-G-B on beat 3, with vibrato added once again, which gives it a meaner, bluesier sound. Reference to the minor chord is maintained in the subsequent lick, as I bring the high G note along for the ride when sounding the E and D notes below it.

Adding the Em triad to the single-note riff creates an ominous feel that lends the song a darker vibe, which I really like. But it’s not an obvious minor sound; you could just play the single-note version of the riff every time, and it will sound fine. I like to include the minor triads here and there because, while you may not know where it’s coming from, in a subtle way there is a low, harmonic resonance added.

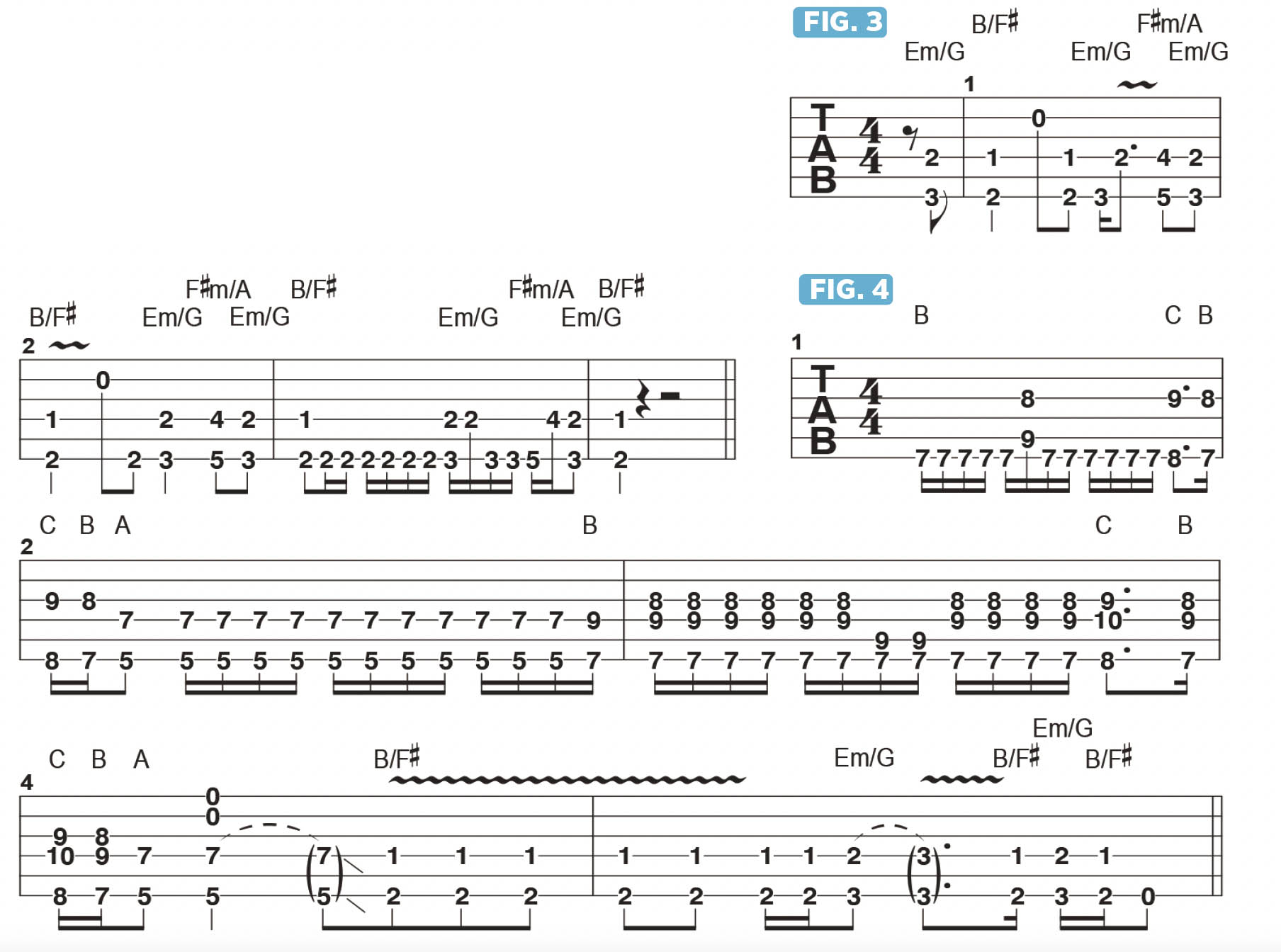

I’m a fan of flipping triads around, as I do here by adding the 5th, B, as the lowest note in an Em triad. Figure 3 offers another good example of this approach. Starting with a low G note and E, a 6th above, this two-note chord makes reference to Em/G.

When I move down one fret, the resultant F# and D# notes allude to a B/F# chord, which is not unlike what Jimmy Page did, in Since I’ve Been Loving You, in the key of C minor. Sliding this shape around gives me access to a variety of heavy-sounding chords built from just two notes. Figure 4 elaborates on this approach.

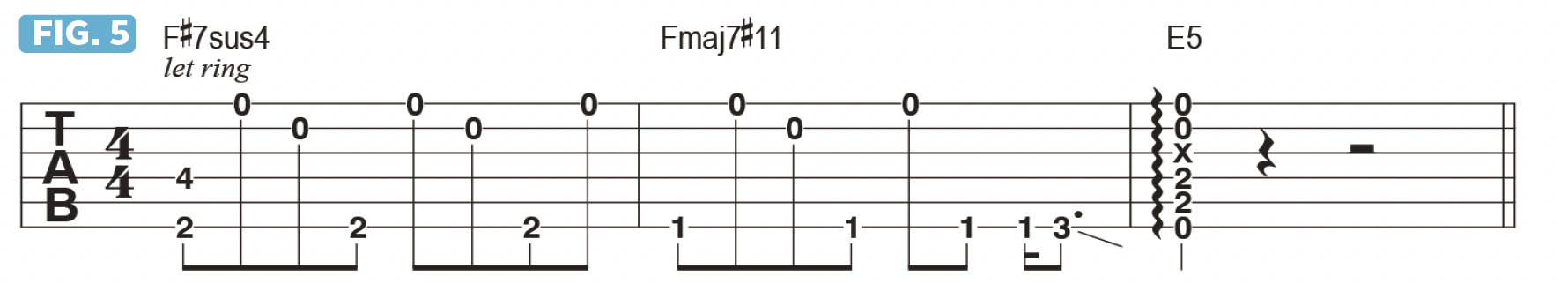

No look at John Henry would be complete without a look at the rich-sounding F#7sus4 - Fmaj7#11 move that closes out the progression, as shown in Figure 5.

- Time Clocks is out now via J&R Adventures.

Joe Bonamassa is one of the world’s most popular and successful blues-rock guitarists – not to mention a top producer and de facto ambassador of the blues (and of the guitar in general).