Learn 5 guitar chords that evoke the golden age of Hollywood

These chords have an orchestral quality that radiates a certain silver screen soundtrack magic

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The term ‘soundtrack’ in our strapline doesn’t refer to music theory; it’s just a broad description of the type of chord we’re looking at in this feature.

These chords evoke the soundtracks from the ‘golden age’ of Hollywood, even though this type of music was usually an orchestral arrangement, rather than solo guitar. It’s an interesting challenge to see how harmonically detailed we can get with just six strings and even fewer fingers

Here, we’re looking at extended and altered chords based around minor, major and dominant 7ths. Often, the guitar need only extend up to the 7th and leave further extensions (9th, 11th or 13th) to the strings, woodwind or brass.

However, if you’ve ever listened to great players such as George Barnes, Martin Taylor and George Van Eps, then you’ll know that there’s no reason for the guitar not to get fully involved – and it’s interesting to note how different players stretch the boundaries to create interesting chords.

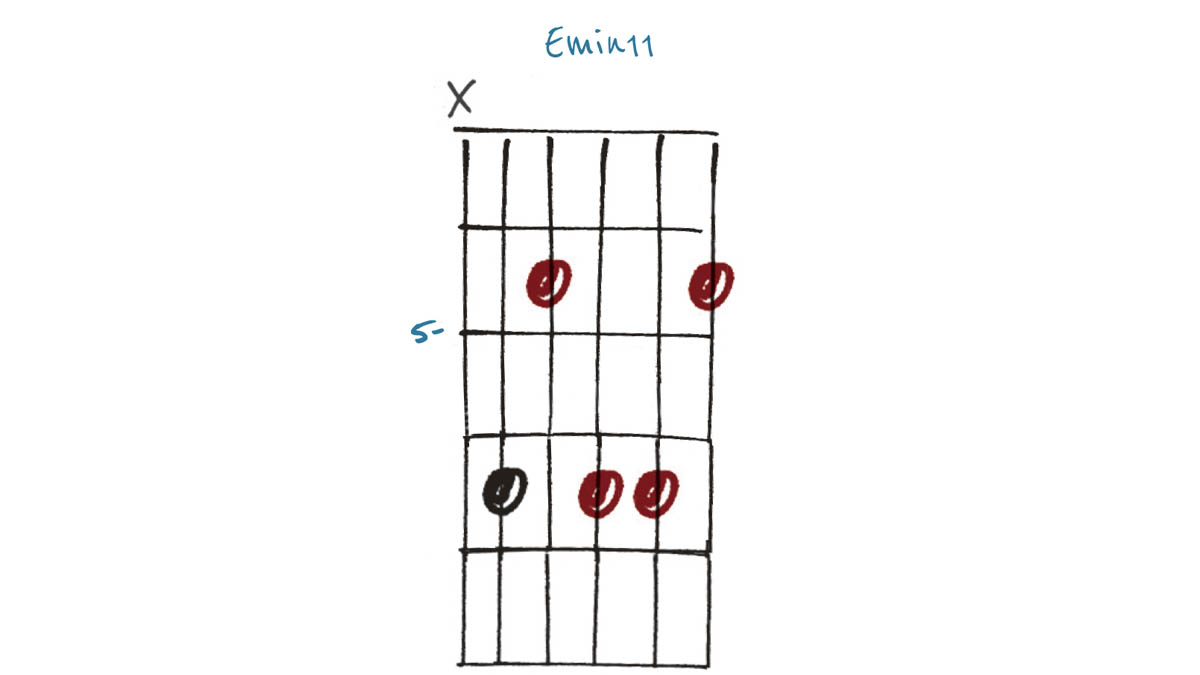

Example 1. Emin11

This Emin11 builds on an Em chord with a dominant 7th, adding the 9th (F#) and, of course, the 11th (A). Note the 5th (B) is missing. This is often the case on extended voicings such as this to aid clarity. It isn’t just a concession to the limited amount of fingers and strings available!

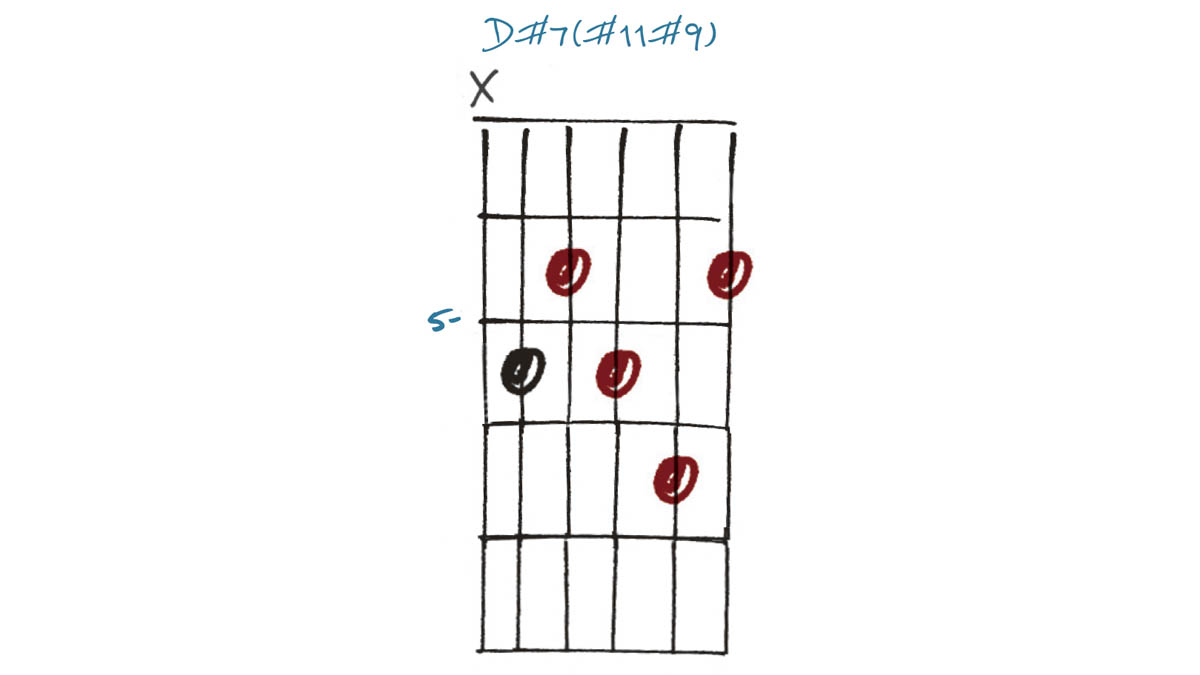

Example 2. D#7 (#11#9)

Moving just two fingers gives us a very different chord and mood. This D#7 (#11#9) could be described as the ‘tension’ before the ‘resolve’ of a subsequent chord. Or to underscore a dramatic moment in a film, maybe it could be left to hang like a less benign version of a sus chord.

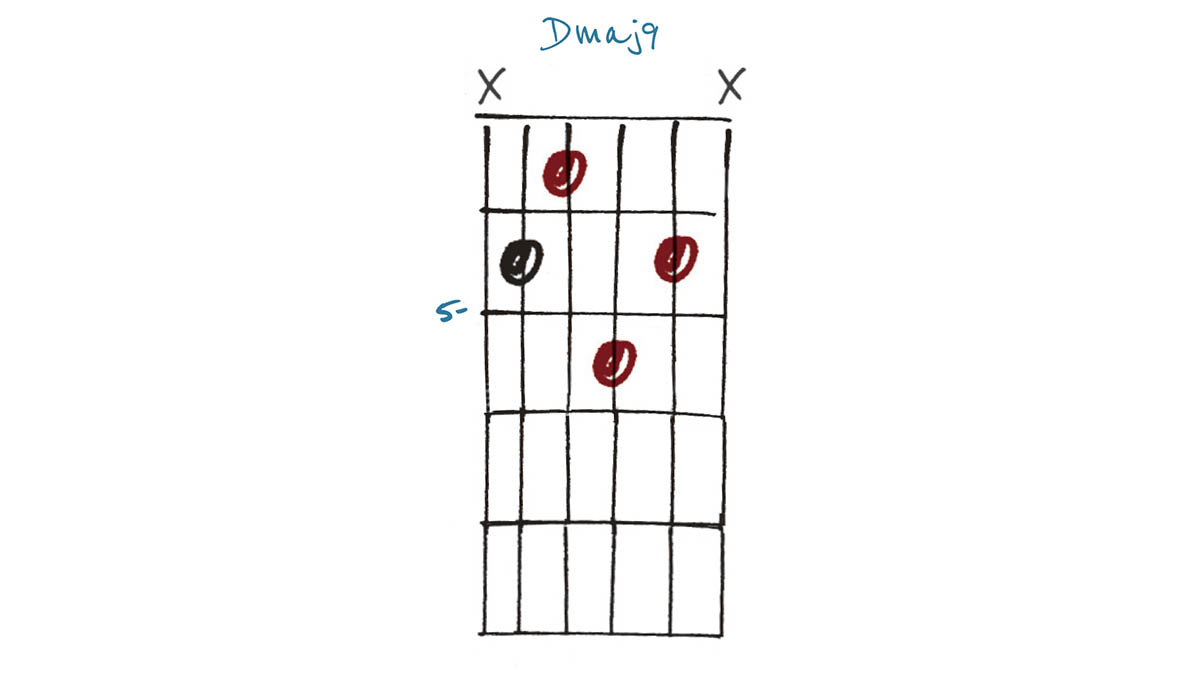

Example 3. Dmaj9

This Dmaj9 is a great example of where you could go to resolve after Example 2. As with Example 1, we have no 5th (A in this case). From low to high we have: D (root) F#(maj3rd) C#(maj7th) F#(9th). The ‘major’ part of the name differentiates this from a D9, or dominant 9th.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

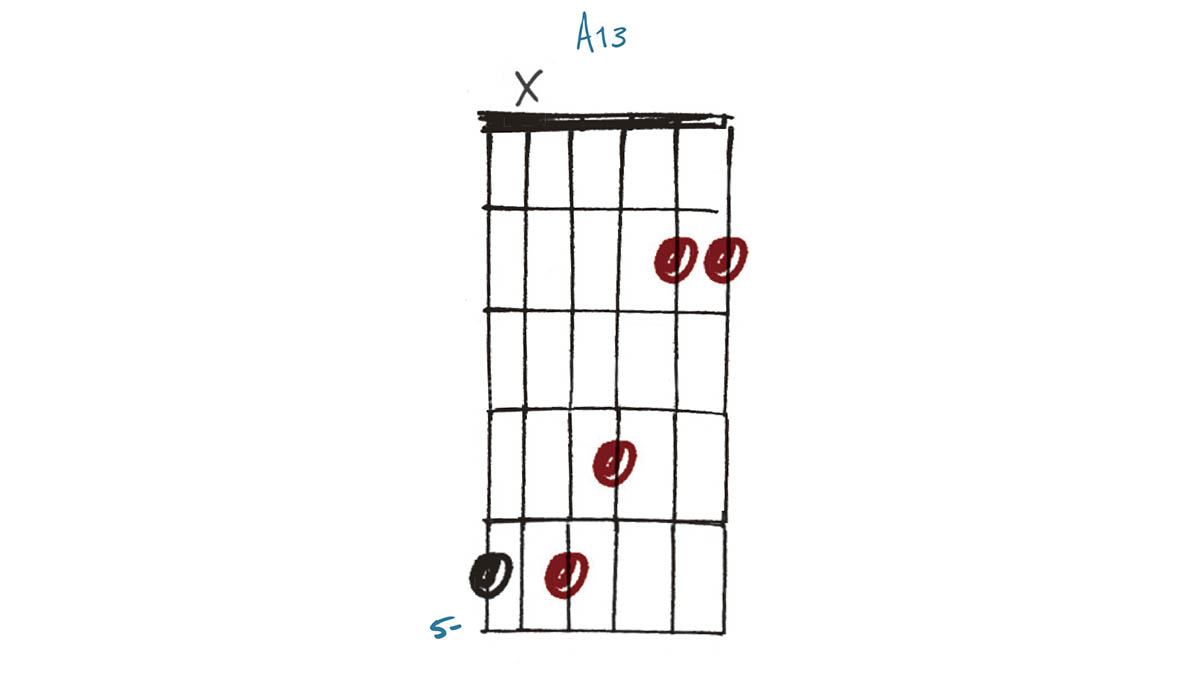

Example 4. A13

You’ll need to be sitting comfortably to manage this rather ‘stretchy’ A13, but the lovely way it lays out the extensions makes it worthwhile. You could use the open fifth string as your root (A) in this position, but then you’d lose the ability to move it around. I’ve chosen this position/key because it fits so well with the other chords.

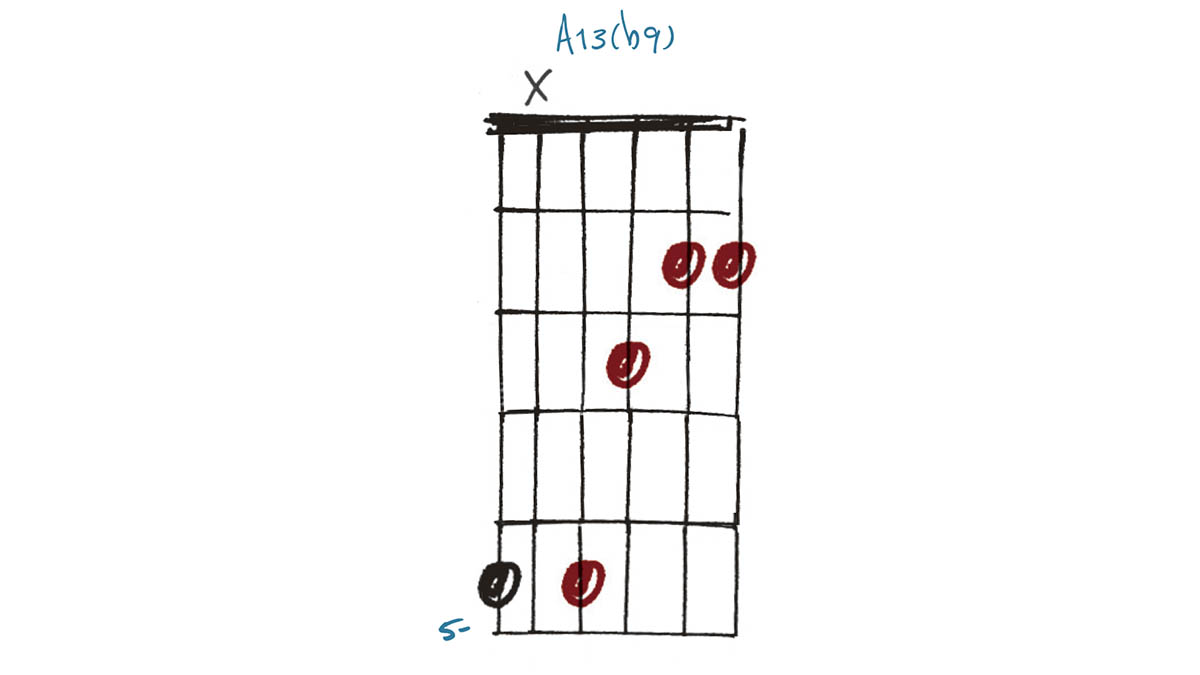

Example 5. A13(b9)

A slight shift within the chord gives this A13(b9). Again, using this voicing with the muted fifth string means you can shift it to play in any key. It’s easier as you move up the fretboard – and don’t forget you can make things easier by omitting the root if there’s a bass player to cover it!

As well as a longtime contributor to Guitarist and Guitar Techniques, Richard is Tony Hadley’s longstanding guitarist, and has worked with everyone from Roger Daltrey to Ronan Keating.