Achieving Absolute Fretboard Mastery, Part 5

Learn a really easy way to expand your pentatonic major and pentatonic minor into diatonic scales.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

This month, I’m going to show you a really easy way to expand your pentatonic major and pentatonic minor into what we refer to as diatonic scales, the "do re me fa so la ti do" scale, which in turn becomes your modes.

The goal this month is not to talk about the theory behind them, although I will be doing that in the next month or two. It’s to get you adding the pitches and exploring these notes, aurally, as well as using them in your phrasing.

So let me show you what I’m talking about!

Article continues belowLet’s go to the fifth fret of the sixth string, for the A minor pentatonic and the C major pentatonic.

When I was growing up, in my mind, minor was always starting with my first finger, and major was always starting with my pinky. So if we think about it in this one position, we’re playing in A minor pentatonic and C major pentatonic. They’re the same thing, the difference being the notes you’re going to emphasize in your solo that make it sound A minor and/or C major. I’m going to treat this like minor pentatonic to begin with.

I will go to the A and play A, C, D, E and G. Those are my five notes that create a pentatonic — penta meaning five, of course. The pentatonic is a great scale, because pretty much any note you hit is going to fit anywhere. But the downside to pentatonic for a lot of people is that it doesn’t function very well melodically. The notes we’re going to add today will make a huge difference to the way things sound.

Take the first two strings of the pentatonic scale, the A minor pentatonic, and play 5, 8, 5, 8. Then I’m going to add in the sixth fret of the second string, and then the seventh fret of the first string. So you’re taking the 5, 8 and you’re simply expanding it to add the 6, and the first string, the seventh fret.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

In adding those, the first thing that happens is you get half steps. In the pentatonic scales, you never get a half step. And those half steps begin to sound very melodic.

Diatonic scales, which are the major scales, are the catalyst for all music. When we add these two notes, we get a diatonic scale. I also can start on C. So if you think about it, what I’m doing is playing an A minor pentatonic, but I’m emphasizing the note C, so it gives me the C major pentatonic. So I’m starting on C, and I’m playing the same notes, but all of a sudden it gives you that "do re me fa so la ti do" sound. Whether you’re in minor or major pentatonic, if you add in those two notes, it’ll be functional to give you a diatonic kind of sound.

Let’s label these notes. In pentatonic, we had five notes, which we called 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. But now that we’re in diatonic, we’ll count all the way to seven. I’m going to start on the C, on the fifth fret of the third string, and I’m going to play all of those notes, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and then 1 all over again.

What’s cool about the diatonic scales is when we talk about chords, and chord theory, which again we will be getting into in the next couple of months, chords are built off of what we would call a root fourth and fifth. What’s neat is that you can physically see the root, the third and the fifth, sitting right there. When people talk about seventh chords, they’re talking about the seventh note. So pentatonic is great for jamming and that sort of thing, but music theory is built off of the diatonic scale.

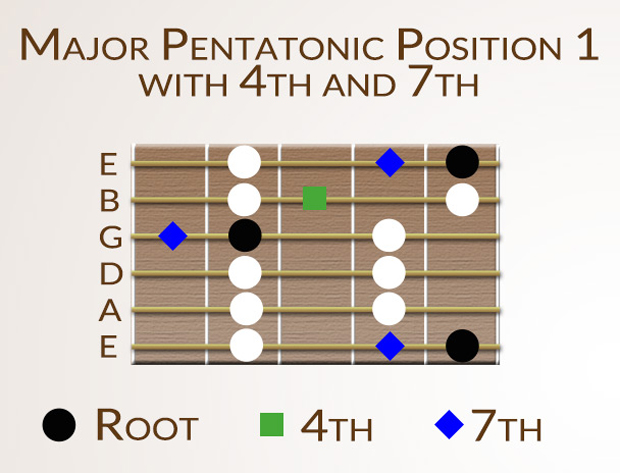

I want you to really start to be comfortable with moving through this. And just explore the sounds. Try it playing off of C. We’re adding 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. If we were looking at this major pentatonic scale sitting in C, and we added those two notes, we’d be adding the fourth and the seventh.

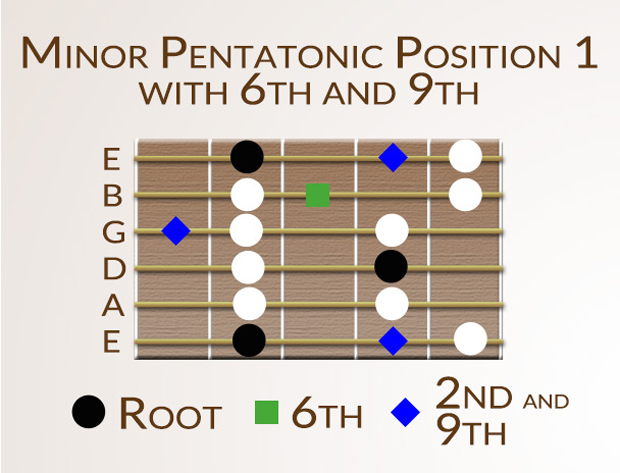

If we were looking at it from the minor perspective, come down here to A — so in the same position, but looking at A as the root, we’ll add in the sixth or the ninth. In order to show you that, I’m going to need to show you another octave. I’m going to take the seventh — the seventh fret of the first string — and I’m going to add it on the third string on the fourth fret. So I’m just lowering it down so you can see how it works. So I’m going to go to the A, and then the next few notes, ending on A again.

If I count it, I have 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 1.

The notes I’ve added to my pentatonic are a 2 and a 6. Remember, when you play C major and A minor pentatonic, you’re playing the same notes. If you were in A minor you’d be calling A "1." If you’re playing C major you’d call C "1." Again, I’m just giving them labels. When I’m adding it in again, you may call it a 9 — which is the same note as the 2.

What I want you to do is to start using the meandering we’ve been talking about (See the previous parts of this ongoing series under RELATED CONTENT above). And I want you to start using some of these notes. If I were playing an A minor — using A as my emphasis pitch — you’ll see that adding these notes makes it sound a lot more melodic. And, of course, you can use hammer-ons, pull-offs and slides, but really explore seeing the pentatonic and expand the pentatonic adding these two new notes.

A great exercise is to take a jam track, and even just record yourself playing a C chord — take your C. Or whatever — you start exploring the sound that makes. Record yourself playing an A minor, same thing. Just start exploring how that sounds. It’ll start sounding a lot less like blues. Can’t the sixth be a major sixth, or the ninth a flatted ninth? Yes, and that’s where the modes come from. That’s going to be further down the line.

Say you’re in a situation today, and you wanted to start using this, but you start playing all these notes and it starts sounding like too much – it almost sounds too melodic. A common thing people start to do in this kind of situation is to leave the second string note out, which is the sixth in minor, (or the fourth in major). We leave that note out and we just use the seventh. That’s a real nice way to apply this to a rock or metal situation, when you’re not exactly sure what to do. Just expand your pentatonic at this point by adding the ninth (if minor) or seventh (if major).

So, explore that, and next month we’re going to start expanding on the theory behind this. Take your jam tracks, and add those over the A major or C minor.

As you do it, use your meandering skills to add those in seamlessly and flawlessly. And then start taking the sixth (for A minor) or fourth (for C major) out, and see how that works over your jams.

Steve Stine is a longtime and sought-after guitar teacher who is professor of Modern Guitar Studies at North Dakota State University. Over the last 27 years, he has taught thousands of students, including established touring musicians, and released numerous video guitar lesson courses via established publishers. A resident of Fargo, North Dakota, today he is more accessible than ever before through the convenience of live online guitar lessons at Lessonface.com.