Melodic Phrasing and Playing Over Blues Changes

Learn some more about melodic phrasing from Testament's Alex Skolnick!

There’s a common thread that unites 20th-century jazz icons, such as Miles Davis, Charlie Parker and Louis Armstrong, and the numerous influential improvisers, including guitarists ranging from Charlie Christian to Pat Metheny, who’ve built upon their work. Like a genetic trait, this link is shared with American rock music from the Fifties (Chuck Berry, Elvis and Little Richard), Sixties British Invasion groups (the Beatles, Rolling Stones), psychedelic rock of the Seventies (Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin), early hard rock (Cream and Jimi Hendrix) and even pioneers of metal (Black Sabbath and AC/DC).

Like a shared gene, it’s sometimes obvious, sometimes not, yet always present.

Question: What could such divergent sounds possibly have in common? Answer: the blues.

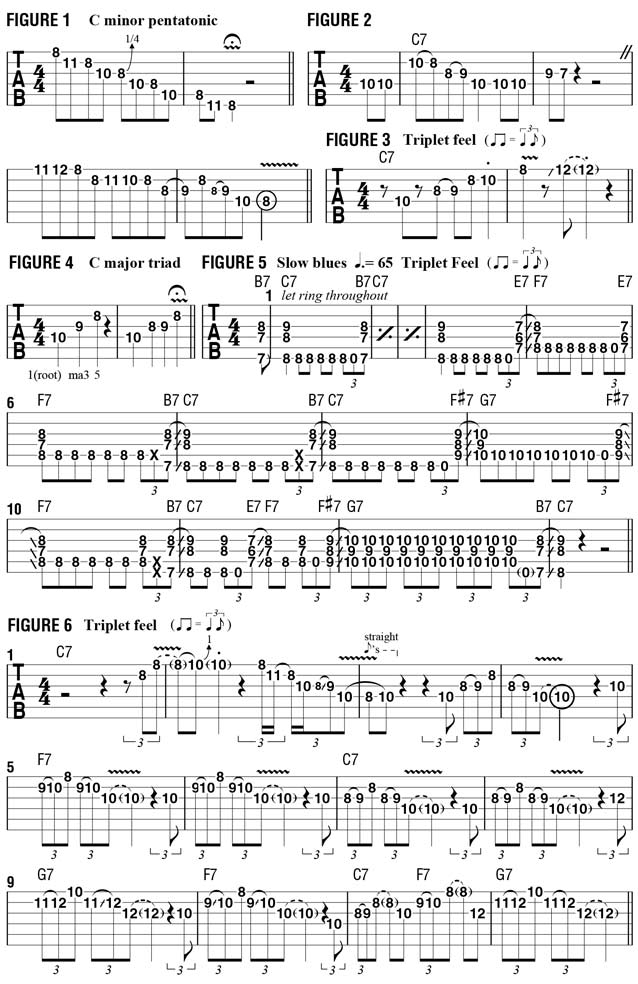

As guitarists, we’re often introduced to blues playing via two-notes-per-string patterns, such as the C minor pentatonic scale (C Eb F G Bb) illustrated in FIGURE 1. Not to underestimate the importance of this basic shape (after all, it is the source position of so many of our instrument’s most enduring licks, from Robert Johnson to Randy Rhoads), but in terms of playing an expressive solo with a blues flavor, this is a tiny component. Blues is based on a dominant seven chord. Things get more colorful (“blue”) when you emphasize a chord’s third and/or seventh with the minor third approaching the major third, either ascending or descending.

FIGURES 2 to 4 offer a few examples that accentuate the half-step move from minor to major third, akin to Quincy Jones’ “Theme from Sanford & Son,” George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue,” and a great hard bop melody, Horace Silver’s “Sister Sadie,” respectively. An example from rock that comes to mind is the single-note riff from the Beatles’ “Day Tripper.”

Blues rhythm guitar is often introduced to us via the types of blues-rock vamps heard in hard rock (like AC/DC’s “The Jack,”), classic rock (the Rolling Stones’ “Midnight Rambler”) and even punk (i.e. the Ramones’ “Rock ’n’ Roll High School”). As with lead playing, things become much more colorful when you emphasize the third and seventh. A nice blues vamp can be played with root-third-seventh shapes, what are known as “shell voicings,” that are approached from a half step below, as illustrated in FIGURE 5. Keep pumping the low bass notes of each chord to solidify the groove.

Your assignment now is in two parts:

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

1. Learn this vamp.

2. Learn the melodic line shown in FIGURE 6, which emphasizes the “color tones” of each chord (always approaching the major third from the minor third). If you feel adventurous, transpose these ideas to other keys. Listen for similar sounds on blues and jazz recordings. Most importantly, have fun!

Alex Skolnick photos from lesson video by Tom Couture | www.tomcouture.com

![Michael Shannon and Jason Narducy [on the white Telecaster] perform on Late Night with Seth Myers.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/eX6S7nn9FNajPVn3zcPXdM.jpg)