Joe Don Rooney of Rascal Flatts: "I Love Metal, Rock and Country — and I Like to Wrap It All Up Into One"

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Lovin’ Spoonful’s 1966 hit “Nashville Cats” pegged the city’s population of pickers at 1,352. Today, there’s a whole lot more, lured by Nashville’s booming country and rock industries and musician-friendly environment.

The cost of living is considerably lower than in New York and Los Angeles, and there are venues in every neighborhood. Nestled within each square mile are studios ranging from in-home operations like producer/guitarist Buddy Miller’s Dogtown to history-making enterprises like RCA Studio B, Ocean Way, Blackbird, Jack White’s Third Man and Dan Auerbach’s Easy Eye.

Nashville so zealously lives up to its “Music City U.S.A.” moniker that young musicians with GIT- and Berklee-level chops arrive daily.

Fifteen years ago, Joe Don Rooney was one of those arrivals, a fresh-faced kid from small-town Oklahoma via small-town Arkansas, seeking his fortune in the post–Garth Brooks country boom that has now blown into a firestorm.

Since 1999, Rooney has helped fan those flames as a member of Rascal Flatts, whose eight albums have sold 20 million copies, put 35 songs on the pop charts and delivered more than 50 country singles, including 28 Top 10s. The group’s decade of number-ones spans 2002’s “These Days” to “Banjo” from last year’s Changed. All that has made Rooney and his Flatts-mates, bassist Jay DeMarcus and aptly named singer Gary LeVox, into superstars.

But there’s more to Guitar World’s newest columnist [See his three Rockin' the Country lesson videos here] than the sum of his hits. In a city full of monster guitarists, Rooney is a dragon slayer. Raised on everything from Merle Haggard to Mötley Crüe to Metallica, he is a living compendium of hot licks and fat tones. And he’s learned the tricks of applying them to a genre governed by the rules of lyrics-based song craft, even while bending those rules to sometimes-deranged angles.

Rooney revealed just how far he’s willing to go on Rascal Flatts’ last tour, where he played a Theremin that he controlled by moving his six-string’s body and blew the minds of fans accustomed to a very different kind of air guitar. For more evidence, listen to the crescendo of his band’s bravura “She’d Be California,” where he conjures up Pete Townshend, hair metal and hot-doggin’ blues-rock in 60 seconds of howling nirvana. For the record, the latter, with a capitol N, is also in his wheelhouse of influences.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Country music has evolved more over the past 20 years than in its entire history,” Rooney says over a latte at Fido, a bustling Nashville coffeehouse where sightings of stars like Sheryl Crow, Emmylou Harris and Kings of Leon’s Followill brothers are as common as the sound of hissing espresso machines. “It’s got a lot of rock and pop qualities. When I was growing up in Oklahoma, my dad, Wendell, told me to play country music and my brother and sisters told me to play rock and roll. That was a dichotomy then, but today I can keep them all happy.”

Rooney is too humble to admit the role he and Rascal Flatts have played in the genre’s transformation. Likewise, he credits überproducer/guitar wrangler/songwriter Dann Huff for helping him achieve the big tones, brilliant textural pads and overall blend of the wily and the wild that characterize his playing.

“The bottom line for me is that it’s all about freedom,” Rooney explains. “I love me some heavy metal. I love rock. I love country. And I like to wrap it all up into one. I don’t see why there has to be a boundary. As a player, I need to think outside the box—especially within the structure of a great tune—and be expressive in my own way.”

GUITAR WORLD: Country music is extremely lyrics driven. How does that affect what you choose to play?

The lyrics are exactly what determine your tone for a solo. Although you don’t want to steal the song’s thunder, you still want to be heard and be creatively expressive so the listener doesn’t start a conversation or turn the dial. That balance is not easy.

If its a slower number, like a 6/8 ballad, and it’s got some motion, like a soaring melody or chorus, the guitar solo shouldn’t soar. When a song is balls to the wall, you can just let ’er rip. On Changed, there are some songs I used an old Gretsch Country Gentleman on, and it was heavy. A lot of players wouldn’t opt for that guitar to rock out, since that’s not what it’s known for. That’s why it’s important to try things outside the box. There’s such a “splatty-ness” that you can get to the Country Gentleman’s tones through a Bogner or Matchless. I also used that combination for a lot of pads we put behind the chords.

How do you approach pads? Many Rascal Flatts ballads—“Changed” and “Here Comes Goodbye” from Unstoppable are good examples—feature vibrant textural guitar parts and tones that sustain like David Gilmour’s.

To give credit where it’s due, [session guitarist] Tom Bukovac may have played the slide pad on “Changed.” We both tracked pads and rhythm parts all over that album, although I know I played the chords and supported myself on the solo for that song. The idea, again, is to support the song. Something has to occupy that space and improve it, so a pad’s got to be just right. And with a song where the melody’s that good, you need to give it the space it deserves.

Man, I love David Gilmour. He’s a singer on the guitar. That’s an idea that Dann introduced me to when he produced Rascal Flatts for the first time, for our fourth album, Me and My Gang. I was getting ready to cut a solo and he said, “Okay, set your guitar down. Let’s find out where you want to go by singing it, and then plug in and play.” That is such a good idea. Otherwise, your fingers want to go somewhere familiar. Once you start seriously thinking about melody—the concept of singing with the guitar—that opens you up to places you’ve never been before.

How can a guitarist make a mark as a player without compromising the verses and choruses of a song?

I preach countermelody. In country, where the singer gets “front and center,” us poor guitar players don’t always get respect. It irks me when people start talking during the solo, so it’s a challenge to keep them from doing that without ruining the vibe of the song. That’s why countermelody is so important. It creates another hook and gets your playing noticed while supporting the song.

I understand that Dann Huff was instrumental in getting approval for you and Jay to actually play on Rascal Flatts’ albums?

Our first producers were Mark Bright and Marty Williams. When we got with them to record our debut in 1999, they had a bunch of studio cats lined up to play, which is how it works in Nashville.

Since success was sweeping us up, Jay and me thought we’d play the game a little bit. We were fresh young kids trying to make it, and these guys were experienced. But after a couple years, we were like, “Hey, come check us out live. We really do play! Give us a shot, and if we fall on our faces, you can go back to the studio players.”

Since Dann was a proponent of our playing, Jay and I sought his advice. He said, “I can make the phone call.” He called the label and said that we needed to play on the third album, and that when we did it was probably going to open up a new door in Rascal Flatts. Mark and Marty were cool and listened to Dann, and after that, we did every other album with Dann. So Dann is definitely a mentor. He was also one of my heroes before I moved to Nashville, because of the great work he’d done as a singer, writer, guitarist and producer.

How did you fall in love with guitar?

I was 11 when I got my first one—a Seafoam Green American Standard Tele. I enjoyed music. My mom has eight brothers, and they all sang and played. Every summer, her family would have reunions and play, and my dad always fit in. He played country music and Top 40 in the bars back home.

I used to stay up all night trying to learn new licks off of Arlen Roth videos—which set the bar—or Brett Mason or Albert Lee licks, and then at 7 A.M. I’d catch the bus to school. Luckily, Picher, Oklahoma, is a small town, so it wasn’t a long ride.

By 14 or 15, I was lugging my Tele, my old Fender Twin with JBL speakers and a distortion pedal to rock clubs to play. My dad helped me put wheels on the Twin, which changed the sound a little bit. After I moved to Eureka Springs, Arkansas, at 18 to play in a family theater, I had a Seymour Duncan Hot Stack installed under the pickguard between the neck and bridge pickups so I could do all that Brett Mason stuff when his chicken pickin’ and other licks were so popular in Nashville.

I had one of my tone pots replaced with a pot that could blend the Hot Stack in. I had that guitar until right before Rascal Flatts formed. It got stolen out of my truck after I moved to Nashville, along with a set of golf clubs. I wish I had that guitar back!

In a town where you can get ridden out on a rail for not playing Telecasters, what made you pivot toward the Gibsons and Paul Reed Smiths you favor now?

It started with Dann Huff, who took me aside after a show and said, “You’re a wonderful player, but you don’t have a personality yet.” I said, “What’s your idea?”

We were cutting “Life Is a Highway” for the Cars soundtrack. That was the first song I ever cut with Dann, and he got out one of his old Les Pauls and told me, “Plug this guitar into that amp and just feel it.” He also had a Keeley compressor pedal and a Fulltone overdrive chained into his 4x12 Bogner cabinet and head set on channel three, which is the rhythm channel with a little more dirt. We cranked it up. It was really hot. I was sold.

You alternate between playing with a pick and your fingers. How did you develop that approach?

Brett Mason, again. I was using glue-on nails at one point, because that’s what Brett was doing. He seemed like a stud, so I figured that if he could get away with it, I could too. You get a nice linear sound. Brett would use his index finger to pop the strings, to get a different tone. I switched to a flat pick and three fingers, and popping with that middle finger. That combination gives you a variety of tones within your guitar’s tone.

Jeff Beck’s been an inspiration, too. He’s also one of Dann’s heroes. Jeff’s technique…the way he rolls the volume and plays at the same time. He’s like a pedal steel player who is missing some levers. There were a lot of guitarists in the Sixties and Seventies, including Jeff, who built their fingerstyle picking up. I wonder if Chet Atkins was so dominant back then that some of the best country and rock guitarists tried to emulate him. He is the greatest guitarist there ever was. He would play the bass part, play the interior part of the chords and the melody all at once. Amazing.

What’s most important when you’re building a solo?

When I’m recording a solo, I like to play to the tone, so I dial up a new sound and then see if it fits in the box. I try to avoid going back to the same tones I’ve used before. I really want to be inspired. If something doesn’t work, I’ll get another guitar, another amp, change the setting. And I don’t wig out when I make a mistake. Mistakes are sometimes where the real emotional stuff occurs. With Pro Tools and the other electronic gear we have, it’s easy to go in and make things tick-tock perfect, but sometimes a bend that isn’t quite right fits the emotions in a song best.

You’re obviously a key figure in modern country guitar. Was there a point when you felt you’d arrived at your very own style?

I don’t know if I’ve had that feeling yet, to be honest. Recording “What Hurts the Most” [for Rascal Flatts’ Me and My Gang album] in 2005 was a very personal experience. There’s a simple blues solo that comes in and goes out really quick, but when I slid into it I felt a kind of attitude and happiness with what I was doing that seemed really natural and right. Just before the “record” button got pushed, Dann told me to do anything I wanted, even if I might make a mistake. I’ve always been a fan of sliding into solos, and when I did, it seemed to come pouring out.

I moved to Nashville because I wanted to play country like what Vince Gill was doing—in a way that’s a tip of the hat to the purists but also brings your own qualities as a musician to the game. Playing guitar was a safe haven to let loose of my emotions as a teenager. Maybe the only difference now is I’m an adult.

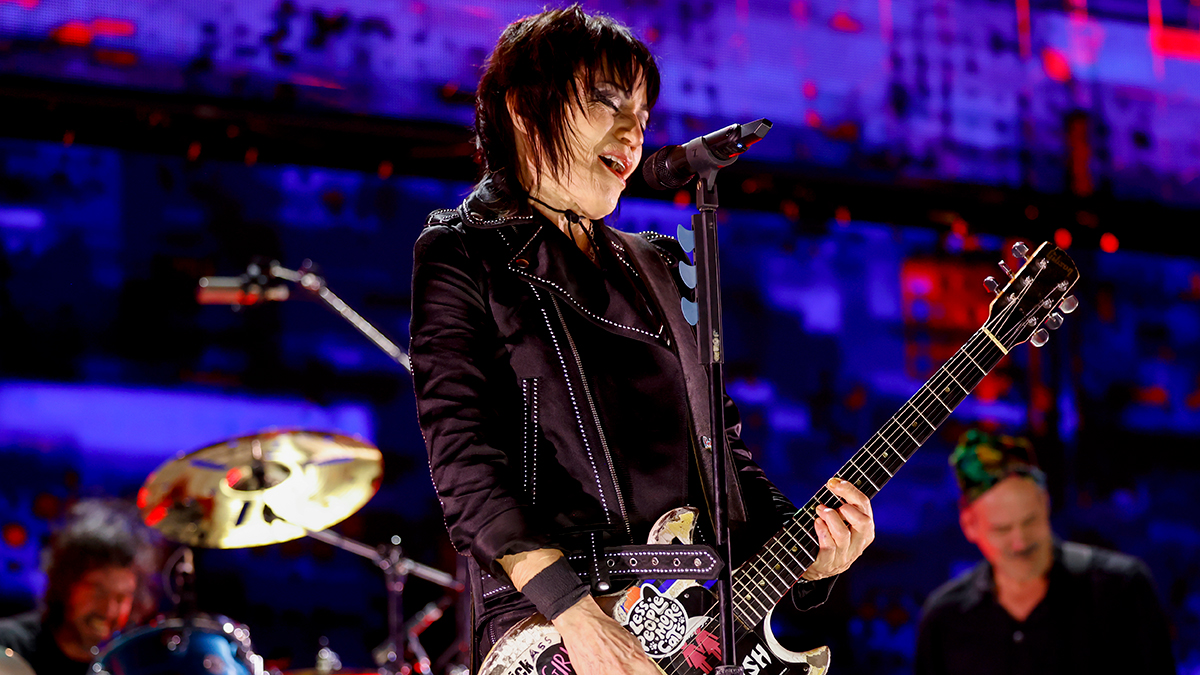

Photo: Russ Harrington