Joe Satriani Opens Up in His First Guitar World Interview from 1987

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Here's our interview with Joe Satriani from the December 1987 issue of Guitar World, which featured Joe Perry on the cover. The original story by Gene Santoro started on page 42 and appeared with the headline, "Wailin' With The Alien."

To see that cover—and all the GW covers from 1987—click here.

Things have certainly been changing for Joe Satriani. Suddenly a lot of people besbooides a few musicians know his name, have heard about his awesome chops, are picking up his first record, Not of this Earth.

Which must be why, on this hot and muggy Sunday night in New York hundreds of folks have thronged to a converted church, now a club, called Limelight. In conjunction with the New Music Seminar, Guitar World is sponsoring a concert featuring Satriani.

He finally appears onstage, with bassist Stuart Hamm and drummer Jonathan Mover around 1 a.m. to anticipatory roars, and proceeds to carom his fat, freaky sounds from the choir loft to the vaulted wooden ceiling.

He doesn’t do any leaps or splits, through he moves around; mostly he’s busy peeling off licks from a bulging book, digging in for the right riff, the cutting tone, the squealing harmonic pinched to stab at the right moment, a wang-bar doodle or some finger vibrato twisting the knife, a two handed tap to finish you off. In a word—taste.

Guess that’s one of the things Steve Vai and all those other cats who used to drop by his Westbury, Long Island, house a few years back learned from him.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

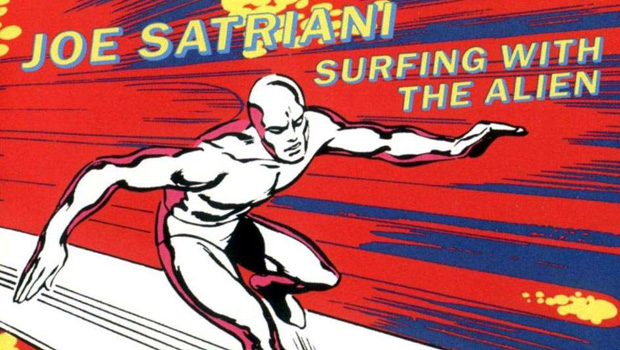

By the time you read this, more evidence of Satriani’s tastiness will have hit the record racks. Surfing With The Alien is still in rough mixes at this writing, but its power and range, from meditative acoustic work to metalloid romps, are clear enough. So Joe and I sit in his midtown Manhattan hotel room surrounded by guitar cases and a few crated rack effects, breathing deeply in the air-conditioning, inhaling espresso and Perrier and talking.

He’s a soft-spoken guy, though he obviously knows exactly what he wants and how to wait, if necessary, to get it. After hearing—who else?—Jimi Hendrix, the 14-year-old Satriani abandoned his drums for a Hagstrom III his guitar-playing sister bought him.

He taught himself some basics by playing along with his older siblings' records, a variety of discs that included the Stones, the Beatles, Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, Led Zeppelin, Johnny Winter and Mike Bloomfield as well as Motown hitmakers, early r&b and even some jazz stuff belonging to his parents.

Guitar lessons ended after a couple of shots: "The guy was teaching me 'Jingle Bells' and I had already memorized the chord charts from the back of an Alfred Guitar Book my sister had."

A more fruitful path opened up when he studied theory at Carle Place High School with Bill Wescott, whom he credits as "my main musical influence. Besides teaching me theory and all the technical things like writing and sightreading, he personally demonstrated what it was like to be passionate about music. It made me feel like I wasn't such an oddball if I got emotionally involved in what I was doing." It was via that school that Vai and others discovered Satriani.

After passing on Berklee for a brief dip into the Five Towns College music program, Satriani studied for two months with jazz piano great Lennie Tristano, whose hardnosed training shaped many fine players.

Like other Tristano alumni, he has some tales to tell: "It was really intense. In terms of' discipline, and self-evaluation, and changing my entire picking style, it was really a dramatic experience. I've never been that strict with any of my students. If I made a mistake during any of the parts of the lessons that weren't improvising, he would just get up, walk over to his desk, take out the book, and say [mimics Tris tano's rasp], 'Okay, Joey, I guess I'll see you next week.'

I had a couple of 60-second lessons where I'd just play the wrong scale 'cause I'd be so nervous. The flip side to the coin was that when you did all right, you'd be in there for two hours and he'd have 15 people standing in the hallway waiting for their lessons.

"He taught me what learning my instrument was about. Before then, I'd learned how to play by jamming, so everything I did was simply by feel: although I knew scales and modes, I didn't know them everywhere, only where I had played them. He would have you do these enormous lessons, like learn the harmonic and melodic minor scales in every key for every possible fingering starting off of every string and every fret. And that would just be point one of a seven-point lesson. If you fucked up and said 'I should' or 'would' or 'could,' he'd blow up and give you a lecture about living in the subjunctive mode. But he was a beautiful, crazy guy."

While he was working with Tristano, Satriani was gigging around Long Island with a several-piece dance band called Justice; then they hit the road, touring cross-country for about a year. A brief stop in California found him woodshedding for 15 hours a day and deciding to continue his musical career; a six-month sojourn in Japan was followed by his settling down in Berkeley, CA, where he set up shop as a guitar teacher and formed a power-pop trio called the Squares in 1980.

After five years of club dates and opening-act slots, Satriani decided to split the Squares for his own career. The result was his first LP,

Not Of This Earth

. It was not exactly an overnight success story, as Satriani tells it:

"It was in the can for about a year-and-a-half, basically It was done in the first four months of 1985, mastered and ready to go in June. Then while the contract was being mulled over, I got the offer to join Greg Kihn. On a musical level, that was great; they're a great American rock 'n' roll band. I'd known Steve Wright, the bass player, for many years, and they had asked me to join the band two years earlier, but I turned them down because I thought the Squares were going somewhere.

"Of course, right after that Greg Kihn became extremely popular, had two Number 1 hits [laughs ]. This time, it came at a better time. I wasn't doing anything, I didn't know if anyone was going to pick up my record, and I was heavily in debt, because I had recorded the record on a credit card. A company in Virginia had sent me one in the mail, somehow knowing that Joe Satriani wanted to do a record and needed it [laughs].

"So the tour helped me out of debt and as well provided a whole new experience of playing live. This was a different league, and he paced a show differently. Plus the combination of Steve Wright on bass and Tyler on drums was great; Pat Mosca and I were free to roam all around musically.

"During the time I was out on the road with him there were petty hassles and delays with the record so that it took 11 months before it was released. But in retrospect, it was perfect timing. The company's been promoting it well, people have been responding to it, and so for a record that I thought I was gonna press a few hundred copies of and then go my merry way, it turned out all right."

A brief tour on his own boosted Satriani's morale and got him into the idea of taking his music on the road.

"After I left Greg I played with Danny Gottlieb and Jonas Hellborg and a Swedish singer named Anika who actually did vocals to things like 'Hordes Of Locusts.' It was a short Scandinavian tour-three weeks. I flew over to Sweden a week after I'd been in a car accident—I was under medication, not in good shape. We had three days to rehearse, and we rehearsed maybe an hour [laughs]. Then we went out and did these gigs, and they were really good. It was all because Jonas and Danny are live players: They have a great vocabulary, they're smart, and they're crazy [laughs].

"I think you've gotta be smart enough to be competent, but you've gotta be crazy enough to go out there and just let it all happen. I mean, you can rehearse and still not be musical, be tight and not be musical; we all hated that."

Though he'd already begun writing for a second LP while on the road with Kihn, now Satriani got serious. His methods: "It's never changed from the beginning, just sort of chaotic and organized at the same time, comes in lots of different directions. I've actually sat down, taken out a guitar, and said, 'I'm gonna write a song that makes me feel like driving at night' or whatever. When the feeling is upon you, so to speak, you act.

Then there are other songs that took a very long time, like 'New Day,' which took so long because I didn't know what it was that I wanted to write. I knew that I wanted to write something that was completely different, so I tried all kinds of things: I would meditate, stare at the tv, go out and see strange movies, run a couple of miles, read strange books, drink lots of coffee, not drink any coffee-whatever would set me off.

"So for three or four hours, day after day, I tried to write, come up with something different. Slowly, I came up with the idea that what I was hearing in my head was a series of fourths, fifths, thirds and seconds, and I realized suddenly I was playing a song that was a melody and a rhythm, and it was built off the idea that there were always two strings being hit.

Then I had to teach myself how to play it. It doesn't sound difficult, but physically it was perplexing. So I had to struggle to learn how to play it so I could write it before the idea left my head. As soon as I was done, it was just like I'd learned to ride a bicycle for the first time—I couldn’t get rid of it [laughs].

"Then other things like The Enigmatic was a scale that I loved, and so I took out a piece of paper and gave myself a lesson wrote but all the triads and all that, this is what it is, now be creative with it. I wanted something really strange, y'know, like fast cuts in weird movies.

So, much to my drummer's surprise, I told him I didn't want the kick drum on the upbeats; as a result, a lot of people feel that the one is in the wrong place in that song, because the kick drum is continually and-and-and. I wanted it to be like someone pushing you on the back—and those people never push you at the right moment, know what I mean [laughs]?

"It's always when you're off balance. So the snare is always on two and four, and the hi-hats and shakers are going tsk-tsk-tsk very evenly, and there's that kick drum-just enough to make you snap your spine [laughs ]. Kinda like the Miami Vice chase scene music. We had a good time doing that.

"Most of the time I write songs with the arrangements all at once, in my head. There's the producer side of me that's always thinking sounds, like 'wouldn't this be a great sound if it existed to put in front of a song, to open it up, and then when it did its thing something else would happen?"

"Then I'll fool around and get a noise that's like that, then say, 'Okay, how am I gonna write a song where I can put this to use somehow.' Sometimes I've done it that way, other times I'll have a beautiful melody or a rhythm pattern and go over it and over it trying to figure out how to present it. 'Not Of This Earth' is a good example, of that: it started as three chords, and I was so intrigued by how new it sounded when it got back to the first chord again that I thought, 'How can I pull this off so people aren't saying, 'Oh God, those same three chords over and over again.'

"So I thought, 'What if I could get the bass guitar to play only one note" I eventually had to add one other, just for a release, but I tried to make it as simple as possible. Then I thought, 'I want really strange drums, really big, but I wanted them to change.' So we used the nonlinear reverb, and [drummer ] Jeff Campitelli just hit the snare as irregularly as he could, sometimes a solid hit, sometimes a rim shot, and that opened up the linear sound in different ways.

"Then I decided, after playing over it, that what I needed were two melodies that could be good enough on their own, and could then eventually be played together. That was a bit of a trick; to my mind, that song was like a sleight-of-hand, like something by Eric Satie, playing with you by using as few notes as possible and getting you to realize that it really is a song.

"Whereas something like 'Hordes Of Locusts' is a huge arrangement, more like Beethoven, where everything is exaggerated, lots of different melodies. The middle section after the main melody-not the sitar part, where it starts with the D chord-I had written this heavy part, because I thought everybody's gonna be expecting your average heavy thing, but listen to this [laughs].

"So I threw in a chord and a bass line that to most people would sound like it made no sense at all, but to me it was a release to hear it at the time. In my mind the chord sequence is like a long melody and it takes until you get back to that C#. I'd have to say that sequence was part Chopin, like his use of the minor sixth chord with the raised eleventh, and part John McLaughlin, around the time of Inner Mounting Flame, where he'd use chords like the C major seventh with the seventh in the bass, "C/B," as some people call it.

"So I thought, 'I'm gonna take Chopin and McLaughlin and put 'em to this heavy song where I've got scratches and sitars and I'm gonna try to make it work.' That's the part of me that's producing that says this is gonna sound good to you, that wants to make it a sound event as well as a piece of music."

Nor does he view his music as just a frame surrounding his guitar excursions: "There are a couple of different types of solos I play. There are some that I personally can't rehearse; they don't have any meaning or function in the song other than to be totally improvised. So 'Ice Nine' [on Surfing] has two solos that are just completely off-the-cuff, because they come at a point where there's guitar everywhere in the song.

"So when the solos hit, the last thing you want to hear is organized tones [laughs]. So I do my best to create these two different guitar players, one cuts the other one off right toward the end of the solo and does something else; what finishes it up is a backwards thing that's really wild. Similar is 'The Enigmatic,' where the solo is even more chaotic than the song, which is pretty chaotic [laughs ].

"So I used techniques that have nothing to do with normal playing- scraping the strings, using metallic objects on them, tapping them weirdly—and built a pattern as I went along. So that way it's like improvising. Lennie Tristano used to say; 'Never be judgmental about your improvising,' and so I try to remember that, try to be free and let it go. I've had the experience of going into the studio, being totally prepared, playing the first three notes and saying, 'I'm bored, I've heard this already so I'm not excited about playing it.'

"So even the solos that I'd prepared for the album, that I thought were necessary for the song as a melodic pattern, I might start that way but then change around once I start playing. Like the first few notes in 'Rubina' or 'Hordes Of Locusts' came right out of my head, I just can't seem to hear anything different; but what follows doesn't matter, it's just something I fill up."

Now that he's finished with the studio, he’s hungry to take his new trio on the road. "We've only played together twice, one show in Chicago [at the NAMM show] and here in New York. We didn't rehearse or anything. The chemistry is really good. We have a good time simply going off. Generally I'll tell them, 'You can do whatever you want, use your vocabulary, just don't screw the song up. And when we get to the end of the song, let's go somewhere.'

"The rule is, Whoever plays first, wins [laughs]. If you wait to set; where the other person is going, and you're worrying about what he's gonna do, you might as well go first, and then everybody has to follow you [laughs ]. 'Cause with the people that I play with, I like to hear them continually pour out whatever they know.

"It's an instrumental trio, but I don't want it to be a jazz thing; it's a rock instrumental gig, really At the same time, we're players who have played a lot of music, we like a lot of music, and when we play we like to throw in lots of things. Live, it explodes."