Talking Gear and 'Juice' with John Scofield

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

He’s played with jazz legends from the past and jam heroes of today; he’s burrowed into the roots of bebop and blazed new territory in the world of funk; he’s a fearless soloist as well as a cool cat to have on your team.

His name is John Scofield — and for all he’s accomplished in his career, he’s simply a nice guy to talk music with.

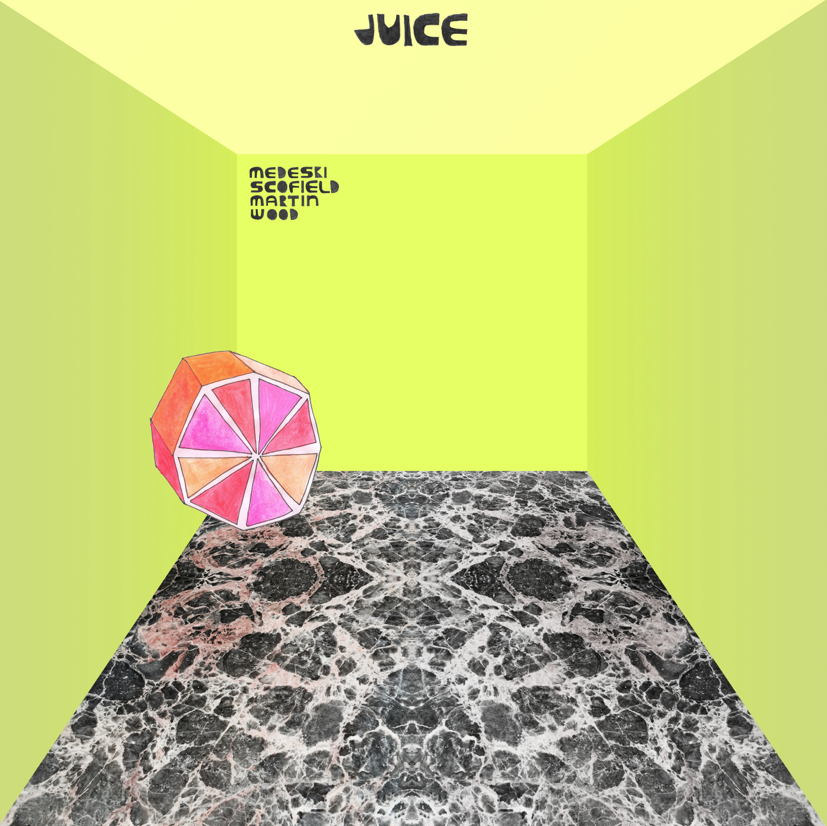

Scofield’s latest project is a reunion with buddies John Medeski, Billy Martin and Chris Wood, the avant-garde jazzbos he first worked with on 1998’s A Go Go. Their 10-track studio release, Juice, is a mix of originals and covers, infused with the unique global funk jams the MSMW collaborative have come to be known for.

Here are some thoughts from Scofield on gear, going out and — most importantly — how to get back.

GUITAR WORLD: Well, John, 30-plus years down the road and you’re still coaxing new sounds out of that ’81 Ibanez AS-200. I’d almost say that one’s a keeper.

Yeah! [laughs] Hey, I feel like a traitor to my country because I’m supporting a foreign-made guitar … but what the hell? [laughter] It’s a beautiful guitar, man. I like semi-acoustics. I had a Gibson 335 before that, which I still have. I just really dug that Ibanez when it was given to me in 1981.

Who gave it to you?

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

Ibanez. I was on tour in Japan and at that point, both Ibanez and Yamaha were being really aggressive about getting all the American artists they could get to play their instruments. I had my 335 with me, and it had really gone through some changes; it was playing really weirdly. Back then, I didn't know how to do neck adjustments … I wouldn't trust myself to do it, you know?

That’s when Ibanez brought me this brand-new AS-200 to try, and I said, “Man, this plays great and feels great … it feels a lot like my 335.” I began playing it on that tour. When I got home, I had the Gibson adjusted, but I’d been playing the Ibanez for a month and was used to it … and I’ve been playing it ever since.

Sometimes I’ll play the Gibson, which I really like, too. They're just different animals; there’s something about that Ibanez that I’ve just grown accustomed to. I can really get something out of it, you know?

Have you experimented with pickups over the years, or is she still pretty much stock?

I actually have two Ibanez AS-200s, two old ones. I changed the pickups on one of them and put some Voodoo Humbuckers on. But the main one I play still has the original pickups, which are, like, the loudest pickups known to man.

Is there a warning label on them?

There should be! [laughs] I’ve never played a louder pickup … it’ll blow up amps, you know? [laughter]

Speaking of amps, what was your go-to for the Juice sessions?

I used one amp for the whole record: my Vox AC-30. It’s a reissue from the late Nineties that I modded out a little bit. I changed one of the speakers so they’re mismatched, which is what Matchless does. I have a Matchless amp I really like, too.

What did you put in for the second speaker?

Another Celestion, but a different wattage. One’s a 30-watt and the other’s a 15. It’s exactly the same setup as the two speakers in the Matchless 2x12 combo.

You usually have a pretty impressive array of pedals by your toes, but even when you tap into them, you really have a light touch. I mean, every now and then you go a little bit apeshit — in the nicest of ways.

[laughs] Thanks!

But you don't rely on a lot of effects, which is something I appreciate.

You know, I started off just playing … and that’s still the main thing I do. It’s really nice to have — especially in the jazz/funk area like on Juice — some of the effects to get different things happening.

It’s kind of like, if you’re going to play an hour of music, after a while you’re looking for something else besides the regular guitar tones. It’s fun now and then … but yeah: the main stuff I do is my guitar.

When the four of you get together, are there any ground rules as to who’s going to play traffic cop?

You know, there are certain tunes that definitely have arrangements … and then there songs that have an arrangement, but we’ll start with some free stuff.

Sometimes we’ll say, “Let's start completely free and just see where it goes — and then we’ll start segueing into this tune.” It's not like we're totally playing “anything goes” in that we have a game plan. It seems to help that we have both structure and no structure — it helps to keep it from being boring.

Even in the free stuff, I notice that John, Billy and Chris are all really good at shifting gears quickly. Right when you think, “This needs to go somewhere else,” they’ll dramatically go there as a group. They have an ESP-type ability, which is pretty cool.

What are some key elements of your playing that you think have changed over the years?

Oh, man … [laughs] You know, when I listen to stuff I recorded when I first started playing, it’s things like … like the way you get out of a phrase that I didn’t know how to do. I didn't know how to get the note to stop ringing; how you let the last note you hit fade out; how you come off of it.

To take a breath — like a horn player.

Exactly. You need to let the space happen … and when you come back in, you need to get back in the groove and really be part of the rhythm section. Put yourself into the rhythm section, you know? Don't play over it — put yourself in there.

A former offshore lobsterman, Brian Robbins had to wait a good four decades or so to write about the stuff he wanted to when he was 15. Today he’s a freelance scribe, cartoonist, photographer and musician. His home on the worldwide inner tube is at brian-robbins.com (And there’s that Facebook thing too.)