“I might have done better in the Bluesbreakers than in the Yardbirds, but I certainly wouldn't have had the same kind of free rein to experiment”: Jeff Beck on his relationship with Eric Clapton, jamming with Hendrix, and turning down John Mayall

In a 2010 chat with GW, the always creatively restless virtuoso discusses his love of John McLaughlin, what he sought out to do when venturing into the world of classical music, and the musical icon he wished he had had the chance to collaborate with

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The following is a fan-submitted Q&A with Jeff Beck that was first published in Guitar World in 2010.

He is held in the highest regard by Eric Clapton and Jimmy Page, was close friends with Jimi Hendrix, and his mid-Sixties recordings with the Yardbirds invented the sound for heavy metal guitar. But what Guitar World readers really want to know is...

On your new album, Emotion & Commotion, how did the idea evolve to record with a 64-piece orchestra? – Albert Shorofsky

“I was listening to an interview that I did way back in 1966 with Brian Matthews, the guy that ran the Saturday Club radio show in England, and there was a clip where he asked me, ‘What would you like to see yourself doing in the future?’ and I said, ‘I’d like to play with a big orchestra.’ [laughs] I couldn’t believe that – even way back then, I was thinking about doing that.

“At the time, I’d seen Tina Turner and heard the amazing sounds of the Phil Spector productions that featured big, powerful string sections, and the orchestral sounds on other pop records, too. I thought, ‘There couldn’t be a better backdrop for some kind of powerful music than a big orchestra.’ My wish to hear how a guitar would sound in front of an orchestra has always been there.

“Recently, I did a version of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony for an album that I hope to be accepted by EMI Classics. They said they loved it and wanted 12 more pieces, but it took so long to learn the Fifth and get it right, I imagined it would take another six months to get the rest together. So I took the idea and, in order to make it a little easier on myself, I chose somewhat simpler melodies that could be rattled off fairly quickly just to see if it worked, and everyone seemed to like the results.

“For the new album, I originally wanted to present two CDs in the box, with Emotion, the orchestral stuff, on one disc, and Commotion, the stuff with the band, on the other. I went into the studio one day and [producer] Steve Lipson had sequenced the orchestral and band tracks together. He said, ‘What do you reckon?’ and I said, ‘It sounds all right to me. Let’s carry on!’

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Every time I walked into the studio, I wouldn’t remember what I’d done the previous day, and there was no kind of rhyme or reason to what was going on until he started to sequence some of the demos together. We forced it together. The ingredients were pleasing musical pieces but there was no preconception to it, and it just happened.”

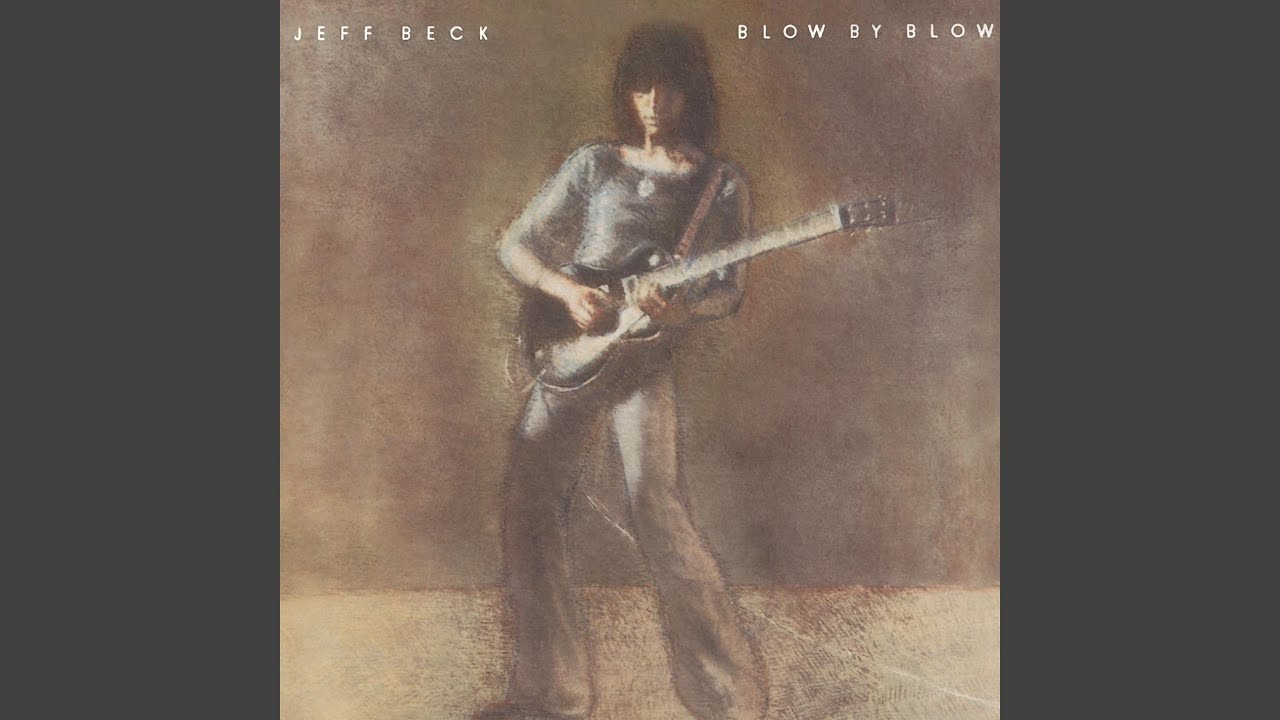

The orchestral works on the new album sound fantastic and are reminiscent of the track Diamond Dust, from Blow by Blow. Would you say there is a connection between Emotion & Commotion and Blow by Blow? – Leroy Ray

“This new album is not dissimilar from Blow by Blow in terms of the approach, where it was done in a ‘seat of the pants’ kind of way. When nothing’s planned, that’s when the results seem to happen. I don’t organize myself sufficiently to get an album of material together, book the studio, and go. I need to be kicked; I need to be forced physically to go in. That’s how it works for me. I’ll get a great idea in the house, and it’ll stay there unless somebody comes and drags it out of me!”

I was trying to make the guitar do things it’s not supposed to do

One of the most ambitious tracks on Emotion & Commotion is your presentation of Nessun dorma, from Puccini’s opera, Turandot. Also, you share the melody of Elegy for Dunkirk with opera singer Olivia Safe. Are you a classical music fan? – Bruno Curreri

“Around the time I did my recording of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, I was looking for some other pieces to record. One that I liked very much was Ravel’s Pavane, so I learned that, and I was listening to what they were playing on the Albert Hall Prom [the Henry Wood Promenade Concerts].

“Every year they have a prom, which is a big music festival. I’m looking away from rock and roll into proper, serious melodies, and, for me, it has been a good playground to look into. And Pavarotti never ceases to amaze me; the bellowing – the big, deep, proper opera singing – is something I love, and I was keen to try Nessun dorma, which he sang magnificently. My guitar is not a voice, and it’s not his voice; I played it like a spirited, bluesy thing. That’s what I was trying to do: make the guitar do things it’s not supposed to do.”

Your latest DVD, Performing this Week… Live at Ronnie Scott’s, features a set list that spans your entire career. Does each of those songs have a special meaning for you? – Irene Coco

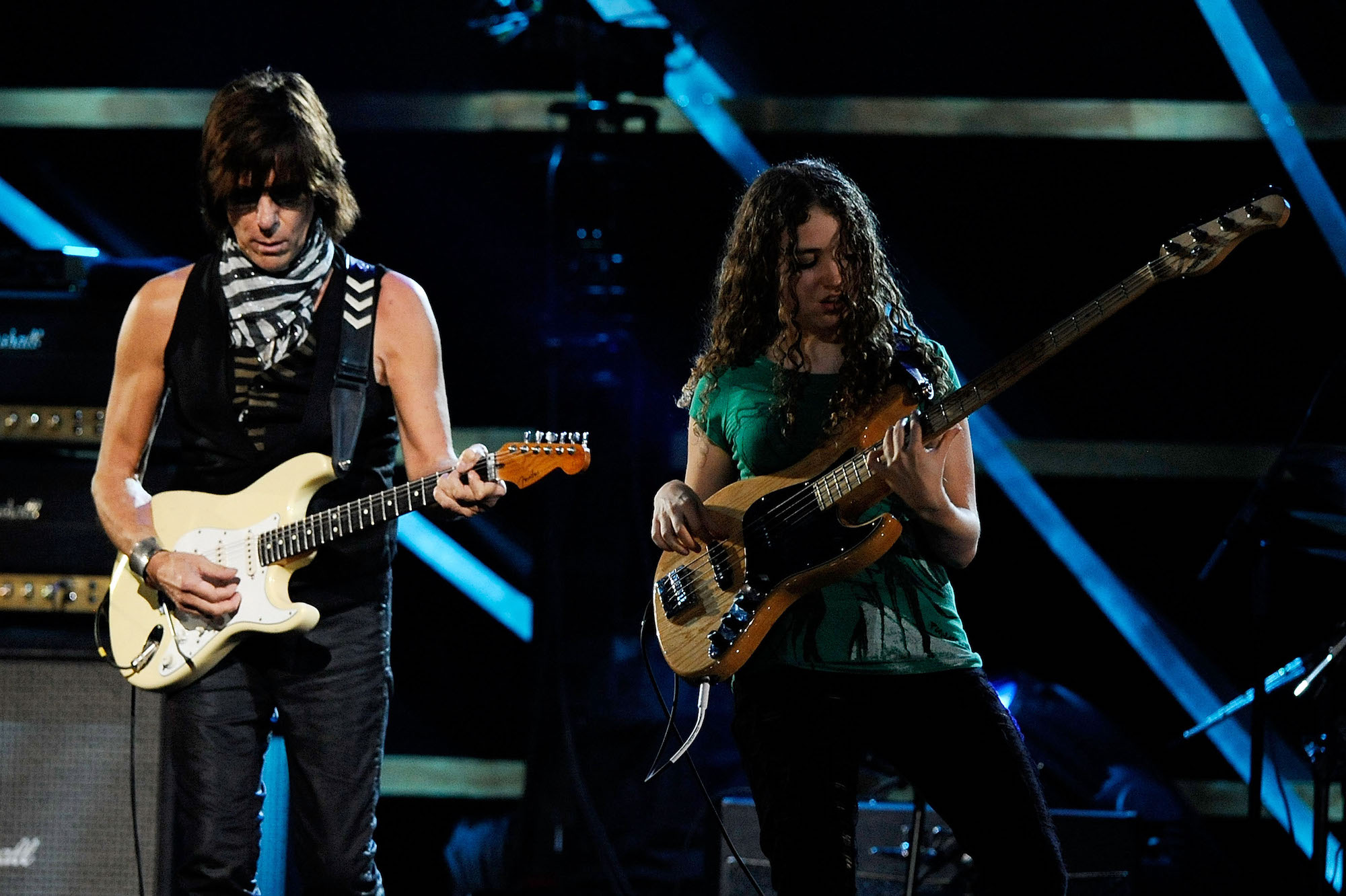

“When I first went out with the band with Tal [Wilkenfeld] and Vinnie [Colaiuta], we were short of new material to play, so I thought, ‘Why not do a quick trip back through time, and put some of the early stuff in there?’ Albeit without Rod [Stewart].

“We did People Get Ready and stuff like that. I think it added up to quite a good journey back through history, so anyone that hadn’t seen me got a snapshot of what was going on back in ’66 and ’68. As opposed to bombarding people with brand-new, avant-garde techno, I thought it would be better to establish a foundation for people to hear, and it seemed to work.

“Two of the songs at the start of the set, [John McLaughlin’s] Eternity’s Breath [from 1975’s Visions of the Emerald Beyond] and [Billy Cobham’s] Stratus [from 1973’s Spectrum], I played because I want people to realize that music was around, plus it’s still fun to play.

“I’m just a messenger for John on those songs, because I want people to listen to him. If people enjoy my version of it, then my job is done. John is so far ahead of his time – he really is. He’s not half as well known as I’d like him to be. Those songs are played with the most heartfelt respect. Nowadays, to really sort out the men from the boys, John plays mostly acoustic, which cannot be bluffed.

“Billy Cobham’s Spectrum album gave life to me at the time, on top of the Mahavishnu records featuring [keyboardist] Jan Hammer. It represented a whole area that was as exciting to me as when I first heard Hound Dog by Elvis Presley. They were inspirational to me to the point that I started to adopt that type of music.

“Tommy Bolin’s guitar playing on Spectrum is fantastic. What a sad loss; he was on the tour when I was out with Jan in 1976, and Tommy died after the first night of the tour in Miami. I heard the news the next morning.”

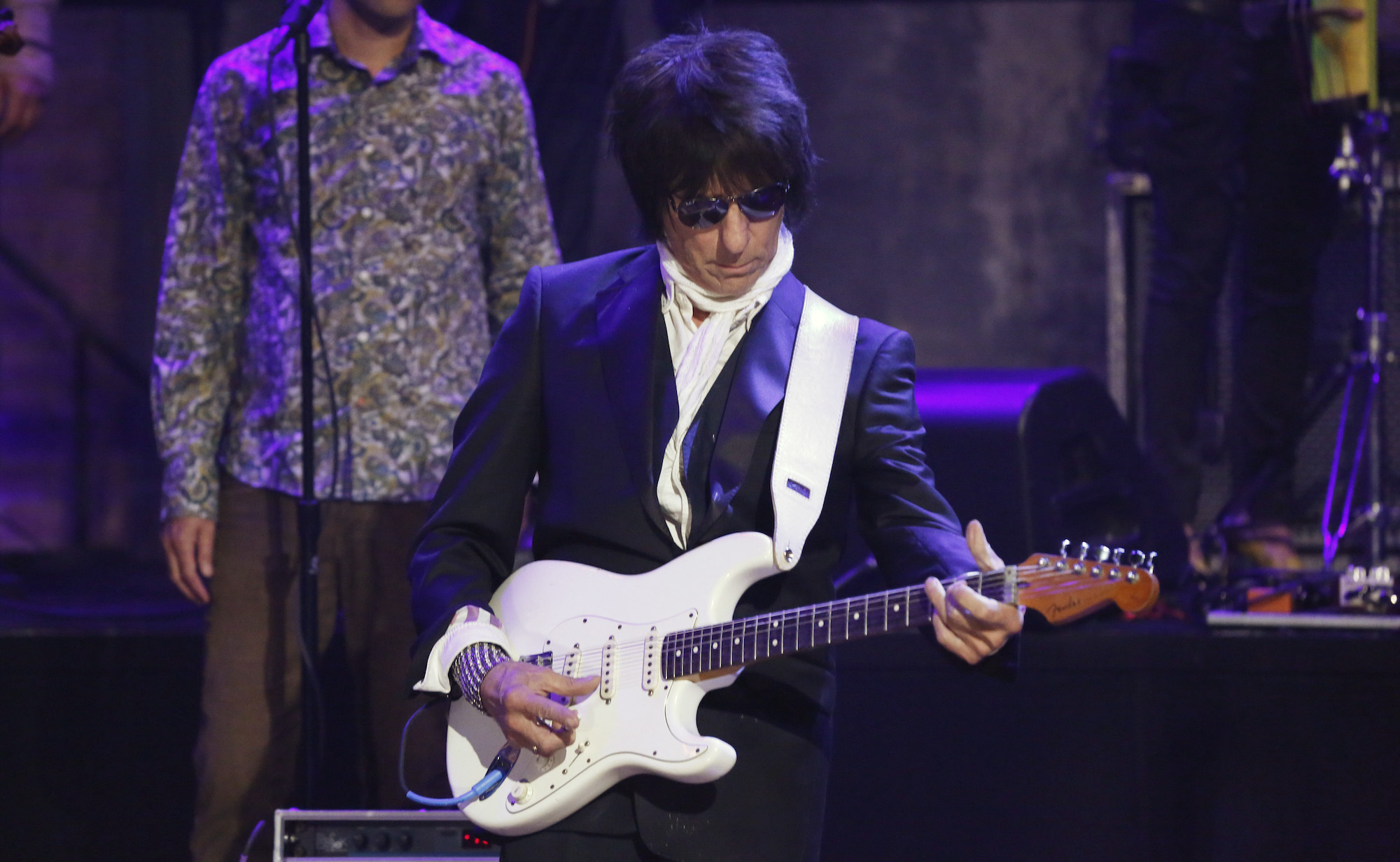

You are currently on tour with fellow British guitar great Eric Clapton. As the guy that replaced Eric in the Yardbirds, was there ever any animosity or competitiveness between the two of you? – Hilary Franceschi

“Playing on this tour with Eric has been a very happy turn of events. First of all, I think he actually likes me after all these years, which is heart-warming. I didn’t realize he detested me quite so badly until he revealed that recently in Rolling Stone. [laughs] He said we were enemies, but that was more on his side.

“I was subservient to him when I joined the Yardbirds, because he was such a big ‘face’ there. But when I developed my own wacky style with the Yardbirds albums, I didn’t feel in any way that I was encroaching on his patch at all, nor have I ever since then, along with when [producer] George Martin came along for Blow by Blow and Wired.

“George gave me the confidence to play on an instrumental album, and at that point I was absolutely cleared from any kind of ‘direct’ challenge to what Eric was doing, or anyone else for that matter, in terms of clashing styles. And yet, I think Eric wanted to be the guy associated with the guitar, which he subsequently became. You stop anybody on any street, around the world, and they know who Eric Clapton is. They don’t know who I am! But we’re going to change that, aren’t we? [laughs]”

You’ve always played with a wonderful type of aggression, throwing wild sounds at the audience in a way that says, ‘Deal with this!’ Where does that attitude come from? – Angelo Barth

“It’s like a tantrum. Those things are outbursts, like exactly what I wanted to do to the teachers at school. It’s a bottled-up frustration that manifests itself in those outbursts, as well as a reflection of my life and my reaction to the difficulties of it. Singers are like that when they start screaming, like Screaming Jay Hawkins [Beck covers Hawkins’ I Put a Spell on You on Emotion & Commotion]: One minute he’s singing perfectly normally, and then all of a sudden he bursts into rage. Love it.

“I like an element of chaos in music. That feeling is the best thing ever, as long as you don’t have too much of it. It’s got to be in balance. I just saw Cirque du Soleil, and it struck me as complete organized chaos. And then there was this simple movement in the middle of the show, which was a comedy, and I thought, ‘What a great parallel between the way that I think and the way this circus is happening.’ It had a special meaning for me, aside from the spectacle of it all.

“When I came away from it, I thought, ‘If I could turn that into music,’ it’s not far away from what my ultimate goal would be, which is to delight people with chaos and beauty at the same time.”

Can you describe the feeling of sparring with Eric Clapton on a nightly basis? –Sherwood Meara

“Playing these shows with Eric was like going back into the school playground, but this time I was the hero instead of being beaten up every night! It was a great feeling, like going back to visit a bunch of old friends, with the license to play as you wish as opposed to a ‘traditional’ way, along with the guy that is the boss. Eric is definitely the boss.”

My only connection to Eric was hearing the rest of the Yardbirds talking about him, that he used to do this, that and the other. I got pretty pissed off with it, like, ‘Shut up, I’m here now!’

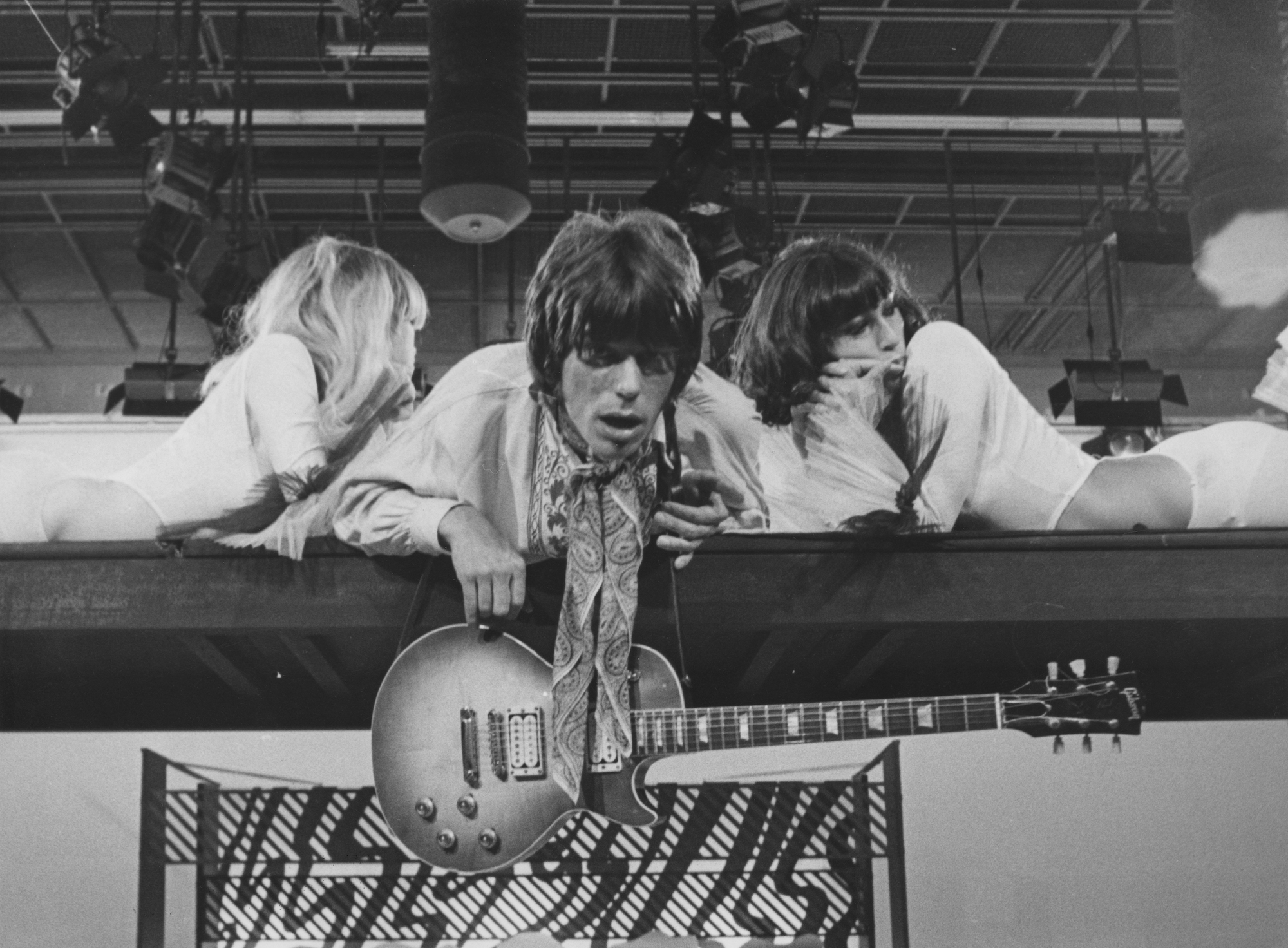

There were so many incredible guitar players in England in the mid Sixties – you, Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, Mick Taylor, Peter Green... Were each of you very aware of one another’s careers, and did you play together often? – Hugh Finsecker

“Mentally, there was some subliminal connection between all of us, wondering what one another were doing, but physically, no, we were not around each other very often at all. Eric lived not very far away from me at the time, and Jimmy lived not very far away, either, but I hardly ever saw Jimmy until I got him into the Yardbirds as the bass player. England being so small, many people think we all lived in Buckingham Palace together [laughs], but in fact we saw each other very rarely.

“I joined the Yardbirds in February of ’65, and I’d never seen sight or sound of Eric with them before that. My only connection to him was hearing the rest of the band talking about him, that he used to do this, that and the other. I got pretty pissed off with it, like, ‘Shut up, I’m here now!’ For the first couple of weeks, all I heard was, ‘Oh, Eric, the girls love him in this place,’ and I’d say, ‘All right, enough of that!’

“I didn’t see him until about a year later, because we were off to America. Right when I joined the Yardbirds, they had a massive hit with For Your Love, which Eric detested and was the reason he left the band. So we were off pummeling around the States on the three-week promo tour.

“When we went back [to England], by pure chance I bumped into him in a club and I thought we were actually going to get into a fight! But when he saw me, he went, ‘Hello, man!’ and he gave me a big hug, and that was the end of that.”

Back in 1983, when you and Eric appeared together for the ARMS [Action into Research for Multiple Sclerosis] Benefit for Ronnie Lane, Eric was quoted as saying, “Jeff is probably the finest guitar player I’ve ever seen.” Was that actually the first time the two of you ever played together? – Paul Montgomery

“Wow, good Lord – did he really say that? I’m deeply honored. Before ARMS, we had only done the concerts with John Cleese and Monty Python [The Secret Policeman’s Ball, in 1979, and The Secret Policeman’s Other Ball, in 1981] so the ARMS concert was one of the first times Eric and I ever played together in front of an audience. We did a few things right after that, too, such as Amnesty International [in 1985].”

In the mid Sixties, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers were a band that served as a training ground for some of Britain’s best blues guitarists, such as Eric Clapton, Peter Green, and Mick Taylor. Did Mayall ever ask you to join the Bluesbreakers? – Alex Durant

“He did. John called my mum several times. He found my mum’s number, and she said to me, ‘Oh, that John Mayall sounds very nice!’ [laughs] But I didn’t want that – I didn’t want to be playing blues all of the time. I’d seen Eric with them, and he was fantastic, really.

“He did the job better than I could have, and I just didn’t want to have that challenge. My musical taste was changing radically from 12-bar blues. I might have done better in that band than in the Yardbirds, but I certainly would not have been given the same kind of free rein to do the experimenting that I did in the Yardbirds.

“John Mayall came to see me with the Yardbirds at some gig. He was very straightforward. He never embellished or gave us any flowery comments about the gig. He said, ‘The audience loved it, but there was not much blues, was there?’ And I thought, ‘Excuse me, but this isn’t a blues band.’ It sort of was, but he’s a purist and he was listening for Little Walter–style harmonica solos.

“I didn’t want to be mimicking Chicago blues musicians forever. My thinking was, ‘We’re not them, we’re not black, we’re British middle-class kids and let’s get on and do our own music.’ We had a bit of disharmony about that, but not to take away from John’s dedication to it.”

In the late Sixties in the States we were all very aware of a British blues explosion, but was there a sense in England that the music was really expanding, and that what came next – the musical adventurousness of Cream and Jimi Hendrix – was on the horizon? – Kate McCrae

“For me, the first shockwave was Jimi Hendrix. That was the major thing that shook everybody up over here. Even though we’d all established ourselves as fairly safe in the guitar field, he came along and reset all of the rules in one evening.

“Next thing you know, Eric was moving ahead with Cream, and it was kicking off in big chunks. But me, I was left with nothing. That was the hurtful part, because I didn’t have anything to come back at them with.

“Time went by, and I scraped by with Cozy [Powell, drummer for 1971’s Rough and Ready and 1972’s Jeff Beck Group albums], and luckily enough I got with BBA [Beck, Bogert and Appice, in 1973], which was a power trio. That helped, because they were so enthusiastic, and it was like Cream on acid! Then George Martin comes in and we start mellowing down a bit and making more ‘classy’ sort of music, I suppose you could say, with [1975’s] Blow by Blow.”

Jimi drove me up in his Corvette… that was the best moment. His driving was terrible

In the late Sixties and into the early Seventies, jazz legend Miles Davis was incorporating more of a rock approach. He was known to tell his guitarists, “Play like Hendrix.” Was there ever an offer of any kind for you to play or record with Miles? – Harry Booth

“In my mind’s eye, he was, and still is, so far up there in the world of jazz. He’s in a gold-plated place. Miles was one of those natural spirits that let the musicians do what they wanted to. On the Tribute to Jack Johnson album [1971, featuring guitarist John McLaughlin], you can hear John pushing a lot, and I think it was a great slight-of-hand on Miles’ part to get the vibe from someone else and then sit on top of that. There’s sort of a recirculating power going on.

“I would have loved to have had the chance to play with Miles, but it was never brought up. I don’t know if he even knew who I was. If he were to come back, I’d definitely knock on his door.”

I’ve read about Jimi Hendrix coming every night for a week to jam with the Jeff Beck Group at the Scene Club in New York City. Can you describe what that was like and your relationship with Jimi? – Charles Pizer

“We did six nights in a row there [in June 1968]. The initial gig that broke us in America was at the Fillmore East with the Grateful Dead. But after that success and the great write ups, we then had to go down-market at a small club for six nights. It gave everyone a chance to watch what they had just seen again, six times in a row. We didn’t really want to be scrutinized like that, in case we just happened to get lucky the night we played the Fillmore, which was quite good.

“The first night at the Scene, Jimi didn’t show up, but he came for the rest of the five nights. Around about the halfway mark, he’d come in from whatever recording he’d been doing. The buzz was incredible: the place was packed anyway, but when he came in they were standing on each other’s shoulders.

“Sometimes he didn’t have his guitar, so he would turn one of my spare guitars upside down and played that way, and I actually played bass at one point. I’ve got a photograph of that. Thank god someone took a picture, because there’s hardly any record of those goings-on.

“Around that time, Jimi and I played a secret gig, a benefit at [drug rehabilitation center] Daytop Village. Jimi drove me up in his Corvette… that was the best moment. His driving was terrible. We were stuck in traffic in the middle of New York City, and he had this brand-new 427 Corvette boiling over, and I thought, ‘I hope it doesn’t blow up right here!’ [laughs] I was thinking, ‘Why did you buy a Corvette in Manhattan?’

“I wasn’t looking for compliments, but before I met Jimi someone told me that he knew all about my recordings with the Yardbirds. He had to, because for someone so utterly flamboyant and played so inventively, I knew he was one for listening out. He wasn’t one of those staid, insular kinds of blues players; he would listen to everything. And that alone thrilled me.

“He’d also seen the Yardbirds live in 1965/1966 when he was playing sideman to Little Richard, I believe. It was amazing to see him play, and I’d met him before I saw him perform. I saw him at this tiny little club in London, with all of these ‘dolly birds,’ which is what they called girls dressed in their miniskirts. I think they all thought he was going to be a folky, Bob Dylan–type of character [laughs], and he blew the place apart with his version of Like a Rolling Stone.

“I just went, ‘Ah… this is so great!’ It overshadowed any feelings of inferiority or competitiveness. It was so amazing. To see someone doing what I wanted to do… I came out a little crestfallen, but on the positive side, here was this guy opening big doors for us. Instead of looking on the negative side and saying, ‘We’re finished,’ I was thinking, ‘No, we’ve just started!’

“I was delighted to have known him for the short time that I did. It was the magical watering hole of the Speakeasy, the club where we hung out in London, that enabled that to happen. It was the one place you could go and be guaranteed to see Eric or Jimi and have fun playing. Those places don’t seem to exist anymore.”

You’ve mentioned in past interviews that your guitar playing has been inspired by vocalists. Has your playing also been influenced by other instruments, such as the pedal-steel guitar, because of the use of the slide and the volume control? – Vincent McDowall

“Absolutely, yeah. I do a very poor man’s pedal steel on the Stratocaster. The people I listened to were [steel player] Speedy West with [guitarist] Jimmy Bryant. Unfortunately, the actual physical layout of the steel guitar makes it very difficult to recreate on a regular guitar. But it doesn’t stop one from listening to it and embracing some of the style. There’s a guy now, Bruce Kaphan, who is amazing.”

Your tribute to Les Paul at this year’s Grammy Awards was a show stopper, with your spot-on recreation of Les’ sound and style on How High the Moon with Imelda May. Can you talk about Les’ influence on you as a guitar player? – Dan Holland

“Les is sadly missed, but he had a great life and he gave us so much more than just the guitar. I’ve always been a huge fan, and his guitar playing inspired me a great deal. I was glad to have had the chance to get to know him. This spring, I’m going to be doing a tribute to Les with Imelda at the Iridium in New York City, and I’m really looking forward to it.”

Guitar World Associate Editor Andy Aledort is recognized worldwide for his vast contributions to guitar instruction, via his many best-selling instructional DVDs, transcription books and online lessons. Andy is a regular contributor to Guitar World and Truefire, and has toured with Dickey Betts of the Allman Brothers, as well as participating in several Jimi Hendrix Tribute Tours.