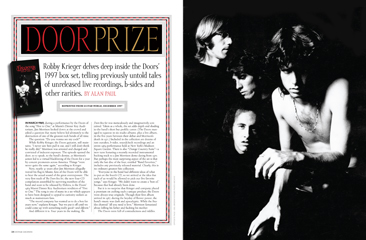

Robby Krieger delves deep inside the Doors’ 1997 box set, telling previously untold tales of unreleased live recordings, B-sides and other rarities.

In March 1969, during a performance by the Doors of the song “Five to One,” at Miami’s Dinner Key Auditorium, Jim Morrison looked down at the crowd and asked a question that many believe led ultimately to the destruction of one of the greatest rock bands of all time.

The question: “Do you wanna see my cock?”

While Robby Krieger, the Doors guitarist, still maintains, “I never saw him pull it out, and I still don’t think he really did,” Morrison was arrested and charged and convicted of indecent exposure. The episode opened the door, so to speak, to the band’s demise, as Morrison’s action led to a virtual blacklisting of the Doors for a year by concert promoters across America. Things “were never quite the same again,” according to Krieger.

Now, nearly 30 years after Jim Morrison allegedly waved his flag in Miami, fans of the Doors will be able to hear the actual sound of the great overexposure. The very first track of The Doors Box Set, the new four-CD compilation assembled by surviving members of the band and soon to be released by Elektra, is the Doors’ 1969 Miami Dinner Key Auditorium rendition of “Five to One.” The song is one of many in a set which appears to have been designed to appeal to curiosity seekers as much as mainstream fans.

“The record company has wanted us to do a box for years now,” explains Krieger, “but we put it off until we could come up with something really good—and different.”

And different it is. Four years in the making, The Doors Box Set was meticulously and imaginatively conceived. Taken as a whole, the set adds depth and shading to the band’s short but prolific career. (The Doors managed to squeeze in six studio albums, plus a live album, in the five years between their debut and Morrison’s death in 1971.) Included in the collection are dozens of rare outtakes, b-sides, soundcheck recordings and an entire 1969 performance held at New York’s Madison Square Garden. There is also “Orange Country Suite”—a new tune featuring a recently recorded instrumental backing track to a Jim Morrison demo dating from 1970. But perhaps the most surprising aspect of the set is that only the last disc of the four, entitled “Band Favorites,” includes any previously released material. Clearly, this is no ordinary greatest-hits collection.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

“Everyone in the band had different ideas of what to put on the fourth CD, so we arrived at the idea that each of us would be allowed to pick our five favorite songs,” says Krieger. “We didn’t want to create a ‘best of,’ because that had already been done.

But it is no surprise that Krieger and company placed a premium on crafting such a unique product; the Doors were always true originals. Though their first album arrived in 1967, during the heyday of flower power, the band’s music was dark and apocalyptic. While the Beatles chanted “all you need is love,” Morrison fantasized about killing his father and fucking his mother

The Doors were full of contradictions and riddles. They were a rock trio with a jazz drummer and no bass player (Ray Manzarek filled in the bottom by playing murky, hypnotic ostinatos on the Fender Rhodes keyboard bass he placed on top of his organ). Lead singer Morrison was both a strikingly handsome teen pin-up type and a deeply tormented alcoholic who died at the age of 27. And then there was Krieger.

Krieger joined the Doors in 1965, when he was only 18. At the time, the sum total of his experience on electric guitar was six months. His only real background was in flamenco guitar—two years—for which he used a nylon-stringed instrument. As a result, he played his Gibson guitars with his fingers, producing a spidery, sensuous tone that is unique in the annals of rock.

“I brought Robby to the band,” says drummer John Densmore, still displaying pride in his discovery 32 years later. “I wanted him in because he was my best friend and could play some cool leads. Little did I know that he had this phenomenal melodic sense and innate understanding of song structure. It’s impossible to imagine where we would have been without him. He wrote perfect melodies for Jim to sing: Jim couldn’t have written them more appropriately himself.”

Krieger not only collaborated with Morrison on countless tunes but also penned on his own many of the Doors’ best songs and biggest hits, including “Light My Fire,” “Touch Me” and “Love Me Two Times.”

“Robby’s playing in the Doors displayed as much passion as anyone ever has,” adds Bruce Botnick, the band’s longtime engineer who co-produced the box set with Krieger, Densmore and Manzarek. Botnick joined the project after the death of Doors producer Paul Rothchild, who had catalogued over 40 hours of the band’s music. “That struck me all over again as I went through the archives. There were many nights when he just transcended himself, went inside and rose to extraordinary levels of inspiration.”

Late last summer, just days after the band members recorded “Orange County Suite,” Krieger sat down to go through the four discs of the box set song by song. His assessments are— in the finest tradition of the Doors themselves— insightful and brutally honest.

GUITAR WORLD The box set starts with one of the most controversial moments of your career—the Doors’ performance of “Five to One” at Miami’s Dinner Key Auditorium, in 1969, during which Jim allegedly exposed himself, leading to his arrest and ultimate conviction of indecent exposure. Why did you want to start there?

ROBBY KRIEGER It’s a very revealing track. It shows you where Jim was at the time, and where the band was as well. It’s a very visual track—you can listen to it and imagine what’s going on. The quality, of course, is pretty bad, but it is way better than the bootlegs which have long been out there. Besides, we figured that the poor sound quality is offset by the content.

That was truly a crazy night. Jim was very late getting to the show, and by the time he got there, he was pretty drunk. He had just had a big fight with his girlfriend and future wife, Pam. And not only that, but just before leaving Los Angeles, he had seen a performance by this theater group, the Living Theater. They were the first somewhat legitimate stage ensemble to use total nudity. It was very groundbreaking stuff, where the people in the cast would run out in the audience and get everyone involved. They’d rile everyone up and get in their faces. It was pretty cool, and Jim really dug it. He brought all of us to see it. He saw that again just before he left for Miami, and I think he was pretty affected by it; he was getting more into the idea of being very confrontational with the audience.

GW Right before the Doors recorded L.A. Woman you cut the demo of “Hyacinth House” at your home studio. What do you remember about it?

KRIEGER I had a little house in Benedict Canyon, which is near Laurel Canyon, California. Jim and John and a couple of other people came over there one night. We were just fooling around, taping some stuff. I had this pet bobcat at the time…

GW A pet bobcat?

KRIEGER Yeah, yeah. It would mostly stay outside, but sometimes it would come inside. But by that time it was getting real big and kind of dangerous, so I didn’t let people pet it or anything. And that’s where Jim got that line about the lions. And “hyacinths” referred to some hyacinth flowers that were right outside the window. And in that line about the bathroom, Jim was talking about this friend of ours who was there and kept hogging the bathroom all night. Jim wanted to go to the bathroom, and he couldn’t. Finally, the guy got out of the bathroom, and Jim goes, “I see the bathroom is clear.” He wrote the song on the spot, and I think that was how some of the best Doors songs were written.

GW “Who Scared You,” a b-side to “Wishful, Sinful,” has been something of a “lost” Doors song, one I’ve never seen on any bootleg. Yet it’s a great song. What made it pop back into your consciousness?

KRIEGER Actually, I always liked that song, and I don’t know why we never put it out on an album. Maybe it was a little bit dark, but we should have put it on The Soft Parade, which is when we cut it. I’ve always thought that the Doors were lost on that album because of the orchestration, and it became Jim and the big band. “Who Scared You” is one of the few songs that I feel was enhanced, rather than overwhelmed, by the horns. I think it’s up there with “Touch Me” and “Wishful Sinful.” I’m happy to get it out there, really.

GW “Black Train” is a medley of “Crossroads,” “Mystery Train” and “Away in India,” recorded at a 1970 concert in Philadelphia. It sounds pretty cohesive and flowing. Is that something that you guys often played, or was it a one-time jam?

KRIEGER We played it quite a few times for about a year. I always liked that song a lot. There was a bootlegged version from a show in Seattle that I really liked, which we were going to use. But then we found this version, which seemed a little better. That’s another one I’m happy to get out.

GW “Whiskey, Mystics and Men” is a Morrison Hotel outtake.

KRIEGER Right. That’s a very cool track. We overdubbed a bunch of stuff on it when we were doing An American Prayer [the 1978 recording of Densmore, Krieger and Manzarek backing some 1970 Morrison poetry readings], but we never used it for some reason. It’s unusual: Ray played Mellotron, and it had Fritz Ritchmond, the jug player in the Kweskin Jug Band, the great bluegrass mandolinist Jesse McReynolds and some people chanting. Very interesting stuff. That’s another one that probably should have made it onto an album but for some reason never did.

GW The set includes the band’s first five demo tracks, recorded in 1965, before you joined the Doors, including a version of “Moonlight Drive,” which is followed by another take from a year later, with you on it. It’s interesting to hear what your addition meant to the band.

KRIEGER Oh yeah, definitely. It sounds a lot better. [laughs] The truth is, it wasn’t just me, of course. Everybody was playing a lot differently, and a lot better, by that time. You have to realize that when they did those first demos, it wasn’t really a band. It consisted of Ray, Ray’s brothers playing guitar and harmonica, Jim and John, and this lady bass player. And it was just an early demo, the kind every musician has. We just thought fans would find those tracks interesting. What I brought to the band were just some different musical ideas. Ray’s brothers were good musicians, but they were like a surf band. I came from a different place. I had learned flamenco classical guitar, so I played with my fingers. I had the slide thing, and I was into New York urban blues, and maybe helped the band develop its own sound.

But I think what I really added is the writing aspect, which pushed things in a different direction. When I joined the group, those songs on the demo were about all they had. And when I got in with them, Jim and I just started writing a lot. And that’s where most of the material on the first and second albums came from.

GW Did you have a strong impact on Jim’s writing?

KRIEGER Yeah, I really did, actually. Jim and I started hanging out a lot and jamming and writing, but it wasn’t only that. The four of us just started jamming more and doing different things, getting more musically adventurous and unusual. Even on the first album, there are a lot of odd songs, like “Take It As It Comes,” “Light My Fire” and “The End”—stuff that’s very different from surf music and blues. Stuff that made it more musically complex, more interesting.

GW Ray and John are generally regarded as the band’s jazz influences, but some of your material, in particular “Light My Fire,” shows a strong modal jazz influence, reminiscent of Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue period.

KRIEGER I think we all were equally influenced by that. John and I used to listen to jazz all the time, long before we were ever in the Doors. And Ray was into it, too. John actually played with jazz bands in high school and had some friends who were into it heavily and played some very good jazz. Whereas I never played jazz at that time, but I didn’t know how to play guitar very well yet. I had enough trouble playing rock and roll, so I couldn’t worry about playing jazz. [laughs] I knew my limitations as a player, but I always loved the music and was influenced by its ideas.

GW “Rock Is Dead” is probably going to be one of the more talked-about songs on the set.

KRIEGER That was recorded while we were in the studio doing The Soft Parade. We went out to dinner one night, got really drunk, came back and just started jamming. There was a Mellotron in the studio, which we wanted to use and had been trying to figure out what to do with. We were all drunk, and Ray started playing it, just for fun. And it became that jam, through much of which he plays that thing. That weird organ sound goes in and out of tune is the Mellotron.

GW Where did Jim fit in in that kind of spontaneous improvisation?

KRIEGER We would start playing something first; he wouldn’t just start singing. He would react to us, and then we would try to follow him wherever he was going. So that’s usually how it went; first he followed us, then we followed him.

GW As far as his vocal there goes, it could be argued he was right about rock being dead, because so many rock giants did start dying not too long after that.

KRIEGER Yeah, for sure. First Jimi and Janis, then Jim himself. And then rock really was sort of dead. It really seemed that way to me, though I didn’t know for sure that rock was dead until disco started up a few years later. [laughs]

GW Another interesting piece of music is the last track of the first album, “Albinoni,” a symphonic piece tacked onto the end of “Rock Is Dead.” Where did that come from?

KRIEGER That was a piece of music that we all liked a lot. We were gonna use it for The Soft Parade, at the end of the song “The Soft Parade”; I honestly forget why we didn’t. I think we all decided that it was just too heavy or something, but we had gotten a full string section in, and they nailed a really great rendition. Actually, what happened was someone had the idea to do that, and Bruce Botnick’s father was a string contractor, the guy who puts string sections together, so he called all these guys and they came down and made this beautiful piece of music, which we stupidly never used, until now. I added some guitar to it a couple weeks ago, which I think came out real nice, and John added some very cool percussion.

GW Did you do much overdubbing on the rest of the songs?

KRIEGER Oh, a couple of things, but they are almost all overdubs on the live album. I touched up “Blue Sunday,” “Roadhouse Blues” and “The End” just a little bit. It’s basically stuff that was out of tune and easily fixed. These weren’t like major multitrack recordings, so everything is leaked all over each other, and there’s no way to fix that, which is fine. I mean, a live album is a live album. I just couldn’t resist tweaking a few things that were easily accessible.

I love the version of “The End” because it just really hits a mood, but unfortunately the guitar was out of tune for quite a bit of the song. Which happened pretty frequently by the end of the night. We didn’t have tuners, and I didn’t have a guy on the side of the stage getting my guitars ready. And, in any case, I played just one guitar, an SG, for straight playing and another one, a black beauty Les Paul, for slide. I detuned both E strings to D for “The End,” and it would be pretty tough to keep it in tune. I managed to edit out most of the really bad stuff while retaining the great feel.

GW Do you still have your Doors SGs?

KRIEGER No. The first one was actually a Melody Maker, and after that I had several red SGs. They’re all gone now, mostly stolen and a few lost. To be honest, at the time, I didn’t really care. I just got new ones. They were more or less just tools to me. In the studio I used Fender Twin Reverb amps, and I don’t think I have any of them, either. I do still have my Black Beauty, though.

GW Once you decided that you wanted to do a live disc, how did you come to select this particular New York performance?

KRIEGER We thought it would be nice if we could present one show rather than throw together stuff from a whole bunch of different, unrelated shows. We started going through all our live tapes, and it turned out that we had pretty good tapes of the shows from New York which we didn’t use at all on Absolutely Live, or anywhere else. We used stuff from a couple of shows during the same stand at the Felt Forum and structured them to run like one live set.

GW You’ve always said that Absolutely Live, while good, was not representative of the Doors at their best.

KRIEGER Yeah, and, to tell you the truth, I don’t think we ever recorded anything that was, including this live set on the box. But this version of “The End” does come close for me. There’s just some excitement, some of the feeling that caused the hair on the back of your neck to stand up. That’s the kind of thing that’s so hard to capture on a studio record, but possible at a live show. That’s what we looked for here, and we got it on “The End.” I definitely like that version better than the one on the original album, which I always thought was really just a skeleton of how we played it live. I feel that way about almost everything on the first album. We had no studio experience and had to do everything so fast. I also think studios are by nature, limiting. So I’m happy about having more good live stuff come out.

I believe that the performances of “Ship of Fools” are really good, also “Celebration of the Lizard.” I like that a lot. The audience was pretty cool, and Jim was in an especially good mood. You can tell because of the way he talks to the audience beforehand and gets them in the right mood. There’s also a nice version of “Gloria” and an excellent take of “Crawling King Snake,” which could be our definitive version. The guitar solo is very weird. [laughs] In those days, I probably would not have wanted that heard because it’s very off the wall. But now I like it.

GW Playing “off-the-wall” solos in traditional blues formats was one of your trademarks with the Doors. The slide solo on “I’ve Been Down So Long” comes to mind. Was that the result of spontaneous improvisation? Or did you think, Okay, I’m going to play something weird tonight?

KRIEGER It was spontaneous. I would never play weird just to play weird. I did, however, try to approach things a little differently because, at the time, everyone was imitating Chuck Berry, B.B. King or Michael Bloomfield. Of course, I loved those guys; I listened to Bloomfield’s first Butterfield album [The Paul Butterfield Blues Band, 1965] for hours on end, but I wanted to do something different, to establish my own sound.

GW Why do you think you weren’t able to capture more performances of the band at its best?

KRIEGER In those days, unfortunately, they didn’t really have good microphones and great live recording trucks sitting at the backstage door like they do nowadays. And you didn’t have a soundman running a DAT tape of every performance, giving you a great catalog to choose from. When you decided to record, it was really a big undertaking. The reason so much stuff from the Matrix gig [San Francisco, March 10, 1967] has been bootlegged is that they just happened to record everything there. There is some nice music from there, and we used the best on this set [“The Crystal Ship” and “I Can’t See Your Face in My Mind”], but these weren’t necessarily the best performances ever. They just happened to have a tape recorder down there. And thank God for that, I guess.

GW The version of “The Crystal Ship” recorded there is particularly good.

KRIEGER Thanks. I do like that Matrix material, which was recorded shortly after we had done the first album and were playing really well. And we played some of those songs every night, too, and really just kept polishing them.

GW You guys were known for playing very loud in clubs—and John and Ray always blame you.

KRIEGER [laughs] Yeah, I’ll admit that I always thought, The louder the better, especially on heavy guitar songs like “When the Music’s Over.” You have to play at a certain level to get a certain sound, especially in those days; before they had overdrives you had to be at 10 in order to get the speakers vibrating right, to get that breakup happening. John would get so pissed ’cause he would get these big blisters on his hands from playing so loud. [laughs] He was always bugging me to turn down, but I really felt I had to go to that volume to get the sound I wanted, and felt we needed, and also to fill up the room with sound as just a three-piece. But we didn’t just play loud; there was a lot of attention paid to the music fitting together like a puzzle. In large part, that goes back to the jazz influence. There was a lot of listening to the other guys and having that determine what you’d play.

GW Albert King appears on two songs, “Money” and “Rock Me,” recorded at a show in Vancouver, Canada, on June 6, 1970. How did that come about?

KRIEGER Well, he was opening for us, and we asked him if he wanted to sit in. He was real cool about it. And we had a good time. I really enjoyed playing with him because he was one of my guys. I always loved listening to him, and Jim and everybody else really dug him, too. Everyone was excited to have him out there. I played slide and he played lead. He played, you know, Albert King licks.

GW The third disc of the box set, The Future Ain’t What It Used to Be, opens with “Hello to the Cities,” which is a clever splicing of two tracks—one of Ed Sullivan introducing the Doors “doing their latest hit record,” and one of Jim saying hello to what seems like every city in America.

KRIEGER Using the Ed Sullivan intro was Bruce Botnick’s idea, I think. We put that on there as kind of a joke. “Hello to the Cities” was kind of a silly thing that Jim did to put the audiences off guard, to keep them from becoming too comfortable. He’d go, “Hello, Detroit,” which was where we actually were. And they’d scream back. Then he’d go, “Hello, Chicago.” [laughs] And they’d start thinking, What is he talkin’ about? Then he’d go, “Hello, Pittsburgh,” and just keep going. They’d all think he was nuts by the time he’d done a few of those. And so would I. [laughs]

GW “Break on Through” is from the Isle of Wight Festival, August 1970, which was one of your last live performances, and which took place while Jim was going through his legal proceedings.

KRIEGER That was the last taped performance of the Doors, I believe, and certainly the last filmed performance. The movie of that festival was recently re-released, and anyone who’s seen it knows that our performance was kind of mess. Not just our performance, really, but the whole thing, which was really captured in the movie: people breaking down the walls and running in, everyone arguing about money, and just lots of bad vibes. Now, that was the death of rock and roll. [laughs] It really was the end of everything, the source of all bad things about the whole scene, all rolled into one show.

Jim was just in terrible shape. He had just come from court in Miami and had lost another legal battle, and he had to go back right afterward. In fact, three weeks later, he was convicted. We were supposed to go on tour right after the festival but couldn’t do it because he had to go back to Miami. All of that was taking its toll, and he was just fucking zonked. He just stood there and sang, didn’t move a muscle or do anything. Actually, though, all things considered, it’s surprising how good he sounds.

GW “Mental Floss,” recorded at the Aquarius show, is another Jim monolog.

KRIEGER Right. It’s him talking to the audience. I wanted to have that on there to show a little bit of Jim’s humorous side, along with the crazy asshole side that the movie [The Doors] showed, and which everyone seems to know.

GW Do you think awareness of Jim’s sense of humor has been lost over the years?

KRIEGER Oh, yeah. It’s something that’s never even been talked about. It certainly was not even hinted at in the movie, and most of the books don’t allude to it either. But he could be a real funny guy. He definitely was not a mopey kind of a guy with no sense of humor.

GW Then there’s “Adolph Hitler,” another spoken word piece.

KRIEGER There you go. There’s Jim at his funniest.

GW You recently held an online chat where someone asked if Jim had multiple personalities, and…

KRIEGER …I responded, “No, only two. Biggest asshole in the world and greatest guy in the world.” [laughs] That was really true. He could be either, and you never knew which one it was gonna be.

GW “The Soft Parade,” taken from a 1970 performance on PBS, is your only recorded live version of that song, I believe.

KRIEGER That could very well be. For what it was, it was really good. It’s kind of hard to get into playing rock and roll to just a camera, with no audience. Plus, it was like eight in the morning, and we were asleep. But I think it’s good; we played real well.

GW The three of you composed and recorded some new tracks for the song “Orange County Suite.” How did it feel to make music with John and Ray again?

KRIEGER Well, we’ve gotten together before this a few times, like for An American Prayer, and then “Ghost Song” [a new track recorded for the 1995 CD release of An American Prayer]. Playing with those guys feels the same as it always did; it feels good. But, you know, this is not 1968. It’s just that…well, in those days, that was all there was. I didn’t know anything else, and now I do. So that makes it different. But it’s the same as ever in the sense that we definitely haven’t lost any of our ability to play together.

GW The only previously released songs on the set are on the fourth CD, which is comprised of the three surviving Doors’ favorite band tracks. That’s an interesting concept.

KRIEGER Yeah, it is. The thing is, everyone had different ideas of what to put on the fourth CD, so we arrived at the idea that we could each pick five. At first my idea for this CD was to do The Doors’ Wildest Songs, featuring all of the epics: “The End,” “When the Music’s Over,” “The Soft Parade” and a few others. So when it came to choose my five favorites, I figured, Well, I’ll just choose those five wild songs. But they toned me down a little bit. [laughs] I had too many long ones, so John said, “Well, I’d like to pick ‘When the Music’s Over,’ ” which was fine with me. As long as it’s on there, I don’t care who picked it. That’s my favorite guitar solo.

It was really a challenge because the harmony is static. I had to play 56 bars over the same riff, which isn’t easy. It’s a lot easier to play something over an interesting chord progression. But we did that a lot, and that’s the Miles Davis/John Coltane influence again. I mean, Coltrane soloed brilliantly over minimal chord progressions, and I was always trying to play something that sounded like him—just totally out there in terms of tonality. I’d say “When the Music’s Over” is the closest I ever came to nailing it.

GW Let’s talk about the songs you did pick, starting with “L.A. Woman.”

KRIEGER To me, that’s perhaps the quintessential Doors song. The way it came about was fantastic. We started playing, Jim began coming up with those words, and it just poured forth. I don’t know how he created that whole concept on the spot like that, but he did. You would think that would have been a poem or something that he had written before, but it’s not. That was just written on the spot. I remember Jim sitting in the bathroom singing, and all of us playing together and just having a great

The whole album was, really. We were pretty far down. We couldn’t play anywhere because of the fallout from the indecent exposure; Morrison Hotel hadn’t done that well, and people were saying we were over; Jim looked bad and was getting fat; our longtime producer walked out on us. [Rothchild quit early in the L.A. Woman sessions and Botnick, his engineer, stepped up to co-produce with the band.—Ed.] So, all things considered, I thought it was really cool that the album came out so well and did so well. I think we produced something so loose because there was no pressure. We figured we were screwed, so we started having fun again. We were so far gone that it was like a weight was lifted.

GW Your next selection, “Light My Fire,” was, remarkably, the first song you ever wrote. Ray told me that your songwriting ability was completely unknown to your bandmates, and a wonderful surprise.

KRIEGER I know. [laughs] But look, I didn’t know I could write like that, so how could they? And I don’t know that I ever would have written any songs, much less something like “Light My Fire,” had I never been in the Doors.

When I first started writing songs, I figured I’d write about earth, air, fire or water in order to keep with a concept Jim had of writing about universal subjects, things that wouldn’t go out of style in a week. How much more solid can you get, I figured, than the four elements? Musically, I was trying to get a “Hey, Joe” kind of feel for the chord structure. I didn’t want it to be a blues. I wanted it to be folk rock, more or less.

GW A lot of your writing seems influenced by folk music.

KRIEGER Yeah, I think that is correct. Ironically, I became exposed to a lot of my influences via some albums that Paul Rothchild had produced for Elektra. They were New York urban blues albums by guys like Geoff Muldaur, Danny Kalb, and Koerner, Ray and Glover, all guys who had drifted in New York’s Greenwich Village in the early Sixties and put out these white urban folk blues albums on Elektra. I loved that stuff. In fact, the musical idea for “Love Me Two Times” came from a Danny Kalb lick.

GW Well, you put both your folky and jazz influences to spectacular use on “Light My Fire.” Without that song the Doors’ entire career would have been vastly different. I think you might have been like the Velvet Underground, a great band that became popular only years after their recording heyday.

KRIEGER It’s impossible to say for sure, but having that Top 40 hit definitely puts you in a whole different ball game. Somehow though, despite having Top 10 hits, the Doors still tended to be thought of as an underground band.

You know, I don’t even know if we would have ever recorded all our albums if “Light My Fire” hadn’t hit, because our first single, “Break on Through,” didn’t really do much and several months went by before they edited “Light My Fire” [the single version, from which much of Krieger’s memorable guitar solo was edited—Ed.] and put it out. The album was starting to look like a failure, and who knows whether Elektra would’ve even picked up our option after two albums if we haven’t had some sales success.

GW Getting back to your five selections for the fourth CD, what about “Peace Frog”?

KRIEGER Well, I had written the music to that without any lyrics. I kind of messed up on it, but it came out sounding really cool. Jim couldn’t figure out words for it, and I didn’t have any, so we just cut it as an instrumental track. Later, he got out his notebook, and he and Rothchild found this poem that seemed to work with it. And that’s how that came about. That was extremely unusual, because usually we wouldn’t record something until he knew what he was going to sing on it. And the lyrics usually came with the music, not in two separate packages.

GW “Take It As It Comes” is next.

KRIEGER That was a favorite saying of the Maharishi [Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, teacher of transcendental meditation—Ed.]. Most people I know think I wrote that song, but I didn’t. I wrote the music, but Jim wrote the words. And he knew nothing about meditation, either. Kind of weird.

But, actually, what makes it one of my favorites is the music. I was trying to stay away from a Chuck Berry sound and come up with something that was not blues, not folk rock, but just the Doors, identifiably ours. And, looking back, I think we succeeded at this tremendously on this song.

GW The last one is “Wishful Sinful.”

KRIEGER Again, that’s one of the only songs from The Soft Parade where I really think the orchestra actually added something to the song that wasn’t there to begin with. Getting back to the elements idea, this was a water song.

GW The Doors still seem to resonate with young music fans. How do you account for this?

KRIEGER I get asked that a lot, and I wish I had some snappy answer, but I don’t. I think it’s that they hear a certain honesty in the music, and in Jim’s voice, which is just not there in today’s music, because it’s gotten to be such a business. Money rules the music industry now. It may have always ruled the executives, but not the musicians. And that’s changed, I’m afraid; it’s just gotten so commercialized. I think people realize that the Doors were not about that. They hear it in the music, and they like it.

But it is amazing how many young kids, even 10-year-olds, are into the Doors. And it’s not always because of their parents either. They hear us on the radio, or their friends have our CDs, or they read one of those books about the band. Then they get obsessed. It’s really amazing, and it just doesn’t seem to slow down, which is great.

GW Great for you.

KRIEGER Yeah. [laughs] Great for me.

Alan Paul is the author of four books, including Brothers and Sisters: The Allman Brothers Band and the Inside Story of the Album That Defined '70s as well as Texas Flood: The Inside Story of Stevie Ray Vaughan and One Way Out: The Inside Story of the Allman Brothers Band – both of which were both New York Times bestsellers – and Big in China: My Unlikely Adventures Raising a Family, Playing the Blues and Becoming a Star in Beijing, a memoir about raising a family in Beijing and forming a Chinese blues band that toured the nation. He’s been associated with Guitar World for 30 years, serving as managing editor from 1991 to 1996. He plays in two bands: Big in China and Friends of the Brothers (with Guitar World’s Andy Aledort).