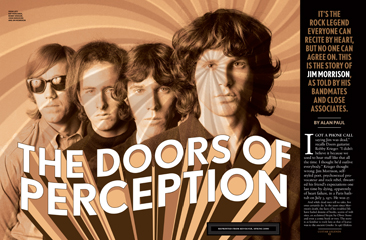

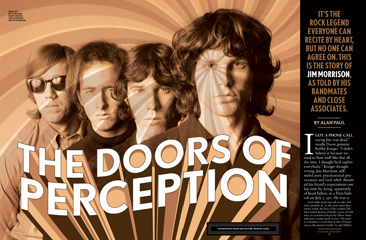

The Doors: The Doors of Perception

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It’s the rock legend everyone can recite by heart, but no one can agree on. This is the story of Jim Morrison, as told by his bandmates and close associates.

I got a phone call saying Jim was dead,” recalls Doors guitarist Robby Krieger. “I didn’t believe it because we used to hear stuff like that all the time. I thought he’d outlive everybody.” Krieger thought wrong: Jim Morrison, self-styled poet, psychosexual provocateur and rock rebel, thwarted his friend’s expectations one last time by dying, apparently of heart failure, in a Paris bathtub on July 3, 1971. He was 27.

And while dead men tell no tales, live ones certainly do. In the years since Morrison’s death, the facts of his troubled life have fueled dozens of books, scores of web sites, an acclaimed biopic by Oliver Stone and even a comic book or two. The story is as familiar to rock fans as that of Icarus was to the ancient Greeks: In 1967 Elektra released the debut album by the Doors, a Los Angeles quartet. Fronted by former UCLA film student Jim Morrison, the band challenged good vibrations of the prevalent hippie culture with brooding, trance-inducing songs that celebrated madness, chaos and fucking your mother. It’s a stance for which they have never made any apologies, societal disapproval notwithstanding.

“To deny the darkness of the soul is to be but half a human being,” says keyboardist Ray Manzarek. “But we had both sides. The Doors were a balancing act between the light and the dark. I mean, the solos in ‘Light My Fire’ are as joyous as life gets.”

In fact, it was the hit single “Light My Fire” that catapulted the band into the limelight and helped the Doors become one of the biggest—and certainly most unexpected— hits of 1967, demonstrating that a band could be dark, weird and commercially successful.

From there, the Doors entered an exhaustingly accelerated life cycle, touring endlessly while also managing to record five more studio albums in just four years. But as the band’s popularity grew, Morrison himself began to disintegrate, mutating from pin-up visionary to dissolute, overweight rock star. The singer hit rock-bottom on March 1, 1969, when he was arrested for allegedly screaming obscenities and committing indecent exposure while onstage in Miami. After the bust, Morrison recorded two more albums with the Doors, then fled to Paris for some “rest and relaxation.” He never returned.

The story may be familiar, but the more the yarn is told, the taller the tales grow. Some more exotic accounts, for example, have Jim faking his death and escaping to the Bahamas, where he currently tends bar.

All the latest guitar news, interviews, lessons, reviews, deals and more, direct to your inbox!

With the recent release of a newly remastered Doors box set and a star-studded Doors tribute album near completion, the time was right to try and set the record straight. To do so, we spoke with those who knew Jim best: the three surviving members of the Doors— Manzarek, Krieger and drummer John Densmore— as well as Danny Sugerman, who began his association with the band as a teenaged errand boy and ended up as their manager, and engineer/producer Bruce Botnick, who was in the studio for every Doors session.

Using the band’s studio releases as reference points, each bandmember gives his version of the rise and fall of Jim Morrison and the Doors. Manzarek provides the myth and magic, Krieger contributes the musical insight and dispassionate remembrances, and the clear-eyed Densmore offers the healthy dash of reality. Botnick and Sugerman add detail and perspective. While individual recollections occasionally clash, together the group provides the closest picture of the truth currently available.

Unless, that is, Jim decides to put down his piña colada and gives us a call. Hey, you never know.

*****

RAY MANZAREK Jim and I graduated from UCLA Film School in 1965, him with a Bachelor’s and me with a Master’s. He said he was moving to New York, and I thought I’d never see him again. Forty days and 40 nights later, almost biblically, I’m sitting on Venice Beach in the middle of the day, thinking, What am I going to do with myself ? And Jim Morrison comes walking along the edge of the water, backlit by the sun, diamonds coming off his feet. He’s like Krishna, like the new blue God. He was wearing just cutoffs and his hair had grown out, and he was beginning to look like Michelangelo’s David. I waved and yelled to him.

He came over and said, “What are you up to?” I said, “I’m not up to shit, man. How about you?” And he goes, “I’ve been writing songs.” My antenna perked up and I said, “Sit down and sing me one.” He was very shy and had a very soft, Chet Baker–like voice. The first song he sang was “Moonlight Drive,” and the moment I heard the lyrics—“Let’s swim to the moon, let’s climb through the tide, penetrate the evening that the city sleeps to hide”—I thought, Wow, man. Psychedelic. Because those words were LSD, and we were both acid heads. I’m imagining all the things I could do behind him—a little jazz, good, strong backbeats, some Ray Charles vamps—and I’m thinking, Jesus, this is amazing. We are going to form a rock band and be great. Because who was the competition? The Beatles playing Everly Brothers and the Rolling Stones doing Chicago blues. This was a whole different thing, a whole new genre.

I said to Jim, “This is going to be psychedelic. But there’s only one problem: what do we call it?” And he goes, “I already got the name, man. The Doors.” I said, “The Doors? That’s ridic… Oh, like the doors of perception? The doors of your mind?” And he said, “Exactly. Open the doors of perception.” I said, “That’s it, man. That’s it.”

JOHN DENSMORE Ray was in my meditation class, but we didn’t really know each other. He came up to me and said, “I hear you play drums. I have a great singer and I need a drummer.”

MANZAREK John and I were big Coltrane and Miles Davis fans, and we really tried to bring a lot of their modal influence to rock. I said to him, “I want to bring jazz elements into this band.” And he goes, “Oh man, what you’re talking about has never been done. It’s like jazz-rock.” I said, “There you go, man. Jazz-rock. That’s exactly what I want to do.”

DENSMORE It was exciting to think about doing something new. We had the same heroes and inspirations, and it seemed possible that we could create something really creative and inspirational. But as much as Ray likes to say that he founded the Doors with Jim and all that, it’s all bull to me, because the Doors did not exist until we hooked up with Robby Krieger—until I brought him to the band, thank you very much. His melodic sense and understanding of song structure were extremely deep. Without him, I can’t imagine what the Doors would have become.

I’ve known Robby since high school and he’s always been the same. He’s a great guy and a great musician, but he seems kind of out of it. And it’s not due to substance abuse. He’s just thinking about other stuff rather than the practical. I once said to Robby, “I love your solos, but you look like you’re lost! What are you thinking about?” And he said, “Oh, a fish in my fish tank.” So, he’s elusive, but he’s not dumb, believe me. He’s a very smart guy.

MANZAREK We originally had my brother Jim on harp and my brother Rick on guitar. We had some rehearsals and cut a demo, but it was going nowhere, we had no gigs, and my brothers both said, “Nothing is happening here. We have other things to do with our lives.” Then John said, “I know a great guitar player: Robby Krieger. He’s in our meditation class.”

ROBBY KRIEGER Ray’s brothers were good musicians, but they were like a surf band. I was coming from a different place. I had learned flamenco classical guitar, so I played with my fingers. I played slide, and I was into urban blues, all of which helped the band develop its own sound. But I think the writing aspect is what I really added. Jim and I just started writing a lot right away. And that’s where most of the material on the first and second albums came from. But that was all unknown to everyone when they hired me. They liked me because of my slide playing.

MANZAREK The first time we got together with Robby was at a friend’s house in Venice Beach. We started playing “Moonlight Drive,” and Robby said, “I’ve got something that might fit this.” He opens that little center thing on his guitar case, where you keep your strings, picks and stash, and out comes this jagged glass bottleneck. I thought, Why does he have a fucking weapon in there? What kind of gigs does this guy play?

I said, “God, man, what are you gonna do with that?” He said, “Fool, this is a bottleneck! Here’s what you do with it.” And he slipped it on and played that glass against the steel strings, and Morrison and I just shivered. It was one of the eeriest, spookiest sounds I had ever heard. Jim said, “That’s our sound, man! I want that on every single song.” Bam, that was it. We all smoked a joint and something magical happened. Robby was our secret weapon.

KRIEGER I first met Jim when he came to my house with John Densmore; he seemed pretty normal. I didn’t really get a sense that there was anything unusual about him until the end of our first rehearsal. Initially, everything was cool. Then this guy came by. Something had gone wrong with a dope deal, and Jim just went nuts. Absolutely bananas. I thought, Jesus Christ, this guy’s not normal.

DENSMORE One night, Jim asked me to take him to this girl Rosanna’s apartment in Beverly Hills. This attractive blonde let him in, surprised he was there. We went in and sat down at the kitchen table, and Jim started rolling joints, acting like he lived there. “Help yourself, Jim,” she said sarcastically. I felt claustrophobic from the mounting tension, so I said I’d be back in a little while and split.

When I came back, the door opened as I knocked, so I walked in and saw Jim holding a large kitchen knife to Rosanna’s stomach. A couple of buttons on her blouse popped as Jim twisted her arm behind her back. My pulse tripled, and I went, “What do we have here?” trying to defuse the situation. Jim looked at me with surprise and let Rosanna go. “Just having a little fun.” Jim put the knife down and Rosanna’s expression changed from fear and rage to relief. I asked him if he wanted a ride home, and when he said no, I made a quick retreat. At the time, I rationalized leaving that girl in a potentially dangerous situation with Jim by thinking that there was definitely sexual tension in the room as well as violent tension. But to be honest, I was worried about myself; I couldn’t tell anyone that I was in a band with a psychotic because if they said I should quit, I would have no options. The Doors was my only ticket out of my family and into a career I loved and wanted so badly.

MANZAREK After Robby joined, we spent about six months rehearsing, and then our first real gig was as the house band at the London Fog on Sunset Strip. We’d go look longingly into the window of the Whisky. And within three months, by June ’66, we were the house band there. We played there through summer and got fired in late August for playing “The End.”

It was the first time Jim ever recited the oedipal section: “The killer awoke before dawn…” Even we had never heard it before. He minced words on the record, but certainly not in person. It was, “Father, I want to kill you. Mother, I want to fuck you.” I knew it was going to get us in trouble, but I thought it was brilliant. He was doing a dream interpretation of the classic Freudian Oedipus complex that was so talked about in the early Sixties.

KRIEGER We were all kind of freaked out recording the first album, because we didn’t know what it would be like. We didn’t understand the studio process, so, for example, it really bothered us that we couldn’t turn up as loud as we wanted. But we had been playing those songs for so long that we really had the material down cold. Everything was cut in one or two takes.

DENSMORE We recorded the first album in 10 days or so because we really knew the songs, almost all of which were written just after Robby joined.

KRIEGER While we were recording “The End,” our engineer, Bruce Botnick, had brought a TV into the studio to watch the World Series. Jim, who was on a lot of acid, got kind of pissed off because baseball wasn’t exactly conducive to setting the right mood for “The End,” so he threw the damn thing through the control room window. That got everyone’s attention.

BRUCE BOTNICK I’ll tell you one thing: Jim did not throw my TV through the control room window. He knocked it over, and I really believe even that was an accident. I still have the little TV, so I know. Everyone remembers this great big scene, but it did not happen. If the control room window had been shattered, I would know, believe me. It would have stopped the session dead in its tracks.

KRIEGER I also remember Jim sitting at the table out in the snack bar area ranting on and on, “Fuck the mother, kill the father. That’s where it’s at, man. Fuck the mother, kill the father.” And we’re going, “Yeah, right, Jim, but we’ve got to record. How about singing?” We finally got him into the studio for two takes and we nailed it—the vocal is actually Jim’s live take, which is pretty unusual for us. And then we thanked God, because considering Jim’s state of mind, we knew we weren’t going to have too many cracks at it.

*****

KRIEGER We recorded our second album less than a year after our first, but we were ready. We had tons of material and were anxious to record.

MANZAREK God, it’s incredible to look back upon how much we did so fast. And it’s not as if we were under some kind of insane pressure. We were just doing our thing, but the entire society was operating at a furious clip. War was going on, man. People were dying. Young American men were dying and getting maimed thousands of miles away in Vietnam, a country about which we knew nothing. There was a horror loose on the planet. Consequently, we had an intense visitation of energy in those years. So nothing seemed out of the ordinary.

It was so much more of an exciting time; everything was a matter of life and death. Now it’s a matter of slow suffocation and eventual capitulation to the powers that be. A slow putting on of the yoke.

KRIEGER One night while recording Strange Days, we were getting ready to leave for the night. Jim, who didn’t want to stop because he was feeling good, kept saying, “Man, I want to play all night.” But we were all tired and wanted to go home. Jim finally left, but he came back half an hour later, climbed over the fence, broke into the studio, took out the fire extinguisher and sprayed it into the piano and all over everything. It was quite a surprise in the morning.

DENSMORE We knew all the groups in the San Fran scene—the clique of the Dead, the Airplane and Quicksilver Messenger Service— but we were odd men out. We didn’t fit in anywhere. We were in the L.A. scene but we were always different there, too. It was more peace and love than we ever were.

KRIEGER We never got too close with the San Francisco groups—especially the Dead, who wouldn’t let us use their amps one night. We had a gig at Beverly Hills High one afternoon and another in Santa Barbara that night, so we left our gear, figuring the Dead would let us use their stuff. You’d always let people use your amps in those days, but they just refused.

MANZAREK We didn’t have the California sound. We were neither a surfer band nor a folk-rock band with close harmony. There wasn’t any country and western in it. It was big-city music, based in black roots rather than white. And it’s pretty white out here in California. This is a much whiter part of the country than most people realize.

DENSMORE Robby and I always talked about Jim’s darkness, which we caught on to early on, though Ray says he didn’t sense it. I was always thinking, like, Oh, shit. Love just replaced their drummer and I’m better than the new guy. Damn, if I was only in that band there wouldn’t be this pressure, this strain of always wondering what’s going to happen with Morrison being so wild and out there.

KRIEGER It was hard living with Jim. It would have been so great if we’d just had a guy like Sting—a normal guy who’s extremely talented, too. Someone who didn’t have to be on the verge of life and death every second.

DENSMORE I don’t think Jim ever missed a gig. Several times he was so wrecked that it was terrible, but for such a wild guy it’s pretty amazing that he made the gigs and was always able to pull himself together to make great records.

KRIEGER The music was all Jim lived for. Often, he was at the office when we weren’t. He even lived there sometimes, because that was his whole life. We all had lives outside the Doors, but he didn’t, and he kind of resented that. He felt like he was living it 24 hours a day, and we weren’t. And he was right.

Still, the recording sessions really bored him. We had to hang around interminably until they got the drum sound down and all that shit, so I can’t blame him for going nuts. Paul Rothchild, our producer, was a real perfectionist. And things got really bad by our third album. We had no more material and Jim was pretty fucked up on liquor by then, so it was hard to write with him. That’s when I started writing more of my own songs.

*****

MANZAREKWaiting for the Sun was a low point. Jim had really hit the bottle and was firmly in the grips of alcoholism, although we didn’t understand it at the time. Not that Jim hadn’t been drinking before, but this was taken to a whole new level. This was no longer a young man’s drinking. It was a full man’s alcohol abuse.

KRIEGER That’s when the liquor really started being a problem. Before that, everything was more or less fine. LSD was no problem because it was a creative thing. There’s nothing good about liquor—it just fucks you up—though at first it relaxes you, which is what you probably need after taking eight zillion acid trips.

And Jim was being taken advantage of by hangers-on. He would bring them to the studio and Rothchild would go bonkers—all these drunken assholes would be hanging around, fucking in the echo chamber and pissing in the closets. It was a mess. Jim would drink with anybody because we wouldn’t drink with him. He would take on all these assholes who used him: “Hey, we’re hanging with Jimbo.” And they wouldn’t care how fucked up he got—they’d leave him on somebody’s doorstep in his own puke. I actually never drank with him because I didn’t like to drink to excess and he loved to go until he couldn’t see. I knew what was coming and hated to see it, so I would usually be gone by that point. John and Ray felt the same way. And for all of us the romance of drugs was definitely gone by then because of what we were seeing in front of our faces.

MANZAREK There were a lot of days during those sessions where we said, “Jim’s unable to do anything.” There started being periods where we didn’t see him for five days or a week. Then he’d show up and go, “Oay, let’s get back to work.”

KRIEGER We were getting depressed about the whole situation, so it helped that “Hello, I Love You” and Waiting for the Sun were Number One hits. That really buoyed our spirits.

*****

MANZAREK We had done three albums featuring the Doors in their truest and purest essence. It was time to feature the Doors with augmentation. That was the whole idea behind using an orchestra and horn section on The Soft Parade.

KRIEGER I was skeptical. I thought that the Doors would be lost, that it would just become “Jim and the big band.” I was wrong, and I didn’t realize it until I first heard “Touch Me” booming through the big studio speakers. Until that point, I really thought it was just a keep-up-with-the-Joneses thing: the Beatles made Sgt. Pepper’s, and suddenly everyone had to record with strings and horns. I didn’t see any need for us to follow along.

All I remember are endless mixing sessions. That was a very long, drawnout album. We spent more money on it than we did on any other album. And Jim was hard to find. All the mixing bored the hell out of him.

BOTNICK In a way, it’s a miracle the record got completed at all. And it’s interesting that even in turbulent times the band was looking to experiment and grow. An artist has to do that or else he becomes very boring. You become a machine and start to manufacture yourself, which is not what the Doors were doing.

MANZAREK I think the album fits right in there with our other ones. It’s just the Doors with horns and strings, man. I always hated the notion that we were just a dark, spooky band. Soft Parade was proof that we could do other things, too. The horns were not spooky, but the song “The Soft Parade,” which was composed of five suites strung together behind Jim’s poetry, was. If we didn’t balance the dark with the light, we would have been fools. And we were not fools.

KRIEGER During the sessions, this crazed guy, who apparently thought that “The Celebration of the Lizard” [a Morrison poem which appeared on Waiting for the Sun] was written about him, appeared. He yelled, “How did you know that I’m the Lizard King, goddamn it! That’s me. You wrote a song about me!” And he smacked Ray right in the eye because he thought Ray was Jim. Ray had his glasses on and they just crumpled. It was a mess.

Jim was always obsessed with lizards because he’d seen them a lot when he was on acid. But I don’t know when he came up with “I am the Lizard King.” I think he wished he had never said that. It was just another thing he had to live up to.

DENSMORE “Touch Me” was a hit and we went back on the road. Then [on March 1], we played Miami and all hell broke loose. But we didn’t realize that it was really the beginning of the end.

MANZAREK It was certainly an out-ofcontrol night, but the eventual problems were caused by the accusation that Jim had exposed himself. Did he do so? We’ll never know for sure, because we never actually asked him. We operated on a subtle psychic level rather than a gross one. That may be hard to understand today because there is no longer such a thing as a subtle level, but there was in the Sixties, and for us to ask a direct question would have violated that connection and ruined it forever. It would have made us like the military, the cops, or an attorney. To ask such a direct question would have made us The Man: “Jim, did you expose your penis?”

Besides, it was obvious to me that he had not done so. We assumed he didn’t, but that his ruse had worked on the people. He said, “Do you want to see my cock? I’m gonna show it to you. I’m gonna show you my penis!” Then he pulled his shirt back and forth. It was obvious to me that he wasn’t pulling his dick out, man. He was feeling the weight of their expectations, knowing that they were coming to see a freak show, so he put on a snake-oil carnival show and they all fell for it. Two hundred photos were eventually entered as evidence at the subsequent trial, but not one contained even a glimpse of the “ivory shaft.” What, all of a sudden everyone was so awed that they stopped taking pictures?

DENSMORE In the studio Jim could really deliver, and if he was in terrible shape, we could scrap his track or skip a session. But there was no control live, so I always had a sense of dread, a knowledge that anything could happen. We were so good live, then we weren’t so good, and you never knew which band would show up, because you never knew which Jim would show up.

KRIEGER I never saw him pull it out—I still don’t think he really did—but it was truly a crazy night. Jim was very late, and by the time he got there, was pretty drunk. He had just had a big fight with his girlfriend, Pam. Not only that, but just before leaving Los Angeles, he had seen a performance by the Living Theater. They were the first somewhat legitimate theater group to use total nudity. It was very groundbreaking stuff, where the people in the cast would run out in the audience and get everyone involved. They’d rile everyone up and get in their faces. Jim really dug it—he brought all of us to see it—and I think he was pretty affected by it; he was getting more into the idea of being confrontational with the audience. All of those conditions came together to cause what happened at the show.

We were usually good at maintaining the music through even the most intense craziness. That was what we did. But let’s be honest; it did fall apart in Miami. Usually, we were at least able to make it through the show, no matter what, but Miami only lasted two or three songs after “Five to One.” It was bedlam, just total craziness. The place was incredibly oversold and sweltering hot, thousands of people swarmed the stage, and it collapsed. I remember Jim just rolling around in the midst of all these people and wondering if we would ever get out of there. The last thing I remember was Jim out in the audience, leading this huge snaking line of people. And us all running for the rafters.

DENSMORE It was very wild, but we had no idea what it would lead to. The whole country was very polarized, and some people were very scared by the changes they saw. And we became their rallying cry. Suddenly, 30,000 homophobes led by Anita Bryant and Jackie Gleason were rallying in the Orange Bowl against the Doors.

KRIEGER Nothing happened until a week after the concert, when somebody decided to make a stink about it. No one seemed to be angry at the show, nobody asked for their money back. And the cops were friendly— they sat around drinking beers with us. But then some politician decided to make his career at our expense, and it fucked everything up. We were banned by the Concert Hall Manager’s Association, and we basically couldn’t play anywhere for a year. It was never quite the same again.

MANZAREK Jim was eventually convicted— sentenced to hard labor, man—but he stayed free while he appealed. I was shocked when I heard about the charge of simulation of oral copulation. I couldn’t figure out where that came from until I saw the picture of Jim on his knees in front of Robby during a guitar solo. He was on his hands and knees, egging on Robby and his guitar, but the charge was a joke, man. As for the other charges: being drunk in public? Guilty. Using profanity? Guilty.

MANZAREK During the sessions for Morrison Hotel, Jim was on trial in Miami and we couldn’t get gigs anywhere, which obviously affected the mood. Another factor in making that album was that everyone had knocked us for overproducing The Soft Parade, so we kind of wanted to get back to the basics.

KRIEGER “Roadhouse Blues” is one of my personal favorites. I was always proud of that song because, as simple as it is, it’s not just another blues. That one little lick makes it a song, and I think that sums up the genius of the Doors. I think that song stands up really well as an example of what made us a great band. And the session was really cool— one of my fondest memories of the band. We cut the tune live, with John Sebastian playing harp and Lonnie Mack playing bass.

DENSMORE As soon as we could we went back on the road, which I didn’t really want to do. I begged them to get off the road for a year because of Jim’s deterioration, which I think, unfortunately, weighed heaviest on me. Robby, who just loved to play music, somehow managed not to look at Jim’s collapse, and Ray wouldn’t look at it at all. We played Dallas, Texas, and it was really good, so I thought, “Wow, maybe we could be more mature, a little jazzier. Maybe we could have a live career again.” But it was an illusion. Jim couldn’t stop. He was past that at this point. The next night we played New Orleans and it was just pathetic. We went home and never played live with Jim again.

DANNY SUGERMAN The three of them decided not to push it any more with Jim, but I think Jim’s desire to play live really diminished as well. People were expecting more and more from him, and I think he resented their expectations that he be this charismatic, unpredictable, wild frontman and, after Miami, to whip it out every night. And I know he resented people expecting to hear “Light My Fire” every night. He thought of himself as an artist and felt that the audience was not getting it. What he lived for was being misinterpreted, so he decided to just completely stop trying to be what his audience expected.

***

KRIEGER At the time of L.A. Woman, the Doors were looking like a doomed thing and I felt like Paul Rothchild was a rat deserting a sinking ship. We couldn’t play anywhere, Morrison Hotel didn’t do that well, Jim looked bad and was getting fat. And I think we came up with something so loose exactly because there was no pressure. We figured we were already screwed, so we were having fun again. All things considered, I thought it was pretty cool that L.A. Woman did well.

BOTNICK We went back into the studio and very early Paul turned to me and said, “I just can’t do this again. I’m not getting off on it anymore.” He didn’t have the strength to get it up again. There were times when the albums wouldn’t have gotten done if Paul hadn’t been there as the controlling ringmaster, but, as a result, it became the norm for him to be in control, rather than backing off and allowing the albums to evolve naturally. He realized that they were tired of it. They couldn’t get it up again, either. They had been through a lot and wanted to get in and out and have some fun, to do things in a more relaxed manner. So I rented a bunch of equipment and brought it to the Doors’ Workshop, their rehearsal space, where they were comfortable, and we rolled tape.

KRIEGER The warden was gone. We just kind of took it for granted that Paul would produce and we would do things his way—that you should stick with a successful formula. He was very important to a lot of the albums, but it just wasn’t going to work again.

BOTNICK Making L.A. Woman was a very, very nice experience. As soon as Paul was gone, Jim was totally different. He was on great behavior—on time every day, not drinking—and having a lot of fun, because the father figure wasn’t there. That sort of rebellion was a reflex action for him. His father was an admiral in the Navy and everything was, “Yes sir, no sir,” and I think that all his rebellion was a lashing out at that. With Paul removed, none of the demons that had taken him over during the other recordings were present.

DENSMORE Whenever someone became an authority figure, Jim rebelled. It happened with Ray. He lived with Ray and [Ray’s wife] Dorothy in the early days and they were very close. Then Ray told him to get a haircut or something and Jim went nuts and trashed their house.

KRIEGER Jim was almost like Ray and Dorothy’s son. Then he rebelled and fucked their house up—trashed it on more than one occasion. He took advantage of them in many ways.

MANZAREK It felt great to have success with “Love Her Madly,” which was a big AM hit, and “L.A. Woman” and “Riders on the Storm,” which were big FM hits. And it seemed appropriate, because recording the album was terrific. We knocked that baby out in a week. We had Jerry Scheff, Elvis’ bass player, and Marc Benno playing guitar, which freed up Robby and really cut back on the need to overdub. Two-thirds of the album is recorded live, with Jim singing along in his vocal booth—the bathroom, with its great echo.

SUGERMAN About halfway through mixing the album, Jim said, “It sounds great. You don’t need me.” Jim never really participated in mixing anyhow; he just okayed the final product. He said he was going to take off for a while. He made the rounds saying bye to everyone, really going on benders, although he showed up for work every day in good shape. Everyone understood Jim needed a break and was anxious for him to take it. The thought was Jim would go to Paris and have a vacation, which he hadn’t had in four years, that he would take off as much time as he needed and come back refreshed and ready to tour.

MANZAREK Jim went to Paris for rest and recuperation. He was going to be a poet and an artist. He had left rock and roll to take an artistic break from being an icon, and we were all very excited about that.

DENSMORE Ray says Jim was going over to chill out, but I wasn’t convinced. I mean, the Parisians drink vino for breakfast, and I was kind of worried that he would take up that French tradition—which, in fact, he did. Ray wrote in his book that I called Jim up and begged him to come back, and he told me to fuck off. Absolutely false! What happened is Jim called me from Paris and asked about L.A. Woman. I told him it was doing great and he said, “Great. We can do another record.” And I was thinking, I don’t know, man. You still sound kind of fucked up. He was slurring his words and was clearly a little loaded. He just was not in good shape, so I wasn’t counting my chickens.

SUGERMAN Jim certainly spent a lot of time in Paris getting drunk and writing poetry. He really developed into a great poet and wrote a lot during that time, but it didn’t impinge on his drinking. Looking back, it seems obvious that he was self-destructing in front of our eyes—he had aged unbelievably in four years—but I didn’t see it. I naively thought he would lose weight and shave and get back to normal.

MANZAREK The fact that he died over there came as a complete shock. He didn’t die hanging around with the sleazeball buddies in the Santa Monica Mafia. He was in Paris with Pam, getting away from all that, and he died, man. So it was a terrible shock. But on the other hand, knowing how much he had drunk, we all went, “Christ, it finally killed him.”

DENSMORE There was talk from the very beginning that Jim faked his death. He was a real wild guy, and he was so smart that he could have thought up a scheme like that. But it didn’t happen, and the thing that bugs me is Ray waxed on the idea for years to build myths and sell records. But I can’t get mad, really, because I think Ray was incredibly hurt by Jim’s checking out and unable to adequately express it.